En raison de l’abondance des trouvailles archéologiques en étain à Óc Eo dans le delta du Mékong (An Giang), l’archéologue français Louis Malleret n’hésite pas à emprunter le nom Óc Eo pour désigner cette civilisation de l’étain. On commence à avoir désormais une vive lumière sur le royaume du Founan ainsi que sur ses relations extérieures lors de la reprise des campagnes de fouilles menées tant par des équipes vietnamiennes( Đào Linh Côn, Võ Sĩ Khải , Lê Xuân Diêm) que par l’équipe franco-vietnamienne dirigée par Pierre-Yves Manguin entre 1998 et 2002 dans les provinces An Giang, Đồng Tháp et Long An où se trouve un grand nombre de sites de culture Óc Eo. On sait que Óc Eo était un grand port de ce royaume et une plaque tournante dans les échanges commerciaux entre la péninsule malaisienne et l’Inde d’un côté et le Mékong et la Chine de l’autre. Comme les bateaux de la région pouvaient couvrir de longues distances et devaient suivre la côte, Óc Eo devint ainsi un passage obligatoire et une étape stratégique importante durant les 7 siècles de floraison et de prospérité du royaume du Founan.

Bảo tàng lịch sử Hà Nội

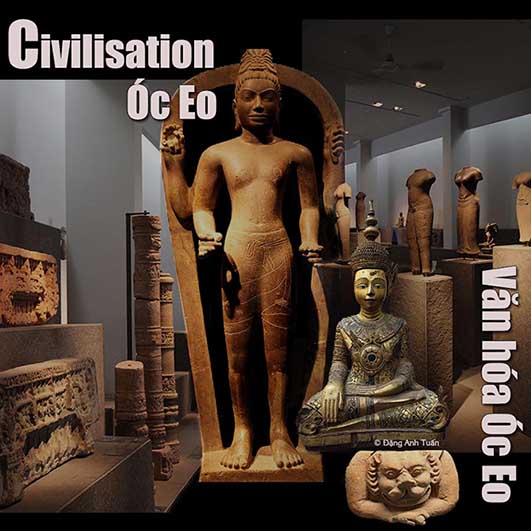

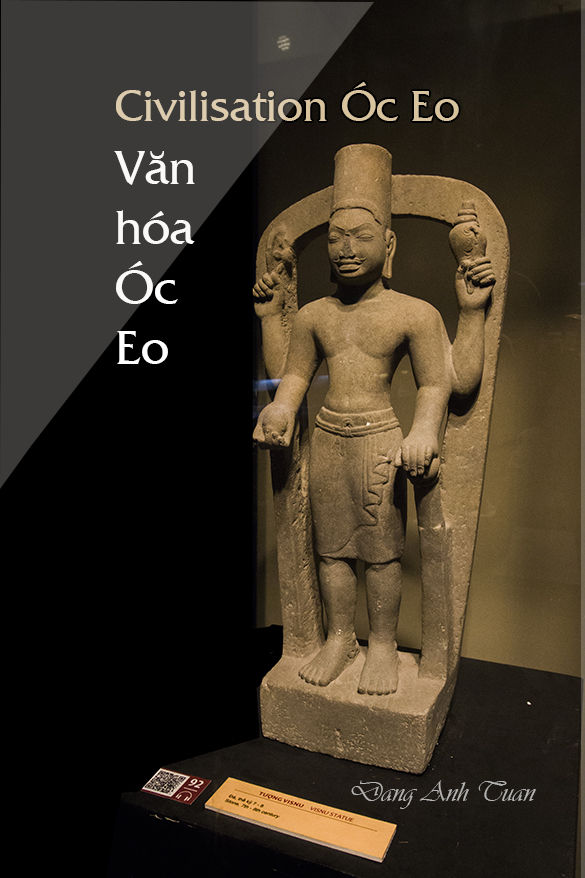

Cette civilisation de l’étain se distingue non seulement par sa culture du riz flottant mais aussi par son commerce avec l’extérieur. On a découvert un grand nombre d’objets autres que ceux de l’Inde trouvés sur les rives du Founan: fragments de miroirs en bronze datant de l’époque des Han antérieurs, statuettes bouddhiques en bronze attribuées aux Wei, un groupe d’objets purement romains, des statuettes de style hellénistique en particulier une représentation de Poséidon en bronze. Ces objets étaient échangés probablement contre des marchandises car les Founanais ne connaissaient que le troc. Pour l’achat des produits de valeur, ils se servaient des lingots d’or et d’argent, des perles et des parfums. Ils étaient connus comme d’excellents bijoutiers. L’or était finement travaillé avec de nombreux symboles brahmaniques (Vishnu, Nandin, Vahara, Garuda, Shesha, Kurma etc…). Les bijoux (boucles d’oreilles en or au fermoir délicat, filigranes d’or admirables, perles de verre, intailles etc… ) exposés dans les musées de Đồng Tháp, Long An et An Giang témoignent non seulement de leur savoir-faire et de leur talent mais aussi de l’admiration des Chinois dans leurs récits durant leur contact avec les Founanais.

Galerie des photos

Bảo tàng lịch sử Saigon

Văn Hóa Óc Eo

Au Musée national de l’histoire (Saïgon)

Vì lý do tìm ra được nhiều các di vật cổ bằng thiếc ở Óc Eo vùng châu thổ sông Cửu Long (An Giang), nhà khảo cổ học Pháp Louis Malleret không ngần ngại mượn tên Óc Eo để chỉ định nền « văn hóa đồ thiếc ». Chúng ta mới bất đầu từ đó có cái nhìn sáng tỏ về vương quốc Phù Nam và các mối quan hệ bên ngoài trong các chiến dịch khai quật kế tiếp lại sau nầy với sự điều khiển của nhóm người Việt (Đào Linh Côn, Võ Sĩ Khải, Lê Xuân Diêm) và nhóm người Việt Pháp do ông Pierre-Yves Manguin đảm nhận giữa năm 1998 và 2002 ở An Giang, Đồng Tháp và Long An, các nơi mà có nhiều hiện vật của nền văn hóa Óc Eo. Chúng ta biết rằng Óc Eo là một thương cảng trọng đại và trung tâm vận chuyển trong việc trao đổi hàng hóa giữa một bên bán đão Mã Lai và Ấn Độ và bên kia Trung Hoa và đồng bằng sông Cửu Long.

Thông thường các thuyền bè trong vùng cần đi xa và phải dọc theo bờ biển, Óc Eo trở thành vì thế một địa điểm phải đến và chặn đường chiến lược quan trọng suốt 7 thế kỷ phồn thịnh cho vương quốc Phù Nam. Nền văn hóa Óc Eo được xem nổi bật không những trong việc trồng lúa nước mà còn luôn cả quan hệ buôn bán với các nước ngoài khu vực. Chúng ta khám phá được một số di vật khác hẳn với những đồ vật có nguồn gốc văn hóa Ấn Độ ở các lưu vực sông của vương quốc Phù Nam: những mảnh gương đồng có từ thời Tây Hán, các tượng đồng thì đời nhà Tùy, hạt chuổi La Mã, một số đồ vật thời kỳ Hy Lạp hóa nhất là có một biểu tượng Poseidon bằng đồng. Các hiện vật nầy chắc chắn có được nhờ sự trao đổi hàng hóa vì người dân Phù Nam chỉ biết giao dịch trao đổi. Để mua các sản phẩm có giá trị, họ thường dùng thỏi vàng hay bạc, các hạt chuổi và nước hoa. Họ có tiếng là những thợ kim hoàn xuất sắc. Các hiện vật bằng vàng được làm một cách tinh xão với các biểu tượng của đạo Bà La môn (hình thần Vishnu, bò thần Nandin, lợn thần Vahara, chim thần Garuda, rắn thần Shesha, rùa thần Kurma…). Các trang sức (như khuyên tai bằng vàng hay có cái móc tinh vi, dây chuyền vàng tuyệt vời, hạt cườm, đá màu etc…) thường thấy trưng bày ở các bảo tàng viện An Giang, Đồng Tháp hay Long An nói lên không những sự khéo léo của người Óc Eo trong nghề làm kim hoàn mà luôn cả sự ngưỡng mộ cũa người Trung Hoa qua các câu chuyện kể lại trong thời gian giao thương với người dân Óc Eo.

Because of the abundance of tin archaeological finds at Óc Eo in the Mekong delta (An Giang), French archaeologist Louis Malleret does not hesitate to borrow the name Óc Eo for designating this tin civilization. We begin to have now a deep light on this kingdom as well as its external relations during the resumption of excavations undertaken both by Vietnamese teams (Đào Linh Côn, Võ Sĩ Khải, Lê Xuân Diêm) and French-Vietnamese team led by Pierre-Yves Manguin between 1998 and 2002 in An Giang, Ðồng Tháp and Long An provinces where a large number of sites of Óc Eo culture are located. We know Óc Eo was a major port of this kingdom and a transit hub in trade exhanges between Malaysian peninsula and India on one hand and the Mekong and China on other one. As the boats of the region could cover long distances and had to follow the coast, Óc Eo thus became a mandatory stop and a important strategic step during the 7 centuries of blooming and prosperity for Funan kingdom.

This tin civilization is distinguished not only by the floating rice cultivation but also its external trade. We have discovered a large number of objects other than that of India found on Funan shores: fragments of bronze mirrors dating from the Han anterior period, Buddhist bronze statuettes attributed to Wei dynasty, a group of purely Roman objects, statuettes of Hellenistic style in particular a Poseidon bronze representation. These objects were probably exchanged for goods because Funan people only knew the barter. For the purchase of valuable products, they used golden and silver ingots, pearls and perfumes. They were known as excellent jewelers. The gold was finely worked with numerous Brahmanic symbols. The jewels (golden earrings with the delicate clasp, admirable golden filigrees, glass pearls, intaglios etc.) exposed in the museums of Đồng Tháp, Long An and An Giang testifies not only of their know-how and their talent but also the the Chinese’s admiration in their narratives during their contact with Funan people.