French version

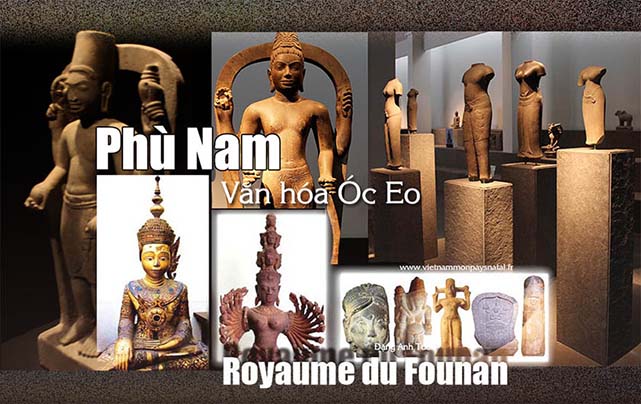

Funan kingdom

Until the dawn of the 20th century, the information was received about this old Hinduized kingdom in some Chinese texts. It was mentioned during the Three Warring States period of Chinese history (Tam Quốc )(220-265) in Chinese writings since the establisment of diplomatic relations between the Wu state (Đông Ngô) and foreign countries. In this report, it is noted that the governor of Guandong and Tonkin provinces, Lu-Tai sent representatives (congshi) in the south of his kingdom. The kings, beyond the borders of his kingdom (Funan, LinYi (future Chămpa) and Tang Ming (country identified in the northern Tchenla at the time of Tang dynasty) sent each other an ambassador to pay him their tribute. Then Funan was also quoted in the dynastic annals from the Tsin dynasty (nhà Tấn) until the Tang dynasty (Nhà Ðường).

Even the name of Funan is the phonetic transcription of the old khmer word bhnam (mountain) in Chinese characters. It still gives rise to reservations and reluctances in the interpretation of Funan by « mountain » for some experts. These one find the justification of the name « Funan » in the best sense of « hillock » because, until quite recently, in the ethnographical studies [Martin 1991; Porée-Maspero 1962-69] , the Khmer were used to practising ceremonies around the artificial hillocks. Being affected by this custom that they did not know, the Chinese have made reference to this mode of practice for designating this kingdom. Thanks to archaeological excavations which took place in 1944 at Óc Eo with French Louis Malleret in An Giang province located into the south of present-day Vietnam, the existence and prosperity of this Indianised kingdom have not been in doubt. The results of these excavations had been written in his doctoral thesis, then published in an entitled work « Archaeology of the Mekong delta » representing 6 volumes.

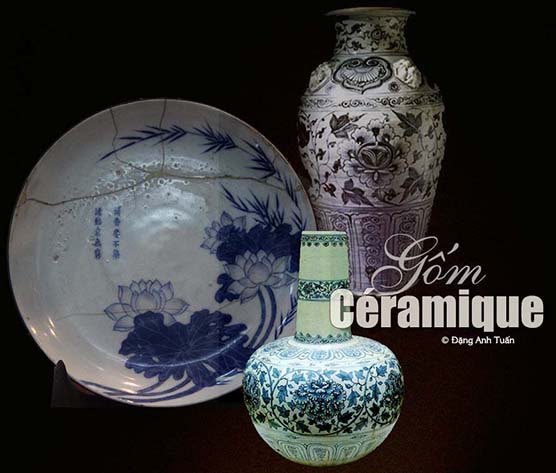

© Đặng Anh Tuấn

This allows to confirm the Chinese informations and to make them a little more precise in the confinement and localization of this kingdom. Because of the abundance of tin archaeological finds, French archaeologist Louis Malleret did not hesitate to borrow the name Óc Eo for designating this tin civilization. We begin to have now a deep light on this kingdom as well as its external relations during the resumption of excavations undertaken both by Vietnamese teams (Đào Linh Côn, Võ Sĩ Khải, Lê Xuân Diêm) and French-Vietnamese team led by Pierre-Yves Manguin between 1998 and 2002 in An Giang, Ðồng Tháp and Long An provinces where a large number of sites of Óc Eo culture are located.

We know that Óc Eo was a major port of this kingdom and was a transit hub in trade exhanges between the Malaysian peninsula and India on one hand and between the Mekong and China on other one. As the boats of the region could not cover long distances and had to follow the coast, Óc Eo thus became a mandatory stop and a important strategic step during the 7 centuries of blooming and prosperity for Funan kingdom.

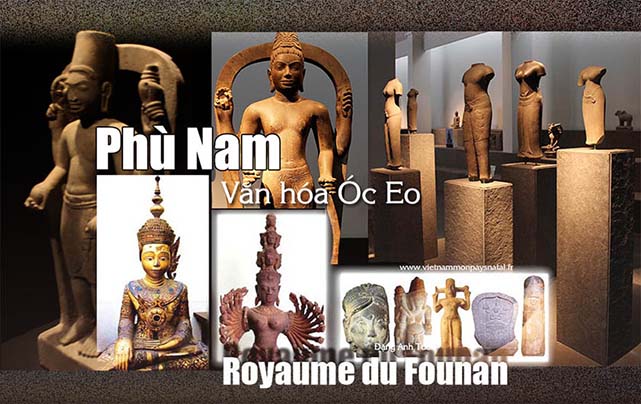

Óc Eo civilization

Pictures gallery

This one occupied a quadrangle included between the gulf of Thailand and Transbassac (western plains of Mekong delta or miền tây in Vietnamese) in the South of Vietnam. It was bounded in the northwest by the Cambodian border and in the southeast by Trà Vinh and Sóc Trăng cities. Aerial photos taken by the French people in the 1920s revealed that Funan was a maritime empire (or a thalassocracy).

The Chinese authors tell us that immense city states, encircled by successive lines of earthen ramparts and ditches formely filled by crocodiles, were divided into districts by the ramification of canals and arteries. We can imagine houses and stores on piles, bordered by ships as in Venice or in the Hanseatic cities. We discover in this surprising network constituted by stars of rectilinear canals arranged according to the northeast / southwest frame (from Bassac towards the sea) and all communicating with each other, its important role for evacuating Bassac floodwaters towards the sea. This allows to wash the soil with alum, repulse headways of brackish water during Bassac floods, favor the floating rice, ensure especially the provisioning inside the kingdom by cargoes of coastal navigation coming from China, Malaysia, India and even from Mediterranean circumference.

The discovery of gold coins bearing Antonin le Pieux (in 152 A.D.) or Marc Aurèle’s effigies and low-reliefs carvings of Persian kings testifies to the important role of this kingdom in trade exchanges at the beginning of the Christian era. There is even a grand canal allowing to connect the port city Óc Eo on one hand with the sea and on the other hand with the Mekong and the ancient city of Angkor Borei, located 90 km upstream in the Cambodian territory. This one would be presumably the capital of Funan in its decline.

For French archaeologist Georges Coedès, there is no question that the Angkor Borei site corresponds exactly to that of Na-fou-na, described in Chinese texts as the city where kings of Funan wildrew after their eviction from the ancient capital of Funan, Tö-mu, identified as the city Vyàdhapura located in the Bà Phnom region of the Cambodian territory by Georges Coedès [BEFEO, XXVIII, p. 127]. The wealth of this archeological site and the variety of archeological remains originating from it, confirm his affirmation.

Thanks to archeological finds that have been recovered during all series of excavations on the complex of Óc Eo sites, we can say that this kingdom knew three important periods during its existence:

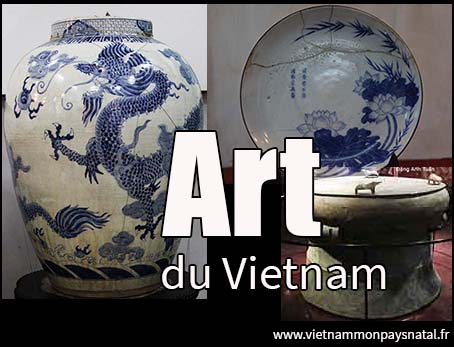

The first period which extends from the 1st to about 3th century, distinguishes itself by terra-cottas (ceramic potteries, bricks, tiles), glassware (pearls and necklaces), silverware (rings, earrings), stones sculptures (seals, signet rings, cabochons), copper, iron, bronze and especially tin objects.

We attend the first human activity on hillocks in the Óc Eo plain and on low slopes of Ba Thê mountain. The habitat is on piles and wood. The common jar grave in the South-East Asia is still practised. The process of the Indianisation is not yet started by the absence of statuaries and religious relics. But there is, all the same, a regular contact between this kingdom and India.

The commercial exchange is strengthened by local alliances and Indian teachers arrival. These one, retained longer for their stays in this kingdom because of the season of monsoons, continued to practise their religions (Brahmanism, Buddhism). They began to make emulators among the natives and to help the latter in the implementation of a hydraulic network allowing to drain the flooded plain, until now, hostile and to make it « useful » for the habitat, cultivation and development of their kingdom. The Indians were known to realize advisedly the works of agricultural hydraulics and cultivation. It is what we have seen in the country of the Tamils during the Pallava period for example.

The floating rice cultivation is attested by the traces of use of this graminaceous plant as degreasing agent for pottery. For French researcher of CNRS, J.N. Népote, specialist of the Indo-Chinese peninsula, Funan kingdom received most of its revenues from the agricultural sector in the technique of floating rice.

It was not necessary to cultivate the soil nor to sow and even less to plant rice seedlings in this time when the coastal fringe of Funan was an flooded zone of polders. The rice grew alone at the same time as the water level, this one being able to reach three metres in height. The rice was later harvested by boats. For the floating rice, the only constraint to be required was the distribution and regulation of floods by the digging of canals in order to be better able to manage the irrigation water and facilitate the means of communication.

The second period of the Funan history (4th- 7th centuries) is marked by the discovery of a large number of Vishnouist and Buddhist religious monuments on the hillocks of Oc Eo plain and on the slopes of Mount Ba Thê. The emblematic figures of the Indian pantheon (Shiva, Vishnu, Brahma, Nanin, Ganesha and Buddha) were exposed. It is also the period when the piled wooden housing moves from hillocks towards flooded plain and low slopes of Ba Thê mountain.

The indianisation of the kingdom was underway when we saw around 357 an Indian of Chinese name Tchou Tchan-t’an, being perhaps of Scythian origin and Kanishka descent, to reign in Funan kingdom [Founan: Paul Pelliot, p 269], which could explain the success of the Surya cult and its iconography in the Funan art. Another Brahman of Chinese name (Kiao-Tchen-Jou) (or Kaundinga-Jayavarma) will succeed him and will reign in Funan kingdom between 478 and 514. It is the period quite known thanks to local inscriptions in sanskrit.

Even the myth of the kingdom’s foundation comes from India: a Brahman named Kaundinya, guided by a dream, get a magic bow in a temple and navigates towards these banks where he manages to beat the girl named Soma of the native sovereign presented as Naga king (a fabulous snake) then he marries her to govern this country. We can say that during this period, the Funan kingdom knew its peak and maintained close relations with China.

The magnitude of its trade was indisputable by the discovery of a large number of objects other than that of India found on Funan banks: fragments of bronze mirrors dating from the Han anterior period, Buddhist bronze statuettes attributed to Wei dynasty, a group of purely Roman objects, statuettes of Hellenistic style in particular a bronze representation of Poseidon. These objects were probably exchanged for goods because Funan people only knew the barter. For the purchase of valuable products, they used golden and silver ingots, pearls and perfumes. They were known as excellent jewelers. The gold was finely worked with numerous Brahmanic symbols. Jewels (golden earrings with the delicate clasp, admirable golden filigrees, glass pearls, intaglios etc.) exposed in the museums of Đồng Tháp, Long An and An Giang testifies not only of their know-how and their talent but also the admiration of the Chinese in their narratives during their contact with Funan people.

The last period corresponds to the decline and end of Funan kingdom. A important change was indicated during period tcheng-kouan (627-649) to Funan kingdom in the Chinese annals. The kingdom of Tchen-la (Chân Lập) (future Cambodia) situated in the southwest of Lin Yi ( uture Champa) and country vassal of Funan took over the latter and subjugated it. This fact was not only reported in the new history of Tang (618-907) of Chinese historian Ouyang Xiu but also on a new inscription of Sambor-Prei Kuk in which king of Tchen La, Içanavarman was congratulated for having increased the territory of his parents. One thus bear witness to the abandonment of habitat and religious sites in the plain Óc Eo because the centre of gravity of the new political formation coming from the North leaves the coast to gradually approach the site of the future capital of Khmer empire, Angkor.

For French researcher J. Népote, the Khmers come from the North by Laos appear as Germanic bands against the Roman empire, try to establish inside lands a unitarian kingdom under the name of Chen La. They have no interest to keep the technique of the floating rice because they live far from the coast. They try to combine their own mastery of water storage with the contributions of Indian hydraulic science (barays) to finalize through multiple experimentations an irrigation better adjusted to the hinterland ecology and local varieties of irrigated rice.

In spite of the recent discoveries confirming the existence of this kingdom, many questions have remained unanswered. We do not know who were the indigenous people populating this kingdom. One thing is for sure: they were not Vietnamese who had arrived only in the Mekong delta in the 17th century. Were they ancestors of the Khmers? Some had this conviction when Louis Malleret began excavations in the 1940s because the toponymy of the region was totally Khmer. At the time of Funan, it was yet not clear what this is. However, thanks to the study of osseous remains of Cent-Rues (in the peninsula of Cà Mau), we are dealing with a population very close to Indonesians (or Austro-Asiatic ) (Nam Á).

A Mon-Khmer contribution in the North of this kingdom can be possible to give to Funan the juxtaposition and the fusion of two strata which are not far away from each other before becoming the race of Funan people. In this hypothesis frequently accepted, the Funan people were the proto-Khmers or the cousins of the Khmers. The absorption of a city of Malaysian peninsula (known under the name Dunsun in the Chinese sources reporting this fact ) in the 3th century by Funan in an area where the Mon-Khmer influence is undeniable, is one of the determining elements in favour of this hypothesis.

In what conditions did Óc Eo disappear? Nevertheless Óc Eo played an economic role in commercial exchanges during seven first ones centuries of the Christian era. The archaeologists continue to look for the causes of the disappearance of this port city: flood, fire, deluge, epidemic etc. …

Is the Funan kingdom a state unified with a strong central power or is it a federation of centers of urbanized and sufficiently autonomous political power on the Indo-Chinese peninsula as on the Malaysian peninsula so that we qualify them as city-states?

P.Y.Manguin has already raised this question during a colloquium organized by Copenhagen Polis centers on the city-states of the coastal South-East Asia in December, 1998. Where is its capital if the central power is strongly emphasized many times by the Chinese in their texts? Angkor Borei, Bà Phnom are they really the former capitals of this kingdom like that has been identified by French Georges Coèdes? For the moment, what has been found does not bring answers but it only redoubles the envy and desire of archaeologists to find them in the coming years because they know that they have the feeling of dealing with brilliant civilization of the Mekong delta.

Bibliography references

Georges Coedès: Quelques précisions sur la fin du Founan, BEFEO Tome 43, 1943, pp1-8

Bernard Philippe Groslier: Indochine, Editions Albin Michel, Paris

Lê Xuân Diêm, Ðào Linh Côn,Võ Sĩ Khai: Văn Hoá Oc eo , những khám phá mới (La culture de Óc Eo: Quelques découvertes récentes) , Hànôi: Viện Khoa Học Xã Hội, Hô Chí Minh Ville,1995

Manguin,P.Y: Les Cités-Etats de l’Asie du Sud-Est Côtière. De l’ancienneté et la permanence des formes urbaines.

Nepote J., Guillaume X.: Vietnam, Guides Olizane

Pierre Rossion: le delta du Mékong, berceau de l’art khmer, Archeologia, 2005, no422, pp. 56-65.