Version française

Version vietnamienne

Galerie des photos

At a time when the kingdom of Funan was weakening, a vassal principality of this kingdom, which Chinese historians often referred to as Chenla (Chân Lạp) in their annals, attempted to forge its destiny in the middle Mekong basin near the archaeological site of Vat Phu in the Champassak province (present-day Laos). This is the only name we have to this day. No Sanskrit or Khmer word corresponds to the ancient sound Tsien lap. The existence of this kingdom dates back to the end of the 6th century. Similar to the kings of Funan, those of Chenla also have a dynastic legend: a solar-origin Brahmin priest named Kambu Svayambhuva received from the god Shiva himself a nymph of lunar origin in marriage, the beautiful Mera.

From this union of K(ambu) and Merâ, a line of sovereigns was born, that is, the descendants of Kambujadesha, meaning « land of the descendants of Kambu, » intended to explain the name of the Khmers. This word Kambujadesha, abbreviated as Kambuja, was first discovered in 817 in an inscription of Po Nagar in Champa (or present-day Nha Trang, Vietnam).

During the French colonial period, this name Kambuja was Francized as « Cambodge. » As for the word Chenla, it appeared in the history of the Sui (589-619), where the sending of an embassy from this country was mentioned in 616-617. Located southwest of Lin Yi (future Champa) and a vassal state of Funan, the kingdom of Chenla (Chân Lạp) (future Cambodia), having become powerful, did not hesitate to seize the latter and subjugate it. This fact was reported not only in the New History of the Tang (618-907) by the Chinese historian Ouyang Xiu but also in an unpublished inscription from Sambor-Prei Kuk, which praised the king of Chenla, Içanavarman I, son of King Mahendravarman, for having expanded his parents’ territory with his grand exploits. This monarch established his capital at Sambor-Prei Kuk, renamed Ishanapura.

The fragmentation of Chenla into small states was witnessed again. It was only in 654 that Jayavarman I, a great-grandson of Içanavarman I, succeeded in reunifying his ancestor’s country and established his capital near Angkor. Upon his death, Chenla again broke up into numerous principalities, and soon the principality of Shambupura (today Sambor on the Mekong) managed to impose its authority. Its king, Jayavarman II, settled in Rolûos and proclaimed himself king of the entire Kambuja in 802. Then the settlement and religious sites of the Óc Eo plain began to be abandoned as the center of gravity of the new political formation from the North moved away from the coast to gradually approach the site of the future capital of the Khmer empire, Angkor.

According to researcher J. Népote, the Khmers coming from the North through Laos appear like Germanic tribes in relation to the Roman Empire, attempting to establish a unified kingdom inland known as Chenla. They saw no interest in maintaining the technique of floating rice cultivation because they lived far from the coast. They tried to combine their own mastery of water retention with the contributions of Indian hydraulic science (the baray) to develop, through multiple trials, an irrigation system better adapted to the ecology of the hinterland and to the local varieties of irrigated rice.

It is reported that in Chinese annals, Chenla was divided into a « Land Chenla » and a « Water Chenla » at the beginning of the 8th century. The former was established in the old territories of Chenla, expanded according to its military successes, from the Dangrek range to the middle Mekong valley and westward to Burinam, now part of the Thai province of Korat, while the latter corresponded to a multitude of fiefs of former Funan and was subject to the royal authority of the island of Java (Indonesia). Then, through a stele of Sdok Kak Thom dating from 1052 and found 25 km from Sisophon, we learn that Jayavarman II was crowned king in 802 after freeing his country from the tutelage of Java, and his country regained its unity under the name Chenla.

The latter soon gave way to the birth of the Angkorian empire at the beginning of the 9th century. It first experienced its peak and glory with King Suryavarman II, whom historians have often compared to the Sun King Louis XIV of France. Of a warlike temperament, he did not hesitate to first ally with the Chams to attack the kingdom of Đại Việt under the reign of King Lý Thần Tôn in 1128, but he was repelled in the Nghệ An region. He then tried to maintain his grip on Champa by placing his brother-in-law Harideva as ruler over the capital Vijaya (present-day Bình Định in Vietnam).

But this attempt ended in a crushing failure against one of the greatest Cham kings, Jaya Harivarman I, who recaptured Vijaya in 1149. Yet Chinese chroniclers spoke of him with great deference. Beyond the frenzy of his territorial conquests, Suryavarman II had a large number of splendid monuments built, among which was the famous site of Angkor Wat. According to the Italian researcher Maria Albanese from the I.I.A.O institute, it seems possible that Suryavarman II died following a disastrous military expedition into Vietnamese territory in 1150.

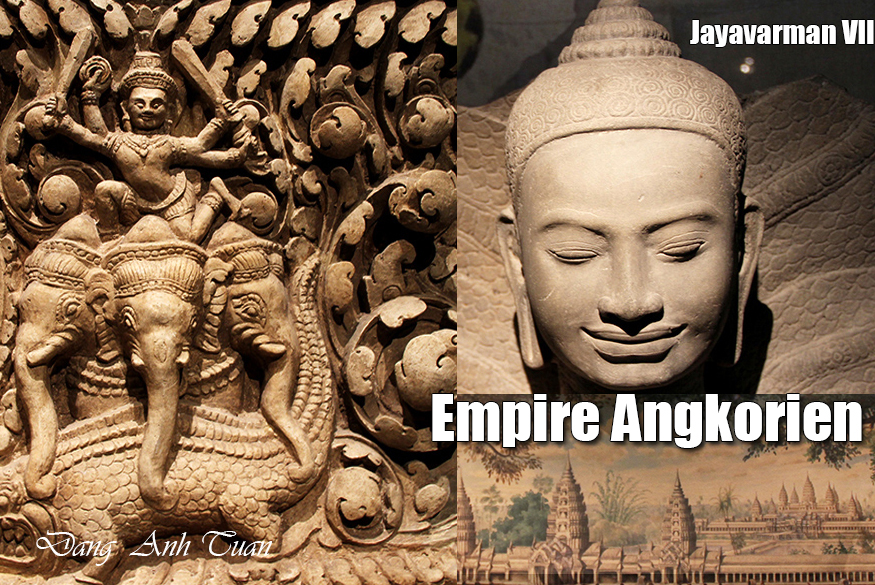

Then the empire of the Khmer kings expanded under Jayavarman VII, one of the fascinating personalities in universal history. During his reign, he managed to push back the limits of his empire by annexing Champa, Lower Burma, Thailand, and Laos. Georges Coedès, former director of the French School of the Far East (EFEO), painted for us a striking portrait of this great king, that of a pharaoh who can boast of having moved so much stone (Angkor Thom, Ta-Prohm, Bantay-Kdei, etc.).

Map of the empire

But after his death, due to the gigantic enterprises and incessant wars against his neighbors (Chams, Vietnamese, and Thais), the Angkorian empire began to experience a rapid decline caused by the multiple capture and sacking of its capital Angkor by the Thais (1353, 1393, and 1431). They were unified by Ramadhipathi to found the kingdom of Ayutthaya.

Faced with the assaults of the Thais, the Khmers had to abandon their capital Angkor and retreat to the geographic heart of their country, the Four Arms of the Mekong (Phnom Penh), with the last king of the Khmer empire and the first king of Cambodia, Ponhea Yat. This strategic and economic retreat is only one of the hypotheses suggested by researchers to hasten the decline of Angkor. But according to recent discoveries reported by National Geographic in its issue 118 of July 2009, the collapse of Angkor is largely due to climatic disasters that managed to destroy the most complex and ingenious hydraulic system, a jewel of Khmer civilization. The imperial city of Angkor had to face severe successive droughts from 1362 to 1392 and from 1415 to 1440, thanks to the analysis of growth rings found in certain long-lived cypresses such as teak or Siam wood.

When the hydraulic system began to malfunction, showing signs of weakness, the power of the Angkorian empire did the same. This is why, being the first to realize the importance of this system, the archaeologist Bernard Philippe Groslier of the French School of the Far East (EFEO) did not hesitate to describe Angkor as a « hydraulic city » when publishing his work in 1979. Designed to support religious rituals and ensure a constant water supply for rice cultivation, the gigantic barays (or water reservoirs) were drained in the event of successive major droughts. This could have dealt a fatal blow to this already faltering empire, weakened by internal divisions and successive Thai invasions, as Angkor was home to no less than 750,000 inhabitants over an area of about 1000 km². This brings to mind the period experienced by the Maya cities of Mexico and Central America, which succumbed to overpopulation and environmental degradation linked to three successive droughts in the 9th century. This disaster also brutally reminds us of the limits of human ingenuity, which can be easily overcome at any time by the forces of nature. Man cannot conquer nature under any circumstances but must become one with nature to live in harmony with it.

- Banteay Srei (a jewel of Khmer art)

- Ta Prohm (Temple-monastery)

- Bayon temple (Angkor Thom)

- Angkor Vat (Temple Mountain)

- Angkor: naissance d’un mythe avec Louis Delaporte (Musée Guimet,Paris)

Bibliographie.

Thierry Zéphir: L’empire des rois khmers; Découvertes Gallimard. 1997

Claude Jacques, Michael Freeman : Angkor, cité khmère. Book Guides

Bernard Philippe Groslier: Indochine. Editions Albin Michel 1961

National Geographic: Angkor . Pourquoi la grande cité médiévale du monde s’est effondrée? N° 118. Juillet 2009

Maria Albanese: Angkor. gloire et splendeur de l’empire khmer. Editions White Star

Georges Coedès: Cổ sử các quốc gia Ấn Độ Hóa ở Viễn Đông. Editions Thế Giới. 2011

Chu Đạt Quan: Chân Lạp phong thổ ký. Editions Thế Giới . 2011