Version vietnamienne

English version

Première partie (Phần đầu)

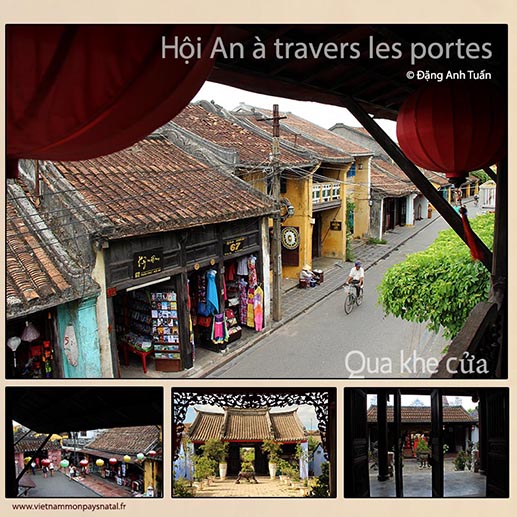

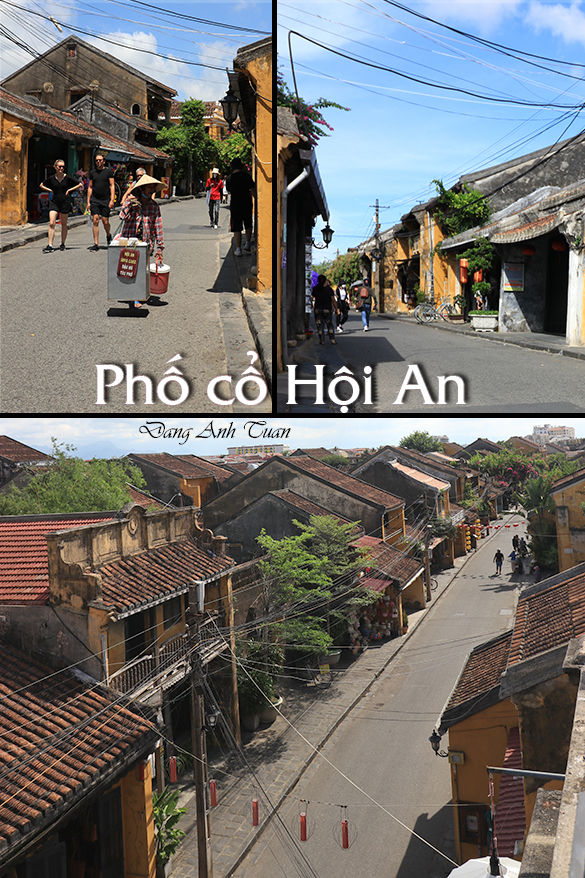

Hội An a changé plusieurs fois de nom durant son histoire. Le nom « Hội An » suggère qu’à travers les mots (Hội= « Association ») et (An= »en paix ») cette ville devrait être un endroit où on pouvait se réunir en paix. Avant d’être sous le giron des seigneurs Nguyễn, Hội An se trouvait dans une région très développée du royaume du Champa du II ème au XIVème siècle. D’après la topographie, elle était au carrefour des fleuves venant du Nord (Cổ Cò, Vĩnh Điền) et du Sud (Trường Giang) que les bateaux de petite et moyenne taille avaient l’habitude d’emprunter fréquemment à cette époque pour atteindre la mer de l’Est à l’estuaire Cửa Đại (le Grand Estuaire). Elle était en quelque sorte le nœud de circulation favorisé par la nature et par la proximité des trois grands marais Trà Quế, Trà Nhiêu et Thi Lai, de l’ilôt Poulo-Cham ou Pulluciampelle (Cù Lao Chàm) et des estuaires Cửa Đại et Cửa Hàn. Selon certains historiens, la région Hội An servait du lieu d’approvisionnement des cités chames sacrées situées en amont: Mỹ Sơn et Trà Kiệu (Simhapura). Hội An était connue sous le nom de Lâm Ấp Phố. Son estuaire était désigné toujours comme celui du Grand Chămpa. (Cửa Đại Chiêm). En tout cas, elle jouait un rôle important en matière économique durant la période chame.

Les récentes fouilles archéologiques entamées par les chercheurs vietnamiens sur les anciens lieux d’habitation et sur les tombes antiques dans la zone de Hội An (Hậu Xá 1, Hậu Xá 2 (le long de rivière de Hội An), An Bằng, Thành Chiêm (commune Cẩm Hà), Xuân Lâm (Cẩm Phô) ont permis de réveler que cette agglomération fut autrefois une zone économique importante durant la période culturelle de Sa Huỳnh tardif car outre les cercueils en forme de jarre, on y a découvert des objets de fer datant de la dynastie des Han, des outils de travail et des bijoux qui sont autant de témoignages de l’existence d’un commerce florissant. Son nom a été cité maintes fois par les marchands chinois du temps où celle-ci relevait encore du Champa, ces derniers venant s’approvisionner du sel, d’or et de cannelle, marchandises de première nécessité en Chine.

Puis Hội An prospéra sous le nom de Hai Phố (Deux petits villages) au moment où le seigneur Nguyễn Hoàng du royaume Đại Việt installa son fils Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên (Seigneur Sãi) en tant que gouverneur de Quảng Nam en 1570. C’est la période brillante où Hội An connut un essor fulgurant dû en grande partie à la politique d’ouverture et d’immigration appropriée et clairvoyante menée par les seigneurs Nguyễn. Ceux-ci surent profiter de l’interdiction imposée par la Chine des Ming aux bateaux japonais, d’accoster sur ses côtes, pour les faire venir à Hội An où l’embargo chinois était moins efficace, du fait de la contrebande qui régnait en maître dans les provinces orientales de la Chine: Kouang Si, Fou Kien, Tsao Tcheou, Hainan. Dans le but d’accroître le commerce et les échanges avec les navires commerçants chinois, et encourager les grands bateaux de commerce japonais à se rendre en Asie du Sud Est (Thaïlande, Malaisie, Quảng Nam), le shogun Toyotomi mit en place un régime appelé « Permis à sceau royal » (le Shuinsen)(Châu Ấn Thuyền), une sorte d’autorisation tamponnée en rouge. Ces échanges, saisonniers et temporaires dans les premiers temps, se déroulaient habituellement sur des jonques ou sur le lieu de mouillage et de stationnement des bateaux de commerce, autour de la région de Trà Nhiêu. Cette pratique n’arrangea cependant pas certains marchands étrangers.

Tributaires de la période des moussons, du volume d’échange de marchandises vendues ou collectées et des saisons favorables à la navigation, ces derniers étaient contraints d’élire domicile à Hôi An et d’y rester plus longtemps que prévu, soit pour procéder à la réparation de leurs bateaux, soit pour saisir les opportunités d’acheter les marchandises et de les stocker, soit dans l’attente d’un moment favorable pour repartir en mer et éviter les tempêtes. C’est dans ce contexte que la ville Hội An fut fondée. Elle connut un développement galopant grâce aux facilités administratives octroyées aux étrangers par les seigneurs Nguyễn. Toute forme de résidence fut admise. C’est aussi à cette époque que Hội An accueillit les bateaux européens (portugais, hollandais, anglais et français), dont la venue favorisa non seulement l’établissement des comptoirs européens, mais aussi l’arrivée de missionnaires catholiques étrangers, parmi lesquels figurait le célèbre jésuite français Alexandre de Rhodes. Débarqué à Hội An en 1625, celui-ci commença à apprendre le vietnamien. Tellement doué au point de maîtriser rapidement la langue vietnamienne, il fut chargé, plus tard, de mettre au point la première transcription phonétique et romanisée de la langue vietnamienne, le Quốc ngữ (écriture nationale) (4). On ignore cependant si celui-ci eût le temps d’achever son œuvre à Hội An, car il n’y séjourna que trois années.

Par contre, on sait qu’il fut interdit de séjour à Quảng Nam en 1645 et que la parution de son dictionnaire vietnamo-portugais-latin eut lieu cinq ans après son expulsion. C’est sous le règne du seigneur Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên (Chúa Sãi) que furent créés, à Hội An, les quartiers communautaires (japonais, chinois, hollandais etc.). Chaque communauté avait son quartier où les habitants pouvaient vivre selon les us et coutumes de leur pays. L’administration de chaque quartier était assumée par un délégué des autorités locales. Hội An devenait ainsi l’un des ports commerciaux et centre économique de la Cochinchine, mais aussi, de l’Asie du Sud Est. La prospérité de Hội An ne faisait pas de doute. Dans sa compilation intitulée « Phủ Biên Tạp Lục » (Chroniques diverses de la frontière pacifiée), l’érudit vietnamien Lê Qúi Đôn en faisait état. Il y rapportait, notamment, les propos d’un commerçant chinois: « Les bateaux rentrant de Sơn Nam (1) (du Nord) ne ramènent que des cũ nâu (ignames sauvages ou Dioscorea cirrhosa) (2) et ceux de Thuận Hóa du poivre. Par contre, si on vient à Hội An, on peut y trouver tout». Le chercheur Trần Kinh Hoà, connu pour ses recherches sur Hội An, attribue à Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên le mérite d’avoir fondé Hội An. Il s’appuie, en cela, sur un passage du rapport du jésuite missionnaire Christoforo Borri sur les religions (en séjour à Nam Hà de 1618 à 1621). Le navigateur anglais William Adams relate également l’existence d’un quartier japonais en 1617.

Dans le passé, on pensait que ce quartier japonais était circonscrit au seul périmètre géographique de l’actuelle rue Trần Phú. Mais les dernières fouilles archéologiques ont mis à jour un grand nombre d’objets de céramique datant du 17è siècle (Chine, Japon et Vietnam) exhumés au- delà du pont-pagode japonais, dans la zone délimitée par le côté est de la rue Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai et le côté sud de la rue Phan Chu Trinh. Les résultats de ces fouilles permettent de se faire une idée plus précise aujourd’hui de la délimitation de ce quartier japonais, qui semble plus étendu qu’on ne l’imaginait au départ. Le temple Jomyo de Nagoya, au Japon, possède encore aujourd’hui une fresque picturale (Giao Chỉ Mậu Dịch Hải Đồ) datant de 1640, qui fait le récit du départ et de l’arrivée d’un bateau japonais (le Shuinsen) de Nagasaki à Hội An, après une navigation d’une quarantaine de jours en mer. Cette fresque picturale fut commandée à cette époque par la grande famille de commerçants japonais Chaya présente à Hội An durant la période 1615-1624. La communauté nippone commença à croître en même temps que l’agglomération d’Hội An. Les seigneurs Nguyễn favorisèrent le développement économique avec le Japon.

Outre l’argent, denrée très recherchée des Vietnamiens pour le développement de leur économie, le Japon put leur fournir de nombreux armements perfectionnés destinés à faire du Sud du Vietnam (Đàng Trong) un lieu de refuge sécurisé, à l’abri des attaques des Trịnh, sur le versant de la chaîne Hoành Sơn. On ne connaît pas avec exactitude la raison principale de ce rapprochement, mais on estime qu’au début du 17ème siècle, le nombre de Japonais vivant à Hội An était assez important pour permettre au seigneur Nguyễn de les recruter et former une unité de combat installée à l’estuaire Đại Chiêm, renommée pour ses talents et sa méthode de combat, sa loyauté et sa fidélité, à l’image des samouraïs japonais.

Un Japonais, du nom de Shutaro, qui réussit à gagner l’estime et l’affection du seigneur Nguyễn Phước Nguyên fut adopté par ce dernier et autorisé à prendre non seulement son nom de famille Nguyen, ainsi que son prénom, Đại Lương, mais aussi le titre de noblesse Hiển Hùng. Devenu, plus tard, le beau-fils du seigneur Nguyễn, il fut chargé de la gestion de Hội An. Il est probable que le pont-pagode japonais fut construit durant la période où Shutaro administrait cette ville. Mais à la suite d’une circulaire du Bakufu (Mạc Phủ Nhật) interdisant à ses concitoyens de partir à l’étranger, Shutaro dut rentrer subitement au Japon en même temps que sa femme, la princesse Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Hoa, dont le prénom japonais était Anio.

Suite à l’interdiction de pratiquer la religion catholique au Japon et à la persécution, par le seigneur Nguyễn Phúc Tần (Chúa Hiền), des catholiques japonais et chinois en 1664-1665 qui s’ensuivit, la communauté nippone commença à décliner rapidement à Hội An. Selon le commerçant britannique Thomas Bowyer, il ne restait plus, en 1695, que 4 ou 5 familles japonaises face à la communauté chinoise constituée d’environ 100 familles chinoises [BAVH, 1920,7ème année, n°2, p 200]. Au cours de son voyage dans la seigneurie des Nguyễn au cours de la même année, le célèbre bonze chinois Thích Đại Sán, dans son journal intitulé « Hải ngọai ký sự (Journal de voyage d’Outre-Mer »,1696) ne fait mention que d’un pont japonais terminant une rue chinoise (3) « bordée sans discontinuer de boutiques » et « longeant le fleuve », sans nullement évoquer la présence des Japonais. En dépit du retrait des Japonais à Hội An et de la politique d’isolationnisme menée au Japon, par le shogunat des Tokugawa, le commerce entre le Japon et le Vietnam ne prit pas fin pour autant. Celui-ci continua à fonctionner indirectement par l’intermédiaire des bateaux marchands chinois et hollandais, comme l’attestent les objets de céramique japonaise et vietnamienne datant du 17ème siècle retrouvés dans les sites de reliques vietnamiens, et ceux de Nagasaki, Sakai, Kyoto, qui sont la preuve irréfutable d’une continuité dans les échanges commerciaux entre ces deux pays. Aujourd’hui, aucun vestige architectural japonais sous forme de maisons et de pagodes ne subsiste à Hội An excepté le célèbre pont-pagode en bois qu’on est habitué à surnommer « le pont japonais » et quelques tombeaux éparpillés dans la région de Cẩm Châu.

Lire_la_suite (Tiếp theo)

Version vietnamienne

Hội An sơ lược

Hôi An đã bao lần thay đổi tên trong lich sử. Qua hai chữ «Hội» và «An», tên nầy gợi ý cho chúng ta nghĩ đến một thành phố mà mọi người thích tựu hợp và sống an lành. Trước khi đựơc các chúa Nguyễn cai quảng, vùng đất nầy thuộc về vương quốc Chămpa và được phát triển từ thế kỷ thứ 2 đến thế kỷ 14. Theo địa hình, nó còn là ngã ba của các con sông đến từ phiá Bắc (Cổ Cò, Vĩnh Điện) và từ phía nam (Trường Giang) mà các thuyền bè nhỏ và trung bình thường hay lấy thời đó để ra biển Đông qua Cửa Đại. Nó còn được xem như là cái nút giao thông mà thiên nhiên ưu đãi vì nó ở gần các khu đầm lầy Trà Quế, Trà Nhiêu, Thị Lai và Cù lao Chàm.Theo các nhà sử gia, Hội An còn là nơi cung cấp lương thực, vật liệu cho các thành phố chàm nằm ở thượng lưu như Mỹ Sơn và Trà Kiệu. Hội An còn được biết dưới cái tên là “Lâm Ấp Phố” mà cửa sông thì vẫn được gọi là “cửa Đại Chiêm” vì Hội An giữ một vai trò rất quan trọng trên phương diện kinh tế trong thời kỳ Hội An còn thuộc về vương quốc Champa.

Chính vì vậy Hội An được bao lần nhắc đến bởi các thương gia Trung Hoa vì họ đến đây để mua muối, vàng, quế, các vật liệu cần thiết. Hội An lấy tên “Hai Phố” sau khi Nguyễn Hoàng bổ nhiệm Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên (chúa Sãi) làm tổng trấn ở Quảng Nam vào năm 1570. Chính trong thời kỳ nầy Hội An được phát triển mạnh mẽ nhờ có chính sách cởi mở, nhập cư thích hợp và sáng suốt của các chúa Nguyễn nhất là biết lợi dụng việc nghiêm cấm của triều đại Minh không cho các thuyền bè Nhật được cập bến các bờ biển Trung Hoa. Vì vậy Hội An trở thành nơi mà cấm vận không có hiệu quả chi cho mấy nhờ có buôn lậu thịnh hành ở các vùng nằm ở phiá đông của Trung Hoa như Hải Nam, Phước Kiến, Quảng Tây vân vân … Để tăng trưởng trao đổi hàng hoá với các thuyền bè người Hoa ở vùng Đông Nam Á (Thái Lan, Mã Lai, Quảng Nam), shogun Toyotomi cấp giấy phép thông hành có dấu triện đỏ (shuinjô) cho các thuyền bè Nhật có quyền mậu dịch, thường được gọi là Châu Ấn thuyền. Lúc đầu, các cuộc trao đổi hàng hóa thường ở trên thuyền hay là ở nơi mà các thuyền có thể cập bến, thông thường ở vùng Trà Nhiêu. Nhưng về sau, vì số lượng hàng hóa càng nhiều, gặp lúc mùa mưa hay là cần sửa chửa cần thiết khiến các thuyền cần phải đậu lại lâu dài ở Hội An hơn dự đoán để chờ những lúc thời tiết thuận lợi mà ra khơi quay về. Trong bối cảnh nầy, mới có sự thành hình của Hội An. Chính nhờ sự dễ dãi và mạnh dạn cho phép “Hoa di ngoại tộc” định cư mà Hội An trở thành nơi qui tụ dân tứ xứ, có cả các thuyền bè của châu Âu (Hoà Lan, Anh, Pháp và Bồ Đào Nha) cùng các tu sĩ công giáo trong đó có cha Đắc Lộ (Alexandre de Rhodes), một nguời đóng góp một phần quan trọng vào việc hình thành chữ quốc ngữ Việt Nam.

Dưới thời kỳ cai trị của chúa Sãi (Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên), Hội An rất được thịnh vượng và sầm uất với nhiều khu phố (Nhật, Trung Hoa, Hoà Lan vân vân….) Mỗi cộng đồng có một khu phố riêng tư với các tập quán của mình và có được một người đại biểu của chính quyền phụ trách. Hội An trở thành thời đó là một trong những hải cảng thương mại và trung tâm kinh tế của xứ Đàng Trong và Đông Nam Á. Trong cuốn Phủ biên tạp lục (1776), nhà học giả Lê Quí Đôn có miêu tả như sau: Thuyền từ Sơn Nam (Đàng Ngoài) về chỉ mua được một thứ củ nâu, thuyền từ Thuận Hóa (Phú Xuân) về cũng chỉ có một thứ là hồ tiêu. Còn từ Quảng Nam (Hội An) thì hàng hóa không thứ gì không có. Được nổi tiếng qua các công trình khảo cứu về Hội An, nhà nghiên cứu Trần Kinh Hoà nhận định rằng chúa Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên là người có công trạng thành lập Hôi An. Ông dựa trên một đọan viết trong tờ báo cáo của tu sĩ jésuite Christoforo Borri về các tôn giáo thời gian ông ở Nam Hà từ 1618 đến 1621. Nhà hàng hải người Anh William Adams có nhắc đến khu của người Nhật vào năm 1617. Trong quá khứ, ai cũng nghĩ rằng khu phố Nhật chỉ nằm vỏn vẹn ở chu vi của đường Trần Phú hiện nay. Nhưng với các khai quật khảo cổ gần đây, người ta tìm thấy một số hiện vật bằng gốm được xác định từ thế kỷ 17 (Trung Hoa, Nhật và Vietnam) thì nó nằm vượt qua khỏi chùa cầu trong khu vực giới hạn bởi phiá đông của đường Nguyễn Thị Minh khai và phiá nam của đường Phan Chu Trinh. Chính nhờ vậy người ta mới ấn định được phạm vi của khu Nhật ở Hội An, nó có phần rộng hơn dự kiến. Đền Jomyo ở Nagoya còn giữ cho đến hôm nay một bức tranh vẽ (Giao Chỉ Mậu Dịch Hải Đồ) từ 1640 kể lại cuộc hành trình của một châu ấn thuyền Nhật từ Nagasaki đến Hội An sau 40 ngày đi trên biển. Bích họa nầy được đặt làm ở thời đó bởi một gia đình Nhật Chaya có mặt ở Hội An từ năm 1615 đến 1624. Số người Nhật định cư bất đầu tăng lên cùng lúc với Hội An. Ngoài bạc ra, một thương phẩm mà người dân Việt rất cần trong việc phát triển kinh tế, Nhật Bản còn cung cấp vũ khí tối tân để biến Đàng Trong thành nơi nương náu an toàn để tránh các cuộc tấn công của chúa Trịnh qua sườn đồi của dãy Hoành Sơn. Không ai biết rỏ lý do của sự giao hảo thân thiện nầy nhưng có một điều là đầu thế kỷ thứ 17 số dân di cư người Nhật rất quan trọng cho đến đổi chúa Nguyễn chiêu mộ một đạo binh người Nhật chiếm đóng ở Cửa Đại vì họ nổi tiếng rất trung thực và giỏi về phương thức chiến đấu như các võ sĩ Nhật.

Có một người Nhật tên Shutaro được chúa Sãi yêu mến nhận làm con nuôi, gọi ông là Đại Lương và phong cho ông một huy hiệu qúi tộc Hiến Hùng. Sau nầy Đại Luơng không những là con rể của chúa Sãi mà còn là người quản lý Hội An. Rất có thể trong thời gian nầy mà chùa cầu được xây cất. Nhưng sau đó vì thông lệnh của Mạc Phủ (Bakufu) cấm người dân Nhật xuất ngoại, Shutaro buộc lòng cấp tốc trở về Nhật cùng vợ tức là công chúa Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Hoa mà tên Nhật là Anio. Sau việc cấm truyền bá đạo công giáo ở Nhật và chính sách ngược đãi của Nguyễn Phúc Tần (chúa Hiền) với các người công giáo Nhật và Hoa từ 1664 đến 1665, cộng đồng người Nhật ở Hội An bất đầu giảm dần. Theo thương gia người Anh Thomas Bowyer, chỉ còn ở Hội An 4 hay 5 gia đình vào 1695 so với cộng đồng người Hoa có khoảng chừng 100 gia đình. (BAVH 1920, năm thứ 7, số 2, trang 200). Cùng năm đó trong thời gian hành trình ở vùng đất chúa Nguyễn, một nhà sư nổi tiếng Thích Đại Sán có nhắc đến trong nhật ký của ông “Hải ngoại ký sự” cái cầu của người Nhật đuợc kết thúc với một con đường của người Hoa tràn đầy các tiệm buôn bán và dọc theo bờ sông mà chẳng nói chi về sự hiện diện của người Nhật. Mặc dầu có sự rút lui của người Nhật với chính sách biệt lập của Mạc phủ Tokugawa ở Nhật Bản, mậu dịch giữa chúa Nguyễn và Nhật Bản vẫn tiếp tục và không có bị gián đoạn nhờ các tàu Trung Hoa và Hòa Lan làm trung gian gián tiếp. Cụ thể còn tìm thấy các hiện vật bằng gốm của Nhật và Vietnam ở thế kỷ thứ 17 ở các nơi thánh tích của Vietnam và Nagasaki, Sakai, Kyoto của Nhật Bản. Ngày nay, không còn thấy dấu tích kiến trúc nào của người Nhật ngoài chùa cầu và vài mộ rải rác ở vùng Cẩm Châu.

Lire_la_suite (Tiếp theo)

English version

Hoi An Summary

First part (Phần đầu)

Hội An has changed its name several times throughout its history. The name « Hội An » suggests that through the words (Hội = « Association ») and (An = « peaceful »), this city should be a place where people could gather in peace. Before coming under the rule of the Nguyễn lords, Hội An was located in a highly developed region of the Champa kingdom from the 2nd to the 14th century. According to the topography, it was at the crossroads of rivers coming from the North (Cổ Cò, Vĩnh Điền) and the South (Trường Giang), which small and medium-sized boats frequently used at that time to reach the East Sea at the Cửa Đại estuary (the Great Estuary). It was, in a way, a traffic hub favored by nature and by the proximity of the three large marshes Trà Quế, Trà Nhiêu, and Thi Lai, the islet Poulo-Cham or Pulluciampelle (Cù Lao Chàm), and the estuaries Cửa Đại and Cửa Hàn. According to some historians, the Hội An region served as a supply point for the sacred Cham cities located upstream: Mỹ Sơn and Trà Kiệu (Simhapura). Hội An was known as Lâm Ấp Phố. Its estuary was always referred to as that of Greater Champa (Cửa Đại Chiêm). In any case, it played an important economic role during the Cham period.

Recent archaeological excavations undertaken by Vietnamese researchers at ancient habitation sites and antique tombs in the Hội An area (Hậu Xá 1, Hậu Xá 2 (along the Hội An river), An Bằng, Thành Chiêm (Cẩm Hà commune), Xuân Lâm (Cẩm Phô)) have revealed that this settlement was once an important economic zone during the late Sa Huỳnh cultural period. In addition to jar-shaped coffins, iron objects dating from the Han dynasty, working tools, and jewelry were discovered, all of which testify to the existence of a flourishing trade. Its name was mentioned many times by Chinese merchants when it was still part of Champa; these merchants came to procure salt, gold, and cinnamon, essential goods in China.

Then Hội An prospered under the name Hai Phố (Two small villages) at the time when Lord Nguyễn Hoàng of the Đại Việt kingdom installed his son Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên (Lord Sãi) as governor of Quảng Nam in 1570. This was a brilliant period when Hội An experienced a rapid boom largely due to the open and farsighted immigration policy carried out by the Nguyễn lords. They took advantage of the ban imposed by Ming China on Japanese ships from docking on its coasts, bringing them to Hội An where the Chinese embargo was less effective due to the smuggling that prevailed in the eastern provinces of China: Kouang Si, Fou Kien, Tsao Tcheou, Hainan. In order to increase trade and exchanges with Chinese merchant ships, and encourage large Japanese trading ships to come to Southeast Asia (Thailand, Malaysia, Quảng Nam), the shogun Toyotomi established a system called the « Royal Seal Permit » (the Shuinsen) (Châu Ấn Thuyền), a kind of authorization stamped in red. These exchanges, seasonal and temporary at first, usually took place on junks or at the anchorage and mooring sites of merchant ships around the Trà Nhiêu region. However, this practice did not please some foreign merchants.

Dependent on the monsoon season, the volume of traded goods sold or collected, and the seasons favorable for navigation, these traders were forced to settle in Hội An and stay longer than expected, either to repair their boats, seize opportunities to buy and store goods, or wait for a favorable moment to set sail again and avoid storms. It was in this context that the city of Hội An was founded. It experienced rapid development thanks to the administrative facilities granted to foreigners by the Nguyễn lords. All forms of residence were allowed. It was also during this period that Hội An welcomed European ships (Portuguese, Dutch, English, and French), whose arrival not only promoted the establishment of European trading posts but also the arrival of foreign Catholic missionaries, among whom was the famous French Jesuit Alexandre de Rhodes. Landing in Hội An in 1625, he began to learn Vietnamese. So talented that he quickly mastered the Vietnamese language, he was later tasked with developing the first phonetic and romanized transcription of the Vietnamese language, the Quốc ngữ (national script). However, it is unknown whether he had time to complete his work in Hội An, as he only stayed there for three years.

However, it is known that he was banned from residing in Quảng Nam in 1645 and that the publication of his Vietnamese-Portuguese-Latin dictionary took place five years after his expulsion. It was under the reign of Lord Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên (Chúa Sãi) that community quarters (Japanese, Chinese, Dutch, etc.) were created in Hội An. Each community had its own quarter where the inhabitants could live according to the customs and traditions of their country. The administration of each quarter was managed by a delegate of the local authorities. Hội An thus became one of the commercial ports and economic centers of Cochinchina, but also of Southeast Asia. The prosperity of Hội An was beyond doubt. In his compilation entitled « Phủ Biên Tạp Lục » (Miscellaneous Chronicles of the Pacified Frontier), the Vietnamese scholar Lê Qúi Đôn mentioned it. He notably reported the words of a Chinese merchant: « The boats returning from Sơn Nam (1) (the North) bring back only cũ nâu (wild yams or Dioscorea cirrhosa) (2) and those from Thuận Hóa bring pepper. However, if one comes to Hội An, one can find everything there. » The researcher Trần Kinh Hoà, known for his studies on Hội An, credits Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên with founding Hội An. He bases this on a passage from the report of the Jesuit missionary Christoforo Borri on religions (who stayed in Nam Hà from 1618 to 1621). The English navigator William Adams also mentions the existence of a Japanese quarter in 1617.

In the past, it was believed that this Japanese quarter was confined solely to the geographical perimeter of the current Trần Phú street. But recent archaeological excavations have uncovered a large number of ceramic objects dating from the 17th century (China, Japan, and Vietnam) unearthed beyond the Japanese pagoda bridge, in the area bounded by the east side of Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai street and the south side of Phan Chu Trinh street. The results of these excavations now allow for a more precise understanding of the boundaries of this Japanese quarter, which appears to be more extensive than initially imagined. The Jomyo temple in Nagoya, Japan, still possesses a pictorial fresco (Giao Chỉ Mậu Dịch Hải Đồ) dating from 1640, which narrates the departure and arrival of a Japanese ship (the Shuinsen) from Nagasaki to Hội An, after about forty days of sailing at sea. This pictorial fresco was commissioned at that time by the prominent Japanese merchant family Chaya, present in Hội An during the period 1615-1624. The Japanese community began to grow alongside the development of the Hội An settlement. The Nguyễn lords encouraged economic development with Japan.

Besides money, a highly sought-after commodity by the Vietnamese for the development of their economy, Japan was able to provide them with numerous advanced weapons intended to make South Vietnam (Đàng Trong) a secure refuge, protected from attacks by the Trịnh, on the Hoành Sơn mountain range side. The exact main reason for this alliance is not known, but it is believed that at the beginning of the 17th century, the number of Japanese living in Hội An was significant enough to allow the Nguyễn lord to recruit and train a combat unit stationed at the Đại Chiêm estuary, renowned for its skills and combat methods, loyalty, and fidelity, much like Japanese samurai.

A Japanese man named Shutaro, who succeeded in gaining the esteem and affection of Lord Nguyễn Phước Nguyên, was adopted by him and authorized not only to take his family name Nguyễn and the given name Đại Lương but also the noble title Hiển Hùng. Later becoming the lord Nguyễn’s son-in-law, he was entrusted with the management of Hội An. It is likely that the Japanese covered bridge was built during the period when Shutaro administered this city. However, following a circular from the Bakufu (Japanese Shogunate) prohibiting its citizens from traveling abroad, Shutaro had to abruptly return to Japan along with his wife, Princess Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Hoa, whose Japanese name was Anio.

Following the ban on practicing the Catholic religion in Japan and the persecution by Lord Nguyễn Phúc Tần (Chúa Hiền) of Japanese and Chinese Catholics in 1664-1665 that ensued, the Japanese community began to rapidly decline in Hội An. According to the British merchant Thomas Bowyer, by 1695, only 4 or 5 Japanese families remained compared to the Chinese community consisting of about 100 Chinese families [BAVH, 1920, 7th year, no. 2, p. 200]. During his journey through the Nguyễn lordship in the same year, the famous Chinese monk Thích Đại Sán, in his journal entitled « Hải ngọai ký sự (Overseas Travel Journal, 1696), » only mentions a Japanese bridge ending a Chinese street (3) « lined continuously with shops » and « running along the river, » without any mention of the presence of Japanese people. Despite the withdrawal of the Japanese in Hội An and the isolationist policy carried out in Japan by the Tokugawa shogunate, trade between Japan and Vietnam did not end. It continued to operate indirectly through Chinese and Dutch merchant ships, as evidenced by Japanese and Vietnamese ceramic objects dating from the 17th century found at Vietnamese relic sites, and those from Nagasaki, Sakai, Kyoto, which are irrefutable proof of continuity in commercial exchanges between these two countries.

Today, no Japanese architectural remains in the form of houses and pagodas survive in Hội An except for the famous wooden bridge-pagoda commonly referred to as « the Japanese bridge » and a few tombs scattered in the Cẩm Châu area.

Reading more (Tiếp theo)

BAVH: Bulletin des Amis du Vieux Huế

(1) Sơn Nam: la région du Nord englobant les provinces Nam Định et Thái Bình actuelles.

(2) très utilisés pour les teintures et les tannages des toiles et des filets de pêche au nord du Vietnam.

(3): Rue Trần Phú actuelle.

(4): Alexandre de Rhodes est l’auteur du Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum, dictionnaire trilingue vietnamien-portugais-latin édité à Rome en 1651 par la Congrégation pour l’évangélisation des peuples.