Part 1 (Yin and Yang theory)

Part 2 (Yin and Yang theory)

Part 3 (Yin and Yang numbers)

The Yin and Yang theory continues to manage the daily life of the Vietnamese, down to the last detail. The Yin nature is everything being fluid, cold, humid, passive, dark, interior, immobile and originating from feminine essence as the sky, moon, night, water and winter. But everything being solid, hot, light, active, exterior, mobile and coming from the male essence as soil, sky, fire and summer belongs to the Yang nature. This bipolarity is even found in the Vietnamese grammar by using the words « con » and « cái ». Similar to French articles defined « le » and « la », these are employed to indicate the type in certain cases but one can rely on the nature « mobile » or « immobile » of the object accompanied for indicating its belonging in the corresponding semantic class. The word cái is used in case where the object carries the character « immobile » (tĩnh vật) : cái nhà (house), cái hang (cave), cái nồi ( pot) etc… However, when the state « mobile » (động vật) belongs to the object nature, the word « con » is used instead of « cái ». It is the case of the following words: con mắt (eye), con tim ( heart), con trăng ( viper), con ngươi ( pupil), con dao ( knife) etc… The eye moves incessantly as the throbbing heart. Similarly, the viper moves as well as the pupil. The knife is considered by the Vietnamese as a sacred animal. It is nourrished with blood, wine and rice. The same name beared by an object can lead to two different interpretations depending on the use of the word « cái » or « con« . The following example reflects the character « mobile » or « immobile » of the object « thuyền » ( or boat ) employed : Con thuyền trôi theo dòng nước (The boat moves on the water). This mean someone drives forward the boat with oar or engine. However, when one says « cái thuyền trôi theo dòng nước » (The boat moves on the water), one insists on the fact that nobody does not manoeuvre the boat. It is the flood waters that drives forward the boat alone. This notes the character « immobile » of the boat. The influence of Yin and Yang is no stranger to the way of attributing the sex to common objects. It is the case of the knife (dao): dao cái (large knife), dao đực ou dao rựa (or machete). This remark has been notified by French archeologist and sinologist Alain Thote in his article intituled « Origine et premiers développements de l’épée en Chine « : The Yue swords enjoyed the very high celebrity in ancien times. Some swords had the name and one was brought to consider their belonging to the male or female sex. The expression « đực rựa » used frequently in conversations for designating the men, is from the custom of the old Vietnamese carrying machetes during the walk.

The gender association is also visible for a long time in Vietnam in rice cultivation: the man ploughs and the woman pricks out in the field. The plougshare penetrating the soil (Yin) symbolizes the male sex (Yang) while the woman transmits the power of fertilization (Yin) to rice plants (Yang) by transplantation. For showing the complete perfection in the harmonious union of Yin and Yang, one has the habit of saying in Vietnamese: Being together, husband and wife achieve to scoop all the water from the East sea. (thuận vợ thuận chồng tát biển Đông cũng cạn).

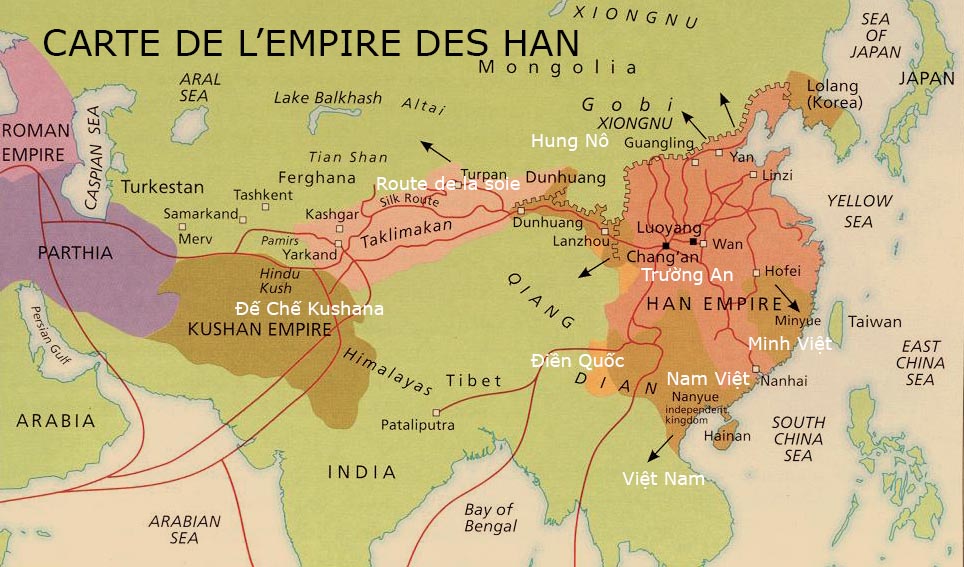

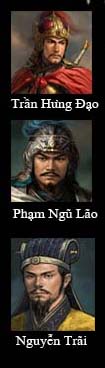

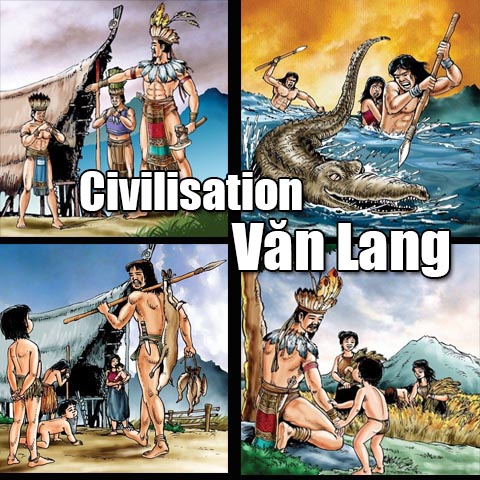

Being ric farmers, the Proto-Vietnamese were attached not only to the soil but also to the environment because thanks to the natural phenomena ( rain, sky, wind, cloud etc…) , they had successful harvests or not. The extensive agriculture in slash/burning or in flooded terrains depended on the vagaries of climate. That is why they needed to live in harmony with nature. They considered that they were the link between Heaven and Earth (Thiên-Nhân-Địa). From this notion, one has the habit of saying: Thiên Thời, Địa Lợi, Nhân Hòa (to be aware of weather,to know the environment and to have popular support or national harmony). There are three key factors of success to which Vietnamese strategists (Trần Hưng Đạo, Nguyễn Trãi or Quang Trung) referred, in their struggle against foreign invaders. The Vietnamese take into consideration this triad in their way of thinking and their daily life. For them, there is no doubt that this notion has an undeniable influence on man himself: his destinity is imposed by the will of Heaven and depend on his date of birth. With the exterior and interior environment of his home, he can receive the harmful or beneficial breath (qi) generated by the Earth. The art of harmonizing the exterior and interior environmental energy of his housing allows him to minimize his troubles and promotes his welfare and his health. A flat terrain without any undulations and no hills is the lifeless soil and shortness of breath qi (Khí). The Vietnamese call mountains and hills with the names Dragons and Tigers. Buildings should have respectively a green Dragon and a white tiger in the west and east facing. The caring dragon must be more powerful than the tiger (Hữu Thanh Long, Tã Bạch Hổ), that means the Dragon mountain is higher than the Tiger hill. The best site is that which has a hill behind one another, which enables to show the interlacing between the Dragon and the Tiger. The concept of harmony takes on its full meaning when a site backed by a mountain and surrounded on two sides by ranges of hills allowing its protection against winds for avoiding the dissipation of Chi (or cosmic energy), provides access to a lake or a river where there are both water and nourrishment and the accumulation of cosmic energies. This model is found by taking the example of historic city of Huế. The enclosure of this latter is a defensive military structure based on the technique of strengthened fortifications of renowned engineer, Vaubanand covers near the southern front, the imperial city delimited by a second square-enclosed area mesuring approximatively 622m x606 m. Therein, one finds the Forbidden Purple City forming the symbolic heart of the empire in the third and last enclosure, having nearly a square in shape and mesuring 330×324 m. The imbrication of three enclosures refers to the triad (Thiên, Nhân, Ðịa). Facing to the 105 m high mountain Royal Screen (or Ngự Bình in Vietnamese) that, according to the geomancers interpretation (Feng Shui)(Phong Thủy), is the imperial shield created by Gods, the citadel’s southern front including the moon gate (or Ngọ Môn), follows the convex alignment along the Perfume river (Hương giang). Being similar to the dragon lying in the West, this river undulates and goes up in the north by penetrating the soil through small hills and making a 45° bend towards the east. It reachs firstly protectives isles Dã Viên and Cồn Hến before ending in the sea. That creates the ideal position (Chi Huyền Thủy) corresponding to the above described scheme with a green Dragon in the West and a white Tiger in the East. These animals are respectively represented by the shell isles Dã Viên and Cồn Hến in the face of the natural screen symbolized by the mount of Royal Screen (Núi Ngự Bình).

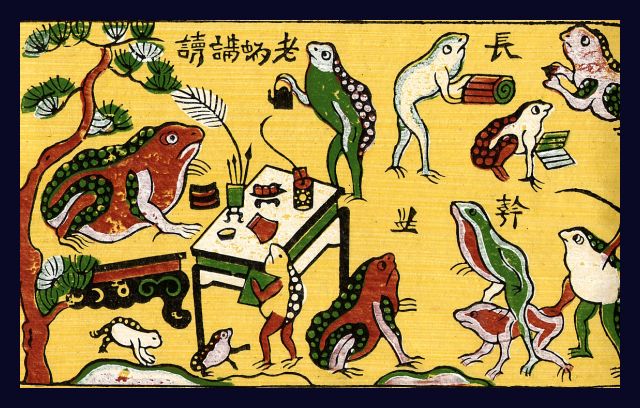

The man can affect his own life. By accomplishing acts of caring towards others, he can find his joy and improves his karma. In ancient times, Vietnam had a sacrificial ceremony named « Nam Giao » or « Tế Giao » intended to Heaven and Earth. It goes back to the king to pay homage to Heaven and Earth every year with his deified ancestors on the monumental esplanade built in 1806 in the southern suburb of Huế. One finds in this esplanade a square mound representating the Earth temple, in the center of which is an other round mound symbolyzing the Heaven temple. Being firstly subjected in complete isolation and fast, the king climbs the sacrificial esplanade and acts on behalf of his people for communicating with universe natural forces in order to ask them to improve the environment on earth. The king is the only figure eligible for being an intermediary between Earth and Heaven. This Triad (Thiên, Nhân, Địa) has also evoked in Vietnamese legends. One finds the narrator willingness to show the deep attachment of Vietnamese people to the triad notion in accordance with nature and moral. In the legend intituled « The God of Mountains and the God of Rivers (Sơn Tinh Thủy Tinh), a girl named Mị nương is requested in marriage by these two geniuses or in the Kitchen genius myth (Chuyện Táo quân), one finds a woman torn between the love of her old husband and that of her new companion. In the betel quid (Trầu Cau), the triad (wife, husband and brother) is represented by the woman, her husband and her twin brother-in-law who, once deceased, respectively become betel, arecanut palm and limestone. The betel quid reflects well the equilibrium notion and harmony found in the Yin and Yang theory. For preparing the betel quid, a little of slaked lime is smeared on a betel leaf. Then one adds some root bark of Artocarpus tonkinese in yellow-orange colour and finally incorporates a areca nut finely sliced. All this is introduced in the mouth and chewed slowly. After twenty minutes of chewing, one spits out what remains. Five tastes can be found in the betel quid: sweet with areca nut, spicy with betel leaf, sour with root bark, salty with lime and acidulous with saliva. By the image of fresh betel liana coming from Earth symbolized by lime stone and embracing the slender arecanut palm trunk in this legend, one wants to mention the intermediary character between the Yin and Yang in a perfect accord. The old Vietnamese adage says that the betel quid is the prelude to the conversation (Miếng trầu là đầu câu chuyện). The acceptation implies heavy consequences and is equivalent to a firm commitment, a word given that no one would ever think of taking back. If the exchange has taken place between girl and boy , this is equivalent to a proposal of marriage. In the Vietnamese tradition, the betel quid is the symbol of marital happiness. It cannot be missing in marriage riruels.

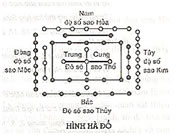

In the swamp rice civilization, others trinities are important as the triad (Heaven, Earth, Man). There is the case of the triad (Thủy, Hỏa, Thổ) (or (in English Water-Fire-Soil) or that of the triad (Mộc, Kim, Thổ)(or Wood, Metal, Soil). One needs soil for the rice cultivation, water and fertilizers coming from ashes caused by fire for enriching soils. Likewise, one needs plants for food and metals for making appropriate tools in agriculture. One oberves that these triads have a common element that is the soil. That is why this latter occupies a central position in the management of 4 cardinal points. There is the pivot around which fourth others elements take place. In the farm life, the most important element following the soil is water. One the habit of hearing from Vietnamese peasant the following saying: Nhất nước nhì phân (Firstly water, secondly fertilizers). Being of Yin nature, water is attributed to the northern direction because it is compatible with the cold (winter). On the contrary, being of Yang nature, fire found in the triad (Water-Fire-Soil) is better associated in the southern direction with the warmth and radiation (summer). The element « Wood » evokes plants, the birthday of which takes place in spring. It derserves to occupy the eastern direction with the development of Yang. Being element of malleable character and taking different forms, Metal is associated to the western direction (autumn).

The Vietnamese are founding in the Yin and Yang theory a practice of alternation rather than a idea of opposition. Yin and its complementary Yang form an identity that allows to result in the installation of right balance and harmony. For them, the word represents the totality of cyclical sequences constitued by the combination of two alternating and complementary events. One knows that in the relation of opposition, Yin as Yang each of them carries within himself or herself the germ of the other. (Không có gì hoàn toàn âm hoặc hoàn toàn dương, trong âm có dương và trong dương có âm). Yin and Yang are like a wheel in motion. By coming at their end, they must start again. Once their limit is reached, they go come back again. A lot of popular sayings evoking the law of causality, concretely testify to the Yin and Yang mutation.

That is why one is accustomed to saying in Vietnamese « Trong cái rũi có cái may » (In the bad luck, there will have the chance), « Trong cái dỡ có cái hay (In what appears to be bad, one also finds something good) »,« Trong họa có phúc ( In the misfortune , there will have the happiness) ». « Sướng lắm khổ nhiều (The more one is satisfied by desire, the more one will suffer ) », «Trèo cao ngã đau ( The more one climbs high, the more one has a painful drop)». « Yêu nhau nhiều cắn nhau đau. The more we are in love, the more we hurt each other’s feelings». The lost goods sometimes are the price of life. There is what the Vietnamese saying clearly expresses: Của đi thay người ( Goods are going out in the place of people). The factors Phúc and Họa have to vary in opposite directions. It’s because of the bipolarity Yin and Yang that the Vietnamese are accustomed to strike a good balance in the daily life. They try to look for a perfect arrangement with everyone and nature and even beyond their death. There is what one discovers in the necropolis of Lạch Trương (Thanh Hóa) dating from three centuries before J.C. with wooden burial objects (Yang) placed in the northern direction and that in terracotta (Yin) at the southern direction (Yang). This equilibrium notion is even found in pagoda with geniuses of good and evil. (Ông Thiện Ông Ác). It’s thanks to this equilibium philosophy that the Vietnamese have the ability to adapt to any situation, even in the extreme case. It’s also this principle of balance that Vietnamese leaders have continued to keep in the past during the confrontation with foreign countries. For avoiding the humiliation of the Mongols twice defeated in Vietnam, General Trần Hưng Đạo proposed to pay tribute to Koubilai Khan in exchange for lasting peace. After defeating the Ming, the strategist and advisor of Lê Lơi king, Nguyễn Trải did not hesitate to let Wang Toung ( Vương Thông ) come back in China with 13000 captured soldiers and proposed a pact of vasselage with a triannual toll of two fine metal statues in standard size as compensation for two generals died in combat. Likewise, Quang Trung king, guided by humility, sent an emissary to seek peace with Qianlong emperor after defeating the Qing army at Hànội in 1788 for a very short period of time.(6 days). One cannot forget the conducting and flexibility carried out by communist leaders in diplomacy during the confrontation with the French and Americans. The Geneva (1954) and Paris (1972) agreements once more testify of the search for balance or the middle way that the Vietnamese have found with ingenuity in the Yin and Yang theory. In Vietnam, the circular shaped objects (hình tròn) are integrated in the Yang and square shaped objects (hình vuông) in the Yin. It is the tendancy dating back to the period when one believed that the sky was round and the soil square and flat. The Vietnamese were obliged to square the latter before using it in the plowing and house construction. It is in the state of mind that the Bai Yue ( to which the Proto-Vietnamese belonged ) had the habit of dividing a portion of land into nine lots by taking for model the character 井 tĩnh (giếng nước). The central lot was expected for the construction of a water well and eight remaining lots were destined for the housing construction, which is the first housing unit in the agricultural society. The following Vietnamese popular saying: trời xanh như tán lọng tròn ; đất kia chằn chặn như bàn cờ vuông (The blue skue ressembles a round parasol as this perfect soil similar to the square chessboard ) reflects this popular belief. NEXT (More reading Part 2)

Bibilography

–Alain Thote: Origine et premiers développements de l’épée en Chine.

–Cung Ðình Thanh: Trống đồng Ðồng Sơn : Sự tranh luận về chủ quyền trống đồng giữa học giã Việt và Hoa.Tập San Tư Tưởng Tháng 3 năm 2002 số 18.

-Brigitte Baptandier : En guise d’introduction. Chine et anthropologie. Ateliers 24 (2001). Journée d’étude de l’APRAS sur les ethnologies régionales à Paris en 1993.

-Nguyễn Từ Thức : Tãn Mạn về Âm Dương, chẳn lẻ (www.anviettoancau.net)

-Trần Ngọc Thêm: Tìm về bản sắc văn hóa Việt-Nam. NXB : Tp Hồ Chí Minh Tp HCM 2001.

-Nguyễn Xuân Quang: Bản sắc văn hóa việt qua ngôn ngữ việt (www.dunglac.org)

-Georges Condominas : La guérilla viêt. Trait culturel majeur et pérenne de l’espace social vietnamien, L’Homme 2002/4, N° 164, p. 17-36.

-Louis Bezacier: Sur la datation d’une représentation primitive de la charrue. (BEFO, année 1967, volume 53, pages 551-556) …..