L’oiseau Lạc est -il l’oiseau totémique des Proto-Vietnamiens?

Chim Lạc có phải vật tổ của người dân Việt không ?

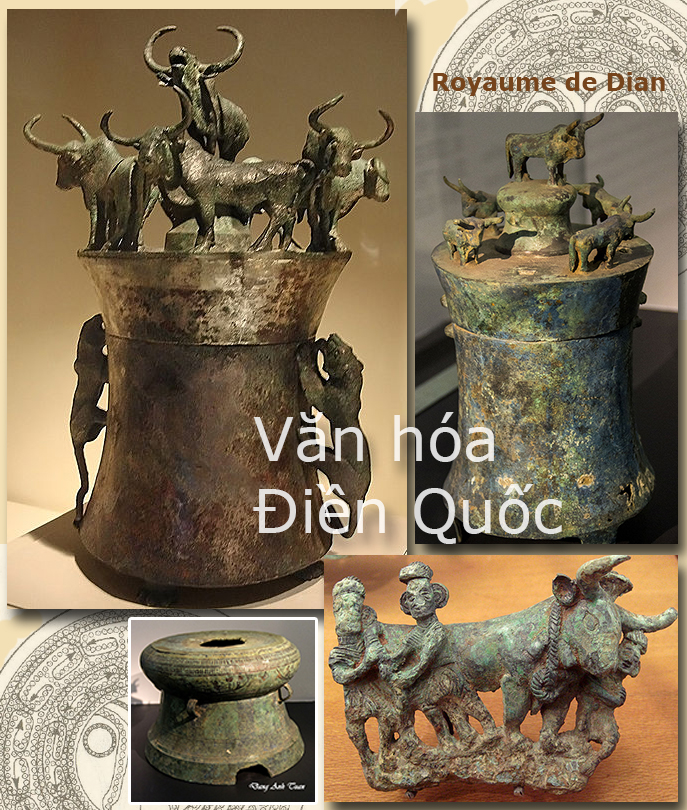

Câu hỏi nầy thường được nêu ra sau thời kỳ các nhà khảo cổ học thuộc Trường Viễn Đông Bác cổ Pháp (Louis Pajot, Olov Jansen) phát hiện ra một số đồ đồng cổ ở thung lũng Mã, đặc biệt là ở làng Đồng Sơn (Thanh Hóa) vào năm 1924. Sau đó với sự đề xuất của nhà khảo cổ học ngừời Áo R. Heine-Geldern thì văn hóa này được gọi là « Văn hóa Ðồng Sơn » tức là văn hóa của người Việt cổ.

Ngoài việc tranh dành về nguồn gốc trống đồng giữa hai nước Việt Nam và Trung Hoa, còn có thêm cuộc tranh luận về các hình tượng trang trí được thấy nhiều trên mặt trống đồng nhất là con chim chi không biết là loại chim gì chân cao mỏ dài trong tư thế bay hay ngồì. Học giả Đào Duy Anh đã ngộ nhận và kết luận trong quyển Lịch sử cổ đại Việt Nam rằng đây là con chim lạc chỉ một loại hậu điểu tương tự như ngỗng trời là vật tổ của người Lạc Việt. Thưở xưa, các thị tộc ở xã hội nguyên thủy hay thường lấy tên thị tộc mà đặt tên cho vật tổ tức là con chim lạc. Nhưng dù thuyết vật tổ của ông là lý thuyết sai lầm theo sư nhận xét của sử gia Trần Gia Phụng hay nhà văn Đinh Hồng Hải nhưng vì ông là một trong những học giả uyên thâm hàng đầu Việt Nam ở thời đó nên dễ thuyết phục dư luận. Sự nhận định nầy khiến ít ai dám phủ nhận cả mà còn tạo ra một ý niệm về mối quan hệ mật thiết giữa người Lạc Việt và loài chim nầy. Rồi ý niệm nầy trở thành từ đó quan niệm chim Lạc, vật tổ của người Lạc Việt. Theo sử gia Trần Gia Phụng tất cả tài liệu có nói đến chữ Lạc như Thủy kinh chú của Lịch Đạo Nguyên (thế kỷ thứ 6) hay An Nam chí lược của Lê Tắc (thế kỷ 13) đều dựa trên sách cổ « Giao Châu ngoại vực ký » của Trung Hoa được xuất hiện khoảng giữa đời nhà Tấn (265-420) trong đó có một đoạn văn viết như sau: Giao Chỉ tích hữu quận huyện chi thời, thổ địa hữu lạc điền. Kỳ điền tòng thủy triều thượng hạ. Dân khẩn thực kỳ điền, nhân các vị Lạc dân, thiết Lạc vương, Lạc hầu chủ chư quận huyện. Đa vi Lạc tướng, đồng ấn thanh thụ. Xưa, khi Giao Chỉ chưa thành quận huyện, đất đai có ruộng gọi là ruộng lạc, ruộng đó tùy thủy triều lên xuống mà làm. Dân khẩn ruộng đó mà ăn, vì thế tất cả gọi là dân Lạc. Họ lập Lạc vương, Lạc hầu để coi quận huyện. Có nhiều Lạc tướng, có ấn đồng lụa xanh.

Chữ Lạc đọc ở trên đây theo âm Hán Việt chớ người Hoa họ đọc theo âm Trung Hoa thì là « lo, ló, lô » như thành Lạc Dương thủ đô nhà Châu thì được phiên âm theo chữ Latin ra là Loyang. Như vây chữ có âm « lo, ló, lô » trong tiếng Việt cổ là gì ? Nó chỉ là lúa gạo. Bởi vậy từ Thừa Thiên đến Nghệ An, mọi người hay thường dùng chữ ló để ám chỉ lúa. Tại vùng Quảng Bình ở miền trung mới có câu tục ngữ « Cơm mô cho vừa bụng chó, ló mô cho vừa bụng gà». Như vậy chữ Lạc là từ ngữ phát âm theo lối Hán Việt chớ chữ Lạc mà cố tìm sự giải thích nào khác cũng hoàn toàn vô nghĩa vì nó không phải là chữ phiên âm từ tiếng của người Việt cổ. Có thể nói chữ Lạc mà tìm hiểu nghĩa theo chữ Trung hoa thì sẽ bị lạc hướng. Người Hoa dùng chữ Lạc đễ phiên âm tiếng Ló của người Giao Chỉ và để chỉ tộc người có nền văn minh lúa nước.

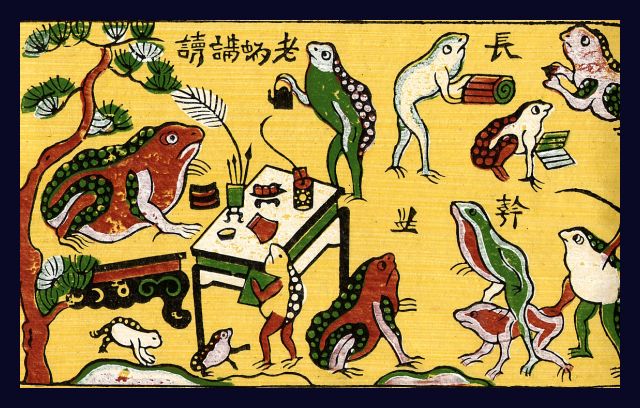

Bởi vậy bất cứ chữ Lạc nào với bất cứ bộ thủ nào, họ cũng đọc là Lo cả theo sự nhận xét của cố học giả Hoàng Văn Chí trong sách Duy văn sử quan. Ngày nay có nhiều dân tộc miền núi hay nhiều điạ phương ở nước ta vẫn còn dùng từ ngữ ló để nói lúa gạo như Hà Tĩnh, Nghệ An, Quảng Bình hay từ ngữ lọ ở Thanh Hóa. Còn người Mường thì gọi với một âm tiết khá nặng giữa chữ lỏ và lọ (như cơm mường vó, lọ mường vang) (Đinh Hồng Hải, trang 72). Như vậy con chim Lạc là con chim không có thật sự trong môi trường thiên nhiên ở đất nước ta. Nó cũng không có ghi chú trong các từ điển của nước ta để ám chỉ con chim lạc cả. Nó không phải là con vật tổ của người Việt cổ thì nếu không nó được nằm ở vị trí trung tâm của mặt trống đồng. Tuy nhiên nó phải sống, gần gũi mật thiết hằng ngày với người trồng lúa nước ở trên đồng cũng như con trâu đi trước cái cày theo sau trong nền văn hóa Đồng Sơn. Nó được xem như là mô típ trang trí được ghi khắc trên trống đồng làm cho ta liên tưởng đến con cò, con hạc hay con sếu. Các chim nầy đều có mỏ dài và chân cao cả nhưng xét dưới gốc độ gần gũi và thân thiết với người nông dân Việt thì cò ở đâu cũng có hiên diện không những trên ruộng đồng Viêt Nam mà luôn cả trong tục ngữ ca dao Việt Nam. Còn xét duới gốc độ tín ngưỡng thì hạc là loại chim có tính biểu tượng cao thượng được thấy ở các nơi thờ tự như ở Văn Miếu (Hànội). Nhìn lại lịch sử và truyền thuyết thì người Việt cổ (hay Lạc Việt) đã thừa nhận họ là thị tộc Hồng Bàng (tức là chim và rắn tức là Tiên Rồng). Như vậy họ đã ghép cho vật tổ của họ là Chim và Rắn rồi với quan niệm song trùng lưỡng hợp (hai trong một) theo học giả Hà Văn Thùy. Bởi vậy họ tự cho họ là con Rồng cháu Tiên. Tên Văn Lang có nguồn gốc từ tiếng Việt cổ là Blang hay Klang mà các dân tộc miền núi thường dùng để ám chỉ vật tổ, có thể đây là một loài chim nước thuộc họ chim Diệc. Có thể xem thời đó nước Văn Lang như một liên bang của các cộng đồng tộc Việt. Đây cũng là nhà nước đầu tiên của tộc Việt theo truyền thuyết trong lịch sử Việt Nam. Nói như nhà văn Đinh Hồng Hải thì cần có những phương pháp nghiên cứu sâu hơn để làm rõ danh tính của loại chim nầy. Còn sử gia Trần Gia Phụng, những hình ảnh trên trống đồng đều là hình “câm”. Bởi vậy giả thuyết nầy chỉ là sự phỏng đoán chưa có phần kết luận. Giả thuyết nào hợp lý sẽ đứng vững mà thôi.

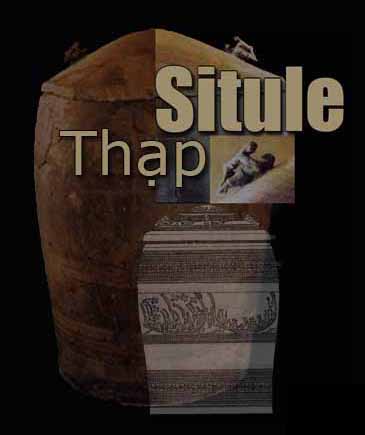

Cette question est souvent posée après la découverte d’ un grand nombre d’objets datant de l’âge de Bronze dans la vallée de Mã, notamment dans le village de Ðồng Sơn en 1924 par les archéologues de l’Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient (BEFO) (Louis Pajot, Olov Jansen). Puis, sur la proposition de l’archéologue autrichien R. Heine-Geldern, cette culture a été appelée « culture de Đồng Sơn », c’est-à-dire la culture des Proto- Vietnamiens. (ou des Luo Yue)

En outre, à cause du différend de longue date sur l’origine du tambour de bronze entre le Vietnam et la Chine, il y a aussi un débat sur les images décoratives trouvées sur la surface du tambour, en particulier un oiseau de quelle famille il s’agit. On n’arrive pas à l’identifier avec ses longues pattes et son long bec en posture volante ou assise. L’érudit Đào Duy Anh l’a reconnu par erreur dans son livre intitulé « Histoire ancienne du Vietnam » en affirmant que cet oiseau Lạc (Luo) semblable à une oie sauvage était l’oiseau totémique des Lo Yue (ou des Proto-Vietnamiens)? Autrefois, les clans de la société primitive avaient l’habitude de prendre souvent le nom du clan pour l’attribuer à leur totem. C’était le cas de l’oiseau Lạc (ou Luo). Selon l’historien Trần Gia Phụng ou l’écrivain Đinh Hồng Hải, malgré sa fausse théorie, l’érudit Đào Duy Anh continua à convaincre l’opinion publique car il fut l’un des érudits de renom au Vietnam à cette époque. Personne n’osa contester sa capacité de discernement mais par contre cela créa en revanche une idée de relation très étroite entre les Luo Yue et cet oiseau. Puis cette idée devint ainsi un jour sans même en rendre compte l’acceptation du nom « Luo » (ou Lạc) en vietnamien pour cet échassier, l’oiseau totémique des Luo Yue. Selon l’historien Trần Gia Phụng, tous les livres historiques contenant le mot « Lạc » ou (Luo) » comme « Thủy kinh chú » de Lịch Đạo Nguyên ( 6ème siècle) ou « Les archives abrégées d’An Nam » de Lê Tắc (13ème siècle) sont basées essentiellement sur le livre ancien chinois « Giao Châu ngoại vực ký » dont la date d’édition a lieu à l’époque des Jin (265-420) et dans lequel figure un paragraphe écrit en caractères Han-Viet comme suit: Giao Chỉ tích hữu quận huyện chi thời, thổ địa hữu lạc điền. Kỳ điền tòng thủy triều thượng hạ. Dân khẩn thực kỳ điền, nhân các vị Lạc dân, thiết Lạc vương, Lạc hầu chủ chư quận huyện.

Autrefois, lorsque Jiaozhi (ou Viet Nam) n’était pas encore un district, sa terre possédait des champs des riz appelés des champs « Luo ». En fonction de la montée ou la descente des marées, ces derniers étaient labourés. Les gens qui y travaillaient étaient appelés les Luo Yue (Les gens de Luo). Leur roi était connu sous le nom «Roi Luo (Lạc Vương », leurs marquis « Luo » étaient appelés « Lạc hầu » et ils avaient la mission de contrôler les districts. Il y a beaucoup de généraux ayant des sceaux en bronze avec la soie bleue.

Le mot « Lạc » ci-dessus est prononcé en caractère sino-vietnamien (Hán Việt) par les Vietnamiens. Par contre les Chinois le prononcent en recourant à la transcription phonétique. Ce mot phonétique devient ainsi « lo, ló, lô ». C’est le cas du nom de la capitale Lạc Dương des Chu qui devient Loyang lors de la transcription phonétique en chinois. Que devient-il le mot « lo, ló, lô » employé par le Chinois dans la langue des Proto-Vietnamiens ? Il désigne le paddy ou le riz. C’est pourquoi de la région Thừa Thiên jusqu’à la province Nghệ An du Viet Nam, tout le monde est habitué à employer le mot « ló » pour faire allusion au riz. Dans la région Quảng Bình du Centre-Vietnam, il y a un proverbe suivant « Cơm mô cho vừa bụng chó, ló mô cho vừa bụng gà»(Le riz cuit donne satisfaction au ventre du chien tandis que le grain de riz remplit bien l’estomac du poulet). Étant en caractère sino-vietnamien, le mot « Lạc » n’a aucune signification car il s’agit bien d’une transcription phonétique employée par les Chinois à partir du mot ló des Proto-Vietnamiens (ou des gens de Jiaozhi) pour les désigner comme des gens ayant la culture du riz inondé. C’est pourquoi quel que soit le radical employé avec le mot « Lạc », les Chinois continuent à le prononcer en Ló selon la remarque du feu érudit Hoàng Văn Chí dans son livre intitulé «Duy văn sử quan ». Aujourd’hui, il reste pas mal des montagnards ou des gens locaux de notre Vietnam continuent à employer le mot « ló» pour évoquer le riz comme les gens de Hà Tĩnh, Nghệ An, Quảng Bình ou le mot «lọ» dans la région de Thanh Hóa. Selon l’écrivain Đinh Hồng Hải, les cousins proches des Vietnamiens, les Mường le prononcent avec un accent situé entre les mots lỏ et lo (cơm mường vó, lọ mường vang) pour évoquer le riz de la région Mường Vó et le paddy de Mường Vang. Ainsi on peut dire que l’oiseau Lạc n’existe pas réellement dans la nature de notre pays. On ne trouve pas non plus son nom dans les dictionnaires vietnamiens. Il n’est en aucun cas l’oiseau totémique des Proto-Vietnamiens sinon on doit le trouver au centre de la surface du tambour de bronze.

La grue au temple de la littérature

Cependant, il doit être proche des riziculteurs et vivre quotidiennement avec eux dans le champ comme le buffle précédant la charrue dans la culture de Đồng Sơn. Il est considéré comme un motif de décoration gravé sur le tambour en bronze. Cela nous fait penser à une aigrette ou une grue. Ces oiseaux ont tous de longs becs et de hautes pattes, mais compte tenu de la proximité et de l’intimité journalière avec les riziculteurs vietnamiens, les aigrettes sont présentes partout non seulement dans les champs mais aussi dans les chansons populaires. Du point de vue religieux, la grue est une sorte d’oiseau afférent au caractère noble que l’on retrouve dans les lieux de culte comme au Temple de la Littérature (Văn Miếu, Hanoï). En jetant un regard dans l’histoire et les légendes des Lo Yue (Lạc Việt) ou Proto- Vietnamiens (ou Lac Viet), ils se reconnurent depuis la nuit des temps comme des gens appartenant au clan Hồng Bàng (Hồng désignant l’oiseau et Bàng le serpent càd l’Immortelle et le dragon). C’était pourquoi ils avaient associé à leur totem le couple (Oiseau/Dragon) avec la notion de dualité (deux en un) selon l’érudit Hà Văn Thùy. Ils étaient fiers d’être Enfants du Dragon et Grands Enfants de l’Immortelle (Con Rồng cháu Tiên). Le nom Văn Lang est dérivé de l’ancien mot Yue Blang ou Klang que les montagnards utilisent souvent pour désigner le totem, c’est peut-être un oiseau aquatique de la famille des hérons. Le royaume de Văn Lang peut être considéré à cette époque comme une fédération de communautés ethniques Yue. C’est aussi le premier état de l’ethnie Yue selon la légende de l’histoire vietnamienne. Selon l’écrivain Đinh Hồng Hải, il faut des méthodes de recherche approfondies pour clarifier l’identification de cet échassier. Pour l’historien Trần Gia Phung, les images trouvées sur les tambours sont toutes « muettes ». Par conséquent, cette hypothèse n’est qu’une conjecture sans conclusion. Toute hypothèse logique sera debout seulement.

Références bibliographiques

- Đinh Hồng Hải. Những biểu tượng đặc trưng trong văn hóa truyền thống Việt Nam. Tập 3. Các con vật linh. Nhà xuất bản Thế Giới.

- Trần Gia Phụng: Hình chim trên trống đồng Lạc Việt.

- Hoàng văn Chí. Duy văn sử quan. Nhà Xuất bản Cành Nam, Hoa Kỳ,1990 tt 78-79

- Đào Duy Anh: Lịch sử Việt Nam. Nhà Xuất Bản Văn hóa thông Tin 2002