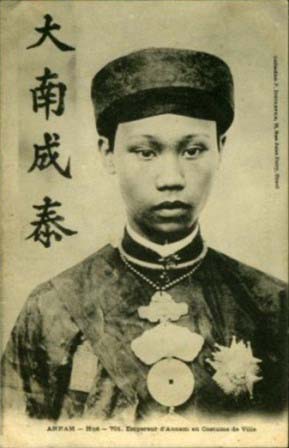

Thành Thái

A great homage to a man who devoted his whole life for his country and people through my Six-Eight verses:

Ta điên vì nước vì dân

Ta nào câm điếc một lần lên ngôi

Trăm ngàn tủi nhục thế thôi

Lưu đày thể xác than ôi cũng đành

His madness for the love of his country and people.

I am mad for the love of my country and people

Once on the throne, I can’t stay deaf-mute

It wouldn’t matter I feel self pity and shame

And my body suffers years of exile with resignation

Prior to becoming emperor Thành Thái, he was known as Bửu Lân. He was the son of emperor Dục Ðức who had been vilely assassinated by the two Confucianist mandarins Tôn Thất Thuyết and Nguyễn Văn Tường, and the grand son of the mandarin Phan Ðình Bình. Because the latter was maladroitly opposed to the enthronement of emperor Ðồng Khánh by the colonial authorities, Ðồng Khánh was fast to take revenge by cowardly getting rid of this old mandarin and by putting Bửu Lân and his mother under house surveillance within the surrounding wall of the purple city at the Trần Võ palace in order to avoid all seeds of revolt. That was why at Ðồng Khánh’s death and upon the announcement of the choice of her son as the successor by the colonial authorities, Buu Lan’s mother was surprised and cried so much because she was always obsessed by the idea that her son would probably meet the same fate as her husband, emperor Dục Đức and her father, the mandarin Phan Ðình Bình. If Buu Lan was preferred to other princes, it was incontestably due to the ingenuities of Diệp Văn Cương, the presumed lover of his aunt, princess Công Nữ Thiên Niệm because Diệp Vân Cương was Resident General Rheinart‘s personal secretary, in charge of conducting business with the Imperial Court to find a compromise on the person to be chosen to succeed emperor Ðồng Khánh.

Thus he involuntarily became our new emperor known as Thành Thái. He was fast to realize that his power was very limited, that the Patenôtre treaty was never respected and that he had no right with regard to the management and future of his country. Contrary to his predecessor Ðồng Khánh, close to the colonial authorities, he took a passive resistance by trying to thwart their policies in a systematic manner with his provoking remarks and amicable gestures. His fist virulent altercation with the Resident General Alexis Auvergne was noticed at the inaugural ceremony of the new bridge spanning across the Perfume river. Proud of technical prowess and confident of the sturdiness of the bridge, Alexis Auvergne did not hesitate to tell Thành Thái with his habitual cynicism:

When you would have seen this bridge collapse, your country would be independent.

To show the importance that the colonial authorities has given to the new bridge, they named it « Thành Thái ». This made the emperor mad. Using as a pretext that everyone can walk over his head when crossing the bridge, he forbade his subjects to call the bridge by its new name and incited them to use the old name « Tràng Tiền ».

Some years later, the bridge collapsed during a violent storm. Thành Thái was fast to recall Alexis Auvergne of what he had said with his black humor. Alexis Auvergne was red with shame and had to clear off at these embarrassing remarks. The dissension with the authorities grew day by day until the replacement of the old Resident General by Sylvain Levecque. The latter was fast to place a network of strict surveillance when he learned that Thanh Thai continued to approach his people through the bias of his reforms and his disguise in plain clothes or as a beggar in villages. He was the first emperor of Vietnam to take the initiative of having his hair cut the European fashion, which astonished so many of his mandarins and subjects when he first appeared. But he also was the first emperor to encourage his subjects to follow French education. He was the artisan of several architectural projects. He was also the first emperor of the Nguyen dynasty who wanted to pay enormous attention to the daily life of his subjects and to know their daily difficulties. It was reported that during an escorted excursion, he met on his way a poor man who was hauling a heavy load of bamboo. He body guard wanted to ease the way but he stopped him by saying:

I am neither citizen nor emperor as I should be in this country. Why do you chase him away?

During his excursions, he often used to sit on a mat, surrounded by the villagers and to discuss all the issues with them. It was in one of his excursion that he brought back to the purple city an oarswoman who accepted to marry him and became his concubine. He was well known as an excellent drummer.

That is why he summoned all the best drummers in the country to the purple city, asked them to play drums before his court and reward them generously according to their merit. It was reported that one day, he met a drummer who used to tilt his head when playing. Wanting to help him correct this funny habit, he told him jokingly:

If you keep on playing that way, I will have to have your head rolled.

From then on, the drummer, worrying incessantly about the next call, was overwhelmed by fear and died of a heart attack. One day, knowing the death of the drummer, Thanh Thai was taken my remorse, summoned his family and gave them a large sum of money to take care of their daily needs.

His way of joking, his frequent disguises, his sometimes strange behavior incomprehensible to the colonial authorities gave them an opportunity to brand him a lunatic.

As for Thành Thái, he was deported first to Vũng Tàu (former Cap St. Jacques) in the Fall of 1907, then later to the Reunion Island with his son, emperor Duy Tân in 1916. He was only allowed to return to Vietnam in 1945 after the death of Duy Tân and to stay confined within Vũng Tàu, South Vietnam during the last years of his life.

Is it possible to brand him lunatic when it is known through his poem titled « Hoài Cổ » ( Remember the Past ) that Thành Thái was so lucid and never stopped to groan with the pain facing the alarming situation of his country? Other eight seven-foot verses we know such as The storm of the year of the Dragon in 1904 ( Vịnh Trần Bão Năm Thìn ) or Profession of Faith ( Cảm Hoài ) not only show Thành Thai’s perfect mastery in the strict application of the difficult rules in Vietnamese poetry but also the painful pride of a great emperor who, in spite of a forced exile for almost half a century ( 1907-1954 ) by the colonial authorities, continued to display his conviction and unshakable faith in the liberation of his country. Through him it is already seen forging on this land of legends the instruments of a future revolt.

For him, his incurable illness was the goal to realize his intention, to give his people the dignity so long waited and to show future generations the sacrifice and the price which even he, a person considered alienated by the colonial authorities, had to pay for that country ( 47 years of exile ). In the political context of the time, he should not reveal himself of this « illness ».

Up to now, no historic document show us Thành Thái’s insanity but rather it reveals a great emperor’s lunacy of the love of his country and people, neverending affliction of a great patriot facing the destiny of his country.