Version française

Version vietnamienne

Until today, the exact ethnic origin of the Chams is not known. Some believe that they came from continental Asia and were pushed back along with other populations living in southern China (the Bai Yue) by the Chinese, while others (ethnologists, anthropologists, and linguists) highlighted their island origin through their research work.

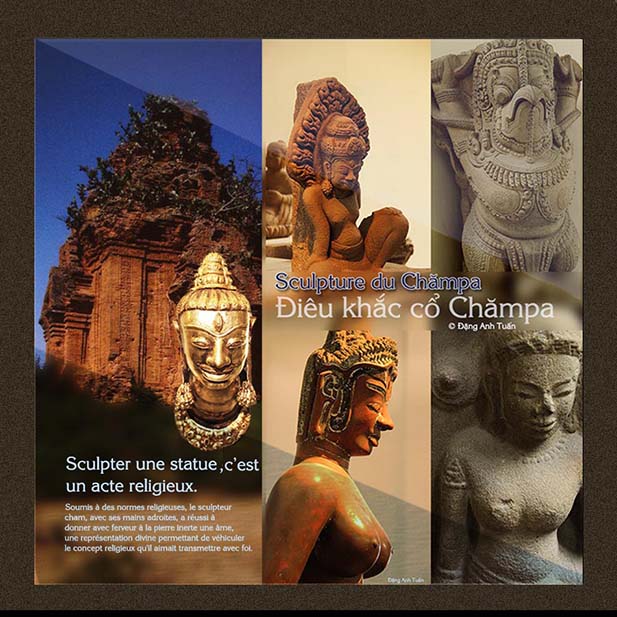

Carving a statue is a religious act.

For the latter, the Chams were probably populations from the South Seas (the countries of the archipelagos or those of the Malay Peninsula). Cham oral traditions mentioning connections linking, in legendary times, Champa and Java support this latter hypothesis.

Nicknamed the Vikings of Southeast Asia, the Chams lived along the coasts of central and southern present-day Vietnam. Their main activities were essentially based on trade. They were in contact very early with China and territories as far away as the Malay Peninsula, possibly the coasts of South India.

Being dedicated to religious purposes, Cham sculpture was thus not immune to political repercussions and influences from outside, particularly those from India, Cambodia, and Java. These became the main forces of creation, development, and evolution of styles in their art. According to the French researcher Jean Boisselier, Cham sculpture was closely linked to history. Significant changes were noted in the development of Cham sculpture, especially statuary, with historical events, changes of dynasties, or the relations that Champa had with its neighbors (Vietnam or Cambodia). According to the Vietnamese researcher Ngô Văn Doanh, whenever there was a significant external impact, a new style in Cham sculpture soon appeared.

To illustrate this, it is enough to cite an example: in the 11th-12th centuries, the intensification of violent contacts especially with Vietnam and Cambodia, and the emergence of new concepts related to the foundations of royal power can explain the originality and richness found in the style of Tháp Mắm.

Pictures gallery

Being the expression of the Indian pantheon (Brahmanist but especially Shaivist and Buddhist), Cham sculpture rather resorts to the local interpretation of concepts and norms coming from outside with elegance than to servile imitation. It is above all a support for meditation and a proof of devotion. Sculpting a statue is a religious act. Subject to religious norms, the Cham sculptor, with his skillful hands, succeeded in fervently giving the inert stone a soul, a divine representation allowing the conveyance of the religious concept he wished to transmit with faith. Cham sculpture is peaceful. No scenes of horror are depicted. There are only somewhat fanciful animal creatures (lions, dragons, birds, elephants, etc.). No violent or indecent forms are found in the deities. Despite the evolution of styles over history, Cham sculpture continues to maintain the same divine and animal creatures within a constant theme.

Makara

Cham art has succeeded in maintaining its specificity, its own facial expression, and its particular beauty without it being said that it is a servile copy of external models, thus preserving its uniqueness in Hindu sculpture found in India and Southeast Asia. Despite the lack of animation and realism, Cham works were mostly carved from sandstone and much more rarely from terracotta and other alloys (gold, silver, bronze, etc.).

Generally modest in size, they depict religious beliefs and worldviews. They cannot leave us indifferent because they always give us a strong strange impression. This is one of the characteristics of the beauty of Cham art.

In Cham sculpture, one finds free-standing sculptures (round-bosses), high reliefs, and low reliefs. A free-standing sculpture is one that can be viewed from all sides to see the sculptor’s work. A high relief is a sculpture with a very prominent relief that does not detach from the background. As for the low relief, it is a sculpture with slight projection on a uniform background. In Cham sculpture, there is a tendency to emphasize the roundness of creatures in the reliefs. Few scenes are depicted in this sculpture. There is a noted lack of connection or coherence in the assembly when otherwise.

The creatures found in Cham sculpture tend to always emerge brilliantly from the space surrounding them. They have something monumental about them. Even when they are grouped together in the works of Mỹ Sơn, Trà Kiệu depicting the daily life of the Chams, they give us the impression that each one remains independent from the others.

One can say that the Cham sculptor focuses solely on the creature he wants to show and deify without ever thinking about excessively unrealistic details and imperfections (such as the too-large hand or the overly bent arm of the dancer from Trà Kiệu, for example) and without closely imitating the original Indian models, which gives this Cham sculpture the « monumental » character not found in other sculptures. This is another particularity found in this Cham sculpture.

The works are not numerous but they testify to a beautiful plastic quality and the expression of various religions. It is difficult to attribute them to a single style. On the other hand, some traits close to the tradition of Indian art from Amaravati can be noted. It was only in the second half of the 7th century, under the reign of King Prakasadharma Vikrantavarman I, that Cham sculpture began to take shape and reveal its originality. [Reading more]