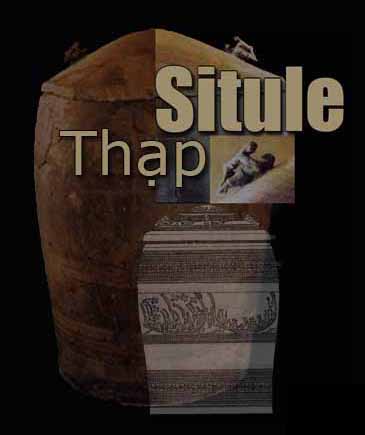

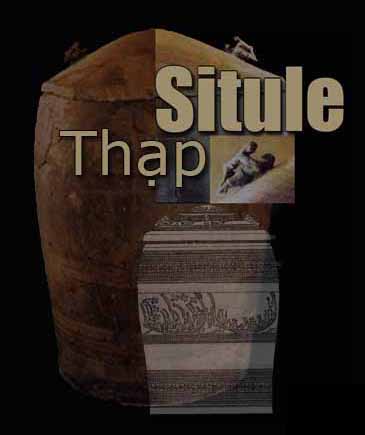

Thạp đồng Đào Thịnh

Mặc dầu thạp và trống đồng được xem như hình với bóng nhưng thạp rất ít được phổ biến trong dân gian vì có nhiều lý do. Trước hết ít có sách vở ghi chép về thạp đồng. Vã lại địa vực phân bố cũng rất giới hạn. Trống đồng thường được trông thấy khắp nơi ở Đông Nam Á và phía nam của Trung Hoa thì ngược lại những thạp đồng chỉ tìm thấy phần lớn ở Việtnam. Thạp thường tập trung ở các lưu vực các sông lớn như sông Hồng, sông Mã và sông Cả mà theo truyền thuyết dân Việt đấy là lảnh thổ của nhà nước Văn Lang dưới thời các vua Hùng. Ở Trung Hoa, chỉ có một số ít ỏi thạp đồng tìm thấy ở các tỉnh biên thùy như Quảng Tây, Vân Nam, Quảng Đông và mang tính chất trao đổi và thương mại. Cũng có một thạp đồng mà được tìm thấy ngoài lệ ở Phong Điền (Thừa Thiên Huế) cùng lúc với một trống đồng Heger loại I , một hiện vật có lẽ được trao đổi với cư dân văn hóa cùng thời Sa Huỳnh.

Văn hóa Đồng Sơn

Nhưng đó cũng là một thạp đồng duy nhất được khám phá ở vùng Thừa Thiên Huế cho đến năm 2005. Hơn một thế kỷ đi qua, từ khi khám phá được một cái nắp đầu tiên của thạp đồng nằm úp trong trống đồng Ngọc Lũ (1893-1894) cho đến ngày nay, thì trên 250 thạp đồng được biết và kiểm kê thì chỉ có 15 thạp đồng được tìm thấy ở Trung Hoa (9 thạp trong ngôi mộ của Nam Việt Vương Triệu Muội, vua thứ hai của nước Nam Việt, cháu nội Triệu Đà, 1 thạp trong một ngôi mộ ở Quảng Đông, 4 thạp trong mộ La Bạc Loan ( Quảng Tây ) và một thạp đồng trong khu vực Tianzimiao (Điền Quốc, Vân Nam). 235 thạp đồng còn lại thì rải rác ở các địa điểm khai quật của văn hóa Đồng Sơn thường thấy ở Việtnam và phân bố ra hai loại: 205 thạp không có nắp và 30 thạp có nắp. Chỉ đến năm 1930 thạp đồng được một học giả người Nhật Bản Umeshra Sueji miêu tả lần đầu tiên một cách sơ lược. Sau đó, năm 1936, thạp đựợc giới thiệu bởi nhà khảo cổ Olov Jansé, một cộng tác viên tạm thời của trường Viễn Đông Bác Cổ Pháp sau cuộc khai quật di tích Đồng Sơn.

Các thạp đồng thường thuộc về dòng dõi qúi tộc. Đó là sự nhận xét mà các nhà khảo cổ hay có sau các cuộc khai quật ở các mộ táng của giới quí tộc và các nhà lãnh tụ địa phương. Thạp đồng không phải là một biểu hiệu quyền lực như trống đồng mà nó là một sản phẩm có tính chất đa năng. Nó được sử dụng

- để chứa các loại chất lỏng (nước cúng , rượu thờ cúng hay dầu thực vật)

- làm đồ đựng và tích trử lương thực ( cá , cua, tôm, thịt thú rừng vân vân …) để phòng ngừa nạn đói kém,

- để chứa vỏ trấu ( thạp Làng Vạc (Nghệ Tịnh))

- làm một chiếc quan tài tùy táng mà tìm thấy được năm 1995 một tử thi trẻ em được cuốn bằng chiếu cói qua thạp Hợp Minh (Yên Bái) hay đựng nguyên một chiếc sọ của người quá cố hay của nạn nhân trong việc tế thần qua thạp Thiệu Dương (Thanh Hóa) khám phá năm 1961

- làm vật dụng đựng thang tro và xương cốt sau khi hỏa táng với ( thạp Đào Thịnh (Yên Bái) năm 1960

- làm một hiện vật dùng trong lễ tang để đưa người quá cố về thế giới bên kia với thạp Vạn Thắng (Phú Thọ) phát hiện năm 1962.

Con thú đang tha mồi được thấy

trên nắp thạp Vạn Thắng. Hànội 2008

Thông thường, thạp mà được thấy ở Việtnam trong các mộ táng sang trọng thường có tính cách nghi lễ đối với dân tộc Lạc Việt ( hay người Đồng Sơn). Đối với các người nầy , thạp được xem không những là một vật dụng rất cần thiết trong cuộc sống hằng ngày mà nó còn là một vật mà người quá cố không thể thiếu khi về thế giới bên kia. Từ một vật dụng hằng ngày cho đến khi trở thành một đồ tùy táng đó là một việc rất thông thường đối với người Đồng Sơn vì đây là một khái niệm chia sẻ giữa người quá cố và những người thân thuộc, một truyền thống đuợc trường tồn dưới nhiều hình thức từ thời xa xưa trong các nền văn minh cổ đại nhất là trong nền văn hóa Đồng Sơn.

Thạp có hình khối trụ thuôn dần từ miệng xuống đáy và có thể có vành gờ miệng để dễ đậy nắp đồng hình vòm. Thạp thường có hai quai hình chữ U lộn ngược. Thạp không có phong phú như trống đồng bởi vì nó mang tính cách thông dụng. Trên thân của thạp có các băng phù điêu hoa văn trang trí với những mô típ mà được thường thấy trên trống đồng (vòng tròn có tiếp tuyến, những đường gẫy khúc đan vào nhau tạo hình thoi, vạch ngắn thẳng vân vân…) hay là hoa văn rất đơn giản.

Nhưng đôi khi cũng có những thạp đồng mang vẻ đẹp vô song và trang trí rất tinh vi cũng không thua chi trống đồng. Đấy là trường hợp của các thạp Đào Thịnh (Yên Bái), Vạn Thắng ( Phú Thọ), Hợp Minh (Yên Bái ), mỗi thạp đều có nắp hình vòm, được trang trí ở ngay giữa trung tâm một ngô i sao nhiều cánh hay ở chung quanh có gắn 4 khối tượng người hay thú mà được bố trí đi ngược chiều kim đồng hồ.Trên thạp Đào Thịnh thì tìm thấy có 4 khối tượng, mỗi khối là một đôi nam nữ đang ở tư thế giao hợp còn trên nắp Vạn Thắng (Phú Thọ) thì có bốn con thú đang săn mồi hay là 4 con bồ nông trên nắp Hợp Minh (Yên Bái).

Khi quan sát và so sánh các hoa văn trang trí thuyền bè với những người hóa trang, đầu đội mũ lông chim trên thân của thạp Đào Thịnh với các hình chạm khắc trên các trống đồng Heger loại I (Ngọc Lũ, Hoàng Hạ, Cổ Loa, Sông Đà (Moulié) …) thì có cảm tưởng đây là những sản phẩm có cùng một phong cách nghệ thuật và được chạm khắc bởi những nghệ nhân khéo léo được đạo tạo từ một trường, xuất thân từ một nền văn hóa chung . Như vậy chứng tỏ những sản phẩm nầy thể hiện cùng có một chủ nhân sáng tạo chung, đó là cư dân của nền văn hóa Đồng Sơn đã có hai thiên niên kỷ trước đây. Rất khó phân loại các thạp đồng nếu dựa vào yếu tố hoa văn bởi vì các thạp đồng được tìm thấy hầu hết đều có hoa văn mang tính cách biểu tượng.

Có những nhà khảo cổ gợi ý dựa kích thước làm tiêu chuẩn trong việc phân loại các thạp nhưng vì gam thạp quá đa dạng từ to (các thạp Hợp Minh, Thiệu Dương, Xuân Lập vân vân…) đến bé như minh khí đựợc tìm thấy ở các mộ táng Châu Can (Hà Nam), Núi Nấp ( Thanh Hoá ) khiến khó dùng tiêu chí nầy được. Cuối cùng chỉ có khái niệm dùng nắp thạp là có căn bản hợp lý nhất trong việc phân biệt các thạp đồng. Dựa trên mỹ thuật trang trí văn hoa thì phải nói có sự phong phú rỏ ràng ở nơi các thạp có nắp. Và cũng nhờ có gờ miệng thì mớ i có thể biết được thạp đó có nắp hay không dù nắp thạp có thể mất hay không còn nửa.

Với các trống đồng, thạp không những là một phần tử tiêu biểu của nên văn hóa Đồng Sơn mà còn là bằng chứng cốt lõi có nguồn gốc ở địa phương. (Việtnam)

Đôi khi nhìn thạp làm ta nhớ đến chiếc gùi bằng mây mà thường được thấy hiện nay ở các dân tộc thiểu số ở Việtnam. Gùi cũng có các quai dùng để buộc dây xách thuận tiện cho việc di chuyển. Theo các nhà khảo cổ học , chiếc thạp là hình ảnh của chiếc gùi mà cư dân Đồng Sơn thường dùng thưở xưa với nắp để đậy khi dùng để chứa đồ. Theo sự quan sát của nhà khảo cổ học Việtnam Nguyễn Việt, những chiếc thạp nhất là chiếc được trưng bày ở bảo tàng viện Barbier-Mueller ở Genève (Thụy Sĩ) rất có thể tiếp nhận ảnh hưởng của các nghệ nhân khéo léo của vương quốc Điền ở Vân Nam. Có thể nói vào thời đó, văn hóa Đồng Sơn đuợc phát triển trong bối cảnh cởi mở, đã trao đổi lẫn nhau những thông tin và sản phẩm với Điền quốc qua sông Hồng. Lấy nguổn nước ở Vân Nam, sông Hồng được xem thời đó như là đường tơ lụa sông. Dù sao đi nửa, cũng có thể khẳng định một cách quả quyết là thạp đồng không phải là một sản phẩm của Trung Hoa mà nó mang nhiều tính chất địa phương (Việtnam).

Référence bibliographique:

Thạp Đồng Đông Sơn Hà Văn Phùng Nhà Xuất Bản Khoa Học Xã

Những dấu vét đầu tiên của thời đại đồ đồng thau ở Việtnam, NXb Khoa học xã hội, Hànội,1963. Lê văn Lan, Phạm văn Kỉnh, Nguyễn Linh