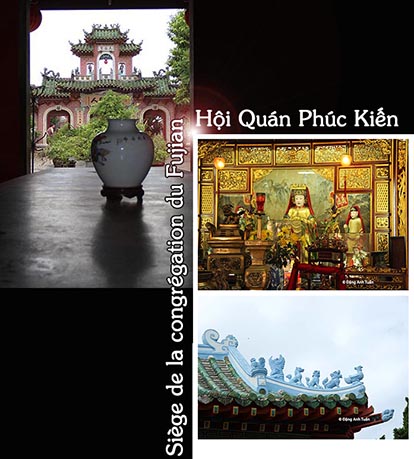

Hôi Quán Phúc Kiến

Vietnam

Histoire du Vietnam

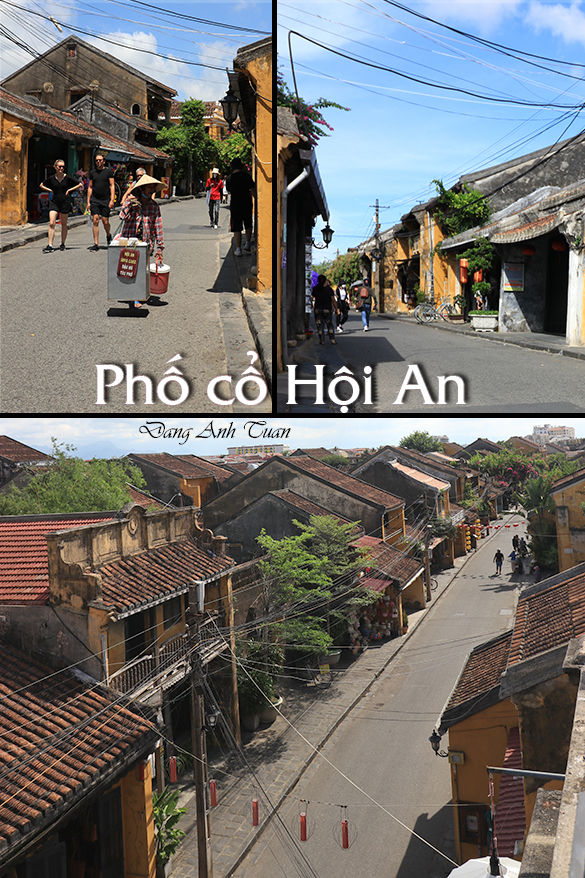

Hoi An et ses maisons historiques (2ème partie)

On trouve aujourd’hui à Hội An deux types de maisons: maisons donnant sur la rue (nhà phố) et maisons analogues à celles trouvées dans les champs de rizières (nhà rường). Quel que soit le type de maison, sa construction nécessite au préalable l’étude du terrain bâti et de l’aménagement intérieur en accord avec les règles de la géomancie ou Feng Shui (Phong Thủy) dans le but de chercher l’énergie positive de l’environnement permettant d’apporter santé, richesse et bonheur au nouveau propriétaire. Les maisons donnant sur la rue sont en fait des boutiques accessibles à la fois à la rue et à la rivière. Leur devant sert à accueillir les clients tandis que leur arrière permet de faciliter le transport et l’évacuation des marchandises par la rivière. Contrairement aux temples ou aux sièges des congrégations, ces maisons n’ont ni verdure ni clôture. D’une manière générale, elles doivent remplir plusieurs fonctions à la fois: boutique, habitation et emmagasinage. Pour répondre à cette exigence, ces maisons ont été construites selon un ordre linéaire très précis en profondeur:

véranda–bâtiment principal–cour–bâtiment postérieur — cuisine et toilette

Les maisons traditionnelles se font remarquer surtout par leur longueur. Pour cette raison, elles sont appelées souvent sous un autre nom « nhà chuột (trou des rats) ». Sur la rue, elles sont alignées étroitement les unes sur les autres et sont séparées par des impasses (ou ruelles ) assez larges et éclairées . C’est une autre particularité trouvée auprès des maisons traditionnelles.

En fonction de la profondeur de la maison (allant de 10 à 40 m), le nombre de bâtiments peut varier. Mais la maison « nhà phố » doit comporter au minimum deux bâtiments séparés soit par une cour et un petit jardin en miniature soit un passage couvert. Cela permet de relier la structure d’avant destinée à servir les clients et à accueillir les invités, à celle de derrière consacrée à l’emmagasinage des marchandises et à l’habitation familiale. À l’arrière du bâtiment postérieur de la maison, se trouve un espace où on installe la cuisine, le puits et la toilette.

On a l’habitude d’attribuer aussi à ces maisons traditionnelles le nom de « maisons- couloirs » car on prend soin de séparer toujours le couloir de l’espace réservé au commerce et à l’habitation pour faciliter non seulement la circulation mais aussi l’aération. On constate que le couloir occupe une partie particulièrement importante dans la superficie totale de la maison. De plus, pour faciliter l’aération de chaque bâtiment, on est habitué à mettre en place la double toiture (constituée d’un grand et d’un petit toit) et à surhausser les chevrons (rui nhà) de chaque toit grâce à la structure de style Gassho (2) et celle d’un seul pilier. Cela permet de stabiliser les deux toits dont chacun est bien fixé sur son propre angle et d’empêcher la filtration d’eau dans la maison en les alignant de façon parallèle. Plus les chevrons sont élevés, plus le commerce fonctionne mieux.(Rui cao, làm ăn tốt). C’est le maxime des Japonais mais c’est peut-être aussi l’une des explications de l’utilisation fréquente de cette technique dans la construction des maisons traditionnelles à Hội An. Il ne faut pas oublier que la plupart de leurs maisons ont été ré-achetées par les commerçants chinois et que leur influence dans la construction n’a pas décliné au fil des années.

Dans la région de Thừa Thiên Huế comme celle de Quảng Trị, les structures de style Gassho et d’un seul pilier sont fréquemment rencontrées et elles sont particulièrement importantes. Ce sont des structures qui sont considérées souvent comme celles de style vietnamien. Même, à l’intérieur de la cité interdite de Huế, on constate que son architecture a une structure mélangeant à la fois les styles vietnamien et chinois. À cause de la proximité de Huế, certains spécialistes trouvent que la structure des maisons traditionnelles de Hội An ont une étonnante ressemblance à celle de la cité impériale de Huế. C’est à partir de cette constatation qu’on les considère désormais comme un héritage précieux de la culture du Centre du Vietnam. Lire la suite (Tiếp theo)

Hội An với những nhà cổ truyền thống

Dù là kiểu nhà nào đi chăng nữa thì việc xây dựng nhà cũng cần phải có sự nghiên cứu sơ bộ về khu đất xây dựng và cách bố trí nội thất để được phù hợp với quy luật địa lý phong thủy và nhằm tìm kiếm năng lượng tích cực của môi trường hầu mang lại sức khỏe, sự giàu có và hạnh phúc cho chủ căn nhà mới. Những ngôi nhà quay mặt ra đường thực chất là những cửa hàng được thông ra cả đường lẫn sông. Mặt trước của nhà được sử dụng để tiếp đón khách hàng trong khi phía sau nhà thì thuận lợi cho việc vận chuyển và di tản hàng hóa bằng đường sông. Không giống như các ngôi đền hoặc các nhà của hội đoàn, những ngôi nhà này không có cây cỏ hoặc hàng rào. Nói chung, các nhà nầy phải thực hiện một số chức năng cùng một lúc: cửa hàng, nhà ở và kho chứa đồ. Để đáp ứng yêu cầu này, những ngôi nhà này được xây cất mang tính chất nói tiếp nhau theo đường thẳng và rất chính xác với chiều sâu:

Hiên nhà – tòa nhà chính – sân trong – tòa nhà phía sau – bếp và nhà vệ sinh.

Những ngôi nhà truyền thống đặc biệt nầy được nổi bật nhờ chiều dài. Vì lý do này, chúng thường được gọi dưới một cái tên khác là « nhà chuột (ổ chuột) ». Ở mặt đường, các nhà được nối tiếp nhau một cách chặc chẽ và được cách xa nhau bởi những ngõ cụt khá rộng và sáng suốt. Đây là một đặc thù khác được tìm thấy với những ngôi nhà truyền thống.

Tùy theo độ sâu của ngôi nhà (từ 10 đến 40 thước) mà số lượng toà nhà có thể thay đổi. Nhưng ngôi nhà mà đựợc gọi là « nhà phố” phải gồm ít nhất hai toà nhà cách xa nhau bởi một cái sân và một khu vườn nho nhỏ hay là một lối đi có mái che. Điều này làm cho ngôi nhà có thể kết nối lại cấu trúc ở phiá trước đây nhằm để phục vụ khách hàng và tiếp đón khách với cấu trúc ở phía sau dành cho việc lưu trữ hàng hóa và nơi ở của gia đình. Ở phía sau của toà nhà ở đằng sau của ngôi nhà thì có một không gian được bố trí để có một gian bếp, một cái giếng và nhà vệ sinh.

Người ta c ó thói quen hay gán cho những ngôi nhà truyền thống này cái tên « nhà hành lang » vì họ luôn chú ý việc tách hành lang ra khỏi không gian dành cho mậu dịch và nhà ở để tạo điều kiện thuận lợi không chỉ cho sự giao thông mà còn tiện bề cho sự thông gió. Có thể thấy được hành lang chiếm một phần đặc biệt quan trọng trong tổng diện tích của ngôi nhà. Ngoài ra, để tạo sự thông thoáng cho mỗi tòa nhà, người ta thường sử dụng cách lắp đặt mái đôi (gồm một mái lớn và một mái nhỏ) và nâng cao các rui nhà của mỗi mái nhờ cấu trúc của một trụ duy nhất và theo kiểu Gassho (2).

Điều này giúp việc ổn định hai mái nhà, mỗi mái được bố trí ở một góc độ riêng và ngăn cặn được nước không vào nhà bằng cách sắp xếp hai mái được song song. Rui nhà càng cao thì việc buôn bán càng thuận lợi (Rui cao, làm ăn tốt). Đây là câu châm ngôn của người Nhật nhưng có lẽ cũng là một trong những lời giải thích cho việc sử dụng thường xuyên kỹ thuật này trong việc xây dựng các ngôi nhà truyền thống ở Hội An.

Cần nên nhớ rằng hầu hết các ngôi nhà của họ đã được các thương nhân Trung Quốc mua lại và ảnh hưởng của họ trong lĩnh vực xây dựng không hề suy giảm qua nhiều năm.

Ở khu vực Thừa Thiên Huế như Quảng Trị, phong cách Gassho và các cấu trúc cột đơn thường xuyên được gặp và có ý nghĩa đặc biệt quan trọng. Đây là những cấu trúc thường được coi là mang phong cách riêng của người dân Việt. Ngay bên trong Tử Cấm Thành Huế, chúng ta có thể thấy kiến trúc có cấu trúc đựợc pha trộn giữa phong cách Việt Nam và Trung Quốc. Vì gần với Huế, một số học giả nhận thấy rằng cấu trúc của các ngôi nhà truyền thống của Hội An có sự tương đồng đáng ngạc nhiên với kiến trúc của kinh thành Huế. Chính từ nhận định này, các ngôi nhà được xem coi là một di sản quý giá của văn hóa miền Trung Việt Nam. [Đọc tiếp: Phần 3]

Forme de triangle pentu de deux éléments inclinés regroupés ensemble au

sommet comme deux mains jointes en prière (Gassho).

Today in Hội An, there are two types of houses: houses facing the street (nhà phố) and houses similar to those found in rice fields (nhà rường). Regardless of the type of house, its construction requires prior study of the built terrain and interior layout in accordance with the rules of geomancy or Feng Shui (Phong Thủy) in order to seek the positive energy of the environment that brings health, wealth, and happiness to the new owner. The houses facing the street are actually shops accessible both from the street and the river. Their front serves to welcome customers while their back facilitates the transport and evacuation of goods by river. Unlike temples or the headquarters of congregations, these houses have neither greenery nor fences. In general, they must fulfill several functions at once: shop, residence, and storage. To meet this requirement, these houses were built according to a very precise linear order in depth:

veranda–main building–courtyard–rear building — kitchen and toilet

Traditional houses are especially notable for their length. For this reason, they are often called by another name « nhà chuột (rat hole). » On the street, they are closely aligned with each other and separated by fairly wide and well-lit alleys (or lanes). This is another characteristic found in traditional houses.

Depending on the depth of the house (ranging from 10 to 40 meters), the number of buildings can vary. But the « nhà phố » house must have at least two buildings separated either by a courtyard and a small miniature garden or a covered passage. This allows connecting the front structure, intended to serve customers and welcome guests, to the rear one dedicated to storing goods and family living. Behind the rear building of the house, there is a space where the kitchen, well, and toilet are installed.

These traditional houses are also commonly referred to as « corridor houses » because care is always taken to separate the corridor from the areas designated for commerce and habitation, to facilitate not only movement but also ventilation. It is observed that the corridor occupies a particularly significant portion of the total area of the house. Furthermore, to facilitate the ventilation of each building, it is customary to implement double roofing (consisting of a large and a small roof) and to raise the rafters (rui nhà) of each roof using the Gassho-style structure (2) and that of a single pillar. This stabilizes the two roofs, each firmly fixed at its own corner, and prevents water from leaking into the house by aligning them parallel to each other. The higher the rafters, the better the business performs (Rui cao, làm ăn tốt). This is a Japanese maxim but may also be one of the reasons for the frequent use of this technique in the construction of traditional houses in Hội An. It should not be forgotten that most of their houses were repurchased by Chinese merchants and that their influence on construction has not diminished over the years.

In the Thừa Thiên Huế region, as well as in Quảng Trị, Gassho-style and single-pillar structures are frequently encountered and are particularly important. These are structures often considered to be of Vietnamese style. Even within the Imperial City of Huế, it is observed that its architecture has a structure blending both Vietnamese and Chinese styles. Due to the proximity of Huế, some specialists find that the structure of traditional houses in Hội An bears a striking resemblance to that of the Imperial City of Huế. It is based on this observation that they are now regarded as a precious heritage of Central Vietnam’s culture. [Reading more :Part 3]

Bibliographie

- Hội An. Hữu Ngọc- Lady Borton. Editeur Thế Giới

- Patrimoine architectural, urbain, aménagement et tourisme: la ville Hội An, Việtnam. Huỳnh Thị Bảo Châu, thèse doctorat de l’université Toulouse 2, Juillet 2012.

- Ancient town of Hội An thrives today. World heritage Hội An. Showa Women’s university of International Culture. Japan.

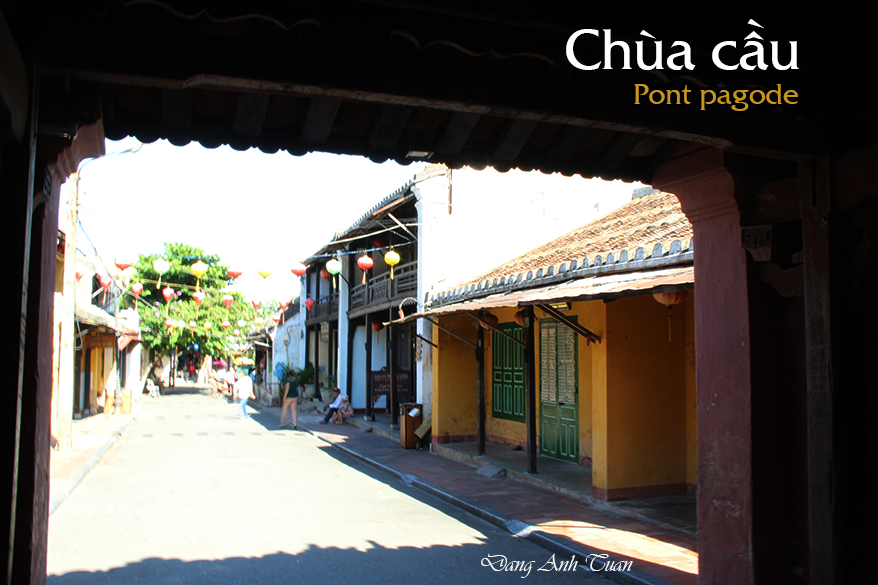

Hôi An et son pont-pagode (Chùa cầu)

Version vietnamienne

Version anglaise

Galerie des photos

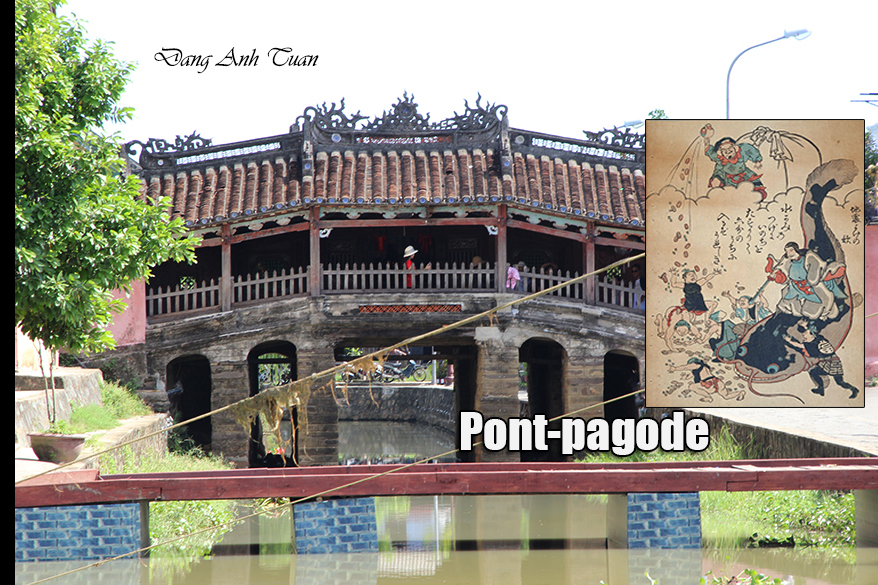

L’histoire du pont-pagode de Hội An

Certains historiens attribuent la construction de ce pont aux Japonais. Ces derniers l’ont-ils construit eux-mêmes ou l’ont-ils réalisé sur la commande des Chinois ? C’est une énigme historique qui reste à éclaircir. D’autres experts réfutent totalement cette hypothèse. Ils estiment que ce pont doit être attribué aux Japonais dans la mesure où celui-ci est destiné à mieux signaler l’entrée du quartier japonais. En tout cas, ce pont s’avère nécessaire car il est établi sur un grand arroyo où les crues surviennent à la saison des pluies dans le but de faciliter la circulation des véhicules, des chevaux et des piétons dans les deux quartiers de Hội An et de relier aujourd’hui les rues de Trần Phú et Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai. Ce pont est constitué de deux parties : le pont lui-même et la pagode. À l’entrée et à la sortie de ce pont on relève la présence de quatre statuettes de chien et de singe. Certains pensent que les travaux de construction ont commencé dans l’année du singe et achevé dans l’année du chien. D’autres attribuent cette présence à un usage japonais qu’il est temps de chercher à comprendre. Quant à la pagode, elle est située à côté de ce pont et en bois. On trouve sur sa porte principale une enseigne intitulée « Lai Viễn Kiều » qui est un autographe royal laissé par le seigneur Nguyễn Phước Châu lors de sa visite en l’an 1719 à Hội An.

Auparavant, cette pagode est dédiée au culte de Huyền Thiên Đại Đế (ou Bắc Đế Trần Vũ), un personnage éminent du taoïsme chargé de gouverner la partie Nord du ciel et d’avoir la mainmise sur le poisson-chat géant (Namazu) vivant dans la vase des profondeurs de la terre. Selon le mythe japonais, cet animal aquatique a la tête au Japon et la queue en Inde et la partie dorsale se trouve à l’endroit où s’érige le pont. Chaque fois qu’il retourne son dos, cela provoque des séismes au Japon et Hội An ne peut pas se tenir dans la paix pour permettre à ses habitants d’avoir la prospérité dans le commerce. C’est pour cela qu’on érige une pagode considérée comme une épée transperçant son dos afin de l’immobiliser et de l’empêcher de faire grands ravages. De toute façon, grâce au talent des architectes de cette époque, on constate que ce pont-pagode peut résister aux crues capricieuses de l’arroyo au fil du temps. Ce pont-pagode devient le symbole représentatif de la vieille ville de Hội An.

Version vietnamienne

Một số sử gia cho rằng việc xây dựng chùa cầu này đến từ người Nhật Bản. Họ tự xây dựng nó hay người Hoa thuê họ làm việc nầy ? Đó là một bí ẩn lịch sử cần được làm sáng tỏ. Các chuyên gia khác bác bỏ hoàn toàn giả thuyết này. Họ tin rằng cầu này được người Nhật dựng lên vì nó nhằm đánh dấu lối vào khu phố Nhật Bản. Trong mọi trường hợp, chiếc cầu này rất cần thiết vì nó được xây dựng trên một con sông lớn, nơi thường xảy ra lũ lụt vào mùa mưa nhằm tạo ra điều kiện thuận lợi cho việc di chuyển xe cộ, ngựa và người đi bộ ở hai khu phố của Hội An và kết nối hai đường phố Trần Phú và Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai ngày nay.

Cầu này gồm hai phần: một phần là cầu và một phần là chùa. Ở lối vào và lối ra của chùa cầu nầy, người ta nhận thấy có sự hiện diện của bốn tượng chó và khỉ. Một số người cho rằng việc xây dựng khởi đầu vào năm Thân và hoàn thành vào năm Tuất. Những người khác cho rằng sự hiện diện này là một tập tục của người Nhật mà cần phải nghiên cứu và tìm hiểu. Về phần chùa, nó nằm sát cạnh cầu này và được làm bằng gỗ. Trên cửa chính cũa chùa có một tấm biển đề « Lai Viễn Kiều » là ngự bút của chúa Nguyễn Phước Châu trong cuộc viếng thăm Hội An vào năm 1719.

Ngôi chùa này được thờ phụng trước kia Huyền Thiên Đại Đế (hay Bắc Đế Trần Vũ), một nhân vật nổi tiếng của Lão giáo, có nhiệm vụ cai trị phần phía bắc của trời và có tài năng kiểm soát được con cá trê khổng lồ sống ở đất bùn từ sâu của lòng đất. Theo truyền thuyết của người Nhật, loài vật sống dưới nước này có đầu ở Nhật Bản, đuôi nằm ở Ấn Độ và phần lưng của nó thì là nơi dựng chùa cầu. Mỗi lần nó quay lưng lại thì gây ra sự động đất ở Nhật Bản và Hội An cũng không thể yên ổn để cho người dân có được sự thịnh vượng trong mậu dịch. Đây là lý do tại sao một ngôi chùa được dựng lên và được xem coi như là một thanh gươm đâm vào lưng nó để cố giữ nó lại và ngăn nó tàn phá. Dù thế nào đi nữa, nhờ sự tài hoa của các nhà kiến trúc sư thời bấy giờ mà chùa cầu này có thể chống chọi với những trận lũ kinh hoàng theo dòng thời gian. Chùa cầu này trở thành ngày nay một biểu tượng tiêu biểu của phố cổ Hội An.

Some historians attribute the construction of this bridge to the Japanese. Did they build it themselves or did they do it on the order of the Chinese? It is a historical mystery that remains to be clarified. Other experts completely refute this hypothesis. They believe that this bridge should be attributed to the Japanese insofar as it is intended to better mark the entrance to the Japanese quarter. In any case, this bridge proves necessary because it is built over a large arroyo where floods occur during the rainy season in order to facilitate the movement of vehicles, horses, and pedestrians between the two quarters of Hội An and today connects Trần Phú and Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai streets. This bridge consists of two parts: the bridge itself and the pagoda. At the entrance and exit of this bridge, there are four statuettes of a dog and a monkey. Some think that the construction work began in the year of the monkey and was completed in the year of the dog. Others attribute this presence to a Japanese custom that it is time to try to understand. As for the pagoda, it is located next to this bridge and is made of wood. On its main door, there is a sign titled « Lai Viễn Kiều, » which is a royal autograph left by Lord Nguyễn Phước Châu during his visit to Hội An in the year 1719.

Previously, this pagoda was dedicated to the worship of Huyền Thiên Đại Đế (or Bắc Đế Trần Vũ), a prominent figure in Taoism responsible for governing the northern part of the sky and having control over the giant catfish (Namazu) living in the mud of the earth’s depths. According to Japanese myth, this aquatic animal has its head in Japan, its tail in India, and its dorsal part is located where the bridge stands. Each time it turns its back, it causes earthquakes in Japan, and Hội An cannot remain peaceful, preventing its inhabitants from prospering in trade. That is why a pagoda was erected, considered as a sword piercing its back to immobilize it and prevent it from causing great destruction. In any case, thanks to the talent of the architects of that time, it is observed that this bridge-pagoda can withstand the capricious floods of the arroyo over time. This bridge-pagoda has become the representative symbol of the old town of Hội An.

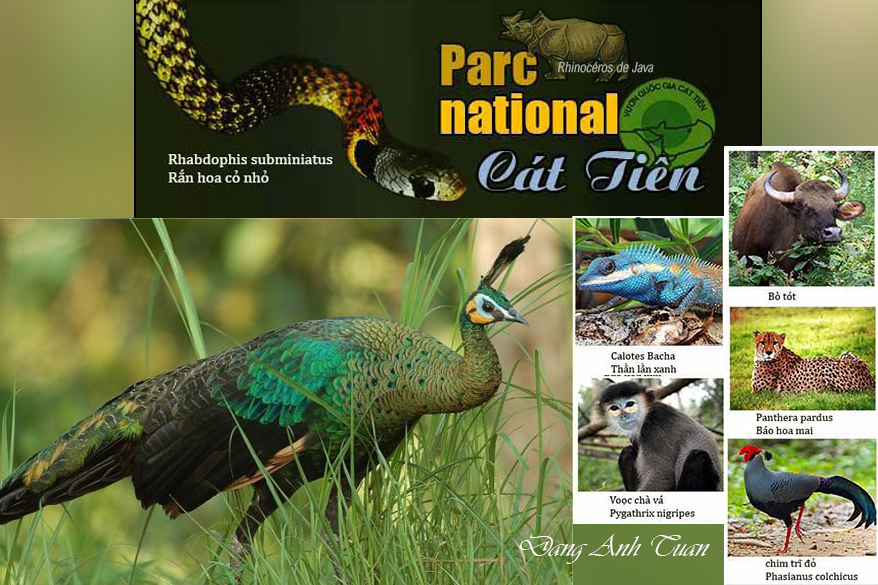

Parc national Cát Tiên (Vườn quốc gia Cát Tiên)

English version

French version

Mặc dù vườn quốc gia Cát Tiên được công nhận là khu dự trữ sinh quyển thế giới vào tháng mười một năm 2001 bởi cơ quan UNESCO và con tê giác Java được chọn làm biểu tượng cho vườn, các cơ quan chức năng Việt Nam không cứu được con tê giác cuối cùng bị một kẻ săn trộm bắn chết vào năm 2010. Điều này cho thấy việc bảo vệ công viên này rất khẩn cấp. Đây là khu rừng đất thấp cuối cùng ở Việt Nam có được sự đa dạng sinh học đáng chú ý. Sự mong manh của khu vườn nầy phần lớn là do nạn phá rừng kịch liệt có liên quan đến việc sử dụng chất làm rụng lá hóa học (chất da cam) trong những năm chiến tranh và sự phát triển kinh tế mà Việt Nam cần có sau khi thống nhất đất nước. Được tăng trưởng từ 48 triệu dân năm 1975 lên đến 96 triệu năm 2020, Việt Nam trở thành một trong những quốc gia đông dân nhất ở Đông Nam Á.

Mặc dù chính phủ cố gắng phục hồi rừng nhưng cũng không đủ để cứu các rừng thiên nhiên, đặc biệt là vườn quốc gia Cát Tiên. Trước hết, lợi ích quốc gia không tạo được tiếng vang thuận lợi trong cộng đồng dân cư địa phương vì họ tiếp tục sử dụng gỗ rừng làm vật liệu xây dựng nhà cửa và làm giảm bớt đi diện tích rừng bằng cách chuyển đổi những khu rừng nầy thành khu trồng cà phê và hạt điều, chưa kể đến sự suy thoái thông thường thấy với việc đốt rừng làm rẫy của các đồng bào thiểu số. Việc trồng lại rừng cũng không ngăn chặn được tổng diện tích rừng nguyên sinh nó giảm lần từ 3840 kilômét vuông xuống còn 800 kilô mét vuông.

Ngoài ra, chúng ta hay thường hủy họai thiên nhiên vì chúng ta không biết rằng nó rất cần thiết cho cuộc sống và sức khỏe. Việc giết một con bò tót sống gần đây ở Công viên Cát Tiên vào tháng 10 năm 2012 là một bằng chứng việc làm sai trái của con người do sự nghèo đói và thiếu hiểu biết. Con người cần có thiên nhiên nhất là con người chỉ là một phần nhỏ bé của thiên nhiên. Con người cần quan tâm sống hài hoà với thiên nhiên bởi vì nên biết rằng việc duy trì đa dạng sinh học là điều rất cần thiết cho loài người.

Theo nhà sinh vật học người Pháp Gilles Bœuf, 50% các phân tử hoạt động được sử dụng trong dược phẩm đến từ các sản phẩm tự nhiên hoặc thực vật. Rừng nhiệt đới Cát Tiên là một hệ sinh thái phức tạp mà sự cân bằng rất mong manh vì có một khu định cư trong vườn này. Ngoài ra, dự án xây dựng hai đập thủy lực ở thượng nguồn hồ cá sấu trên sông Đồng Nai có thể làm phá vỡ sự cân bằng này và có ảnh hưởng đến toàn bộ hệ sinh thái vì thực vật và động vật phụ thuộc vào nhau. Sự đòi hỏi kiên định các không gian sống và tài nguyên tạo thành một mối đe dọa ngày càng tăng và một áp lực mạnh mẽ lên hệ thực và động vật của công viên. Rất khó để tìm ra được sự cân bằng thích hợp cho môi trường và cho sự phát triển kinh tế.

Nhưng rất cần có sự quan tâm của chúng ta trong việc bảo vệ công viên Cát Tiên này vì nơi đây có hơn 1.610 loài thực vật, trong đó có 38 loài có tên trong Sách Đỏ, có hơn 350 loài chim (làm tổ hoặc di cư), 120 loài bò sát và các động vật lưỡng cư, 105 động vật có vú. Chúng ta có thể trích dẫn ví dụ như con báo mây, con bò tót, con gấu đen, con công xanh, loài rắn có con mắt hồng ngọc, vượn má vàng vân vân….

Nhãn hiệu bảo vệ mà cơ quan UNESCO ban cấp không có xa lạ với sự mong muốn duy trì mãi mãi công viên này và khu rừng nhiệt đới của nó và khuyến khích chúng ta nên bảo tồn viên ngọc quý của thiên nhiên bằng mọi giá cho các thế hệ mai sau.

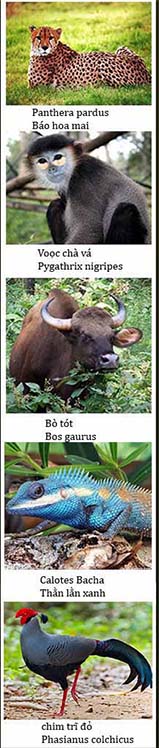

Malgré l’effort de reconnaître le parc national Cát Tiên comme la réserve de biosphère en novembre 2001 par l’UNESCO et le choix du rhinocéros de Java comme emblème du parc, les autorités vietnamiennes ne réussissent pas à sauvegarder le rhinocéros dont le dernier spécimen a été abattu par un braconnier en 2010. Cela montre à tel point qu’il est urgent de protéger ce parc. Celui-ci est la dernière forêt de plaine du Vietnam où il y a une biodiversité remarquable. La fragilité de cette forêt est due en grande partie à la déforestation massive liée à l’emploi des défoliants chimiques (agent orange) utilisés durant les années de guerre et aux développements économiques dont le Vietnam a besoin après sa réunification. On est passé de 48 millions d’habitants en 1975 à 97 millions environ en 2020. Le Vietnam devient l’un des pays les plus peuplés en Asie du Sud Est.

Malgré l’effort gouvernemental engagé dans sa politique de reboisement, cela ne suffit pas de sauver les forêts naturelles du Vietnam, en particulier celle du parc national Cát Tiên. D’abord, l’intérêt national ne trouve pas un écho favorable dans la population locale car celle-ci continue à utiliser le bois de la forêt comme matériau de construction et à grignoter les zones forestières en les transformant en plantations de caféier et d’anacardier sans parler de la dégradation provoquée habituellement par l’agriculture itinérante sur brûlis pratiquée par les minorités ethniques. Puis le reboisement ne permet pas de stopper la superficie totale des forêts primaires qui est passée de 3840 km2 à 800km2 seulement. De plus, on est habitué à gâcher la nature car on ne sait pas que celle-ci est indispensable à la vie et à la santé.

Le fait de tuer récemment un gaur vivant dans le parc Cát Tiên en octobre de l’année 2012 témoigne de ce méfait humain dû en grande partie à la pauvreté et à l’ignorance. L’homme a besoin de cette nature dont il n’est qu’un fragment. Il a intérêt de vivre en symbiose avec elle car il faut savoir que le maintien de la biodiversité est capital pour l’espèce humaine. Selon le biologiste français Gilles Bœuf, 50% des molécules actives utilisées en pharmacie proviennent des produits naturels ou des plantes. La forêt tropicale de Cát Tiên est un écosystème complexe dont l’équilibre est très fragile du fait qu’une zone d’habitation se trouve dans ce parc. De plus, le projet de réalisation de deux barrages hydrauliques en amont du lac des crocodiles sur le fleuve de Đồng Nai pourrait rompre cet équilibre et atteindre l’écosystème tout entier car les plantes et les animaux dépendent les uns des autres.

La sollicitation constante des espaces vitaux et des ressources constitue une menace grandissante et une forte pression sur la faune et la flore du parc. Il est difficile de chercher un juste équilibre pour l’environnement et pour les développements économiques. Mais il est dans notre intérêt de protéger ce parc Cát Tiên car c’est ici qu’on recense plus de 1.610 espèces végétales dont 38 inscrites dans le Livre Rouge, plus de 350 espèces d’oiseaux (nicheuses ou migratrices), 120 de reptiles et d’amphibiens, 105 de mammifères. On peut citer par exemple la panthère nébuleuse, le gaur, l’ours à collier, le paon spicifère (ou paon vert), la vipère aux yeux de rubis, le gibbon à joues jaunes etc. Le label de protection octroyé par l’UNESCO n’est pas étranger à sa volonté de vouloir pérenniser ce parc et sa forêt tropicale et de nous inciter à préserver à tout prix le joyau de la nature pour les générations futures.

In spite of the governemental effort for recognizing the national park Cát Tiên as the Biosphere Reserve in november 2001 by UNESCO and choosing Javan rhino as emblem of the park, Vietnamese authorities are not successful in protecting the rhino, the last specimen of which has been slaughtered by an poacher in 2010. It shows how urgent it is to protect this park. The latter is the last lowland forest of Vietnam where one finds a remarkable biodiversity. The weakness of this forest is caused largely by the massive deforestation (agent orange) related to the use of chemical defoliants during the years of war and economic developments required since the reunification of Vietnam. We have gone from 48 millions inhabitants in 1975 to 90 millions in 2010. Vietnam becomes the one of the most populous countries in Southeast Asia.

Despite the government effort used in his reforestation policy, that it is not enough to save natural forests of Vietnam, in particular that of Cát Tiên national park. Firstly, the national interest does not receive a favourable echo with the local people because the latter continues to use wood from the forest as a construction material and snacks forest areas by trasforming it in coffee and cashew plantations without evoking the degradation caused usually by the itinerant slash and burn agriculture of ethnic minorities. The reboisement cannot be successful in stopping the reduction of the total area of primary forests (from 3840 km2 to 800 km2). Moreover, one is accustomed to ruine the nature because one does not known that is essential for life and health. Recently, killing a gaur living Cát Tiên park in October 2012 testifies to this human mischief related largely to poverty and ignorance. Man needs this nature of which he is only a fragment. He is interested to live in symbiosis with her because one must known that the conservation of biodiversity is crucial for the human race. According to French biologist Gilles Bœuf, 50% active molecules used in pharmacies are collected from natural products and plants. The tropical forest Cát Tiên is a complex ecosystem, the balance of which is very fragile because one finds a living area in this park. In addition,the proposed realization of two hydraulic dams just upstream of crocodiles lake on Đồng Nai River, could break this balance and damage the entire ecosystem because plants and animals are dependent on one another.

The constant solicitation of living spaces and resources constitutes a growing threat and high pressure on wildlife and flora in the park. It is difficult to find a just balance for environment and economic developments. But it is in our interest to protect this park Cát Tiên because one identifies more 1610 plant species 38 of which are registered in the Red Book,more than 350 species of birds (nesting or migratory species), 120 reptiles and amphibians, 105 mammals. One can mention for example the clouded leopard, the gaur, the black bear, the green peacock, the viper with ruby eyes, the gibbon with yellow cheeks etc…. The label protection given by UNESCO is linked to its determination to sustain this park and its tropical forest and encourages us to preserve at all costs the nature jewel for future generations.

Grottes Tràng An

Hội An et ses quartiers (Sơ đồ các điểm tham quan ở Hội An)

Version française

English version

Chính ở đây chúng ta tìm thấy có rất nhiều các công trình kiến trúc nổi tiếng của thành phố Hội An. Được gọi là Minh An, khu này có m ột diện tích khoảng hai cây số vuông. Tương tự như các ô vuông được tìm thấy trên bàn cờ, các đường phố của nó rất ngắn và hẹp. Trong bản đồ này có 3 con đường ngang đó là đường Trần Phú, Nguyễn Thái Học và Bạch Đằng. Trong đó quan trọng nhất vẫn là đường Trần Phú kéo dài qua cầu Nhật Bản bằng đường Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai. Còn các phố dọc gồm có 5 phố: Nguyễn Huệ, Lê Lợi, Hoàng văn Thụ, Trần Quý Cáp và Hai Bà Trưng. Không có ngôi nhà nào có nhiều hơn một tầng. Việc xây dựng các nhà nầy được thực hiện bằng vật liệu truyền thống: gỗ và gạch.

Plan du quartier Minh An à Hôi An

Rue Trần Phú

- 7 Musée de l’histoire et de la culture

- 10 Siège de la congrégation du Hainan

- 14 Temple Minh Hương

- 24 Temple Guan Yu

- 46 Siège de la congrégation du Fujian

- 64 Siège des congrégations chinoises

- 77 Vieille maison Quân Thắng

- 80 Musée de la porcelaine et de la céramique

- 129 Vieille maison Đức An

- 149 Musée de la culture Sa Huỳnh

- 157 Siège de la congrégation du Chaozhou

- 176 Siège de la congrégation du Guangdong

- Pont pagode (Chùa cầu)

Rue Nguyễn Thái Học

- 33 Musée de folklore populaire (Bảo tàng văn hóa dân gian)

- 101 Vieille maison Tấn Ký (Nhà cổ Tấn Ký)

- Temple Hy Hòa (Miếu Hy Hòa)

Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai

Rue Lê Lợi

C’est ici qu’on trouve un grand nombre d’ouvrages architecturaux de renom de la ville Hội An. Etant connu sous le nom de Minh An, ce quartier possède une superficie d’environ deux kilomètres carrés. Analogues à des carrés qu’on trouve sur un échiquier, ses rues sont courtes et étroites. Dans ce plan, il y a trois axes de rues horizontales: Trần Phú, Nguyễn Thái Học et Bạch Đằng. La plus importante d’entre elles reste la rue Trần Phú prolongée au delà du pont japonais par la rue Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai. Quant aux rues verticales, on relève cinq: Nguyễn Huệ, Lê Lợi, Hoàng văn Thụ, Trần Quý Cáp et Hai Bà Trưng. Aucune maison n’a plus qu’un étage. Sa construction a été effectuée avec des matériaux traditionnels: bois et briques.

Here is where one finds a large number of renown architectural works of Hội An. Being known under the Minh An name, this neighborhood possesses an area of approximatively 2 square kilometers. Similar to squares found on a chess board, its streets are short and narrow. In this map, there are three axis of horizontal streets: Trần Phú, Nguyễn Thái Học and Bạch Đằng. The most important of these remains the Trần Phú street which is extended beyond the Japanese bridge by Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai street . As for vertical streets, there are five: Nguyễn Huệ, Lê Lợi, Hoàng văn Thụ, Hai Bà Trưng. No home has more than one floor. Its construction has been realized with traditional materials: wood and brick.

Références bibliographiques (Bibliography)

- Patrimoine mondial du Vietnam. Editions Thế Giới.

- World Heritage Hội An. Showa Women’s Univeristy Institute of International Culture (Japan).

- Hội An. Nguyễn văn Xuân. Maison d’édition Danang 2000

Quelques photos de ces maisons historiques

[Return HOI AN]

Hôi An sommaire (Première partie)

Première partie (Phần đầu)

Hội An a changé plusieurs fois de nom durant son histoire. Le nom « Hội An » suggère qu’à travers les mots (Hội= « Association ») et (An= »en paix ») cette ville devrait être un endroit où on pouvait se réunir en paix. Avant d’être sous le giron des seigneurs Nguyễn, Hội An se trouvait dans une région très développée du royaume du Champa du II ème au XIVème siècle. D’après la topographie, elle était au carrefour des fleuves venant du Nord (Cổ Cò, Vĩnh Điền) et du Sud (Trường Giang) que les bateaux de petite et moyenne taille avaient l’habitude d’emprunter fréquemment à cette époque pour atteindre la mer de l’Est à l’estuaire Cửa Đại (le Grand Estuaire). Elle était en quelque sorte le nœud de circulation favorisé par la nature et par la proximité des trois grands marais Trà Quế, Trà Nhiêu et Thi Lai, de l’ilôt Poulo-Cham ou Pulluciampelle (Cù Lao Chàm) et des estuaires Cửa Đại et Cửa Hàn. Selon certains historiens, la région Hội An servait du lieu d’approvisionnement des cités chames sacrées situées en amont: Mỹ Sơn et Trà Kiệu (Simhapura). Hội An était connue sous le nom de Lâm Ấp Phố. Son estuaire était désigné toujours comme celui du Grand Chămpa. (Cửa Đại Chiêm). En tout cas, elle jouait un rôle important en matière économique durant la période chame.

Les récentes fouilles archéologiques entamées par les chercheurs vietnamiens sur les anciens lieux d’habitation et sur les tombes antiques dans la zone de Hội An (Hậu Xá 1, Hậu Xá 2 (le long de rivière de Hội An), An Bằng, Thành Chiêm (commune Cẩm Hà), Xuân Lâm (Cẩm Phô) ont permis de réveler que cette agglomération fut autrefois une zone économique importante durant la période culturelle de Sa Huỳnh tardif car outre les cercueils en forme de jarre, on y a découvert des objets de fer datant de la dynastie des Han, des outils de travail et des bijoux qui sont autant de témoignages de l’existence d’un commerce florissant. Son nom a été cité maintes fois par les marchands chinois du temps où celle-ci relevait encore du Champa, ces derniers venant s’approvisionner du sel, d’or et de cannelle, marchandises de première nécessité en Chine.

Puis Hội An prospéra sous le nom de Hai Phố (Deux petits villages) au moment où le seigneur Nguyễn Hoàng du royaume Đại Việt installa son fils Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên (Seigneur Sãi) en tant que gouverneur de Quảng Nam en 1570. C’est la période brillante où Hội An connut un essor fulgurant dû en grande partie à la politique d’ouverture et d’immigration appropriée et clairvoyante menée par les seigneurs Nguyễn. Ceux-ci surent profiter de l’interdiction imposée par la Chine des Ming aux bateaux japonais, d’accoster sur ses côtes, pour les faire venir à Hội An où l’embargo chinois était moins efficace, du fait de la contrebande qui régnait en maître dans les provinces orientales de la Chine: Kouang Si, Fou Kien, Tsao Tcheou, Hainan. Dans le but d’accroître le commerce et les échanges avec les navires commerçants chinois, et encourager les grands bateaux de commerce japonais à se rendre en Asie du Sud Est (Thaïlande, Malaisie, Quảng Nam), le shogun Toyotomi mit en place un régime appelé « Permis à sceau royal » (le Shuinsen)(Châu Ấn Thuyền), une sorte d’autorisation tamponnée en rouge. Ces échanges, saisonniers et temporaires dans les premiers temps, se déroulaient habituellement sur des jonques ou sur le lieu de mouillage et de stationnement des bateaux de commerce, autour de la région de Trà Nhiêu. Cette pratique n’arrangea cependant pas certains marchands étrangers.

Tributaires de la période des moussons, du volume d’échange de marchandises vendues ou collectées et des saisons favorables à la navigation, ces derniers étaient contraints d’élire domicile à Hôi An et d’y rester plus longtemps que prévu, soit pour procéder à la réparation de leurs bateaux, soit pour saisir les opportunités d’acheter les marchandises et de les stocker, soit dans l’attente d’un moment favorable pour repartir en mer et éviter les tempêtes. C’est dans ce contexte que la ville Hội An fut fondée. Elle connut un développement galopant grâce aux facilités administratives octroyées aux étrangers par les seigneurs Nguyễn. Toute forme de résidence fut admise. C’est aussi à cette époque que Hội An accueillit les bateaux européens (portugais, hollandais, anglais et français), dont la venue favorisa non seulement l’établissement des comptoirs européens, mais aussi l’arrivée de missionnaires catholiques étrangers, parmi lesquels figurait le célèbre jésuite français Alexandre de Rhodes. Débarqué à Hội An en 1625, celui-ci commença à apprendre le vietnamien. Tellement doué au point de maîtriser rapidement la langue vietnamienne, il fut chargé, plus tard, de mettre au point la première transcription phonétique et romanisée de la langue vietnamienne, le Quốc ngữ (écriture nationale) (4). On ignore cependant si celui-ci eût le temps d’achever son œuvre à Hội An, car il n’y séjourna que trois années.

Par contre, on sait qu’il fut interdit de séjour à Quảng Nam en 1645 et que la parution de son dictionnaire vietnamo-portugais-latin eut lieu cinq ans après son expulsion. C’est sous le règne du seigneur Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên (Chúa Sãi) que furent créés, à Hội An, les quartiers communautaires (japonais, chinois, hollandais etc.). Chaque communauté avait son quartier où les habitants pouvaient vivre selon les us et coutumes de leur pays. L’administration de chaque quartier était assumée par un délégué des autorités locales. Hội An devenait ainsi l’un des ports commerciaux et centre économique de la Cochinchine, mais aussi, de l’Asie du Sud Est. La prospérité de Hội An ne faisait pas de doute. Dans sa compilation intitulée « Phủ Biên Tạp Lục » (Chroniques diverses de la frontière pacifiée), l’érudit vietnamien Lê Qúi Đôn en faisait état. Il y rapportait, notamment, les propos d’un commerçant chinois: « Les bateaux rentrant de Sơn Nam (1) (du Nord) ne ramènent que des cũ nâu (ignames sauvages ou Dioscorea cirrhosa) (2) et ceux de Thuận Hóa du poivre. Par contre, si on vient à Hội An, on peut y trouver tout». Le chercheur Trần Kinh Hoà, connu pour ses recherches sur Hội An, attribue à Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên le mérite d’avoir fondé Hội An. Il s’appuie, en cela, sur un passage du rapport du jésuite missionnaire Christoforo Borri sur les religions (en séjour à Nam Hà de 1618 à 1621). Le navigateur anglais William Adams relate également l’existence d’un quartier japonais en 1617.

Dans le passé, on pensait que ce quartier japonais était circonscrit au seul périmètre géographique de l’actuelle rue Trần Phú. Mais les dernières fouilles archéologiques ont mis à jour un grand nombre d’objets de céramique datant du 17è siècle (Chine, Japon et Vietnam) exhumés au- delà du pont-pagode japonais, dans la zone délimitée par le côté est de la rue Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai et le côté sud de la rue Phan Chu Trinh. Les résultats de ces fouilles permettent de se faire une idée plus précise aujourd’hui de la délimitation de ce quartier japonais, qui semble plus étendu qu’on ne l’imaginait au départ. Le temple Jomyo de Nagoya, au Japon, possède encore aujourd’hui une fresque picturale (Giao Chỉ Mậu Dịch Hải Đồ) datant de 1640, qui fait le récit du départ et de l’arrivée d’un bateau japonais (le Shuinsen) de Nagasaki à Hội An, après une navigation d’une quarantaine de jours en mer. Cette fresque picturale fut commandée à cette époque par la grande famille de commerçants japonais Chaya présente à Hội An durant la période 1615-1624. La communauté nippone commença à croître en même temps que l’agglomération d’Hội An. Les seigneurs Nguyễn favorisèrent le développement économique avec le Japon.

Outre l’argent, denrée très recherchée des Vietnamiens pour le développement de leur économie, le Japon put leur fournir de nombreux armements perfectionnés destinés à faire du Sud du Vietnam (Đàng Trong) un lieu de refuge sécurisé, à l’abri des attaques des Trịnh, sur le versant de la chaîne Hoành Sơn. On ne connaît pas avec exactitude la raison principale de ce rapprochement, mais on estime qu’au début du 17ème siècle, le nombre de Japonais vivant à Hội An était assez important pour permettre au seigneur Nguyễn de les recruter et former une unité de combat installée à l’estuaire Đại Chiêm, renommée pour ses talents et sa méthode de combat, sa loyauté et sa fidélité, à l’image des samouraïs japonais.

Un Japonais, du nom de Shutaro, qui réussit à gagner l’estime et l’affection du seigneur Nguyễn Phước Nguyên fut adopté par ce dernier et autorisé à prendre non seulement son nom de famille Nguyen, ainsi que son prénom, Đại Lương, mais aussi le titre de noblesse Hiển Hùng. Devenu, plus tard, le beau-fils du seigneur Nguyễn, il fut chargé de la gestion de Hội An. Il est probable que le pont-pagode japonais fut construit durant la période où Shutaro administrait cette ville. Mais à la suite d’une circulaire du Bakufu (Mạc Phủ Nhật) interdisant à ses concitoyens de partir à l’étranger, Shutaro dut rentrer subitement au Japon en même temps que sa femme, la princesse Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Hoa, dont le prénom japonais était Anio.

Suite à l’interdiction de pratiquer la religion catholique au Japon et à la persécution, par le seigneur Nguyễn Phúc Tần (Chúa Hiền), des catholiques japonais et chinois en 1664-1665 qui s’ensuivit, la communauté nippone commença à décliner rapidement à Hội An. Selon le commerçant britannique Thomas Bowyer, il ne restait plus, en 1695, que 4 ou 5 familles japonaises face à la communauté chinoise constituée d’environ 100 familles chinoises [BAVH, 1920,7ème année, n°2, p 200]. Au cours de son voyage dans la seigneurie des Nguyễn au cours de la même année, le célèbre bonze chinois Thích Đại Sán, dans son journal intitulé « Hải ngọai ký sự (Journal de voyage d’Outre-Mer »,1696) ne fait mention que d’un pont japonais terminant une rue chinoise (3) « bordée sans discontinuer de boutiques » et « longeant le fleuve », sans nullement évoquer la présence des Japonais. En dépit du retrait des Japonais à Hội An et de la politique d’isolationnisme menée au Japon, par le shogunat des Tokugawa, le commerce entre le Japon et le Vietnam ne prit pas fin pour autant. Celui-ci continua à fonctionner indirectement par l’intermédiaire des bateaux marchands chinois et hollandais, comme l’attestent les objets de céramique japonaise et vietnamienne datant du 17ème siècle retrouvés dans les sites de reliques vietnamiens, et ceux de Nagasaki, Sakai, Kyoto, qui sont la preuve irréfutable d’une continuité dans les échanges commerciaux entre ces deux pays. Aujourd’hui, aucun vestige architectural japonais sous forme de maisons et de pagodes ne subsiste à Hội An excepté le célèbre pont-pagode en bois qu’on est habitué à surnommer « le pont japonais » et quelques tombeaux éparpillés dans la région de Cẩm Châu.

Hội An sơ lược

Hôi An đã bao lần thay đổi tên trong lich sử. Qua hai chữ «Hội» và «An», tên nầy gợi ý cho chúng ta nghĩ đến một thành phố mà mọi người thích tựu hợp và sống an lành. Trước khi đựơc các chúa Nguyễn cai quảng, vùng đất nầy thuộc về vương quốc Chămpa và được phát triển từ thế kỷ thứ 2 đến thế kỷ 14. Theo địa hình, nó còn là ngã ba của các con sông đến từ phiá Bắc (Cổ Cò, Vĩnh Điện) và từ phía nam (Trường Giang) mà các thuyền bè nhỏ và trung bình thường hay lấy thời đó để ra biển Đông qua Cửa Đại. Nó còn được xem như là cái nút giao thông mà thiên nhiên ưu đãi vì nó ở gần các khu đầm lầy Trà Quế, Trà Nhiêu, Thị Lai và Cù lao Chàm.Theo các nhà sử gia, Hội An còn là nơi cung cấp lương thực, vật liệu cho các thành phố chàm nằm ở thượng lưu như Mỹ Sơn và Trà Kiệu. Hội An còn được biết dưới cái tên là “Lâm Ấp Phố” mà cửa sông thì vẫn được gọi là “cửa Đại Chiêm” vì Hội An giữ một vai trò rất quan trọng trên phương diện kinh tế trong thời kỳ Hội An còn thuộc về vương quốc Champa.

Chính vì vậy Hội An được bao lần nhắc đến bởi các thương gia Trung Hoa vì họ đến đây để mua muối, vàng, quế, các vật liệu cần thiết. Hội An lấy tên “Hai Phố” sau khi Nguyễn Hoàng bổ nhiệm Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên (chúa Sãi) làm tổng trấn ở Quảng Nam vào năm 1570. Chính trong thời kỳ nầy Hội An được phát triển mạnh mẽ nhờ có chính sách cởi mở, nhập cư thích hợp và sáng suốt của các chúa Nguyễn nhất là biết lợi dụng việc nghiêm cấm của triều đại Minh không cho các thuyền bè Nhật được cập bến các bờ biển Trung Hoa. Vì vậy Hội An trở thành nơi mà cấm vận không có hiệu quả chi cho mấy nhờ có buôn lậu thịnh hành ở các vùng nằm ở phiá đông của Trung Hoa như Hải Nam, Phước Kiến, Quảng Tây vân vân … Để tăng trưởng trao đổi hàng hoá với các thuyền bè người Hoa ở vùng Đông Nam Á (Thái Lan, Mã Lai, Quảng Nam), shogun Toyotomi cấp giấy phép thông hành có dấu triện đỏ (shuinjô) cho các thuyền bè Nhật có quyền mậu dịch, thường được gọi là Châu Ấn thuyền. Lúc đầu, các cuộc trao đổi hàng hóa thường ở trên thuyền hay là ở nơi mà các thuyền có thể cập bến, thông thường ở vùng Trà Nhiêu. Nhưng về sau, vì số lượng hàng hóa càng nhiều, gặp lúc mùa mưa hay là cần sửa chửa cần thiết khiến các thuyền cần phải đậu lại lâu dài ở Hội An hơn dự đoán để chờ những lúc thời tiết thuận lợi mà ra khơi quay về. Trong bối cảnh nầy, mới có sự thành hình của Hội An. Chính nhờ sự dễ dãi và mạnh dạn cho phép “Hoa di ngoại tộc” định cư mà Hội An trở thành nơi qui tụ dân tứ xứ, có cả các thuyền bè của châu Âu (Hoà Lan, Anh, Pháp và Bồ Đào Nha) cùng các tu sĩ công giáo trong đó có cha Đắc Lộ (Alexandre de Rhodes), một nguời đóng góp một phần quan trọng vào việc hình thành chữ quốc ngữ Việt Nam.

Dưới thời kỳ cai trị của chúa Sãi (Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên), Hội An rất được thịnh vượng và sầm uất với nhiều khu phố (Nhật, Trung Hoa, Hoà Lan vân vân….) Mỗi cộng đồng có một khu phố riêng tư với các tập quán của mình và có được một người đại biểu của chính quyền phụ trách. Hội An trở thành thời đó là một trong những hải cảng thương mại và trung tâm kinh tế của xứ Đàng Trong và Đông Nam Á. Trong cuốn Phủ biên tạp lục (1776), nhà học giả Lê Quí Đôn có miêu tả như sau: Thuyền từ Sơn Nam (Đàng Ngoài) về chỉ mua được một thứ củ nâu, thuyền từ Thuận Hóa (Phú Xuân) về cũng chỉ có một thứ là hồ tiêu. Còn từ Quảng Nam (Hội An) thì hàng hóa không thứ gì không có. Được nổi tiếng qua các công trình khảo cứu về Hội An, nhà nghiên cứu Trần Kinh Hoà nhận định rằng chúa Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên là người có công trạng thành lập Hôi An. Ông dựa trên một đọan viết trong tờ báo cáo của tu sĩ jésuite Christoforo Borri về các tôn giáo thời gian ông ở Nam Hà từ 1618 đến 1621. Nhà hàng hải người Anh William Adams có nhắc đến khu của người Nhật vào năm 1617. Trong quá khứ, ai cũng nghĩ rằng khu phố Nhật chỉ nằm vỏn vẹn ở chu vi của đường Trần Phú hiện nay. Nhưng với các khai quật khảo cổ gần đây, người ta tìm thấy một số hiện vật bằng gốm được xác định từ thế kỷ 17 (Trung Hoa, Nhật và Vietnam) thì nó nằm vượt qua khỏi chùa cầu trong khu vực giới hạn bởi phiá đông của đường Nguyễn Thị Minh khai và phiá nam của đường Phan Chu Trinh. Chính nhờ vậy người ta mới ấn định được phạm vi của khu Nhật ở Hội An, nó có phần rộng hơn dự kiến. Đền Jomyo ở Nagoya còn giữ cho đến hôm nay một bức tranh vẽ (Giao Chỉ Mậu Dịch Hải Đồ) từ 1640 kể lại cuộc hành trình của một châu ấn thuyền Nhật từ Nagasaki đến Hội An sau 40 ngày đi trên biển. Bích họa nầy được đặt làm ở thời đó bởi một gia đình Nhật Chaya có mặt ở Hội An từ năm 1615 đến 1624. Số người Nhật định cư bất đầu tăng lên cùng lúc với Hội An. Ngoài bạc ra, một thương phẩm mà người dân Việt rất cần trong việc phát triển kinh tế, Nhật Bản còn cung cấp vũ khí tối tân để biến Đàng Trong thành nơi nương náu an toàn để tránh các cuộc tấn công của chúa Trịnh qua sườn đồi của dãy Hoành Sơn. Không ai biết rỏ lý do của sự giao hảo thân thiện nầy nhưng có một điều là đầu thế kỷ thứ 17 số dân di cư người Nhật rất quan trọng cho đến đổi chúa Nguyễn chiêu mộ một đạo binh người Nhật chiếm đóng ở Cửa Đại vì họ nổi tiếng rất trung thực và giỏi về phương thức chiến đấu như các võ sĩ Nhật.

Có một người Nhật tên Shutaro được chúa Sãi yêu mến nhận làm con nuôi, gọi ông là Đại Lương và phong cho ông một huy hiệu qúi tộc Hiến Hùng. Sau nầy Đại Luơng không những là con rể của chúa Sãi mà còn là người quản lý Hội An. Rất có thể trong thời gian nầy mà chùa cầu được xây cất. Nhưng sau đó vì thông lệnh của Mạc Phủ (Bakufu) cấm người dân Nhật xuất ngoại, Shutaro buộc lòng cấp tốc trở về Nhật cùng vợ tức là công chúa Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Hoa mà tên Nhật là Anio. Sau việc cấm truyền bá đạo công giáo ở Nhật và chính sách ngược đãi của Nguyễn Phúc Tần (chúa Hiền) với các người công giáo Nhật và Hoa từ 1664 đến 1665, cộng đồng người Nhật ở Hội An bất đầu giảm dần. Theo thương gia người Anh Thomas Bowyer, chỉ còn ở Hội An 4 hay 5 gia đình vào 1695 so với cộng đồng người Hoa có khoảng chừng 100 gia đình. (BAVH 1920, năm thứ 7, số 2, trang 200). Cùng năm đó trong thời gian hành trình ở vùng đất chúa Nguyễn, một nhà sư nổi tiếng Thích Đại Sán có nhắc đến trong nhật ký của ông “Hải ngoại ký sự” cái cầu của người Nhật đuợc kết thúc với một con đường của người Hoa tràn đầy các tiệm buôn bán và dọc theo bờ sông mà chẳng nói chi về sự hiện diện của người Nhật. Mặc dầu có sự rút lui của người Nhật với chính sách biệt lập của Mạc phủ Tokugawa ở Nhật Bản, mậu dịch giữa chúa Nguyễn và Nhật Bản vẫn tiếp tục và không có bị gián đoạn nhờ các tàu Trung Hoa và Hòa Lan làm trung gian gián tiếp. Cụ thể còn tìm thấy các hiện vật bằng gốm của Nhật và Vietnam ở thế kỷ thứ 17 ở các nơi thánh tích của Vietnam và Nagasaki, Sakai, Kyoto của Nhật Bản. Ngày nay, không còn thấy dấu tích kiến trúc nào của người Nhật ngoài chùa cầu và vài mộ rải rác ở vùng Cẩm Châu.

English version

Hoi An Summary

First part (Phần đầu)

Hội An has changed its name several times throughout its history. The name « Hội An » suggests that through the words (Hội = « Association ») and (An = « peaceful »), this city should be a place where people could gather in peace. Before coming under the rule of the Nguyễn lords, Hội An was located in a highly developed region of the Champa kingdom from the 2nd to the 14th century. According to the topography, it was at the crossroads of rivers coming from the North (Cổ Cò, Vĩnh Điền) and the South (Trường Giang), which small and medium-sized boats frequently used at that time to reach the East Sea at the Cửa Đại estuary (the Great Estuary). It was, in a way, a traffic hub favored by nature and by the proximity of the three large marshes Trà Quế, Trà Nhiêu, and Thi Lai, the islet Poulo-Cham or Pulluciampelle (Cù Lao Chàm), and the estuaries Cửa Đại and Cửa Hàn. According to some historians, the Hội An region served as a supply point for the sacred Cham cities located upstream: Mỹ Sơn and Trà Kiệu (Simhapura). Hội An was known as Lâm Ấp Phố. Its estuary was always referred to as that of Greater Champa (Cửa Đại Chiêm). In any case, it played an important economic role during the Cham period.

Recent archaeological excavations undertaken by Vietnamese researchers at ancient habitation sites and antique tombs in the Hội An area (Hậu Xá 1, Hậu Xá 2 (along the Hội An river), An Bằng, Thành Chiêm (Cẩm Hà commune), Xuân Lâm (Cẩm Phô)) have revealed that this settlement was once an important economic zone during the late Sa Huỳnh cultural period. In addition to jar-shaped coffins, iron objects dating from the Han dynasty, working tools, and jewelry were discovered, all of which testify to the existence of a flourishing trade. Its name was mentioned many times by Chinese merchants when it was still part of Champa; these merchants came to procure salt, gold, and cinnamon, essential goods in China.

Then Hội An prospered under the name Hai Phố (Two small villages) at the time when Lord Nguyễn Hoàng of the Đại Việt kingdom installed his son Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên (Lord Sãi) as governor of Quảng Nam in 1570. This was a brilliant period when Hội An experienced a rapid boom largely due to the open and farsighted immigration policy carried out by the Nguyễn lords. They took advantage of the ban imposed by Ming China on Japanese ships from docking on its coasts, bringing them to Hội An where the Chinese embargo was less effective due to the smuggling that prevailed in the eastern provinces of China: Kouang Si, Fou Kien, Tsao Tcheou, Hainan. In order to increase trade and exchanges with Chinese merchant ships, and encourage large Japanese trading ships to come to Southeast Asia (Thailand, Malaysia, Quảng Nam), the shogun Toyotomi established a system called the « Royal Seal Permit » (the Shuinsen) (Châu Ấn Thuyền), a kind of authorization stamped in red. These exchanges, seasonal and temporary at first, usually took place on junks or at the anchorage and mooring sites of merchant ships around the Trà Nhiêu region. However, this practice did not please some foreign merchants.

Dependent on the monsoon season, the volume of traded goods sold or collected, and the seasons favorable for navigation, these traders were forced to settle in Hội An and stay longer than expected, either to repair their boats, seize opportunities to buy and store goods, or wait for a favorable moment to set sail again and avoid storms. It was in this context that the city of Hội An was founded. It experienced rapid development thanks to the administrative facilities granted to foreigners by the Nguyễn lords. All forms of residence were allowed. It was also during this period that Hội An welcomed European ships (Portuguese, Dutch, English, and French), whose arrival not only promoted the establishment of European trading posts but also the arrival of foreign Catholic missionaries, among whom was the famous French Jesuit Alexandre de Rhodes. Landing in Hội An in 1625, he began to learn Vietnamese. So talented that he quickly mastered the Vietnamese language, he was later tasked with developing the first phonetic and romanized transcription of the Vietnamese language, the Quốc ngữ (national script). However, it is unknown whether he had time to complete his work in Hội An, as he only stayed there for three years.

However, it is known that he was banned from residing in Quảng Nam in 1645 and that the publication of his Vietnamese-Portuguese-Latin dictionary took place five years after his expulsion. It was under the reign of Lord Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên (Chúa Sãi) that community quarters (Japanese, Chinese, Dutch, etc.) were created in Hội An. Each community had its own quarter where the inhabitants could live according to the customs and traditions of their country. The administration of each quarter was managed by a delegate of the local authorities. Hội An thus became one of the commercial ports and economic centers of Cochinchina, but also of Southeast Asia. The prosperity of Hội An was beyond doubt. In his compilation entitled « Phủ Biên Tạp Lục » (Miscellaneous Chronicles of the Pacified Frontier), the Vietnamese scholar Lê Qúi Đôn mentioned it. He notably reported the words of a Chinese merchant: « The boats returning from Sơn Nam (1) (the North) bring back only cũ nâu (wild yams or Dioscorea cirrhosa) (2) and those from Thuận Hóa bring pepper. However, if one comes to Hội An, one can find everything there. » The researcher Trần Kinh Hoà, known for his studies on Hội An, credits Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên with founding Hội An. He bases this on a passage from the report of the Jesuit missionary Christoforo Borri on religions (who stayed in Nam Hà from 1618 to 1621). The English navigator William Adams also mentions the existence of a Japanese quarter in 1617.

In the past, it was believed that this Japanese quarter was confined solely to the geographical perimeter of the current Trần Phú street. But recent archaeological excavations have uncovered a large number of ceramic objects dating from the 17th century (China, Japan, and Vietnam) unearthed beyond the Japanese pagoda bridge, in the area bounded by the east side of Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai street and the south side of Phan Chu Trinh street. The results of these excavations now allow for a more precise understanding of the boundaries of this Japanese quarter, which appears to be more extensive than initially imagined. The Jomyo temple in Nagoya, Japan, still possesses a pictorial fresco (Giao Chỉ Mậu Dịch Hải Đồ) dating from 1640, which narrates the departure and arrival of a Japanese ship (the Shuinsen) from Nagasaki to Hội An, after about forty days of sailing at sea. This pictorial fresco was commissioned at that time by the prominent Japanese merchant family Chaya, present in Hội An during the period 1615-1624. The Japanese community began to grow alongside the development of the Hội An settlement. The Nguyễn lords encouraged economic development with Japan.

Besides money, a highly sought-after commodity by the Vietnamese for the development of their economy, Japan was able to provide them with numerous advanced weapons intended to make South Vietnam (Đàng Trong) a secure refuge, protected from attacks by the Trịnh, on the Hoành Sơn mountain range side. The exact main reason for this alliance is not known, but it is believed that at the beginning of the 17th century, the number of Japanese living in Hội An was significant enough to allow the Nguyễn lord to recruit and train a combat unit stationed at the Đại Chiêm estuary, renowned for its skills and combat methods, loyalty, and fidelity, much like Japanese samurai.

A Japanese man named Shutaro, who succeeded in gaining the esteem and affection of Lord Nguyễn Phước Nguyên, was adopted by him and authorized not only to take his family name Nguyễn and the given name Đại Lương but also the noble title Hiển Hùng. Later becoming the lord Nguyễn’s son-in-law, he was entrusted with the management of Hội An. It is likely that the Japanese covered bridge was built during the period when Shutaro administered this city. However, following a circular from the Bakufu (Japanese Shogunate) prohibiting its citizens from traveling abroad, Shutaro had to abruptly return to Japan along with his wife, Princess Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Hoa, whose Japanese name was Anio.

Following the ban on practicing the Catholic religion in Japan and the persecution by Lord Nguyễn Phúc Tần (Chúa Hiền) of Japanese and Chinese Catholics in 1664-1665 that ensued, the Japanese community began to rapidly decline in Hội An. According to the British merchant Thomas Bowyer, by 1695, only 4 or 5 Japanese families remained compared to the Chinese community consisting of about 100 Chinese families [BAVH, 1920, 7th year, no. 2, p. 200]. During his journey through the Nguyễn lordship in the same year, the famous Chinese monk Thích Đại Sán, in his journal entitled « Hải ngọai ký sự (Overseas Travel Journal, 1696), » only mentions a Japanese bridge ending a Chinese street (3) « lined continuously with shops » and « running along the river, » without any mention of the presence of Japanese people. Despite the withdrawal of the Japanese in Hội An and the isolationist policy carried out in Japan by the Tokugawa shogunate, trade between Japan and Vietnam did not end. It continued to operate indirectly through Chinese and Dutch merchant ships, as evidenced by Japanese and Vietnamese ceramic objects dating from the 17th century found at Vietnamese relic sites, and those from Nagasaki, Sakai, Kyoto, which are irrefutable proof of continuity in commercial exchanges between these two countries.

Today, no Japanese architectural remains in the form of houses and pagodas survive in Hội An except for the famous wooden bridge-pagoda commonly referred to as « the Japanese bridge » and a few tombs scattered in the Cẩm Châu area.

BAVH: Bulletin des Amis du Vieux Huế

(1) Sơn Nam: la région du Nord englobant les provinces Nam Định et Thái Bình actuelles.

(2) très utilisés pour les teintures et les tannages des toiles et des filets de pêche au nord du Vietnam.

(3): Rue Trần Phú actuelle.

(4): Alexandre de Rhodes est l’auteur du Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum, dictionnaire trilingue vietnamien-portugais-latin édité à Rome en 1651 par la Congrégation pour l’évangélisation des peuples.

Hội An sommaire (3ème partie)

Troisième partie

Le paysage de la ville de Hội An commença à changer profondément vers le milieu du XVIIème siècle avec le départ forcé des Japonais et l’arrivée des Chinois. Le nom de la ville Hội An connu jusqu’alors sous le nom « Hai Phố (Deux villages) » n’avait plus la raison d’être avec la régression du quartier japonais. On donnait désormais à Hội An le nom traditionnel « Phố » (village ou rue) ou Hải Phố (village au bord de la mer) ou Hoa Phố (le village des Chinois). C’est probablement l’un de ces noms que les premiers missionnaires occidentaux ont traduit phonétiquement en Faifo. Mais sur la carte de Pieter Goos dessinée en 1666, on s’aperçoit qu’il y a un nom alternatif « Fayfoo » pour Hội An tandis que sur la carte d’Alexandre de Rhodes se trouve le mot « Haifo ». En tout cas, c’est le mot Faifo employé désormais par les Occidentaux pour désigner la ville Hội An. Le quartier japonais semble disparaître du paysage de la ville de Hội An car dans tous les récits tardifs des voyageurs étrangers (y compris celui du bonze libertin chinois Thích Đại Sán), on ne trouve aucun mot évoquant la présence japonaise.

Malgré cela, à travers l’adage des Hoianais, on sait qu’il existe au début de la fondation de Hội An deux quartiers, l’un japonais et l’autre chinois. Ce proverbe nous indique avec précision la délimitation de la ville : Thựơng chùa cầu, Hạ Âm Bổn. (En amont le pont-pagode, en aval le temple Âm Bổn). Le pont-pagode est situé à l’extrémité ouest de la ville tandis qu’à l’autre extrémité est se trouve le temple Âm Bổn du siège de la congrégation Triều Châu, dédié au grand général pacificateur de la mer, Ma Yuan (Mã Viện). C’est sur cet espace réduit qu’ont été construites les premières maisons traditionnelles chinoises sans étage, avec ou sans grenier (la rue Trần Phú actuelle). Mais aucune maison n’a réussi à résister aux dégradations et aux intempéries de la nature (pluie, inondation etc…) au fil des années. Grâce aux registres cadastraux anciens, on sait que la plus ancienne maison de la ville Hội An datant de 1738 est située actuellement au numéro3 de la rue Nguyễn Thi Minh Khai. La plupart des maisons traditionnelles visibles aujourd’hui à Hội An ont été ré-construites plusieurs fois sur les mêmes emplacements.

À côté de ce type de maison traditionnelle sans étage, on relève un autre type de modèle de maison chinoise très répandu dans la première moitié du XIXème siècle. C’est la maison avec étage dont la façade est en bois ou en brique. Étant de la même culture, ces émigrés chinois n’avaient aucun conflit religieux ou sérieux avec les Vietnamiens depuis leur installation. Par contre, cela leur permet de s’intégrer plus facilement dans la société vietnamienne et de devenir, grâce aux mariages mixtes, des Vietnamiens à part entière au renouvellement de quelques générations. Selon l’auteur Nguyễn Thiệu Lâu [BAVH, La formation et l’évolution du village Minh Hương(Faifo), 1941, Tome 4], la ville de Hội An était au début de son existence un « Minh Hương xã« , une commune habitée par une colonie chinoise. Grâce aux circonstances favorables dues au dot et aux dons des bienfaiteurs et bienfaitrices chinoises (1) et au colmatage de la berge du fleuve Thu Bồn, elle s’était agrandie progressivement pour devenir au fil des siècles un village de métis sino-vietnamien où ces émigrés chinois finissaient par être assimilés à la population locale.

Quant aux Hollandais, ils ne restaient pas inactifs car ils connaissaient très tôt Hội An. Leur Compagnie néerlandaise des Indes Orientales (*) établit au début de 1636 un comptoir à Hội An. Celui-ci cessa ses activités en 1641, l’année où l’exécution d’un voleur vietnamien par cette compagnie provoqua la colère du gouverneur Nguyễn Phước Tần. Celui-ci n’hésita pas prendre des mesures énergiques en brûlant toutes leurs marchandises saisies et en jetant à la mer tout le reste. De plus sept marchands hollandais furent exterminés lors de cet incident. La réaction hollandaise ne tarda pas à venir avec une confrontation armée quelques mois plus tard. Celle-ci dura de 1642 à 1643. Nguyễn Phúc Tần en sortit victorieux en détruisant la flotte hollandaise. L’amiral hollandais Peter Bach se donna la mort sur son bateau. C’est un exploit extraordinaire de combat naval entre les Occidentaux et le royaume du Sud des seigneurs Nguyễn car ces derniers réussirent à défaire pour la première fois la flotte européenne sur leur sol. Mais cela n’émoussa pas l’intention des Occidentaux de revenir plus tard au Vietnam dans le but de chercher des points d’appui militaire facilitant l’accès à la Chine et au commerce convoité depuis les débuts de l’époque moderne.

Entre-temps, Hội An connut à la fin du XVIIIème siècle des troubles provoqués par les révoltes paysannes, en particulier celle menée par les trois frères de Tây Sơn ( Nguyễn Nhạc, Nguyễn Lữ et Nguyễn Huệ) à Bình Định dans le centre du Vietnam. C’est la période où Hội An fut ravagée par l’invasion de l’armée nordiste des Trinh profitant du contexte troublant pour chasser les Nguyễn et combattre les Tây Sơn (Paysans de l’Ouest). En 1778, un commerçant britannique de nom Chapman, de passage à Hội An, fit la description suivante: Malgré l’aménagement réussi des quartiers avec des maisons en brique, il ne restait que des ruines. Malgré cela, Hội An reprit ses activités commerciales qui étaient loin d’être florissantes comme au début de sa fondation car la plupart des Chinois résidant à Hội An préférèrent de la quitter et de s’installer à Saïgon (Cholon). Celle-ci était en quelque sorte le bras allongé de Hội An. Puis vint un siècle plus tard le début de l’intervention militaire française prenant prétexte de la protection des missionnaires persécutés au Vietnam sous le règne de l’empereur Tự Đức (1858). C’était le début de la colonisation française au Vietnam.

À l’époque coloniale, Hội An continua à garder le nom de Faifo. Mais elle commença à prendre un autre visage, celui d’une ville européenne. Outre l’infrastructure moderne (équipement en eau, éclairage, canaux d’évacuation etc…), on y trouva la construction de nouveaux bâtiments publics dans le but de satisfaire les besoins de l’administration coloniale (l’hôtel de ville, le palais de justice, l’église etc…) et des maisons individuelles destinées à apporter le confort et bien-être aux fonctionnaires expatriés. Grâce à cet aménagement urbain, Hội An devint désormais une ville cosmopolite. Malgré cela, selon l’écrivain vietnamien Hữu Ngọc, Hội An fut délaissée très vite par les Français à cause de l’alluvion qui rendit difficile la navigation des bateaux sur le fleuve Thu Bồn. Ceux-ci préférèrent Tourane (ou Đà Nẵng) au détriment de Hội An vers la dernière moitié du XIXème siècle. Hội An tomba ainsi dans l’oubli car elle ne fut plus un centre économique et politique. Elle fut heureusement épargnée durant la guerre du Vietnam. C’est pour cette raison qu’elle peut conserver intact un grand nombre de vestiges architecturaux de grande valeur qui font aujourd’hui le bonheur des touristes vietnamiens et étrangers.

Une large part de son attrait réside sur le fait de nous laisser revivre le fil de son histoire à travers le temps.

Phần III

Cảnh quan Hội An bắt đầu thay đổi sâu sắc vào khoảng giữa thế kỷ 17 khi người Nhật Bản buộc phải rời đi và người Trung Quốc đến đây. Hội An không còn ý nghĩa Hai Phố vì phố Nhật không còn nửa. Từ đó, chỉ gọi Hội An là Hải Phố có nghĩa là Phố ở biển hay là Hoa Phố (phố của người Hoa). Có lẽ một trong hai tên nầy mà các cha cố đạo Âu Châu phát âm ra không rỏ mà thành Faifo. Tên nầy được giữ đến thời kỳ Pháp thuộc. Nhưng trên bản đồ của Pieter Goos vẽ năm 1666, chúng ta thấy Hội An có một tên gọi khác là « Fayfoo« , trong khi trên bản đồ của Alexander xứ Rhodes lại thấy chữ « Haifo« . Dù sao đi nữa, đó chính là chữ « Faifo » mà người phương Tây ngày nay dùng để chỉ Hội An. Khu phố Nhật Bản dường như biến mất khỏi cảnh quan Hội An bởi vì trong tất cả những ghi chép sau này của du khách nước ngoài (bao gồm cả nhà sư Trung Hoa phóng túng Thích Đại Sán), chúng ta không tìm thấy từ nào gợi lên sự hiện diện của người Nhật.

Mặc dù vậy, qua câu tục ngữ Hội An, chúng ta biết rằng khi Hội An mới thành lập, có hai quận, một của người Nhật và một của người Hoa. Câu tục ngữ này chỉ chính xác ranh giới của thành phố: Thượng chùa cầu, Hạ Âm Bổn. (Thượng nguồn cầu chùa, hạ nguồn chùa Âm Bổn). Cầu chùa nằm ở đầu phía tây của thành phố trong khi ở đầu phía đông còn lại là chùa Âm Bổn của trụ sở giáo đoàn Triều Châu, thờ vị tướng vĩ đại trấn an biển cả, Mã Viện. Chính trên không gian nhỏ bé này, những ngôi nhà truyền thống đầu tiên của người Hoa không có sàn, có hoặc không có gác xép (ngày nay là đường Trần Phú) đã được xây dựng. Nhưng không ngôi nhà nào có thể chịu được sự xuống cấp và thời tiết xấu của thiên nhiên (mưa, lũ lụt, v.v.) qua nhiều năm. Nhờ các hồ sơ địa chính cũ, chúng ta biết rằng ngôi nhà cổ nhất ở Thành phố Hội An, có niên đại từ năm 1738, hiện tọa lạc tại số 3 đường Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai. Hầu hết các ngôi nhà truyền thống hiện còn thấy ở Hội An đều đã được xây dựng lại nhiều lần trên cùng một địa điểm.

Bên cạnh kiểu nhà một tầng truyền thống này, còn có một kiểu nhà Trung Hoa khác rất phổ biến vào nửa đầu thế kỷ 19. Đây là kiểu nhà hai tầng với mặt tiền bằng gỗ hoặc gạch. Cùng chung một nền văn hóa, những người Hoa di cư này không có xung đột tôn giáo hay xung đột nghiêm trọng nào với người Việt Nam kể từ khi định cư. Mặt khác, điều này cho phép họ hòa nhập dễ dàng hơn vào xã hội Việt Nam và, nhờ hôn nhân khác chủng tộc, trở thành người Việt Nam chính thức sau vài thế hệ. Theo tác giả Nguyễn Thiệu Lâu [BAVH, Sự hình thành và phát triển của làng Minh Hương (Faifo), 1941, Tập 4], thành phố Hội An ban đầu là một « Minh Hương xã« , một xã có người Hoa sinh sống. Nhờ hoàn cảnh thuận lợi do của hồi môn và tiền quyên góp của các nhà hảo tâm người Hoa (1) và việc lấp bờ sông Thu Bồn, dần dần qua nhiều thế kỷ, nơi đây trở thành một ngôi làng có dòng máu lai Hoa-Việt, nơi những người Hoa di cư này đã hòa nhập vào dân cư địa phương.

Về phần người Hà Lan, họ không hề thụ động vì họ đã biết đến Hội An từ rất sớm. Công ty Đông Ấn Hà Lan (*) của họ đã thành lập một trạm buôn bán tại Hội An vào đầu năm 1636. Trạm này ngừng hoạt động vào năm 1641, năm mà việc công ty này hành quyết một tên trộm người Việt Nam đã khiến thống đốc Nguyễn Phước Tần tức giận. Ông không ngần ngại thực hiện các biện pháp mạnh mẽ bằng cách đốt cháy tất cả hàng hóa bị tịch thu và ném mọi thứ khác xuống biển. Ngoài ra, bảy thương gia Hà Lan đã bị tiêu diệt trong sự việc này. Phản ứng của người Hà Lan không lâu sau đó với một cuộc đối đầu vũ trang diễn ra vài tháng sau đó. Điều này kéo dài từ năm 1642 đến năm 1643. Nguyễn Phúc Tần đã giành chiến thắng bằng cách tiêu diệt hạm đội Hà Lan. Đô đốc người Hà Lan Peter Bach đã tự sát trên tàu của mình. Đây là một chiến công hải chiến phi thường giữa người phương Tây và vương quốc phía nam của các chúa Nguyễn, vì sau này đã thành công trong việc đánh bại hạm đội châu Âu trên lãnh thổ của họ lần đầu tiên. Nhưng điều này không làm giảm ý định quay trở lại Việt Nam sau này của người phương Tây để tìm kiếm chỗ đứng quân sự nhằm tạo điều kiện tiếp cận Trung Quốc và hoạt động thương mại mà họ đã thèm muốn từ đầu thời kỳ hiện đại.

Trong khi đó, Hội An đã trải qua tình trạng bất ổn vào cuối thế kỷ 18 do các cuộc khởi nghĩa nông dân gây ra, đặc biệt là cuộc khởi nghĩa do ba anh em nhà Tây Sơn (Nguyễn Nhạc, Nguyễn Lữ và Nguyễn Huệ) lãnh đạo ở Bình Định, miền Trung Việt Nam. Đây là thời kỳ Hội An bị tàn phá bởi cuộc xâm lược của quân đội Trịnh ở miền Bắc, lợi dụng bối cảnh bất ổn để đánh đuổi nhà Nguyễn và chống lại Tây Sơn (Nông dân miền Tây). Năm 1778, một thương nhân người Anh tên là Chapman, đi qua Hội An, đã mô tả như sau: Mặc dù các khu phố có nhà gạch đã phát triển thành công, nhưng chỉ còn lại những tàn tích. Mặc dù vậy, Hội An đã tiếp tục các hoạt động thương mại, vốn không hề thịnh vượng như lúc mới thành lập, vì hầu hết người Hoa sống ở Hội An thích rời khỏi đây và định cư ở Sài Gòn (Chợ Lớn). Theo một số cách, đây là cánh tay nối dài của Hội An. Sau đó, một thế kỷ sau, bắt đầu có sự can thiệp quân sự của Pháp với lý do bảo vệ các nhà truyền giáo bị đàn áp ở Việt Nam dưới thời vua Tự Đức (1858). Đây là sự khởi đầu của quá trình thực dân hóa Việt Nam của Pháp.

Trong thời kỳ thuộc địa, Hội An vẫn giữ tên Faifo. Nhưng nó bắt đầu mang một diện mạo khác, mang dáng dấp của một thành phố châu Âu. Bên cạnh cơ sở hạ tầng hiện đại (cấp nước, chiếu sáng, kênh thoát nước, v.v.), các công trình công cộng mới được xây dựng để đáp ứng nhu cầu của chính quyền thuộc địa (tòa thị chính, tòa án, nhà thờ vân vân) và nhà ở riêng lẻ được xây dựng để mang lại sự thoải mái và tiện nghi cho các quan chức xa xứ. Nhờ sự phát triển đô thị này, Hội An đã trở thành một thành phố quốc tế. Tuy nhiên, theo nhà văn Việt Nam Hữu Ngọc, người Pháp đã nhanh chóng bỏ rơi Hội An do phù sa khiến tàu thuyền khó di chuyển trên sông Thu Bồn. Họ ưa chuộng Tourane (hay Đà Nẵng) hơn là Hội An vào nửa cuối thế kỷ 19. Do đó, Hội An đã rơi vào quên lãng vì không còn là một trung tâm kinh tế và chính trị. May mắn thay, nó đã được bảo tồn trong Chiến tranh Việt Nam. Đây là lý do tại sao nơi đây có thể bảo tồn nguyên vẹn một số lượng lớn di tích kiến trúc có giá trị lớn mà ngày nay làm say mê du khách Việt Nam và nước ngoài.

Một phần lớn sức hấp dẫn của nó nằm ở chỗ cho phép chúng ta sống lại mạch truyện của nó theo thời gian.

Three part

The landscape of the city of Hội An began to change profoundly around the mid-17th century with the forced departure of the Japanese and the arrival of the Chinese. The name of the city Hội An, until then known as « Hai Phố (Two villages), » no longer made sense with the decline of the Japanese quarter. Hội An was now given the traditional name « Phố » (village or street) or Hải Phố (village by the sea) or Hoa Phố (the village of the Chinese). It is probably one of these names that the first Western missionaries phonetically translated as Faifo. But on the map by Pieter Goos drawn in 1666, one notices an alternative name « Fayfoo » for Hội An, while on Alexandre de Rhodes’s map, the word « Haifo » appears. In any case, it is the word Faifo now used by Westerners to designate the city of Hội An. The Japanese quarter seems to disappear from the landscape of the city of Hội An because in all later accounts of foreign travelers (including that of the libertine Chinese monk Thích Đại Sán), there is no mention of the Japanese presence.

Despite this, through the saying of the Hoianese, it is known that at the beginning of Hội An’s foundation there were two neighborhoods, one Japanese and the other Chinese. This proverb precisely indicates the boundaries of the city: Thượng chùa cầu, Hạ Âm Bổn. (Upstream the bridge-pagoda, downstream the Âm Bổn temple). The bridge-pagoda is located at the western end of the city while at the other eastern end is the Âm Bổn temple of the Triều Châu congregation, dedicated to the great general and pacifier of the sea, Ma Yuan (Mã Viện). It is in this small area that the first traditional Chinese houses without floors, with or without attics (the current Trần Phú street), were built. But no house has managed to withstand the damage and the harshness of nature (rain, flooding, etc.) over the years. Thanks to old cadastral records, it is known that the oldest house in Hội An, dating from 1738, is currently located at number 3 Nguyễn Thi Minh Khai street. Most of the traditional houses visible today in Hội An have been rebuilt several times on the same sites.

Next to this type of traditional single-story house, there is another type of Chinese house model that was very common in the first half of the 19th century. It is the house with an upper floor, whose facade is made of wood or brick. Being of the same culture, these Chinese emigrants had no religious or serious conflicts with the Vietnamese since their settlement. On the other hand, this allowed them to integrate more easily into Vietnamese society and, thanks to mixed marriages, to become full-fledged Vietnamese over the renewal of a few generations. According to the author Nguyễn Thiệu Lâu [BAVH, The formation and evolution of the Minh Hương village (Faifo), 1941, Volume 4], the city of Hội An was at the beginning of its existence a « Minh Hương xã, » a commune inhabited by a Chinese colony. Thanks to favorable circumstances due to dowries and donations from Chinese benefactors and benefactresses (1) and the filling in of the Thu Bồn riverbank, it gradually expanded over the centuries to become a Sino-Vietnamese mixed village where these Chinese emigrants eventually became assimilated into the local population.

As for the Dutch, they did not remain inactive because they knew Hội An very early on. Their Dutch East India Company (*) established a trading post in Hội An at the beginning of 1636. This post ceased its activities in 1641, the year when the execution of a Vietnamese thief by this company provoked the anger of Governor Nguyễn Phước Tần. He did not hesitate to take strong measures by burning all their seized goods and throwing the rest into the sea. Moreover, seven Dutch merchants were killed during this incident. The Dutch reaction was not long in coming, with an armed confrontation a few months later. This lasted from 1642 to 1643. Nguyễn Phúc Tần emerged victorious by destroying the Dutch fleet. The Dutch admiral Peter Bach took his own life on his ship. This was an extraordinary naval combat feat between the Westerners and the southern kingdom of the Nguyễn lords, as the latter succeeded in defeating the European fleet on their soil for the first time. But this did not dampen the Westerners’ intention to return later to Vietnam with the aim of seeking military footholds that would facilitate access to China and trade coveted since the beginning of the modern era.