Until today, the bronze drums continue to sow discord between the Vietnamese and Chinese scientific communities. For the Vietnamese, the bronze drums are the prodigious and ingenious invention of peasant metallurgists during the time of the Hùng kings, the founding fathers of the Văn Lang kingdom. It was in the Red River delta that the French archaeologist Louis Pajot unearthed several of these drums at Ðồng Sơn (Thanh Hoá province) in 1924, along with other remarkable objects (figurines, ceremonial daggers, axes, ornaments, etc.), thus providing evidence of a highly sophisticated bronze metallurgy and a culture dating back at least 600 years before Christ. The Vietnamese find not only their origin in this re-excavated culture (or Đông Sơn culture) but also the pride of reconnecting with the thread of their history. For the French researcher Jacques Népote, these drums become the national reference of the Vietnamese people. For the Chinese, the bronze drums were invented by the Pu/Liao (Bộc Việt), a Yue ethnic minority from Yunnan (Vân Nam). It is evident that the authorship of this invention belongs to them, aiming to demonstrate the success of the process of mixing and cultural exchange among the ethnic groups of China and to give China the opportunity to create and showcase the fascinating multi-ethnic culture of the Chinese nation.

Despite this bone of contention, the Vietnamese and the Chinese unanimously acknowledge that the area where the first bronze drums were invented encompasses only southern China and northern present-day Vietnam, although a large number of bronze drums have been continuously discovered across a wide geographical area including Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Indonesia, and the eastern Sunda Islands. Despite their dispersion and distribution over a very vast territory, fundamental cultural affinities are noted among populations that at first glance appear very different, some protohistoric and others almost contemporary. Initially, in the Chinese province of Yunnan where the Red River originates, the bronze drum has been attested since the 6th century BCE and continued to be used until the 1st century, just before the annexation of the Dian kingdom (Điền Quốc) by the Han (or Chinese). The bronze chests intended to contain local currency (or cowries), discovered at Shizhaishan (Jinning) and bearing on their upper part a multitude of figures or animals in sacrificial scenes, clearly testify to the indisputable affinities between the Dian kingdom and the Dongsonian culture.

Then among the populations of the Highlands (the Joraï, the Bahnar, or the Hodrung) in Vietnam, the drum cult is found at a recent date. Kept in the communal house built on stilts, the drum is taken down only to call the men to the buffalo sacrifice and funeral ceremonies. The eminent French anthropologist Yves Goudineau described and reported the sacrificial ceremony during his multiple observations among the Kantou of the Annamite Trường Sơn mountain range, a ceremony involving bronze drums (or Lakham) believed to ensure the circularity and progression of the rounds necessary for a cosmogonic refoundation.

These sacred instruments are perceived by the Kantou villagers as the legacy of a transcendence. The presence of these drums is also visible among the Karen of Burma. Finally, further from Vietnam, on the island of Alor (Eastern Sunda), the drum is used as an emblem of power and rank, as currency, as a wedding gift, etc. Here, the drum is known as the « mokko. » Its role is close to that of the bronze drums of Ðồng Sơn. Its prototype remains the famous « Moon of Pedjeng » (Bali), whose geometric decoration is close to the Dong Son tradition. This one is gigantic and nearly 2 meters high.

More than 65 citadels spread across the territories of the Bai Yue responded favorably to the call of the uprising led by the Vietnamese heroines Trưng Trắc and Trưng Nhị. Perhaps this is why, under Chinese domination, the Yue (which included the proto-Vietnamese or the Giao Chi) hid and buried all the bronze drums in the ground for fear of them being confiscated and destroyed by the radical method of Ma Yuan. This could explain the reason for the burial and location of a large number of bronze drums in the territory of the Bai Yue (Bách Việt) (Guangxi (Quảng Tây), Guangdong (Quảng Đông), Hunan (Hồ Nam), Yunnan (Vân Nam), Northern Vietnam (Bắc Bộ Vietnam)) during the conquest of the Qin and Han dynasties. The issuance of the edict by Empress Kao (Lữ Hậu) in 179 BC, stipulating that it was forbidden to deliver plowing instruments to the Yue, is not unrelated to the Yue’s reluctance towards forced assimilation by the Chinese.

In Chinese annals, bronze drums were mentioned with contempt because they belonged to southern barbarians (the Man Di or the Bai Yue). It was only from the Ming dynasty that the Chinese began to speak of them in a less arrogant tone after the Chinese ambassador Trần Lương Trung of the Yuan dynasty (or Mongols (Nguyên triều)) mentioned the drum in his poem entitled « Cảm sự (Resentment) » during his visit to Vietnam under the reign of King Trần Nhân Tôn (1291).

Bóng lòe gươm sắc lòng thêm đắng

Tiếng rộn trống đồng tóc đốm hoa.

The shimmering shadow of the sharp sword makes us more bitter

The tumultuous sound of the bronze drum makes our hair speckled with white.

He was frightened when he thought about the war started by the Vietnamese against the Mongols to the sound of their drum.

On the other hand, in Chinese poems, it is never recognized that the bronze drums are part of the cultural heritage of the Han. It is considered perfectly normal that they are the product of the people of the South (the Yue or the Man). This fact is not doubted many times in Chinese poems, some lines of which are excerpted below:

Ngõa bôi lưu hải khách

Ðồng cổ trại giang thần

Chén sành lưu khách biển

Trống đồng tế thần sông

The earthenware bowl holds back the traveling sailor,

The bronze drum announces the offering to the river spirit.

in the poem « Tiễn khách về Nam (Accompanying the traveler to the South) » by Hứa Hồn.

Thử dạ khả liên giang thượng nguyệt

Di ca đồng cổ bất thăng sầu !

Ðêm nay trăng sáng trên sông

Trống đồng hát rơ cho lòng buồn thương

or

The moon of this night shimmers on the river

The barbarians’ song to the sound of the drum arouses painful regrets.

in the poem titled « Thành Hà văn dĩ ca » by the famous Chinese poet of the Tang dynasty, Trần Vũ.

In 1924, a villager from Ðồng Sơn (Thanh Hoá) recovered a large number of objects including bronze drums after the soil was eroded by the flow of the Mã river. He sold them to the archaeologist Louis Pajot, who did not hesitate to report this fact to the French School of the Far East (École Française d’Extrême-Orient). They later asked him to be responsible for all excavation work at the Ðồng Sơn site.

But it was in Phủ Lý that the first drum was discovered in 1902. Other identical drums were acquired in 1903 at the Long Ðội Sơn bonzerie and in the village of Ngọc Lữ (Hà Nam province) by the French School of the Far East. During these archaeological excavations begun in 1924 around the Ðồng Sơn hill, it was realized that a strange culture with canoe-tombs was being uncovered.

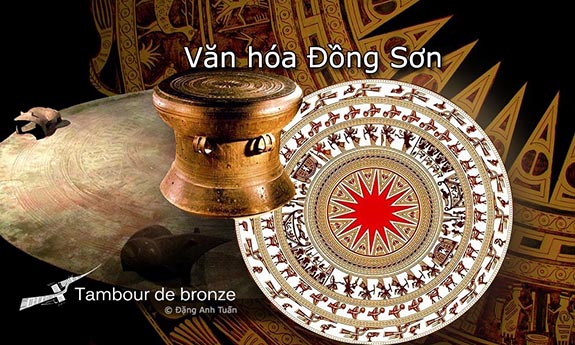

These are actually boats made from a single piece of wood, sometimes reaching up to 4.5 meters in length, each containing a deceased person surrounded by a whole set of funerary furniture: ornaments, halberds, parade daggers, axes, containers (situlas, vases, tripods), pottery, and musical instruments (bells, small bells). Moreover, in this funerary skiff are objects of quite large dimensions and recognizable: bronze drums, some measuring more than 90 cm in diameter and one meter in height. Their shape is generally very simple: a cylindrical box with a single slightly flared bottom forming the upper part of the drum. On this sounding surface, there is at its center a multi-pointed star which is struck with a mallet. Four double handles are attached to the body and the middle part of the drum to facilitate suspension or transport using metal chains or plant fiber ropes. These drums were cast using a clay mold, into which a bronze and lead alloy was poured.

The Austrian archaeologist Heine-Geldern was the first to propose the name of the Đồng Sơn site for this re-excavated culture. Since then, this culture has been known as « Dongsonian. » However, it is to the Austrian scholar Franz Heger that much credit is due for the classification of these drums. Based on 165 drums obtained through purchases, gifts, or accidental discoveries among bronze workers or ethnic minorities, he managed to accomplish a remarkable classification work that still has a significant influence in the global scientific community today, serving as an essential reference for the study of bronze drums. His work was compiled into two volumes (Alte Metaltrommeln aus Südostasien) published in Leipzig in 1902.