Version française

Mois : mars 2018

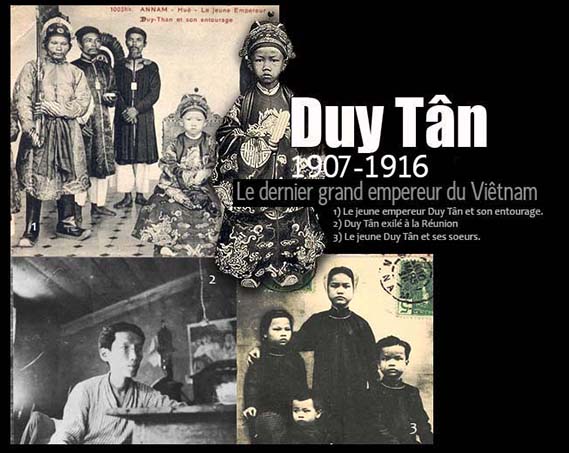

Duy Tân (1907-1916) (English version)

A great homage to the man who has dedicated all his life for his people and his country.

Một đời vì nước vì dân

Vĩnh San đứa trẻ không cần ngôi vua

Tù đày tử nhục khi thua

Tử rồi khí phách ông vua muôn đời

With the agreement of the Vietnamese authorities, the ashes of emperor Duy Tân interred up to now in the Republic of Central Africa were gathered with great pomp on April 4th, 1987 in Huế, the city of imperial mausoleums of the Nguyen dynasty. This has brought an end to a long and painful banishment that has had prince Vĩnh San often known as Duy Tân ( or Friend of Reforms ) since his uprising plan against the colonial authorities was discovered on May 4, 1916 because of the treason of a collaborator, Nguyễn Ðình Trứ.

Duy Tân is an outstanding character that none of the last emperors of the Nguyễn dynasty could be equal to. One can only regret his sudden disappearance due to a plane crash that took place at the end of 1945 on his way back from a mission from Vietnam. His death continues to feed doubt and remains one of the mysteries not elucidated until today. One found in him at that time not only the unequal popularity he knew how to acquire from his people, the royal legitimacy, but also an undeniable francophile, an alternative solution that general De Gaulle contemplated to propose to the Vietnamese at the last moment to counter the young revolutionary Hồ Chí Minh in Indochina. If he had been alive, Vietnam probably would not have known the ill-fated decades of its history and been the victim of the East-West confrontation and the cold war.

It is a profound regret that every Vietnamese could only feel when talking about him, his life and his fate. It is also a misfortune for the Vietnamese people to have lost a great statesman, to have written their history with blood and tears during the last decades.

His ascension to the throne remains a unique occurrence in the Annals of history of Vietnam. Taking advantage of suspicious anti-french schemes and the disguised lunacy of his father, emperor Thành Thái, the colonial authorities compelled the latter to abdicate in 1907 and go into exile in the Reunion at the age of 28. They requested that Prime Minister Trương Như Cường assume the regency. However this one while categorically refusing this proposal, kept demanding the colonial authorities to strictly respect the definite agreement in the Patenôtre Treaty of Protectorate (1884) providing that the throne comes back to one of the emperor’s sons in case he ceases reigning ( Phụ truyền tử kế ). Facing popular opinion and the infallible fidelity of Trương Như Cương to the Nguyen dynasty, the colonial authorities were forced to choose one of his sons as emperor. They did not hide their intention of choosing the one that seemed docile and without caliber. Except Vĩnh San, all of about 20 other sons of emperor Thành Thái were present at the moment of selection made by the General Resident Sylvain Levecque. The name Vĩnh San missed at the roll-call, which forced everyone to look for him everywhere.

Finally he was found under the beam of a frame, his face covered with mud and soak with sweat. He was chasing the crickets. Seeing him in this sordid condition, Sylvain Levecque did not hide his satisfaction because he thought only a fool would choose the day of ascession to the throne to go chasing the crickets. Upon the recommendation of his close collaborator Charles, he decided to designate him as emperor of Annam as he found in front of him a seven-year old child, timid, reserved, having no political ambition and thinking only to devote himself to games like children of his age. It was an erroneous judgment as stated in the comment of a French journalist at that time in his local newspaper:

A day on the throne has completely changed the face of an eight-year old child.

One noticed a few years later that the journalist was right because Duy Tân has dedicated all his life for his people and his country until his last breath of life.

At the time of his ascension to the throne he was only 7. To give him a stature of an emperor, they had to give him one more year of age. That is why in the Annals of history of Vietnam, he was brought to the throne at 8 years of age. To deal with this erroneous designation, the colonial authorities installed a council of regency constituted of Vietnamese personalities close to General Resident Sylvain Levecque ( Tôn Thất Hân, Nguyễn Hữu Bài, Huỳnh Côn, Miên Lịch, Lê Trinh, Cao Xuân Dục) to assist the emperor in the management of the country and requested that Eberhard, the father-in-law of Charles be Duy Tân’s tutor. It was a way to closely supervise the activities of this young man.

In spite of that, Duy Tân succeeded in evading the surveillance network placed by the colonial authorities. He was one of the fierce partisans for the revision of the Patenotre agreements (1884). He was the architect of several reforms: Tax and chore duty reduction, elimination of wasteful court protocols, reduction of his own salary etc… He forcefully protested the profanation of emperor Tự Ðức’s tomb by General Resident Mahé in his search for gold, with the governor of Indochina Albert Sarraut. He claimed the right to look at the management of the country. This marked the prelude of dissension which grew more and more visible between him and the French Superior Resident. On May 4, 1916, with Trần Cao Vân and Thái Phiên, he fomented a rebellion which was discovered and put down due to the treason of one of his collaborators. Despite his capture and flattering advice of the Governor of Indochina asking him to reexamine his comportment and conduct, he continued be impassible and said:

If you compelled me to remain emperor of Annam, you should consider me as an adult emperor. I should need neither the council of regency nor your advice. I should manage the country’s business on the same footing with all foreign countries including France.

Facing his unwavering conviction, the colonial authorities had to assign the Minister of Instructions of that time, the father-in-law of future emperor Khải-Ðịnh, Hồ Ðắc Trung to institute proceedings against his treason toward France. For not compromising Duy Tân, the two older collaborators Trần Cao Vân and Thái Phiên made it known to Hồ Đắc Trung their intent to voluntarily accept the verdict provided that emperor Duy Tân was exempt from the capital punishment. They kept saying:

The sky is still there. So are the earth and the dynasty. We wish long live to the emperor.

Faithful to the Nguyen dynasty, Hồ Ðắc Trung only condemned the emperor to exile in justifying the fact that he was a minor and that the responsibility of the plot rested with the older collaborators Trần Cao Vân and Thái Phiên.

The men were guillotined at An Hoà. As for emperor Duy Tân, he was condemned to exile to the Reunion on November 3, 1916 on board of the steamship Avardiana. The day before his departure, the representative of the General Resident visited him and asked:

Sir, if you need money you may take it from the state coffer.

Duy Tân replied politely :

The money that you find in the coffer is intended to help the king to govern the country but it does not belong to me in anyway especially to a political prisoner.

To entertain the king, the representative did not hesitate to remind him that it was possible to choose preferred books in the library and take them with him during his exile because he knew the king loved to read very much. He agreed to that proposal and told him:

I love reading very much. If you have the chance to bring books for me, don’t forget to bring the entirety of all the volumes of « History of the French Revolution » of Michelet.

The representative dared not report to the Resident what Duy Tan had told him.

His exile marked not only the end of the imperial resistance and the struggle monopolized and animated up until then by the scholars for the defense of the Confucian order and the imperial state but also the beginning of a national movement and the emergence of a state nationalism placed in birth by the great patriot scholar Phan Bội Châu. It was also a lost chance for France for not taking the initiative to give freedom to Vietnam in the person of Duy Tân, a francophile of the first hour.

His destiny is that of the Vietnamese people. For a certain time, one has deliberately made all streets bearing his name disappear in big cities ( Hànội, Huế, Sàigon ) in Vietnam, but one cannot forever erase his cherished name in his people’s heart and in our collective memory. He is not the rival of anybody but he is on the contrary

the last great emperor of Vietnam.

To this title I dedicate to him the following four verses:

Devoting his whole life to his country and people,

Duy Tan the kid did not hang on to his throne.

Facing exile and humility when defeated,

His uprightness lives forever in history unabated.

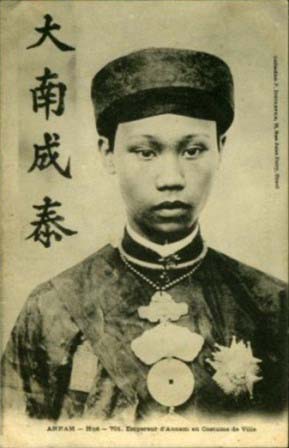

Thành Thái (1879-1954) (English version)

Thành Thái

A great homage to a man who devoted his whole life for his country and people through my Six-Eight verses:

Ta điên vì nước vì dân

Ta nào câm điếc một lần lên ngôi

Trăm ngàn tủi nhục thế thôi

Lưu đày thể xác than ôi cũng đành

His madness for the love of his country and people.

I am mad for the love of my country and people

Once on the throne, I can’t stay deaf-mute

It wouldn’t matter I feel self pity and shame

And my body suffers years of exile with resignation

Prior to becoming emperor Thành Thái, he was known as Bửu Lân. He was the son of emperor Dục Ðức who had been vilely assassinated by the two Confucianist mandarins Tôn Thất Thuyết and Nguyễn Văn Tường, and the grand son of the mandarin Phan Ðình Bình. Because the latter was maladroitly opposed to the enthronement of emperor Ðồng Khánh by the colonial authorities, Ðồng Khánh was fast to take revenge by cowardly getting rid of this old mandarin and by putting Bửu Lân and his mother under house surveillance within the surrounding wall of the purple city at the Trần Võ palace in order to avoid all seeds of revolt. That was why at Ðồng Khánh’s death and upon the announcement of the choice of her son as the successor by the colonial authorities, Buu Lan’s mother was surprised and cried so much because she was always obsessed by the idea that her son would probably meet the same fate as her husband, emperor Dục Đức and her father, the mandarin Phan Ðình Bình. If Buu Lan was preferred to other princes, it was incontestably due to the ingenuities of Diệp Văn Cương, the presumed lover of his aunt, princess Công Nữ Thiên Niệm because Diệp Vân Cương was Resident General Rheinart‘s personal secretary, in charge of conducting business with the Imperial Court to find a compromise on the person to be chosen to succeed emperor Ðồng Khánh.

Thus he involuntarily became our new emperor known as Thành Thái. He was fast to realize that his power was very limited, that the Patenôtre treaty was never respected and that he had no right with regard to the management and future of his country. Contrary to his predecessor Ðồng Khánh, close to the colonial authorities, he took a passive resistance by trying to thwart their policies in a systematic manner with his provoking remarks and amicable gestures. His fist virulent altercation with the Resident General Alexis Auvergne was noticed at the inaugural ceremony of the new bridge spanning across the Perfume river. Proud of technical prowess and confident of the sturdiness of the bridge, Alexis Auvergne did not hesitate to tell Thành Thái with his habitual cynicism:

When you would have seen this bridge collapse, your country would be independent.

To show the importance that the colonial authorities has given to the new bridge, they named it « Thành Thái ». This made the emperor mad. Using as a pretext that everyone can walk over his head when crossing the bridge, he forbade his subjects to call the bridge by its new name and incited them to use the old name « Tràng Tiền ».

Some years later, the bridge collapsed during a violent storm. Thành Thái was fast to recall Alexis Auvergne of what he had said with his black humor. Alexis Auvergne was red with shame and had to clear off at these embarrassing remarks. The dissension with the authorities grew day by day until the replacement of the old Resident General by Sylvain Levecque. The latter was fast to place a network of strict surveillance when he learned that Thanh Thai continued to approach his people through the bias of his reforms and his disguise in plain clothes or as a beggar in villages. He was the first emperor of Vietnam to take the initiative of having his hair cut the European fashion, which astonished so many of his mandarins and subjects when he first appeared. But he also was the first emperor to encourage his subjects to follow French education. He was the artisan of several architectural projects. He was also the first emperor of the Nguyen dynasty who wanted to pay enormous attention to the daily life of his subjects and to know their daily difficulties. It was reported that during an escorted excursion, he met on his way a poor man who was hauling a heavy load of bamboo. He body guard wanted to ease the way but he stopped him by saying:

I am neither citizen nor emperor as I should be in this country. Why do you chase him away?

During his excursions, he often used to sit on a mat, surrounded by the villagers and to discuss all the issues with them. It was in one of his excursion that he brought back to the purple city an oarswoman who accepted to marry him and became his concubine. He was well known as an excellent drummer.

That is why he summoned all the best drummers in the country to the purple city, asked them to play drums before his court and reward them generously according to their merit. It was reported that one day, he met a drummer who used to tilt his head when playing. Wanting to help him correct this funny habit, he told him jokingly:

If you keep on playing that way, I will have to have your head rolled.

From then on, the drummer, worrying incessantly about the next call, was overwhelmed by fear and died of a heart attack. One day, knowing the death of the drummer, Thanh Thai was taken my remorse, summoned his family and gave them a large sum of money to take care of their daily needs.

His way of joking, his frequent disguises, his sometimes strange behavior incomprehensible to the colonial authorities gave them an opportunity to brand him a lunatic.

As for Thành Thái, he was deported first to Vũng Tàu (former Cap St. Jacques) in the Fall of 1907, then later to the Reunion Island with his son, emperor Duy Tân in 1916. He was only allowed to return to Vietnam in 1945 after the death of Duy Tân and to stay confined within Vũng Tàu, South Vietnam during the last years of his life.

Is it possible to brand him lunatic when it is known through his poem titled « Hoài Cổ » ( Remember the Past ) that Thành Thái was so lucid and never stopped to groan with the pain facing the alarming situation of his country? Other eight seven-foot verses we know such as The storm of the year of the Dragon in 1904 ( Vịnh Trần Bão Năm Thìn ) or Profession of Faith ( Cảm Hoài ) not only show Thành Thai’s perfect mastery in the strict application of the difficult rules in Vietnamese poetry but also the painful pride of a great emperor who, in spite of a forced exile for almost half a century ( 1907-1954 ) by the colonial authorities, continued to display his conviction and unshakable faith in the liberation of his country. Through him it is already seen forging on this land of legends the instruments of a future revolt.

For him, his incurable illness was the goal to realize his intention, to give his people the dignity so long waited and to show future generations the sacrifice and the price which even he, a person considered alienated by the colonial authorities, had to pay for that country ( 47 years of exile ). In the political context of the time, he should not reveal himself of this « illness ».

Up to now, no historic document show us Thành Thái’s insanity but rather it reveals a great emperor’s lunacy of the love of his country and people, neverending affliction of a great patriot facing the destiny of his country.

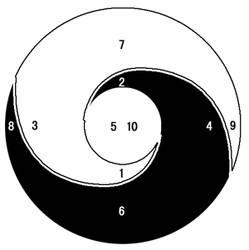

Yin and Yang numbers (Âm Dương: Part 3)

Yin and Yang numbers (Con số Âm Dương)

One is accustomed to say in Vietnamese: sống chết đều có số cả (Everyone has his D day for life and death). Ði buôn có số, ăn cỗ có phần (One has his vocation in trade as one has his part in feast). In daily life, everyone a his size for his clothing and his shoes. Contrary to the Chinese, the Vietnamese emphasize odd numbers (số dương) rather than even numbers (sô’ âm).

One frequently finds the use of even numbers in the Vietnamese phrases: ba mặt một lời (One needs to be in front of someone with the presence of a witness), ba hồn bảy vía ( three souls and 7 vital supports for men i.e one is terrified), Ba chìm bảy nổi chín lênh đênh ( very hectic), năm thê bảy thiếp ( to have 5 spouses and 7 concubines i.e. to have many women ), năm lần bảy lượt ( many times), năm cha ba mẹ ( heterogenuos), ba chóp bảy nhoáng ( with precipitation and no care ), Môt lời nói dối , sám hối 7 ngày (A speech deceitful amounts to seven days of repentance), Một câu nhịn chín câu lành (To avoid an offensive sentence is having kind sentences ) etc …or that of integral multiples of the number 9:18 (9×2) đời Hùng Vương ( 18 legendary kings Hùng Vương ), 27 (9×3) đại tang 3 năm (27 tháng)(or a beareavement endured on three years or 27 months only), 36 (9×4) phố phường Hànội (Hànội with 36 neighbourhoods) etc …One don’t forget to mention the numbers 5 and 9, having each of them a role very important. The figure 5 is the number the most mysterious because all starts from this number. Heaven and Earth have the five elements or agents giving birth to thousand things and objects. It is placed in the center of the River map and Writings of Luo which are the basis for the mutation of five elements (Thủy, Hỏa, Mộc, Kim, Thổ)( Water, Fire, Wood, Metal and Earth). It is associated to the element Earth in the central position that the peasant needs to known for the management of cardinal points. This goes to the man to have the centre in the management of things and species and four cardinals. That is why, in the feudal society, this place is reserved to the king because it is he who has govern the people. Consequently, the number 5 belonged to him as well as the yellow colour symbolizing the Earth. This explains the colour choosen by Vietnamese and Chinese emperors for their clothes.

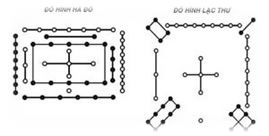

Ho Tou Lo Chou

(Hà Đồ Lạc Thư)

In the addition to the centre occupied by man, an symbolic animal is associated to the each of four cardinal points: the North by the turtle, the South by the phoenix, the West by the dragon and the East by the tiger. One is’nt surprised to see at least in this attribution the presence of three animals living in the region where the agricultural life plays a notable role and water is vital. It is the land of Bai Yue group. Even the dragon very mean in others cultures becomes a kind and noble animal imagined by peaceful peoples Bai Yue. The number 5 is yet known under the name « Tham Thiên Lưỡng Đia » (or three Heaven two Earth or 3 Yang 2 Yin) in the Yin and Yang theory because the acquisition of the number 5 coming from the union of numbers 3 and 2 corresponds better to the reasonable percentage of Yin and Yang than that of the association of numbers 4 and 1. In this latter, the number Yang 1 very dominated by the number 4. It is’nt the case of the union of the numbers 3 and 2 because the number Yang 3 slightly overpowers the number Yin 2. This encourages the universe development in an almost perfect harmony. In ancient times, the fifth day, the fourteen en day (1+4=5) and the twenty-third (2+3=5) day in the month were reserved for the way out of the king. It is’nt allowed to subjects for trading during his travel and disturbing his walk. It is perhaps the reason for which a great number of the Vietnamese continue to avoid these days for the home construction, the trip and major purchases. One is accustomed to say:

Chớ đi ngày bảy chớ về ngày ba

Mồng năm, mười bốn hai ba

Đi chơi cũng lỗ nữa là đi buôn

Mồng năm mười bốn hai ba

Trồng cây cây đỗ, làm nhà nhà xiêu

You avoid going out the 7th day and coming back the 3th in the month. For the 15th, 14th and 23th days in the month, you will be losing if you go out or you trade. Likewise, you will see the failing tree or the tilting of your home if you make the planting tree or the house construction.

The number 5 is frequently mentioned in the Vietnamese culinary art. The most typical sauce remains the fish brine (nước mắm). In the preparation of this national sauce, one mentiones the presence of 5 flavours classified according to the 5 elements of Yin and Yang:mặn ( salty ) with the fish juice (nước mắm), đắng (bitter) with the lemon zest (vỏ chanh), chua (acidulous) with the lemon juice, cay (spicy) with pigments crushed in powder or chopped in strips and ngọt (sweet ) with sugar in powder. These 5 flavours ( mặn, đắng, chua, cay, ngọt ) combined and found in the Vietnamese national sauce correspond to 5 elements defined in the Yin and Yang theory (Thủy, Hỏa , Mộc , Kim Thổ ) ( Water, Fire, Wood, Metal and Earth ).

Likewise, one rediscovers these 5 flavours in the bittersweet soup (canch chua) prepared from fish: acidulous with tamarin seeds or vinegar, sweet with slices of ananas, spicy with pigments chopped in strips, salty with fish juice and bitter with some okras (đậu bắp) or flowers of « fayotier in French » (bông so đũa). When the soup is served, one will add some fragrant herbs like the panicaut (ngò gai), rau om (herb having the flavor of coriander with a lemony taste in addition). It is a characteristic trait of the bittersweet soup of Sud Vietnam which is different from those found in others regions of Vietnam.

One cannot forget to mentione the sweet rice cake that the Proto-Vietnamese had succeeded to bequeath to descendants over millennia of their civilization. This sweet rice cake is the intangible proof of Yin and Yang theory and 5 elements belonging to Bai Yue group (Hundred Yue), the Proto-Vietnamese of which formed part because there is the generation cycle (Ngũ hành tương sinh) in its composition.

(Fire->Earth->Metal->Water->Wood)

Inside the cake, one finds a piece of porkmeat in red color ( Fire ) around which there is a kind of paste made with broad beans in yellow color ( Earth ). The whole thing is wrapped by the sticky rice in white color ( Metal ) to be cooked with boiling water ( Water ) before having a green colouring on its surface thanks to the latanier leaves (Wood).

An other cake is not missing th weddings. This is the cake susê or phu thê (husband-spouse) having inside a round form and enveloped by banana leaves (green colour) in order to give it the well-tied cube appearance with a red ribbon (red color). The circle is thus placed within the square (Dương trong âm)(Yang in Yin). This cake is made from tapioca flour, perfumed in pandan and strewn with black sesame seeds (black color). One finds in the hearth of this cake a paste made of steamed soybeans (yellow color) and jam of lotus seeds and grated coconut.(white color). This paste is very similar to the frangipane found in « galettes des rois ». Its sticky texture reminds the link that one can represent in the union. This cake is the symbol of the perfection in conjugal love and loyalty responding the perfect agreement with the Heaven and the Earth and 5 elements symbolized by 5 colors (red, green, black, yellow and white).

This cake is related by the following tale: in the past, there was a merchant engaged in debauchery and doing not like to go home although before his departure, his spouse gave him the cake susê and promised to remain cordial and sweet like the cake. That is why, when she has heard this story, she did send others cakes phu thê accompagnied by two following verses:

Từ ngày chàng bước xuống ghe

Sóng bao nhiêu đợt bánh phu thê rầu bấy nhiêu

Since your departure, waves were encountered by your boat as much as afflictions were known by the cake susê

Lầu Ngũ Phụng

In architecture, the number 5 is not forgetten either. It is the case of Ngọ Môn gate (noon gate) in the forbidden city (Huế). This gate is a powerful masonry foundation drilled with five passages and surmonted by an elegant wooden structure with two levels, the Belvedere of five Phoenixes (Lầu Ngủ Phụng). Viewed from the sky, this latter with two additional wings, seems to form five phoenix in flight with intertwined beaks. This belvedere possesses 100 wood columns(gỗ lim)(ironwood) painted and tinted in yellow for allowing to carry its nine roofs. This number 100 was well examinated by Vietnamese specialists. According to renowned archeologist Phan Thuận An, it exactly corresponds to the total number obtained by adding two numbers found respectively in the River map (Hà Đồ) and Writings of Luo (Lạc thư cửu tinh đồ) symbolizing the perfect harmony of the union Yin and Yang. It is not the Liễu Thượng Văn advice. According to this latter, this represents the strength of 100 families or people (bách tính) and reflects the notion dân vi bản (consider people as basis) in the Nguyễn dynasty’s governance. The roof of the central pavilion is covered by yellow tiles « lưu ly », the rest being with blue tiles « lưu ly ». Being just in the middle, the main gate (or noon gate) is reserved to the king and paved with stones « Thanh » tinted in yellow color. From both sides, one finds left and right doors (Tả, Hữu, Giáp Môn) reserved to civilian and military mandarins. Then two others lateral gates Tả Dịch Môn và Hữu Dịch Môn are intended to soldiers and horses. One is accustomed to say in Vietnamese:

Ngọ Môn năm cửa chín lầu

Một lầu vàng, tám lầu xanh, ba cửa thẳng, hai cửa quanh »

The noon gate possesses 5 passages and 9 roofs the one of which is varnished in yellow and the 8 others in blue. There are three main doors and two side entries.

In the east and west of the citadel, ones finds Humanty and Virtue gates which are reserved respectively for men and women.

The number 9 is a Yang number (or odd number). It representes the Yang strength at the maximum. It is difficult to reach it. That is why, in the past, the emperor often uses for showing his power and supremacy. He climbs 9 stairs symbolizing the ascent of sacred mountain in which there was his throne. It is said that the forbidden city like that of Pékin possessed 9999 rooms. It is useful to recall that the forbidden city of Pékin was supervised by Nguyễn An, a Vietnamese exiled still young at the time of the Ming. As his palaces, the emperor turns towards the South in Yang energy in order to receive the vital breath of Sky because he is the Heaven son. In Vietnam, one finds nine dynastic urns of Huế citadel, nine branchs of Mekon river, nine roofs of Belvedere of five Phoenixes etc … In the tale intituled « The God of Mountains and the God of Rivers « (Sơn Tinh Thủy Tinh) », 18th (2×9) Hùng Vương king, proposed for the dowry marriage of his daughter Mị Nương: an elephant with nine tusks, a rooster with nine spurs and a horse with nine red manes. The number 9 symbolizes the Heaven, the birthday of which is the ninth (9th) day of February month.

Being less important than 5 and 9, the number 3 (or Ba and Tam in Vietnamese) isclosely tied to the daily life of the Vietnamese. They do not hesitate to evoke it in a large number of popular expressions. For meaning a certain limit, a certain degree, they have the habit of saying:

Không ai giàu ba họ, không ai khó ba đời:

No person can claim to be rich to three generations as no one is more stringent to three successive lives.

It goes to the Vietnamese to often accomplish this certain thing at once, this obliges them to do many times this operation. It is the following expression that they uses frequently: Nhất quá tam. It is the number 3, a limit they don’t like to exceed in the accomplishment of this task. For saying that someone is irresponsible, they designate him under the term “Ba trợn“. Someone who is opportunistic is called « Ba phải » . The expression « Ba đá » is reserved to vulgar people while those who continue to be entangled in minor matters or endless difficulties receive the title « Ba lăng nhăng« . For weighing his words, the Vietnamese needs to bend three inches of his tongue. (Uốn ba tấc lưỡi).

The number 3 also is synonymous with insignificant and unimportant something.It is what one finds in following popular expressions:

Ăn sơ sài ba hột: To eat a little bit.

Ăn ba miếng: idem

Sách ba xu: book without values. (the book costs only three pennies).

Ba món ăn chơi: Some dishes for tasting.

Analogous to number 3, the number 7 is often mentioned in Vietnamese literature. One cannot ignore either the expression Bảy nỗi ba chìm với nước non (I float 7 times and I descend thee times if this expression is translated in verbatim) that Hồ Xuân Hương poetess has used and immortalized in her poem intituled « Bánh trôi nước” :

Thân em vừa trắng lại vừa tròn

Bây nỗi ba chìm với nước non

……….

for describing difficulties encountered by the Vietnamese woman in a feudal and Confucian society. This one did not spare either those having an independent mind, freedom and justice. It is the case of Cao Bá Quát , an active scholar who was degusted from the scholastica of his time and dreamed of replacing the Nguyễn authoritarian monarchy by an enlightened monarchy. Accused of being the actor of the grasshoppers insurrection (Giặc Châu Chấu) in 1854, he was condemned to death and he did no hesitate his reflection on the fate reserved to those who dared to criticize the despotism and feudal society in his poem before his death:

Ba hồi trống giục đù cha kiếp

Một nhát gươm đưa, đéo mẹ đời.

Three gongs are reserved to the miserable fate

A sabre slice finishes this dog’s life.

If the Yin and Yang theory continues to haunt their mind for its mystical and impenetrable character, it remains however a way of thinking and living to which a good number of the Vietnamese continue to refer daily for common practices and respect of ancestral traditions.

Bibliography

-Xu Zhao Long : Chôkô bunmei no hakken, Chûgoku kodai no nazo in semaru (Découverte de la civilisation du Yanzi. A la recherche des mystères de l’antiquité chinoise, Tokyo, Kadokawa-shoten 1998).

-Yasuda Yoshinori : Taiga bunmei no tanjô, Chôkô bunmei no tankyû (Naissance des civilisations des grands fleuves. Recherche sur la civilisation du Yanzi), Tôkyô, Kadokawa-shoten, 2000).

-Richard Wilhelm : Histoire de la civilisation chinoise 1931

-Nguyên Nguyên: Thử đọc lại truyền thuyết Hùng Vương

– Léonard Rousseau: La première conquête chinoise des pays annamites (IIIe siècle avant notre ère). BEFO, année 1923, Vol 23, no 1

-Paul Pozner : Le problème des chroniques vietnamiennes., origines et influences étrangères. BEFO, année 1980, vol 67, no 67, p 275-302

-Dich Quốc Tã : Văn Học sữ Trung Quốc, traduit en vietnamien par Hoàng Minh Ðức 1975.

-Norman Jerry- Mei tsulin (1976) : The Austro asiatic in south China : some lexical evidence, Monumenta Serica 32 :274-301

-Henri Maspero : Chine Antique : 1927.

-Jacques Lemoine : Mythes d’origine, mythes d’identification. L’homme 101, paris, 1987 XXVII pp 58-85

-Fung Yu Lan: A History of Chinese Philosophy ( traduction vietnamienne Đại cương triết học sử Trung Quốc” (SG, 1968).68, tr. 140-151)).

-Alain Thote: Origine et premiers développements de l’épée en Chine.

-Cung Ðình Thanh: Trống đồng Ðồng Sơn : Sự tranh luận về chủ quyền trống

đồng giữa h ọc giã Việt và Hoa.Tập San Tư Tưởng Tháng 3 năm 2002 số 18.

-Brigitte Baptandier : En guise d’introduction. Chine et anthropologie. Ateliers 24 (2001). Journée d’étude de l’APRAS sur les ethnologies régionales à Paris en 1993.

-Nguyễn Từ Thức : Tãn Mạn về Âm Dương, chẳn lẻ (www.anviettoancau.net)

-Trần Ngọc Thêm: Tìm về bản sắc văn hóa Việt-Nam. NXB : Tp Hồ Chí Minh Tp HCM 2001.

-Nguyễn Xuân Quang: Bản sắc văn hóa việt qua ngôn ngữ việt (www.dunglac.org)

-Georges Condominas : La guérilla viêt. Trait culturel majeur et pérenne de l’espace social vietnamien, L’Homme 2002/4, N° 164, p. 17-36.

-Louis Bezacier: Sur la datation d’une représentation primitive de la charrue. (BEFO, année 1967, volume 53, pages 551-556)

-Ballinger S.W. & all: Southeast Asian mitochondrial DNA Analysis reveals genetic continuity of ancient Mongoloid migration, Genetics 1992 vol 130 p.139-152….

Yin and Yang theory: (Âm Dương Phần 2)

By speaking of the couple circle/square, one wants to evoke the perfection and happy union. That is why one is accustomed to say in Vietnamese: « Mẹ tròn, con vuông » for wishing the mother and her child a good health a the time of birth. This expression has been bequeathed by our ancestors with the aim of retaining our attention on the creative character of universe. The roundness and square are two foms taken not only by rice cakes (Bánh Chưng, Bánh Tết) or married couple cakes (Bánh Su Sê ou Phu Thê) but also Vietnamese old coins (or copper cash pieces). The form of this latter is related to the Vietnamese traditional cosmology: their roundness evokes that of sky and the central hole is square as soil.

Old coin

For the surface of this old coins, there is always a percentage to be respected: 70% for the round part and 30% the square part. One also finds two forms with the bamboo rod held by the eldest son by walking after the coffin during the funeral procession of his father. When the deceased is his mother, he is obliged to walk backwards before the coffin. It is the protocol « Cha đưa mẹ đón» (Accompagny the father, receive the mother) to be respected in Vietnamese funeral rituals. The rod bamboo represents the father’s righteousness and endurance. It is replaced by an other plant known under the name « cây vong » and symbolizing the simplicity, sweetness and flexibility when the deceased is the mother. The rod must have the round head and square leg for symbolizing the Heaven and the Earth while the median part of rod is reserved for children and descendants. That means everyone needs the protection of the Heaven and the Earth, the education of parents and mutual assistance between brothers and sisters in the society. For showing the respect, the number of times which the invited person is obliged to accomplish by bending his back in the state of prostration before the coffin is a Yin number (or an even number)(i.e. 2 or 4) because the deceased is going to the darker world of Yin nature (Âm phủ in Vietnamese). In the past, one had the habit of putting in the deceased mouth a scrap of gold in order to breathe the mana contained in the precious metal into him. Being of Yang nature, the gold is able to assume the body preservation and prevent the putrefaction. At the time of the agony of the deceased, his family members must give him a surname (or in Vietnamese tên thụy) which is known only by them with the agreement of home genius because at the anniversary of his death, this surname will be called in order to invite him to participate in offerings and avoid waking others lost souls. That is why one is accustomed to say in Vietnamese tên cúng cơm for reminding that everyone has a surname. Likewise, the bunch of flowers offered to funerals must be constituted of an even number of flowers (or Yin number).

There is an exception to this rule when one is dealing with Buddha or deceased parents. Before the altar of this later, one is accustomed to put 3 incense sticks in the vase or one gets down completely on his knees with head on ground by repeating an odder number of times (Yang number) because one always consideres them as living beings. Likewise, for showing the respect towards seniors, one only accomplishes one or three times in prostration. However, in marriage rites, the future wife must bow down before her parents for thanking them from the birth and education received before joining the family of her husband. It is an even number (or Yin number) of times she will accomplish (i.e. 2) because she is considered « dead » and does not belong to her original family. There is a custom for the ceremony of first wedding night. Being supposed to be good, honest, old enough and having many children, a woman takes charge of spreading and overlapping of a pair of mats on the nuptial bed: one of these mats is open, the other upside down in the image of Yin and Yang union.

There is an exception to this rule when one is dealing with Buddha or deceased parents. Before the altar of this later, one is accustomed to put 3 incense sticks in the vase or one gets down completely on his knees with head on ground by repeating an odder number of times (Yang number) because one always consideres them as living beings. Likewise, for showing the respect towards seniors, one only accomplishes one or three times in prostration. However, in marriage rites, the future wife must bow down before her parents for thanking them from the birth and education received before joining the family of her husband. It is an even number (or Yin number) of times she will accomplish (i.e. 2) because she is considered « dead » and does not belong to her original family. There is a custom for the ceremony of first wedding night. Being supposed to be good, honest, old enough and having many children, a woman takes charge of spreading and overlapping of a pair of mats on the nuptial bed: one of these mats is open, the other upside down in the image of Yin and Yang union.

In ancien times, young married men are accustomed to exchange mutually a pinch of earth against a pinch of salt. They would like to honour and sustain their union and fidelity by taking the Heaven and the Earth as the witnesses of their engagement. One also finds the same signification in the following expression: Gừng cay muối mặn for reminding young married men that they should not leave themselves because the life is bitter and painful with ups and downs as ginger and it is intense and deep with feelings as salt.

In ancien times, young married men are accustomed to exchange mutually a pinch of earth against a pinch of salt. They would like to honour and sustain their union and fidelity by taking the Heaven and the Earth as the witnesses of their engagement. One also finds the same signification in the following expression: Gừng cay muối mặn for reminding young married men that they should not leave themselves because the life is bitter and painful with ups and downs as ginger and it is intense and deep with feelings as salt.

For speaking of virtue, one is accustomed to say in Vietnamese:

Ba vuông sánh với bảy tròn

Đời cha vinh hiễn đời con sang giàu

As three squares can be in comparison seven circles, virtuous parents will have rich children.

By speaking of these three squares, one needs to reminder the square form of rice cake proposed during the new year. This cake constituted by straight lines symbolizes loyalty and righteousness in the relationship of three submissions « Tam Tòng »: Tại gia tòng phu, xuất giá tòng phu, phu tữ tòng tữ (submission to the father before her marriage,submission to the husband during her marriage, submission to the elder son when widowed).

About 7 circles, one must think of the roundness of « bánh giầy ». This one is constituted by a sequence of dots equidistant from the center where there is the heart. This cake is the symbol of a well-balancel soul that any passion does not bewinder. One finds in this heart the perfection of seven human sentiments: (Thất tình : hỹ, nộ, ái, lạc, sĩ, ố, dục )( Joy, anger, sadness, cheerfullness, love, hatred, desire). Does someone realize a ideal moral life if under any circumstances, he succeeds to maintain the loyalty and righteousness with others and always keeps his equidistant gap in the manifestation of his feelings?

The expression vuông tròn has frequently been employed in a great number of Vietnamese popular sayings:

Lạy trời cho đặng vuông tròn

Trăm năm cho trọn lòng son với chàng!

I pray to God that everything should go well and I should eternally keep my faithful hearth with you.

or

Đấy mà xử ngãi (nghĩa) vuông tròn

Ngàn năm ly biệt vẫn còn đợi trông

Here is the signification of conjugal love

Despite the eternal separation, one continues to wait for the return with patience

or in the following verses 411-412 and 1331-1332 of Kim Vân Kiều‘s best-seller

Nghĩ mình phận mỏng cánh chuồn

Khuôn xanh biết có vuông tròn mà haỵ

My fate is fragile like the dragonfly’s wing

Does the Heaven knows that this union is durable or not?

or

Trăm năm tính cuộc vuông tròn,

Phải dò cho đến ngọn nguồn lạch sông

During your lifetime (hundred years), when you are concerned by your marriage, you must climb up the river to the source (i. e. you must get informed in the smallest detail).

This bipolarity Yin and Yang is visible in various forms in Vietnam. In China, an only genius of marriage is seen, one has in Vietnam a couple of geniuses, a man and a woman (Ông Tơ Bà Nguyêt). Likewise, in Vietnamese pagodas, one finds on the altar a couple of Buddhas (a man and a woman) (Phât ông Phât Bà) in place of one Buddha. The Vietnamese strongly believe that each of them is associated with a certain number of digits. Before the birth, the embryo needs to wait for 9 months and 10 days. For speaking of someone having a happy destiny, one says he as the « good luck » (số đỏ). On the contrary, the » bad luck (số đen) » is reserved to people having a lamentable destiny. NEXT (Yin and Yang numbers)