I would like to give to this great Vietnamese politician a great homage by slightly modifying the two verses he composed in his poem « Improvisation » translated into French by Nguyễn Khắc Viện in Anthology of the Vietnamese Literature:

A thousand Autumns have passed, water keeps its face

A thousand generations have watched the moon similar to itself;

by my two following verses:

A thousand Autumns have passed, Vietnam keeps its independence

A thousand generations have venerated Nguyễn Trãi similar to himself.

© Đặng Anh Tuấn

One can sum up the life of this great politician by means of verse 3248 of the Vietnamese literature great classical of Nguyễn Du in 18th century:

Chữ Tài liền với chữ Tai một vần

The word Tài (Talent) rhymes perfectly with the word Tai ( Misfortune ).

to evoke not only his incredible talent but also his tragic end regretted by so many Vietnamese generations. Facing the brutal force that represented emperor Chenzu of the Ming ( Minh Thánh Tổ ) under the command of Tchang Fou ( Trương Phụ ) during his invasion of Đại Việt ( ancient name of Vietnam) in the ninth month of the year Binh Tuất (1406), Nguyễn Trãi knew how to give what Lao Tseu had said in the Book of Life and Virtue:

Nothing is more supple and soft in the world than water

However to attack what is hard and strong

Nothing surpass it and nobody can match it.

That the weak surpasses the strong

That the supple surpasses the hard

Everyone knows.

But nobody put this knowledge into practice

a tremendous conceptualization and elaborated an ingenious strategy allowing the Vietnamese, weak in number to come out victorious during that confrontation and regain their national independence after 10 years of struggle. With the landowner Lê Lợi, known later as Lê Thái Tổ and 16 comrades-in-arms tied by a pledge at Lung Nhai (1406 ), and 2000 peasants at mount Lam Sơn in the mountainous region West of Thanh Hoá, Nguyễn Trãi arrived at turning the insurrection into a war of liberation and converting a band of ill-armed peasants into a people’s army of 200,000 men strong a few years later.

The strategy known as « guerilla » was shown very effective because Nguyen Trai was successful in putting into practice the doctrine advocated by the Chinese Clausewitz, Sun Zi (Tôn Tữ) in the Spring and Autumn ( Xuân Thu ) era, based on the following variables: Virtue, Time, Land , Leadership, and Discipline in the conduct of the war. Nguyễn Trãi had an opportunity to say he preferred winning the heart of the people to citadels . When there is harmony between the leaders and the people, the latter will accept to fight until their last breath. The cause will be heard and won because Heaven takes side with the people, which Confucius had the opportunity to recall in his Canonical Books:

Thiên căng vụ dân, dân chi sở dục, thiên tất tòng chí

Trời thương dân, dân muốn điều gì Trời cũng theo

Heaven loves people so much it grants what people ask for.

One can say that with Nguyễn Trai, the humanist inclination of Confucian doctrine has taken its full development. To make sure of the support and adhesion of the people in his war for independence, he did not hesitate to take advantage of his people’s superstition and credulity. He asked his close relations to climb up trees and use toothpicks and honey to carve the following sentence on the leaves.

Lê Lợi vì dân, Nguyễn Trãi vì thân

Lê Lợi for the people, Nguyễn Trãi for Lê Lợi

This attracted ants to eat the honey leaving the message marked on the leaves which were blown off by the wind into streams and other bodies of water. When people picked up the leaves as such, they believed that the message came from the will of Heaven and massively joined he war of liberation.

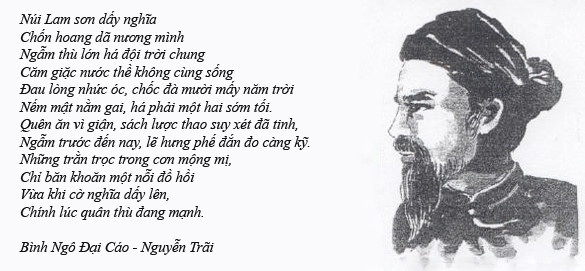

Humanist by conviction, he always thought not only of the sufferings of his people but also that of his enemies. He had the opportunity to emphasize in his letter to Chinese General Wang Toung ( Vương Thông ) that the duty of a commander is to dare make a decision, undo hatred, save human lives and cover the world with good deeds in order to bequeath a great name to posterity ( Quân Trung Từ Mệnh Tập ). He let defeated Chinese generals Wang Toung ( Vương Thông ), Mã Anh, Fang Chen ( Phương Chính ) go back to their country with 13000 captured soldiers, 500 junks and thousands of horses. Concerned about peace and the happiness of his people, in his masterpiece « Proclamation of the Ngô Pacification » ( Bình Ngô Ðại Cáo ) that he wrote after winning the war and driving the Chinese army out of Vietnam, he recalled that it was the time to act with wisdom for the safety of the people.

To make China not to feel humiliated by the bitter defeat and to restore above all a long lasting peace and happiness for his people, he proposed China a vassal pact with a tribute of two real-sized statues in fine metal every three years ( Ðại thần kim nhân ) in compensation for the two Chinese generals Liou Cheng ( Liễu Thăng ) and Leang Minh ( Lương Minh ) who died in combat.

In the first years of the struggle, Nguyễn Trãi knew biting and bleeding defeats many times (the death of Lê Lai, Ðinh Lễ etc… ), which forced him to take refuge at Chi Linh three times with Lê Lợi and his partisans. Despite of that, he never felt discouraged because he knew that the people fully supported him. He often compare the people with the ocean. Nguyễn Trãi had the opportunity to tell his close relations:

Dân như nước có thể chở mà có thể lật thuyền.

The people is like water which can move and sink the ship.

The remark made by his father Nguyễn Phi Khanh, captured and brought to China with other educated Vietnamese including Nguyễn An, the future builder of the forbidden Citadel in Peking, during their separation moment at the Sino-Vietnamese border, continued to be vivid in his mind and made him ever more determined in his unwavering conviction for the his just cause:

Hữu qui phục Quốc thù, khóc hà vi dã

Hãy trở về mà trả thù cho nước, khóc lóc làm gì

You’d better go back and avenge the country, it doesn’t help crying.

He spent whole nights in search of a strategy permitting to counter the Chinese army at the zenith of its force and terror. Being updated on the dissensions within the ranks of its adversaries, the difficulty that emperor Xuanzong of the Ming was having at the northern border with the Hungs after the disappearance of Chengzu in 1424 and the damages that the Chinese army suffered during the last military engagements in spite of their territorial success, Nguyễn Trãi did not hesitate to propose a truce to general Ma Ki. The truce was voluntarily accepted by both sides because each side thought they could take advantage of this respite either to consolidate their army in waiting for reinforcements from Kouang Si and Yunnan and a larger scale military engagement ( for the Ming ), or to rebuild an army already suffering important losses of lives and to change the strategy in the struggle for liberation ( for the Viet ).

Taking advantage of the unfamiliarity of the terrain by the Chinese reinforcing army coming from China, he was fast in his maneuvering putting into work the » the full and the void » doctrine advocated by Sun Zi who had said in his work « The Art of War »:

The arm must be similar to water

Since water avoids heights and falls into hollows,

The army avoids the full and attacks the void.

which permitted him to decapitate Liou Cheng and his army in the « void » of Chi Lăng defined by Sun Zi, in the mountainous and quagmire narrow pass near Lang Son. He did not give any respite to Liou Cheng’s successor, Leang Minh to regroup the remainder of his Chinese army by setting a trap around the city of Cần Trạm. Then he took advantage of the success to rout the reinforcing army of the Chinese general ( Mộc Thanh ), which force the latter to drive off and go back alone to Yunnan ( Vân Nam )

Fearing to lose the bulk of his troops in a confrontation and worrying about saving the blood of his people, he chose to implement the policy of isolating big cities such as Nghệ An, Tây Ðô, Đồng Quan ( ancient name of the capital Hànội ) by investing all forts and small cities surrounding them, by incessantly harassing the supply troops and by neutralizing all reinforcing Chinese troops. In order to prevent the eventual return of the invaders and to disorganize their administrative structure, he placed in the liberated cities a new administration led by young and educated recruits. He did not stop sending emissaries to Chinese or Vietnamese governors of these towns to convince them to surrender under penalty of being brought to justice and sentenced to death in case of resistance. This turned out to be fruitful and rewarding because it compelled generalissimo Wang Toung and his lieutenants to surrender unconditionally as he was aware that it was impossible to hang on to Ðồng Quang any longer without reinforcement and supply. It was not only a war of liberation but also a war of nerves that Nguyen Trai has successfully conducted against the Ming.

Independence regained, he was appointed Minister of the Interior and member of the Secret Council. Known for his righteousness, he was fast to become the privileged target of the courtesans of king Lê Thái Tổ who began to take offense at his prestige. Feeling the risk of having the same fate reserved for his comrade in arms Trần Nguyên Hản and imitating the Chinese senior advisor Zhang Liang ( Trương Lương or Trương Tử Phòng ) of Han Emperor Liu Bang ( Lưu Bang or Hán Cao Tổ ), he requested king Lê Lợi to allow him to retire to mount Côn Sơn, a place he had spent his whole youth with his grand father Trần Nguyên Ðán, a former great minister regent of the Tran king, Trần Phế Ðế and the great grand son of general Trần Quang Khải, one of the Vietnamese heroes in the struggle against the Mongols of Kubilai Khan.

It was here that he wrote a series of composed writings that recalled not only his profound attachment to nature which he made a confidant of, but also his ardent desire to give up honors and glory and to regain serenity. It was also through his poems that one finds in him a profound humanism, an extraordinary simplicity, an exemplary wisdom and an inclination to retreat and solitude. There, he has insisted that a man’s life lasted only one hundred years at the most. Sooner or later one will return to sand and dust. What counts in a man is his dignity and honor such as a blue blanket ( symbol of dignity ) that had been defended energetically by the learned Chinese Vương Hiền Chi of the Tsin dynasty during the intrusion of a burglar to his home, in his poem » Improvisation on a Summer day » ( Hạ Nhật Mạn Thành ) or his freedom such as that of the two Chinese hermits Sào Phú and Hua Dzo of the Antiquity in his poem » The Côn Sơn Song » ( Côn Sơn Ca ).

In spite of his early retirement, he was accused of killing the king a few years later and was tortured in 1442 with all his family members because of the death of he young king Lê Thái Tông, in love with his young concubine Nguyễn Thị Lộ and accompanied by her to the lichee garden. One knows everything except the human heart that stays unfathomable, that was what he said in his poem « Improvisation » ( Mạn Thuật ) but that was what happened to him in spite of his foresight. His memory was restored only a few dozen years later by the great king Lê Thánh Tôn. One can keep in this scholar not only the love he always carried for his people and his country but also the respect he always knew how to keep toward his adversaries and nature. To this talented learned Vietnamese, his memory should be honored by quoting the phrase that Yveline Féray wrote in the foreword of her novel « Ten thousand Springs« :

The tragedy of Nguyễn Trãi is that of a so great man living in a too little society