Version vietnamienne

Version anglaise

Deuxième partie

Quand on décide d’aller à l’étranger ( càd dans les autres villages voisins), on a besoin d’être accompagné par un entremetteur recruté de préférence sur les kuang du village. Un kuang est en fait un homme puissant et réputé qui ne se mesure pas à la fortune accumulée mais au nombre de sacrifices de buffles qu’il a organisés et accomplis. Grâce aux dépenses grandioses qu’il a entamées dans les sacrifices des buffles pour ses proches, ses invités jôok et son village, il a acquis du même coup un énorme prestige. Cela lui a permis d’élargir progressivement son réseau de relations, d’avoir du poids dans les délibérations du village et de devenir un rpuh kuang (ou un buffle mâle) au niveau de la puissance sexuelle.

Même les cornes de son « âme-buffle ( ou hêeng rpuh ) » élevée par les génies se sont allongées en fonction du nombre de sacrifices accomplis. Son cercueil pèse d’autant plus lourd que ces cornes ont atteint une taille imposante. Un grand kuang est celui qui ose pratiquer la stratégie de l’endettement. Plus il thésaurise pour dépenser dans les sacrifices des buffles et dans les achats, plus son prestige s’accroît. Il a toujours quelque dette à la traîne.

Il n’attend pas de rembourser l’intégralité de ses achats pour en faire d’autres car cela lui vaut l’admiration et la renommée. Un villageois mnong devient un kuang avec le premier sacrifice de buffle. Il devient ainsi l’homme « indispensable » sur lequel on s’appuie pour s’assurer non seulement la sécurité routière mais aussi la réussite dans les transactions commerciales lors du déplacement hors du village. C’est avec lui qu’on mettra au point l’itinéraire. C’est lui qui présentera, grâce à son réseau de relations, le jôok local du village destinataire qui connait tous les habitants et qui sait parmi ces derniers lequel intéressé par les objets entrant dans la transaction tout en présentant les garanties de solvabilité.

Analogues aux Bahnar, les Mnong sont des animistes. Ils pensent que toute chose a une âme même dans les ustensiles à usages rituels (les jarres à bière par exemple). L’univers est peuplé de génies (ou yaang).

C’est pourquoi l’appel aux divinités ne se cantonne pas dans un endroit particulier mais il s’éparpille partout soit dans le village soit dans les bois soit dans les monts et les eaux. Aucun recoin n’est épargné. Il sera soit évoqué collectivement soit honoré d’un culte spécial dans des circonstances particulières. C’est le cas du génie du riz auquel un petit autel est dédié au milieu du ray. Durant la saison des semailles, le Mnong viendra placer ses offrandes. La moisson collective ne peut pas commencer sans un rite spécial connu sous le nom de « Muat Baa » ou ( nouage du paddy ). Comme le paddy a une âme, il faut éviter de le faire courroucer et de le faire fuir en prenant soin d’un grand nombre de précautions: éviter de siffler, de pleurer, de chanter sur les champs ou de s’y disputer, de manger des concombres, des citrouilles, des œufs, des êtres glissants etc. Une poule sera sacrifiée près de la hutte miniature de l’âme du riz perchée sur un bambou lui-même cerné par des bambous portant des nids à offrandes. Au génie de la pluie, le Mnong offrira sur une minuscule plateforme des œufs. Pour calmer la colère des génies végétaux de la forêt avant le défrichement d’un pan, on procède à de grands soins rituels et de prières. Un long piquet de bambou à la pointe recourbée duquel a été suspendu un poisson pêché est planté sur le lieu consacré dans le défrichement à brûler.

Au moment où le feu commence à jaillir, deux « hommes sacrés »( croo weer ) implorent la protection des génies tandis qu’un troisième oint le piquet au poisson et appelle les génies. Même il y a des divinités censées d’être les gardiens de l’âme de l’individu. Celui-ci se compose d’un corps matériel et de plusieurs âmes (ou heêng). Celles-ci prennent des formes multiples: une âme-buffle élevée dans un étage des cieux par les génies, une âme-araignée dans la tête de l’individu, une âme-quartz qui loge tout droit derrière le front. Il y a même l’âme-épervier (kuulêel) symbolisé par une ficelle faite de brins de coton rouges et blancs et tendue au dessus du corps de défunt entre deux bambous pour distinguer le kuulêel de l’épervier ordinaire. Cette âme-épervier prend son envol à la mort de l’être humain. Un mal subi par l’une de ces âmes se répercute sur les autres. Les génies peuvent rendre malade quelqu’un en attachant son âme-buffle à leur poteau de sacrifice céleste. Le recours au chamane s’avère indispensable car lui seul peut établir le dialogue avec les génies lors de la séance de cure (mhö). Il tente de marchander le prix que les génies exigent pour libérer l’âme-buffle du malade sinon le malade meurt et l’un de ses autres âmes rejoint le premier des étages du monde souterrain. L’âme disparaît totalement lorsqu’il arrive à atteindre le septième étage souterrain au bout de la septième mort.

L’au delà est conçu comme souterrain. Le rite de guérison n’a pas de côté festif. Cela entraîne peu de frais à engager à part le buffle immolé et l’honoraire payé ( équivalent au nombre de hottées de paddy) au chamane qui reçoit en plus une cuisse de la bête sacrifiée. Chez les Mnong, la notion d’immortalité de l’âme n’existe pas. Par contre, la notion de réincarnation fait partie de la tradition des Mnong. Il peut arriver que l’ancêtre maintenu au premier étage souterrain se réincarne dans l’un de ses descendants.

Les hommes de la forêt

Musée d’ethnologie du Vietnam (Hanoi)

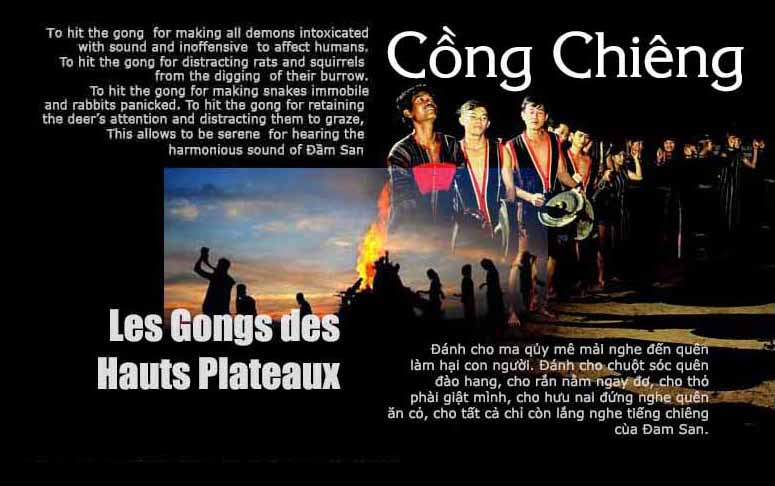

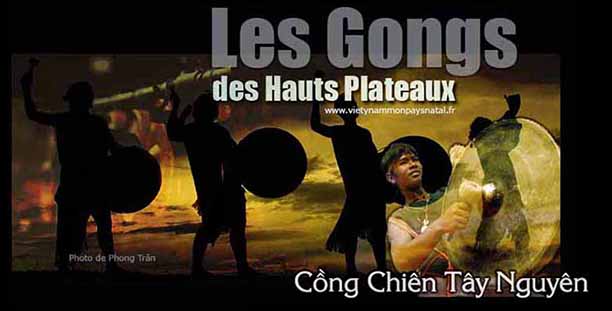

Dans la tradition mnong, le buffle est un animal sacré. Les Mnong ont recours au buffle comme monnaie d’évaluation. C’est aussi dans le système de croyances mnong que le buffle est l’équivalent de l’homme dont l’une de ses âmes est l’âme-buffle (hêeng rput) élevé au ciel par les génies à sa naissance et ayant un rôle prépondérant sur les autres âmes de l’individu. Avant d’être inhumé, le décédé est déposé dans un cercueil prenant approximativement la forme d’un buffle. Les Mnong n’organisent pas des funérailles et ils abandonnent le tombeau après un an d’inhumation. D’une manière générale, la maison de funérailles est construite sur une butte et elle est décorée avec des figurines sculptées en bois ou des motifs variés peints en noir, rouge ou blanc. La puissance d’un individu se mesure au nombre de bucrânes de buffles sacrifiés empilés et maintenus par des poteaux. Selon le mythe mnong, le buffle a remplacé l’homme dans le sacrifice. C’est pourquoi on voit dans ce sacrifice l’aboutissement suprême de tous les rites dont il se détache par le faste rituel animé par les processions de gongs, des jeux de tambours, des invocations d’appel aux esprits, des chants etc … et accompagné par des libations de bière, ce qui en fait un événement majeur et exceptionnel dans la vie villageoise.

Dans la tradition mnong, le buffle est un animal sacré. Les Mnong ont recours au buffle comme monnaie d’évaluation. C’est aussi dans le système de croyances mnong que le buffle est l’équivalent de l’homme dont l’une de ses âmes est l’âme-buffle (hêeng rput) élevé au ciel par les génies à sa naissance et ayant un rôle prépondérant sur les autres âmes de l’individu. Avant d’être inhumé, le décédé est déposé dans un cercueil prenant approximativement la forme d’un buffle. Les Mnong n’organisent pas des funérailles et ils abandonnent le tombeau après un an d’inhumation. D’une manière générale, la maison de funérailles est construite sur une butte et elle est décorée avec des figurines sculptées en bois ou des motifs variés peints en noir, rouge ou blanc. La puissance d’un individu se mesure au nombre de bucrânes de buffles sacrifiés empilés et maintenus par des poteaux. Selon le mythe mnong, le buffle a remplacé l’homme dans le sacrifice. C’est pourquoi on voit dans ce sacrifice l’aboutissement suprême de tous les rites dont il se détache par le faste rituel animé par les processions de gongs, des jeux de tambours, des invocations d’appel aux esprits, des chants etc … et accompagné par des libations de bière, ce qui en fait un événement majeur et exceptionnel dans la vie villageoise.

Personne ne peut se soustraire à cet événement. Le village devient une aire sacrée où on doit s’amuser collectivement, bien boire, bien manger et éviter de se disputer car on pourrait courroucer les esprits. Les Mnong sont divisés en plusieurs sous-groupes ( Mnông Gar, Mnông Chil, Mnông Nông, Mnông Preh, Mnông Kuênh, Mnông Prâng, Mnông Rlam, Mnông Bu đâng, Mnông Bu Nor, Mnông Din Bri , Mnông Ðíp, Mnông Biat, Mnông Bu Ðêh, Mnông Si Tô, Mnông Káh, Mnông Phê Dâm ). Chaque groupuscule a une dialecte différente mais d’une manière générale, les Mnong issus de ces groupuscules différents arrivent à se parler sans aucune difficulté apparente.

Ceints d’un long pagne de coton indigo dont l’extrémité frangée de cuivre et de laine rouge leur retombe à mi-cuisse comme un petit tablier (suu troany tiek)(3) , les Mnong se présentent souvent sous l’aspect des hommes fiers aux membres longs et au torse nu musclé et bronzé malgré les souffrances d’une vie précaire. Cette ceinture-tablier sert à porter toutes sortes d’objets: le couteau, l’étui à tabac, le poignard et les talismans individuels (ou pierres-génies ). Ils se servent d’une veste soit courte soit longue ou d’une couverture comme manteau à la saison froide. On trouve sur leurs têtes un turban noir ou blanc ou un chignon où est piqué souvent un couteau de poche en acier et à manche recourbé. Ils sont habitués à porter une hache pour abattre les troncs d’arbres.

Les femmes mnong aux seins nus portent une jupe courte (suu rnoôk) enroulée au niveau du bas-ventre. Les Mnongs adorent les parures. Ils portent au cou des pectoraux, des colliers de fer ou en perles de verre ou des dents de chiens provenant d’un rite exorciste qui leur confèrent des propriétés protectrices.

Des bobines d’ivoire enfilées dans les lobes percés de leurs oreilles battent leurs maxillaires. Les femmes aiment particulièrement les colliers en verre de perles. Les lobes de leurs oreilles sont distendus souvent par de gros disques en bois blanc. On trouve encore dans la plupart des groupuscules mnong l’abrasion des dents de devant (de la mâchoire supérieure). Les hommes comme les femmes fument du tabac et consomment beaucoup de bière de riz. Celle-ci est non seulement un élément indispensable dans toutes les fêtes et dans les cérémonies rituelles mais aussi une boisson d’hospitalité. En l’honneur de son hôte, une jarre de bière de riz est débouchée quelques instants avant d’être offerte. Sa consommation se fait collectivement à l’aide d’un ou plusieurs chalumeaux en bambou plantés dans la jarre. Le nombre de mesures est imposé au buveur par la tradition de chaque ethnie. ( 2 chez les Mnongs Gar, 1 chez les Edê ). Pour maintenir le niveau de la jarre, on est obligé d’y verser de l’eau, ce qui dilue progressivement l’alcool de la bière de riz et qui transforme ce dernier en une boisson inoffensive.

Analogues aux Bahnar, les Mnong (ou les Hommes de la Forêt) sont fiers d’être des gens libres. C’est ce qu’a constaté l’ethnologue célèbre G. Condominas auprès des Mnongs Gar. Dans le village de Sar Luk où il a fait un an d’immersion complète avec les Mong Gar, il n’y avait pas de chef de village mais un groupe de trois ou quatre hommes sacrés qui sont des guides rituels notamment en matière agricole. La perte de leur liberté peut être le catastrophe que redoutent les Mnong. On trouve toujours en eux deux particularités qui les différencient des autres groupes ethniques du Vietnam: leur esprit d’abnégation et de solidarité et leur absence de s’enrichir égoïstement.

Malgré les souffrances de leur vie précaire, les Mnong démunis connaissent encore la notion de partage que nous, les gens dits civilisés, avons oubliée depuis longtemps.

[Retour à la page « Vietnam des 54 ethnies »]

Références bibliographiques

De la monnaie multiple. G. Condominas. Communications 50,1989,pp.95-119

Essartage et confusionisme: A propos des Mnong Gar du Vietnam Central. Revue Civilisations. pp.228-237

Les Mnong Gar du Centre Vietnam et Georges Condominas. Paul Lévy L’homme T 9 no 1 pp. 78-91

La civilisation du Végétal chez les Mnong Gar. Pierre Gourou. Annales de géographie. 1953. T.62 pp 398-399

Tiễn đưa Condo của chúng ta, của Tây Nguyên. Nguyên Ngọc

Chúng tôi ăn rừng …Georges Condominas ở Việtnam. Editeur Thế Giới 2007

Ethnic minorities in Vietnam. Đặng Nghiêm Vạn, Chu Thái Sơn, Lưu Hùng . Thế Giới Publishers. 2010

Mosaïque culturelle des ethnies du Vietnam. Nguyễn Văn Huy. Maison d’édition de l’Education. Novembre 1997

Les Mnongs des hauts plateaux. Maurice Albert-Marie 1993. 2 tomes, Paris, L’Harmattan, Recherches asiatiques.