Vương quốc Phù Nam

Cho đến đầu buổi bình minh của thế kỷ 20, mới có sự thông báo về vương quốc Hindu cổ này trong vài văn bản chữ Hán. Vương quốc cổ nầy được đề cập lần đầu tiên vào thời Tam Quốc (220-265) qua một văn bản chữ Hán vào lúc có sự thiết lập quan hệ ngoại giao của nhà Đông Ngô với các nước ngoại bang. Trong báo cáo này, người ta có biên chép rằng thống đốc của hai tỉnh Quãng Đông và Bắc Kỳ tên là Lu-Tai có cử các đại diện (congshi) đến các vùng ở phía nam của nước ông. Các vua ở các vùng nầy trong đó có nước Phù Nam, Lâm Ấp và Tang Ming (một quốc gia được xác định ở phía bắc của Chân Lạp vào thời nhà Đường), cũng có từng gửi một sứ giã đến cống vật cho Lu Tai. Sau đó, nước Phù Nam cũng được nhắc đến trong các biên sử từ nhà Tấn cho đến nhà Đường. Tên Phù Nam đây là phiên âm của từ cổ bhnam (núi) của người Khờ Me trong chữ Hán. Tuy nhiên, điều này cũng tạo ra sự dè dặt và nỗi e ngại của một số chuyên gia về việc giải thích từ « Phù Nam » với từ « núi ». Họ nhận thấy từ Phù Nam theo nghĩa « gò » nó đúng hơn trong sự biện minh bởi vì với thời gian gần đây, trong các cuộc nghiên cứu dân tộc học [Martin 1991; Porée-Maspero 1962-69] người Khờ Me thường có thói quen thực hành các nghi lễ xung quanh các gò nhân tạo. Người Hoa không biết phong tục này nên họ ám chỉ đến cách thức thực hành này để chỉ định vương quốc này. Nhờ các cuộc khai quật khảo cổ bắt đầu vào năm 1944 tại Óc Eo thuộc tỉnh An Giang ở miền nam Việt Nam hiện nay dưới sự hướng dẫn của ông Louis Malleret thì không còn sự nghi ngờ nào nữa về sự tồn tại và thịnh vượng của vương quốc Ấn Độ hóa này. Những kết quả thu thập từ các cuộc khai quật này đã được ghi chép trong luận án tiến sĩ của ông, sau đó còn được công bố trong một cuốn sách có tựa đề là « Khảo cổ học của đồng bằng sông Cửu Long« . Nó bao gồm được 6 tập.

Điều đó mới có thể xác minh được các dữ liệu của người Hoa và càng làm rõ ràng hơn trong việc giới hạn địa phận của vương quốc nầy. Vì tìm ra được rất nhiều các vật khảo cổ bằng thiếc nên nhà khảo cổ Pháp Louis Malleret không ngần ngại dùng tên Óc Eo để chỉ định văn hóa đồ thiếc nầy. Bây giờ mới bắt đầu có một ánh sáng rực rỡ trên vương quốc này cũng như về các mối quan hệ bên ngoài của nó trong quá trình nối lại các chiến dịch khai quật được thực hiện với các é-kip Việt Nam (Đào Linh Côn, Võ Sĩ Khải, Lê Xuân Diêm) cũng như với é-kip Pháp-Việt dưới sự hướng dẫn của Pierre-Yves-Manguin từ năm 1998 đến 2002 trong các tỉnh An Giang, Đồng Tháp và Long An, những nơi mà tìm ra được nhiều di tích của văn hóa Óc Eo. Được biết Óc Eo là một hải cảng quan trọng của vương quốc này và là trung tâm thương mại một mặt giữa bán đảo Mã Lai và Ấn Độ và mặt khác giữa sông Mê Kông và Trung Quốc. Khi những chiếc thuyền của khu vực không thể đi được quãng đường dài và phải đi dọc theo bờ biển, Óc Eo trở thành vì thế một lối đi bắt buộc và cũng là một chặng chiến lược trong suốt 7 thế kỷ sung túc và thịnh vượng của xứ Phù Nam. Vương quốc nầy có một chu vi hình tứ giác giữa vịnh Thái Lan và miền tây của đồng bằng sông Cửu Long (Transbassac) ở miền nam Việt Nam. Nó được bao bọc ở phía tây bắc bởi biên giới Kampuchia và về phía đông nam bởi các thị trấn Trà Vinh và Sóc Trăng. Những bức ảnh được người Pháp chụp từ trên không vào những năm 1920 mới tiết lộ rằng Phù Nam là một đế chế hàng hải (hay một cường quốc hải dương).Theo các tác giả Trung Hoa, các thành phố tự trị nầy được bao bọc bởi các thành lũy và các mương đầy cá sấu, nối tiếp kề nhau và được chia ra thành nhiều khu nhờ sự rẻ nhánh các kênh rạch và các đường giao thông. Người ta có thể hình dung được những ngôi nhà cùng các cửa hàng nhà sàn có ở chung quanh các thuyền đậu như ở thành phố Ý Venise hay ở các thành phố của miền bắc Âu Châu. Qua mạng lưới đáng kinh ngạc này được tạo thành từ các dãy kênh rạch được bố trí dọc thẳng theo hướng đông bắc /tây nam (từ sông Hậu ra biển) và liên lạc thông qua với nhau, ngừời ta khám phá được vai trò quan trọng của sông Hậu trong việc sơ tán được nước lũ ra biển. Nhờ vậy mới có thể rửa sạch đất bị phèn, đẩy lùi sự xâm nhập của các vùng nước lợ qua các trận lũ của sông Hậu, ưu đãi việc trồng lúa nổi và bảo đảm được việc cung cấp hàng hóa trong nước đến từ Trung Hoa, Mã Lai, Ấn Độ mà còn có luôn cả vùng Địa Trung Hải. Việc phát hiện ra các đồng tiền vàng với hình nộm của hoàng đế La Mã Antonin le Pieux, có từ năm 152 sau Công nguyên hay hoàng đế Marc Aurèle và các bức phù điêu của các vị vua Ba Tư dẫn chứng cho vai trò quan trọng của vương quốc này trong việc trao đổi hàng hóa ở đầu kỷ nguyên công giáo. Thậm chí còn có một kênh lớn nối từ thành phố hải cảng Óc Eo đến biển một mặt và mặt khác từ sông Mê Kông đến thành phố cổ Angkor Borei nằm ở thượng nguồn 90 cây số trên lãnh thổ Cao Miên. Đây có lẽ là thủ đô của xứ Phù Nam trong thời kỳ suy tàn. Đối với nhà khảo cổ học người Pháp Georges Coedès, sự nghi ngờ nầy không còn nữa vì vị trí của Angkor Borei tương ứng chính xác với Na-fou-na, được mô tả trong các văn bản Trung Quốc là thành phố mà các vị vua Phù Nam ẩn cư sau khi họ bị trục xuất ra khỏi cố đô của Phù Nam, Tö-mu. Thành phố nầy được xác định là thành phố Vyādhapura và nằm trong vùng Bà Phnom thuộc lãnh thổ Cao Miên bởi Georges Coedès. Sự phong phú của địa điểm khảo cổ này và sự đa dạng của các di tích cổ tìm thấy chứng minh được sự xác nhận của ông. Nhờ các vật thể được phát hiện qua các chiến dịch khai quật ở các địa điểm của văn hóa Óc Eo, chúng ta có thể nói rằng vương quốc này đã có được ba thời kỳ quan trọng trong quá trình tồn tại của nó:

- Thời kỳ đầu tiên, kéo dài từ thế kỷ thứ nhất đến thế kỷ thứ ba, được nỗi bật bởi các đồ làm với đất nung (đồ gốm, gạch, ngói), các đồ thủy tinh (ngọc trai và dây chuyền), các đồ kim hoàn (nhẫn, hoa tai), các loại đá được khắc (con dấu, vòng mặt nhẫn, ngọc hòn) và các đồ vật làm bằng đồng, sắt và đặc biệt nhất là thiếc.Chúng ta được chứng kiến sự chiếm đóng đầu tiên của con người trên các gò đất ở đồng bằng Óc Eo và trên các sườn núi thấp của núi Ba Thê. Môi trường sống ở đây là nhà sàn bằng gỗ. Việc chôn cất trong chum thường phổ biến ở Đông Nam Á vẫn còn được thực hiện. Công trình Ấn Độ hóa vẫn chưa có với sự vắng mặt của các di tích làm bằng tượng và tôn giáo. Nhưng vẫn có sự liên lạc thường xuyên giữa vương quốc này và Ấn Độ. Sự trao đổi thương mại được củng cố nhờ các cuộc liên minh địa phương và sự xuất hiện các tu sĩ Ấn Độ. Được giữ lại lâu hơn ở vương quốc này vì lúc có gió mùa, những người này tiếp tục dẫn dạy và thuyết giáo (Bà La Môn giáo, Phật giáo). Họ bắt đầu thuyết phục được những người bản địa và giúp họ thiết lập một mạng lưới thủy lực để giúp họ cách thức làm thoát nước ở đồng bằng mà cho đến tận bây giờ họ xem như kẻ thù nghịch với lũ lụt và làm cho nó trở nên « hữu ích » cho sự trồng trọt, môi trường sống và luôn cả việc chỉnh đốn vương quốc. Người Ấn được biết họ là những người thực hiện một cách tinh vi các công trình thủy lực nông nghiệp và trồng trọt. Đây là những gì chúng ta đã thấy được ở đất nước của người dân Ta-Mun (tamoul) dưới triều đại Pallava chẳng hạn. Việc trồng lúa nổi được chứng minh nhờ các dấu vết mà họ để lại trong việc sử dụng loại lúa này như là một chất tẩy dầu mỡ cho các đồ gốm. Đối với nhà nghiên cứu Pháp J.Népote, người chuyên nghiệp về bán đảo Đông Dương, vương quốc Phù Nam đã thu thập được cốt yếu của tất cả nguồn lực nông nghiệp của mình trong kỹ thuật trồng lúa nổi. Không cần phải canh tác hoặc phải gieo đất, cũng đừng nói đến việc cấy cây lúa vào thời điểm đó bởi vì các rìa bờ biển của Phù Nam là những khu vực đất lấn biển (polders). Cây lúa tự phát triển cùng với mực nước, nó có thể đạt tới ba mét chiều cao. Lúa sau đó nó được gặt thu hoạch bởi những chiếc thuyền. Đối với việc canh tác lúa nổi, sự ràng buộc duy nhất bị đòi hỏi là sự điều chỉnh và phân phối lũ lụt thông qua việc đào các kênh để quản lý nước tưới được tốt hơn và tạo điều kiện thuận lợi cho các phương tiện giao thông.

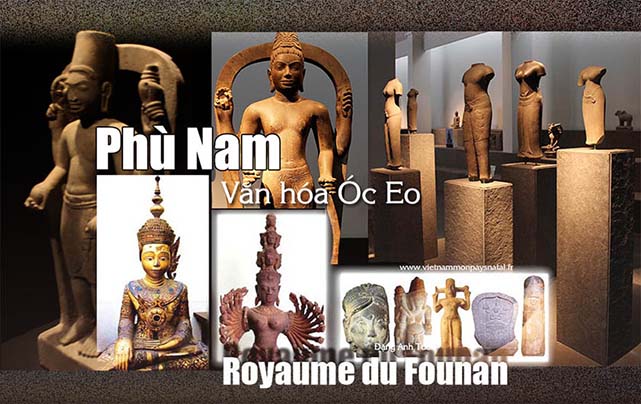

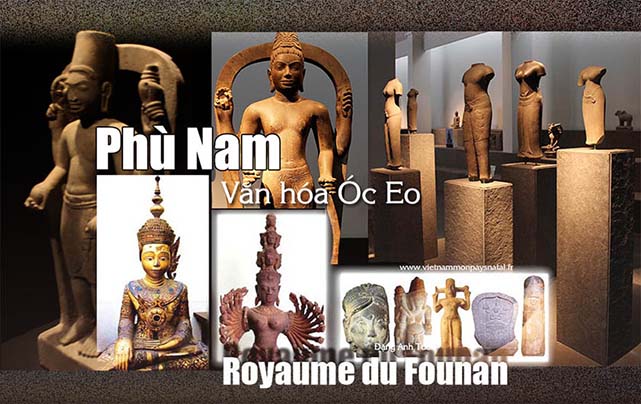

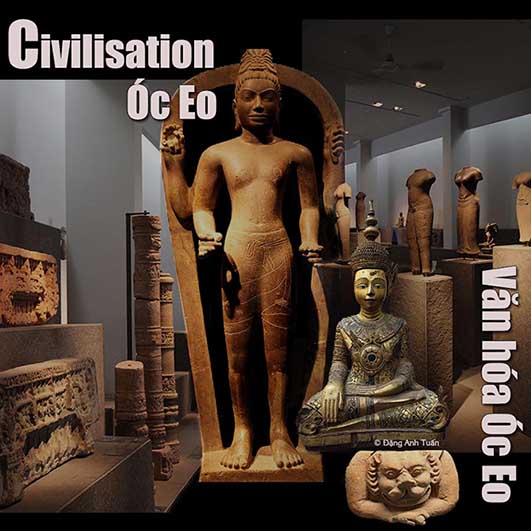

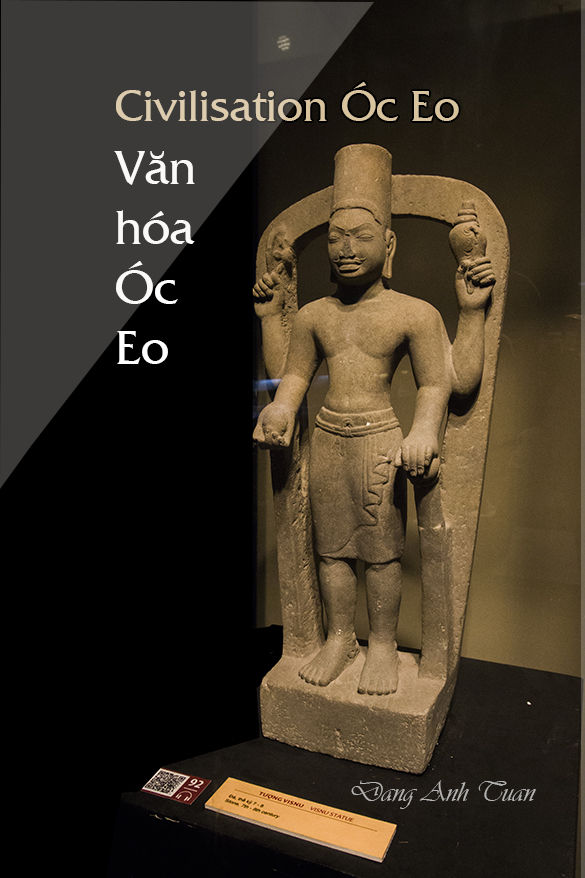

- Thời kỳ thứ hai của lịch sử Phù Nam (thế kỷ thứ 4 đến thế kỷ 7) được đánh dấu bằng việc phát hiện ra một số lượng lớn các di tích tôn giáo và Phật giáo Vishnu trên các gò của đồng bằng Óc Eo và trên các sườn núi Ba Thê. Các nhân vật biểu tượng của Ấn Độ ( như thần Shiva, Vishnu, Brahma, Nanin, Ganesha và Đức Phật) đã được khai quật. Đây cũng là thời kỳ mà các nhà sàn bằng gỗ được dời đi từ các gò đến các vùng ngập nước và các sườn núi dốc thấp của núi Ba Thê.Việc Ấn Độ hóa vương quốc được diễn ra khi một người Ấn Độ tên là Chu Tchan-t’an viết theo chữ Hán, sống vào khoảng năm 357, có thể là người gốc Xi-tơ (scythe) và thậm chí cũng có thể là gốc Kanishka, trị vì ở vương quốc Phù Nam [The Founan: Paul Pelliot, trang 269]. Có thể đây là sự giải thích việc thành công của giáo phái Surya và biểu tượng của nó trong nghệ thuật của người dân Phù Nam. Một người Bà la môn khác tên Trung Hoa là Kiao-Tchen-Jou (hay còn gọi là Kawa-Jayavarma) được kế vị sau đó và cai trị Phù Nam trong khoảng thời gian từ 478 đến 514. Đây là thời kỳ nổi tiếng nhờ có những văn khắc địa phương viết bằng tiếng Phạn. Ngay cả huyền thoại về việc thành lập vương quốc cũng được xuất phát từ Ấn Độ: Một người dũng sĩ Bà La môn tên là Kaundinya trong một giấc mơ có được một cây cung ma thuật trong một ngôi đền và hướng dẫn thuyền đến các bờ biển mà anh ta thành công đánh bại một người phụ nữ tên là Soma, con của một vị vua đang cai trị vùng bản địa được xem như là vua Naga (một con rắn tuyệt vời). Sau đó anh kết hôn với cô nầy để cai trị đất nước này. Có thể nói rằng trong thời kỳ này, vương quốc Phù Nam đã đạt đến đỉnh cao và duy trì mối quan hệ chặt chẽ với Trung Quốc.Sự phát triển thương mại của Phù Nam không thể chối cãi được khi phát hiện ra một số lượng lớn các vật thể không phải của Ấn Độ được tìm thấy ở trên bờ của Phù Nam: những mảnh gương bằng đồng có từ thời Tây Hán, các tượng phật bằng đồng được gán cho nhà Ngụy, một nhóm vật thể thuần túy La Mã, các bức tượng theo phong cách Hy Lạp, đặc biệt là một đại diện bằng đồng của thần Poseidon. Những đồ vật này có lẽ đã được trao đổi để lấy hàng vì người dân Phù Nam chỉ biết mậu dịch đổi hàng. Để mua hàng hóa có giá trị, họ sử dụng các thỏi vàng và bạc, ngọc trai và nước hoa. Họ được biết đến như những thợ kim hoàn xuất sắc. Vàng đã được gia công một cách tinh xảo với nhiều biểu tượng Bà la môn. Những đồ nữ trang (bông tai bằng vàng với cái móc tinh tế, những sợi vàng đáng ngưỡng mộ, các hạt thủy tinh, các đá màu chạm hình vân vân..) được trưng bày ở các bảo tàng của Đồng Tháp, Long An và An Giang chứng minh không những bí quyết và tài năng của họ mà còn là sự ngưỡng mộ của người Trung Hoa qua những câu chuyện mà họ có dịp tiếp xúc với người dân Phù Nam.

- Thời kỳ cuối cùng tương ứng với sự suy tàn và sự kết thúc của vương quốc Phù Nam. Một thay đổi quan trọng đã được báo cáo trong thời kỳ Cheng-kuan (627-649) tại vương quốc Founan trong biên niên sử Trung Quốc. Vương quốc Chen-la (Chân Lạp) (Campuchia tương lai) nằm ở phía tây nam Lâm Ấp (Champa tương lai) và là quốc gia chư hầu của Phù Nam xâm chiếm và chinh phục Phù Nam. Sự thật này đã được báo cáo không những trong lịch sử mới của nhà Đường (618-907) bởi nhà sử học Trung Hoa Ouyang Xiu, mà còn trên một bản khắc chưa được công bố của Sambor-Prei Kuk, trong đó nhà vua của Chân Lạp Içanavarman nhận được sự chúc mừng vì ông đã thành công mở rộng lãnh thổ của bố mẹ ông. Các khu nhà ở và các nơi tôn giáo ở đồng bằng Óc Eo đang bị bỏ hoang vì sự hình thành chính trị mới đến từ phương Bắc đang di chuyển tách rời bờ biển và tiếp cận dần dần địa điểm Angkor, thủ đô tương lai của Đế quốc Khơ Me. Đối với nhà nghiên cứu J. Népote, đến từ miền Bắc nước Lào xuất hiện dưới dạng các nhóm người Giéc Ma Ni với đế chế La Mã, nhóm người Khơ Me cố gắng tạo thành một vương quốc thống nhất ở nội địa với tên là Chân Lạp. Họ không thấy có lợi ích để giữ kỹ thuật trồng lúa nổi vì họ sống rất xa bờ biển. Họ cố gắng phối hợp những gì họ thông thạo hiểu biết trong cách giữ nước với sự bổ sung thêm khoa học thủy lực của người Ấn Độ để phát triển qua nhiều lần thử nghiệm, một hệ thống thủy lợi thích hợp hơn với hệ sinh thái của vùng nội địa và các giống lúa địa phương. Mặc dù có những khám phá gần đây xác nhận sự tồn tại của vương quốc này, nhiều câu hỏi vẫn chưa được có câu trả lời. Chúng ta không biết ai là người bản địa ở vương quốc này. Chúng ta chắc chắn một điều: họ không phải là người Việt Nam chỉ đến đồng bằng sông Cửu Long vào thế kỷ 17. Có phải họ là tổ tiên của người Khơ Me? Một số người tin chắc là vậy lúc thời điểm mà Louis Malleret bắt đầu khai quật vào những năm 40 bởi vì tên tuổi của khu vực hoàn toàn là tiếng Khơ Me. Vào thời Phù Nam, chúng ta vẫn chưa biết rõ họ là ai. Mặt khác, nhờ việc nghiên cứu về các di tích xương ở bán đảo Cà Mau, chúng ta tìm thấy được một dân số rất gần gũi với người Nam Á. Sự đóng góp của người Môn Khmer ở phía bắc của vương quốc này có thể nghĩ đến để mang lại cho Phù Nam sự kề nhau và hợp nhất của hai tầng lớp không xa nhau chi cho mấy trước khi trở thành chủng tộc Phù Nam. Trong giả thuyết được chấp nhận thường xuyên này, người dân Phù Nam là tổ tiên hoặc là người anh em họ của người Khơ Me. Sự gia nhập một thành phố từ bán đảo Mã Lai (được gọi là Dunsun theo các nguồn báo cáo của Trung Quốc) trong một khu vực mà ảnh hưởng của người Môn-Khmer không thể phủ nhận được ở thế kỷ thứ ba bởi Phù Nam là một trong những yếu tố chính dẫn đến sự ủng hộ giả thuyết này. Trong điều kiện nào Óc Eo bị biến mất? Tuy nhiên, Óc Eo đóng một vai trò kinh tế quan trọng trong việc trao đổi thương mại suốt bảy thế kỷ đầu tiên của kỷ nguyên Kitô giáo. Các nhà khảo cổ tiếp tục tìm kiếm nguyên nhân của sự biến mất của thành phố hải cảng này: lũ lụt, hỏa hoạn, đại hồng thủy, dịch bệnh vân vân… Vương quốc Phù Nam có phải là một quốc gia thống nhất với một quyền lực trung ương mạnh mẽ hay là một liên đoàn các trung tâm quyền lực chính trị được đô thị hóa và tự trị trên bán đảo Đông Dương như trên bán đảo Mã Lai để được gọi là các quốc gia thành phố? P.Y. Manguin đã nêu câu hỏi nầy tại một hội nghị chuyên đề do trung tâm Copenhagen Polis tổ chức tại các quốc gia ở ven biển Đông Nam Á vào tháng 12 năm 1998. Thủ đô của Phù Nam nằm ở đâu nếu quyền lực trung ương được nhấn mạnh nhiều lần bởi người Trung Quốc trong văn bản của họ? Angkor Borei, Bà Phnom có thực sự là thủ đô cổ của vương quốc này như đã được Georges Coèdes xác định? Cho đến nay, những gì đã được tìm thấy không cung cấp được câu trả lời mà chỉ làm tăng thêm gấp đôi sự mong muốn và khao khát của các nhà khảo cổ để tìm thấy trong những năm tới bởi vì họ có cảm giác có được một nền văn minh rực rỡ của đồng bằng sông Cửu Long.

Références bibliographiques

Georges Coedès: Quelques précisions sur la fin du Founan, BEFEO Tome 43, 1943, pp1-8

Bernard Philippe Groslier: Indochine, Editions Albin Michel, Paris

Lê Xuân Diêm, Ðào Linh Côn,Võ Sĩ Khai: Văn Hoá Oc eo , những khám phá mới (La culture de Óc Eo: Quelques découvertes récentes) , Hànôi: Viện Khoa Học Xã Hội, Hô Chí Minh Ville,1995

Manguin,P.Y: Les Cités-Etats de l’Asie du Sud-Est Côtière. De l’ancienneté et la permanence des formes urbaines.

Nepote J., Guillaume X.: Vietnam, Guides Olizane

Pierre Rossion: le delta du Mékong, berceau de l’art khmer, Archeologia, 2005, no422, pp. 56-65.