First part

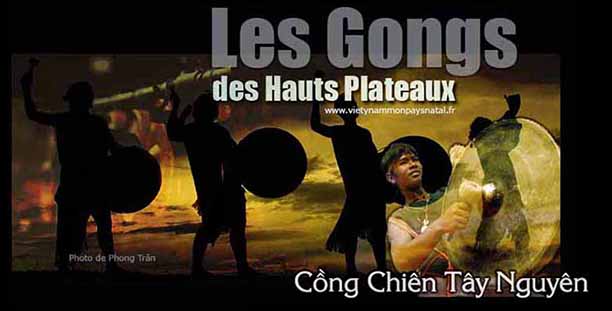

Since the dawn of time, the gong culture is the preferred approach used by the populations of the Central Highlands (Vietnam) living from agriculture in communication with the spirit world. According to their shamanistic and animist beliefs, the gong is a sacred instrument because it secretly houses a genius supposed to protect not only the owner but also his family, his clan and his village. Its âge not only improves its sound but also the power and magical potency of the occupier genius. In addition, the gong will acquire a special patina over the years. This percussion instrument cannot be considered as an standard musical instrument. It is present at all the important occasions of the village. It is inseparable from the social life of highland tribes. The newborn baby is invited to listen the sound of the gong played by the elder village from the first month of his birth, which allows him to recognize the voice of his tribe and his clan. He become now an element of his ethnic community. Then he grows over years to the rhythm of gong sound which carries him away with the fermented rice alcohol (rượu cần) in the evening meetings around a jar and fire and in the village festivals (offerings, marriages, funeral, celebrations of the new years’s day or the victory, inauguration of the new housing, family reunion, agricultural ritual (paddy germination, ear initiation, feast of the agricultural close etc …). Finally, at his death, he is accompagnied by the rolling of the gongs to the burial with solemnity.

© Đặng Anh Tuấn

According to the Edê, a life without gong is a life without rice and salt. Each family must have at least a gong because this instrument proves not only its fortune but also with its authority and prestige in its ethnic community and its region. In function of each village, the set of instruments can be simply represented by two gongs but you can find sometimes up to 9, 12, 15 or 20 gongs. Each of these is called by a name that indicates its position in a hierarchy similar to that found in a matriarchal family. According to French ethnomusicologist Patrick Kersale, the gongs reflect the image of the family structure with matrilineal inflection. For the Chu Ru, there are three gongs in a set. (Gong-mother, gong-aunt and gong-daughter). By contrast, for the Ê Đê Bih , the set of gongs consists of three pairs of gongs. The first pair is called under the name of gongs grand-mothers. And then the second pair is reserved for the gong-mothers and the last pair is for the gong-daughters.

In addition, there is a drum played by the oldest person to give the tempo. For peoples living in the south of the Highlands, there are also 6 gongs in a set but the gong-mother (chiền mẹ) remains the most important and is maintained slighty in the lower position compared with the other gongs. It is always accompanied by the gong-father followed then by the gong-children and gong-grandchildren. Due to their large size, the two gongs mother and father produce low sounds and nearly identical, which allows them to serve as a constituent basis to the orchestra.

In speculating about the provenance of gongs,we note they are found not only in India but also in China and in the region of Southeast Asia. Despite their mention in the Chinese inscriptions around the year 500 after Jesus Christ (period of Đồng Sơn civilization), there is a tendency to attribute to the Southeast Asia region their origin because the gong culture embraces only the regions where live Austro-asiatic and Austronesian peoples. (Vietnam, Kampuchea, Thailand, Myanmar, Java, Bali, Mindanao (Philippines) etc …). According to some Vietnamese scholars, the gongs are linked closely to the the aquatic rice cultivation. For the Vietnamese researcher Trần Ngọc Thêm, the gongs are used to imitate the noise of thunder. They have a sacred role in the annual ceremonies of rain making rituals, with the aim of having a good harvest. In addition, we find in these gongs an intimate binding with the Đồng Sơn culture because the gongs were present visibly on some bronze drums (Ngọc Lữ for example). The gongs had to be considered a sacred instrument in ritual celebrations so that they were honored by the Dongsonian on their drums. Among the Mường who are « close cousins » to the Vietnamese, one continues to associate the bonze drums (character Yang) with the gongs (character yin) which the Mường still regard as a stylized representation of the woman chest in religious festivals. These gongs are in some way the symbol of fertility. According to the Vietnamese musician Tô Vũ, the Mường forced back in the inaccessible mountainous regions, could continue to keep carefully these gongs against the Chinese conquerors. This is not the case of the Dongsonian (the ancestors of the Vietnamese) during the Chinese conquest led by the general Ma Yuan (or Mã Viện) of West Han dynasty after the sisters Trưng Trắc and Trưng Nhị revolt. More reading (Tiếp theo)

Bibliographic references

- Recherche de l’identité de la culture vietnamienne. Trần Ngọc Thêm, Editions Thế Giới,Hànôi 2008

- Les Mnong des hauts-plateaux, Centre-Vietnam: Vie matérielle. Albert-Marie Maurice, Tome 1, Editeur L’Harmattan. 1993 Cồng chiêng Tây Nguyên. Di sản phi vật thể thế giơí. Trần Văn Khê. Vietsciences, 01/01/2006.

- Vài nẻt đặc thù của cồng chiêng Tây Nguyên. Giáo Sư Trần Văn Khê. 2009

- Người ÊĐê ở Việt Nam. The Ede in Vietnam. Editeur Thông Tấn 2010

- La chanson de Damsan. Légende recueillie chez les Rhade de la province de Darlac. Texte et traduction. Louis Sabatier. BEFEO, 1933, Tome 33, n°33, pp: 143-302

- Tranh luận về cồng chiêng Tây Nguyên. SGTT 2012

- Sur l’origine géographique des langues Viet Muong. Michel Fergus, Môn Khmer Studies, 18-19: 52-59

- Độc Đáo cồng chiêng Tây Nguyên. Bùi Trọng Hiền. Nguyễn Quang Vinh Tạp chí Ngày Nay. 28/02/2011

- Gongs de tous les pouvoirs. DVD documentaire de Patrick Kersalé.2009