Nghê thuật Chămpa

Nghê thuật Chămpa

Version vietnamienne

English version

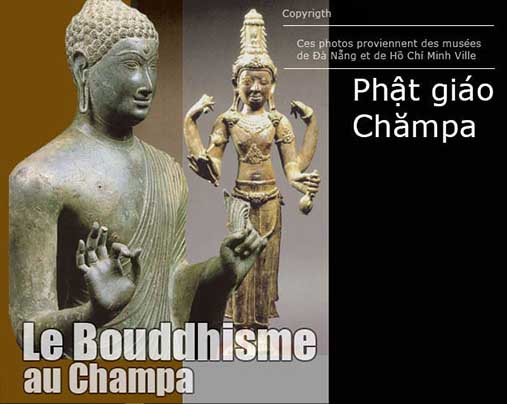

L’art cham continue à représenter une partie importante dans l’art du Sud Est Asiatique connu dans le passé sous le nom « art trans-indien ». On le trouve par le biais de leurs vestiges architecturaux religieux. Ceux-ci deviennent la clé de voûte de l’art Cham. Bien que ces édifices ne soient pas des monuments splendides et grandioses comme Pagan en Birmanie, Angkor au Cambodge, Borobudur en Indonésie, ils sont d’une grande beauté pleine de charme. Certains méritent de faire partie des patrimoines mondiaux de l’humanité car on y trouve à la fois une décoration composée de riches sculptures en grès et des motifs ornementaux finement gravés dans les briques. On peut dire que c’est une broderie de briques et de grès, un joyau unique en son genre pour l’humanité. Rien n’est étonnant de voir la cité sainte Mỹ Sơn d’être classée comme l’un des patrimoines mondiaux de l’humanité.

Les habitants de l’ancien Champa ont incarné leur âme dans la terre et dans la pierre et ont su tirer parti de la nature pour en faire un Mỹ Sơn splendide, mystérieux et grandiose. C’est un vrai musée architectural, sculptural et artistique du monde de valeur inestimable qu’il est difficile de comprendre entièrement.

Feu architecte Kasimierz Kwakowski

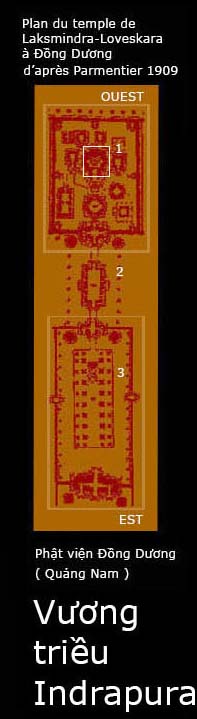

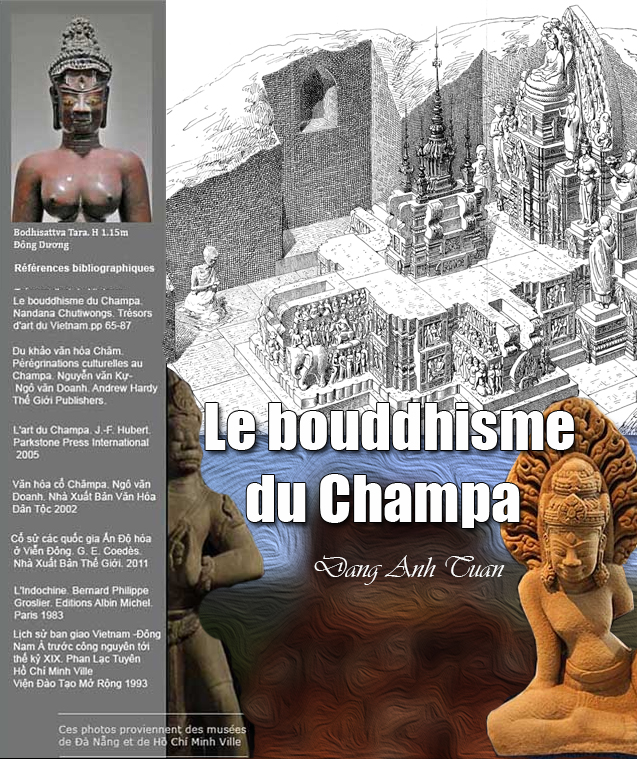

L’architecture chame est d’inspiration indienne. Les ouvrages architecturaux sont des ensembles comprenant un temple principal (ou kalan en langue chame) entouré de tours et de temples, le tout englobé dans une enceinte.

Les temples sont bâtis en forme de tour et en briques tandis que les linteaux, les bas-reliefs, les corniches, les tympans etc .. sont en grès. Les règles de la disposition des temples cham ont été bien définies. Cela doit refléter la cosmogonie hindoue. Après avoir érigé le temple-tour, les sculpteurs Chams commencent à exécuter des bas-reliefs sur les murs du temple. Pour les ornements de décoration, ils se servent des motifs de fleurs, de feuilles, de branches, d’animaux et de scènes inspirées de l’histoire pour évoquer des sujets religieux.

Les temples et les tours chams sont construits avec des briques en terre cuite. Celles-ci sont associées à des ornements en grès: jambages, pilastres, linteaux etc … De dimensions variées, ces briques dont les formes sont souvent parallélépipédiques sont chauffées à petit feu. Malgré l’absence du mortier, elles continuent à rester soudées les unes des autres au fil des siècles, ce qui permet aux tours et aux temples de résister tant bien que mal aux attaques des intempéries. Cela constitue encore une énigme pour la plupart des scientifiques et cela prouve que la technique de fabrication et d’utilisation des briques a atteint chez les Chams un très haut niveau.

Par contre, selon le chercheur vietnamien, spécialiste de l’art Cham, Trần Kỳ Phương, l’extraordinaire solidité de ces énormes blocs de briques agrégés entre eux provient de l’utilisation d’un mélange d’huile (dầu rái) venant de la résine de Pipterocarpus Alatus Roxb et de la chaux provenant de la cuisson des coquillages et de la poudre de brique. D’autres chercheurs n’hésitent pas à reprendre la vieille idée qui est pourtant abandonnée depuis longtemps. C’est celle d’une cuisson de l’édifice tout entier en une seule fois. C’est l’hypothèse émise par un chercheur vietnamien Ngô Văn Doanh dans son ouvrage intitulé « La culture du Champa, Editions Culture et Informations, Hanoï , 1994 » (Văn Hóa Chămpa, Thông Tin , Hanoï ).

En admirant ces tours, le voyageur ne peut pas retenir sa tristesse de voir disparaître l’une des civilisations brillantes d’Indochine dans les tourbillons de l’histoire. C’est à nous, les Vietnamiens de redonner à ce peuple vaincu la place et la dignité qu’il mérite dans notre société et de lui montrer notre attachement à sa culture. C’est seulement dans cet esprit d’ouverture et de tolérance que le Vietnam est fier d’être une mosaïque de 54 ethnies. C’est un apport culturel inouï à notre richesse culturelle millénaire.

Version vietnamienne

Nghệ thuật Chămpa vẫn tiếp tục là một bộ phận quan trọng của nghệ thuật Đông Nam Á được gọi là « nghệ thuật xuyên qua Ấn Độ ». Nó được tìm thấy thông qua các di tích kiến trúc tôn giáo. Các dấu tích kiến trúc nầy trở thành nền tảng của nghệ thuật Chămpa. Tuy không phải là những công trình kiến trúc lộng lẫy và hoành tráng như Pagan ở Miến Điện, Angkor ở Cao Miên, Borobudur ở Nam Dương, nhưng cũng mang lại vẻ đẹp tuyệt vời đầy quyến rũ. Một số di tích xứng đáng là một phần di sản thế giới của nhân loại bởi vì được tìm thấy ở trang trí các tác phẩm điêu khắc phong phú trên đá sa thạch và các họa tiết được chạm một cách tinh xảo trên gạch. Có thể nói, đây là bức tranh thêu bằng gạch và đá sa thạch, một loại ngọc có một không hai đối với nhân loại. Không có gì ngạc nhiên khi thánh địa Mỹ Sơn được xếp vào một trong những di sản thế giới của nhân loại.

Người Chàm cổ đã gởi tâm linh vào đất, đá và đã biết dựa vào thiên nhiên để làm nên một Mỹ Sơn tráng lệ, thâm nghiêm và hùng vĩ. Đây là một bảo tàng kiến trúc điêu khắc nghệ thuật vô giá của nhân lọai mà còn lâu chúng ta mới hiểu biết đựơc hết.

Cố kiến trúc sư Kasimierz Kwakowski

Kiến trúc Chămpa lấy nguồn cảm hứng từ Ấn Độ. Các công trình kiến trúc là những tổng thể gồm có một ngôi đền chính (hoặc kalan trong tiếng chàm) được các tháp và đền bao xung quanh, tất cả được bao bọc thêm ở ngoài bởi một vòng vây.

Các ngôi đền được xây dựng theo hình tháp và bằng gạch, còn các lanh tô, các phù điêu, các gờ kiến trúc, các ô trán vân vân… được làm bằng đá sa thạch. Các quy tắc bố cục của các đền tháp Chăm đã được xác định rõ. Nó phải phản ánh vũ trụ quan của người Hindu. Sau khi dựng xong đền-tháp, các nhà điêu khắc người Chăm mới bắt đầu làm những bức phù điêu trên tường của ngôi đền. Họ sử dụng các họa tiết trang trí như lá cây, hoa lá, động vật, thần linh vân vân … để gợi lên những chủ đề tôn giáo.

Các đền tháp chàm được xây dựng bằng gạch đất nung và được kết hợp với các đồ trang trí bằng đá sa thạch: chồng trụ, cột trụ tường, lanh tô vân vân… Với nhiều kích cỡ khác nhau, những viên gạch này, có hình dạng thường là hình hộp, được nung ở nhiệt độ thấp. Mặc dù không có vữa, các viên gạch nầy vẫn tiếp tục gắn liền với nhau qua nhiều thế kỷ, cho phép các tháp và đền thờ nầy có thể chống chọi lại không ít thì nhiều với thời tiết khắc nghiệt. Điều này vẫn còn là một bí ẩn đối với tất cả nhà khoa học và nó chứng tỏ rằng kỹ thuật chế tạo và sử dụng gạch đã đạt đến trình độ rất cao của người Chàm.

Mặt khác, theo nhà nghiên cứu Việt, một chuyên gia về mỹ thuật Chămpa, Trần Kỳ Phương, sự vững chắc lạ thường của những khối gạch khổng lồ nầy được kết hợp với nhau là do việc sử dụng hỗn hợp dầu từ nhựa cây dầu rái Pipterocarpus Alatus Roxb và vôi nấu từ các vỏ sò và bột gạch. Các nhà nghiên cứu khác không ngần ngại tiếp thu lại ý tưởng cũ đã bị bỏ rơi từ lâu. Đó là việc nung nguyên toà nhà cùng một lúc. Đây là giả thuyết được nhà nghiên cứu Việt Nam Ngô Văn Doanh đưa ra trong tác phẩm “La culture du Champa, Editions Culture et Informations, Hanoi, 1994” (Văn Hóa Chămpa, Thông Tin, Hà Nội).

Khi được chiêm ngưỡng những tháp này, người lữ khách không khỏi bùi ngùi khi chứng kiến sự diệt vong của một trong những nền văn minh rực rỡ ở Đông Dương trong cơn lốc lịch sử. Người dân Việt chúng ta cần phải trả lại cho một dân tộc bị bại trận nầy vị trí và phẩm giá mà họ rất xứng đáng có được ở trong xã hội của chúng ta và cho họ thấy chúng ta rất gắn bó mật thiết đối với nền văn hóa của họ. Chỉ với tinh thần cởi mở và khoan dung mà Việt Nam mới có thể tự hào là bức tranh khảm của 54 dân tộc. Đây cũng là sự đóng góp văn hóa phi thường của họ vào nền văn hóa mà chúng ta có hơn nghìn năm tuổi.

English version

Cham art continues to be an important part of Southeast Asian art known in the past as « trans-Indian art ». It is found through their religious architectural remains. These become the keystone of Cham art. Although these buildings are not splendid and grandiose monuments like Pagan in Burma, Angkor in Cambodia, Borobudur in Indonesia, they are of great beauty and charm. Some of them deserve to be part of the world heritage of humanity because they are decorated with rich sandstone sculptures and ornamental patterns finely engraved in the bricks. It can be said that it is an embroidery of bricks and sandstone, a unique jewel for humanity. No wonder the holy city Mỹ Sơn to be listed as one of the world heritage sites of mankind.

The people of ancient Champa have embodied their soul in the earth and stone and have taken advantage of nature to make a splendid, mysterious and grand Mỹ Sơn. It is a true architectural, sculptural and artistic museum of the world of priceless value that is difficult to fully understand.

The late architect Kasimierz Kwakowski

Chame architecture is inspired by Indian architecture. The architectural works are complexes consisting of a main temple (or kalan in the Chame language) surrounded by towers and temples, all enclosed in a compound.

The temples are built in the form of a tower and in brick while the lintels, bas-reliefs, cornices, tympanums etc. are in sandstone. The rules for the layout of Cham temples have been well defined. It must reflect the Hindu cosmogony. After erecting the temple-tower, Cham sculptors start to execute bas-reliefs on the temple walls. For the decorative ornaments, they use motifs of flowers, leaves, branches, animals and scenes inspired by history to evoke religious subjects.

Cham temples and towers are built with clay bricks. These bricks are associated with sandstone ornaments: jambs, pilasters, lintels etc… Being of various dimensions, these bricks whose forms are often parallelepipedic are heated over a small fire. Despite the absence of mortar, they continue to be welded together over the centuries, which allows the towers and temples to resist the attacks of the weather. This is still an enigma for most scientists and it proves that the technique of making and using bricks has reached a very high level among the Cham.

On the other hand, according to the Vietnamese researcher, specialist in Cham art, Trần Kỳ Phương, the extraordinary solidity of these huge blocks of bricks aggregated together comes from the use of a mixture of oil (dầu rái) coming from the resin of Pipterocarpus Alatus Roxb and lime coming from the cooking of shells and brick powder. Other researchers do not hesitate to take up the old idea that has long been abandoned. It is that of a cooking of the whole building at once. This is the hypothesis put forward by a Vietnamese researcher Ngô Văn Doanh in his book entitled « La culture du Champa, Editions Culture et Informations, Hanoi , 1994 » (Văn Hóa Chămpa, Thông Tin , Hanoi ).

While admiring these towers, the traveler cannot hold back his sadness to see one of the brilliant civilizations of Indochina disappearing in the whirlwinds of history. It is up to us, the Vietnamese, to give back to this defeated people the place and dignity they deserve in our society and to show our attachment to their culture. It is only in this spirit of openness and tolerance that Vietnam is proud to be a mosaic of 54 ethnicities. It is an incredible cultural contribution to our millennial cultural wealth.