Thập Tam Lăng nhà Minh

Ming Shisan Ling

Version française

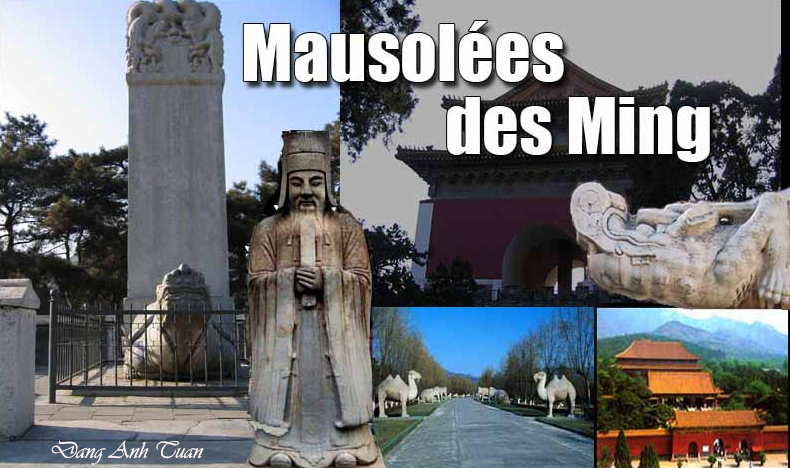

Mười ba lăng mộ nhà Minh nằm trong một thung lũng rộng phía nam núi Thiên Thọ, cách Bắc Kinh khoảng 42 cây số. Thung lũng này được chọn vì đáp ứng được tiêu chí về Phong Thủy. Nó được bao bọc ba mặt ở phía bắc nhờ có một dãy núi còn về phía nam nhờ sự hiện diên một khe hở để tránh được các thần linh ma quỷ từ gió bắc mang đến. Tổng cộng có 13 trong số 16 hoàng đế của nhà Minh, 23 hoàng hậu, một phi tần nhất phẩm cùng một số phi tần được an nghỉ tại nơi thung lũng bình yên này. Có ba vị hoàng đế nhà Minh không được chôn cất ở nơi nầy. Nằm ở trung tâm nghĩa trang, thì có ngôi mộ của Chu Đệ (Trường Lăng) được xem là nổi bật với kích thước to lớn so với mười hai lăng mộ khác. Nó cũng là ngôi mộ đầu tiên được xây dựng ở đây với 60 cột gỗ lim cao có 12 mét và có đường kính 1 mét được đưa từ vùng rừng sâu của Vân Nam và Tứ Xuyên mang về Bắc Kinh và cũng là nơi tổ chức mọi hoạt động cúng tế. Còn các ngôi mộ khác của các hoàng đế nhà Minh thì được sắp xếp theo mô hình cây quạt xung quanh con đường chính thiêng liêng được gọi là « Thần Đạo » (Shendao)

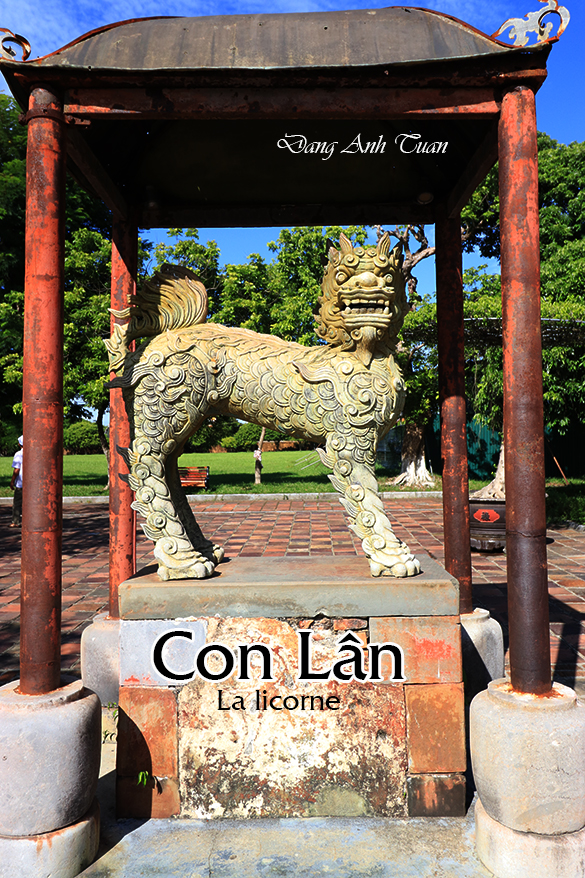

Dọc hai bên của con đường dài này thì có 36 bức tượng bằng đá, 12 vị quan chức dân sự và quân sự, và 12 cặp động vật (sư tử, lạc đà, kỳ lân, voi, ngựa và con vật tưởng tượng). Ngôi mộ của Vhu Đệ (Yong Le) vẫn còn nguyên vẹn. Nhưng chúng ta cũng biết rằng khi ông được an táng, có 16 phi tần cũng bị chôn sống. Phong tục dã man này đã bị bãi bỏ sau đó vào thế kỷ 15 dưới thời vua Minh Thần Tông (Vạn Lịch).

Khi còn sống, Hoàng đế Vạn Lịch bắt đầu xây dựng Định Lăng vào năm 1584. Điều này khiến nhà nước tốn một khoản tiền đáng kể. Không biết cấu trúc bên trong của ngôi mộ này, giáo sư Xia Nai, giám đốc Viện Khảo cổ học Bắc Kinh phải thực hiện cuộc khảo sát đầu tiên về Định Lăng vào năm 1956 và phát hiện ra ngôi mộ nầy chưa bao giờ bị xâm phạm. Chính nhờ một thẻ bài mới biết ra vị trí của cánh cửa ở trong bức tường với cơ chế bí mật được chôn sâu khoảng chừng 11 thước dưới lòng đất, ông mới thành công trong việc mở được ngôi mộ này cũng như các căn phòng phụ của nó.

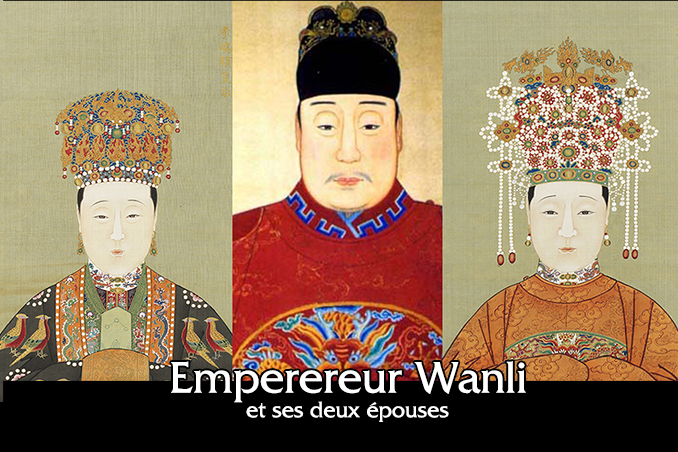

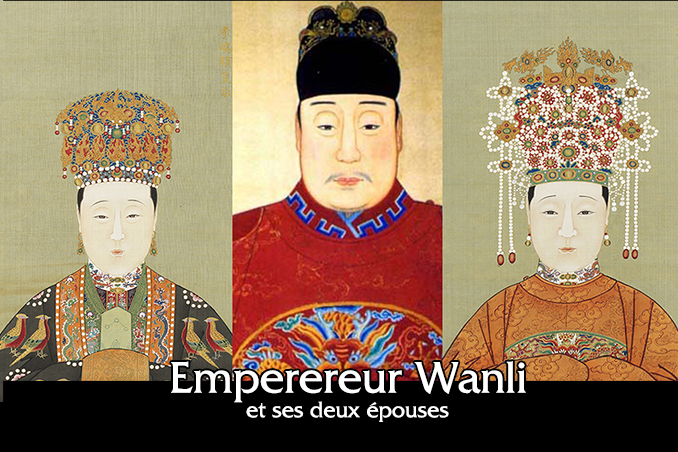

Điều này dẫn đến sự tìm thấy phòng chôn cất của Vạn Lịch và hai bà hoàng hậu Tiêu Duẩn và Tiêu Cảnh. Ngoài ra còn có một số lượng lớn các đồ vật quý giá (trang sức bằng ngọc bích, gốm sứ ba màu, meiping (một lọại bình sứ ) vân vân ) trong 26 chiếc rương sơn mài màu đỏ tía được cất giử ở phòng phía sau cùng.

Điều này dẫn đến sự tìm thấy phòng chôn cất của Vạn Lịch và hai bà hoàng hậu. Ngoài ra còn có một số lượng lớn các đồ vật quý giá (trang sức bằng ngọc bích, gốm sứ ba màu, meiping (một lọại bình sứ ) vân vân ) trong 26 chiếc rương sơn mài màu đỏ tía được cất giử ở phòng phía sau cùng. Hiện tại, ngôi mộ duy nhất mà có thể du khách được truy cập đó lăng của Wanli (1573-1620) (Vạn Lịch). Bà hoàng hậu (Hiếu Đoan Văn Hoàng hậu) và bà hoàng quí phi (Hiếu Tĩnh Hoàng hậu) được chôn cất bên cạnh hoàng đế.

Cung điện dưới lòng đất nầy có diện tích 1195 thước vuông, sâu 27 mét. Nó được có 5 phòng: phòng phía trước, phòng trung tâm, phòng phía sau cũng như hai phòng bên. Nó được xây dựng bởi 30.000 công nhân sau sáu năm. Phòng trung tâm và phòng phía trước tạo thành một hành lang dài vuông góc với phòng phía sau. Tất cả các phòng đều được ngăn cách với nhau bằng một cánh cửa lớn bằng đá cẩm thạch màu trắng được trang trí bằng những tác phẩm điêu khắc tinh xảo. Ngoài ra còn có 3 chiếc ngai bằng đá cẩm thạch dành riêng cho người đã khuất ở gian giữa.

Ngoại trừ tấm bia mộ của Chu Đệ mà người kế vị ông để lại hơn 3000 chữ ca ngợi công đức của cha mình, chúng ta không tìm thấy chữ viết nào trên tấm bia của các ngôi mộ khác. Đây là một bí ẩn mà các nhà sử học cần phải giải quyết. Một số người cho rằng các hoàng đế nhà Minh đã bãi bỏ tục lệ này vì sợ bị hậu thế chỉ trích, chế giễu vì hành vi sai trái, trụy lạc. Một số người khác lại ủng hộ sự chấp nhận thái độ của Vũ Tắc Thiên thời nhà Đường bởi các hoàng đế nhà Minh. Bà nầy không để lại dấu vết gì cả để khỏi bị chỉ trích vì bà biết cách cư xử của mình không thể hoàn hảo.

Version française

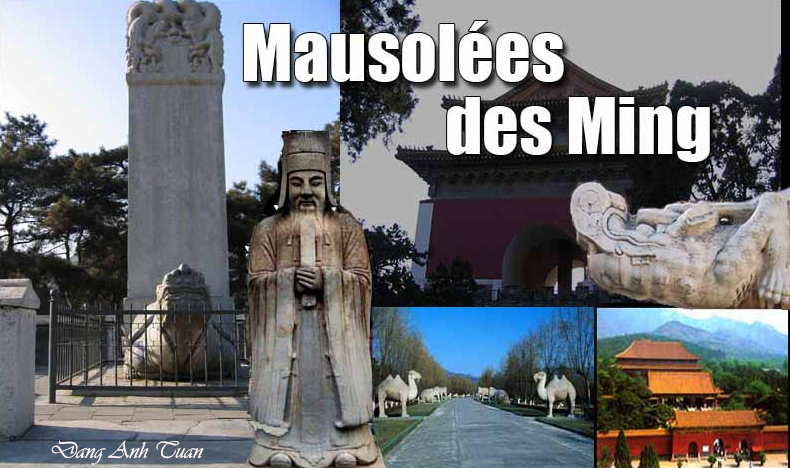

Les tombeaux des Ming sont situés dans une large vallée au sud de la montagne Tianshou (Thiên Thọ) loin de Pékin à peu près de 42 kilomètres. Cette vallée a été choisie car elle répond aux critères de Fengshui (Phong Thủy). Elle est encadrée au nord sur ses trois côtés par une chaîne de montagnes et au sud par une ouverture, ce qui lui permet d’être protégée contre les mauvais esprits emmenés par les vents du Nord. Il y a en tout 13 des 16 empereurs des Ming, 23 impératrices, une concubine de premier rang et une douzaine de concubines impériales qui ont reposé dans cette vallée paisible. Trois empereurs des Ming ne sont pas enterrés ici.

Située au centre du cimetière, la sépulture de Yong Le (Trường Lăng) se fait remarquer par sa taille imposante par rapport aux douze autres mausolées avec 60 colonnes en bois de fer (gỗ lim) ayant 12 mètres de haut et un diamètre d’un mètre, ramenés de la région forestière de Yunnan et Sichuan jusqu’à Pékin. Elle est aussi la première à y être construite. Les autres tombeaux des empereurs des Ming sont disposés en éventail autour de la voie principale sacrée (Shendao). Cette longue allée est bordée de 36 statues de pierre, 12 dignitaires civils et militaires et 12 paires d’animaux (lions, chameaux, licornes, éléphants, chevaux et chimères). Le tombeau de Yong Le est resté inviolé. Mais on sait qu’au moment de son enterrement, 16 concubines furent emmurées vivantes à son côté. Cette coutume fut abolie après au XVème siècle.

De son vivant, l’empereur Wan Li commença à construire en 1584 son tombeau Dingling (tombeau de la tranquillité)(Định Lăng). Celui-ci coûte une somme considérable à l’état. Ignorant la structure interne de ce tombeau, le professeur Xia Nai, directeur de l’institut d’archéologie de Pékin, effectua le premier sondage sur le Dingling en 1956 et découvrit ce tombeau inviolé. Grâce à une tablette indiquant l’emplacement de la porte du mur au mécanisme secret enfoui à trente cinq pieds sous terre, il réussit à ouvrir ce tombeau ainsi que ses chambres annexes. Cela permet de retrouver la chambre funéraire de Wanli et de ses 2 impératrices Xiao Duan et Xiaojing. On trouve également un grand nombre d’objets précieux (parures de jade, des céramiques à trois couleurs, des meiping etc. ) dans les 26 coffres en laque pourpre rangés dans la salle du fond. Pour le moment, le seul tombeau accessible aux visiteurs est celui de Wanli ( 1573-1620) (Vạn Lịch en vietnamien). L’impératrice et la première concubine impériale (Hoàng Qúi Phi) furent enterrées à leur mort au côté de l’empereur.

Le palais souterrain d’une superficie de 1195 m2 se trouve à 27 mètres de profondeur. Il est constitué de 5 salles: la salle antérieure, la salle centrale, la salle postérieure ainsi que deux salles latérales. Il a été construit par 30.000 ouvriers au bout de six ans. La salle centrale et la salle antérieure forment un long couloir directement perpendiculaire à la salle de fond. Toutes les salles sont isolées les unes des autres par une grande porte en marbre blanc décorée de fines sculptures. On trouve aussi 3 trônes en marbre réservés pour les défunts dans la chambre centrale.

Excepté le stèle du tombeau de Yong Le sur lequel son successeur a laissé plus de 3000 mots vantant les mérites et les vertus de son père, on ne trouve aucune écriture sur les stèles des autres tombeaux. C’est une énigme à élucider pour les historiens. Certains pensent que les empereurs des Ming abolirent cette tradition par peur d’être critiqués et ridiculisés par la postérité à cause de leur mauvaise conduite et de leur débauche. D’autres penchent en faveur de l’adoption de l’attitude de Wu Ze Tian (Vũ Tắc Thiên) de la dynastie des Tang par les empereurs des Ming. Celle-ci ne laisse aucune trace écrite afin de ne pas être critiquée car elle savait que son comportement n’était pas irréprochable.