Version française

Version vietnamienne

It is called « Thầy or master » because it was here that the Buddhist monk Từ Đạo Hạnh invented and taught the local population a unique art form: water puppet theater. There is also the Côn Sơn pagoda located on the mountain of the same name, 60 km from Hanoi in Hải Dương province. Comprising about twenty buildings, it is nestled in the pine forest at the top of a staircase with several hundred steps. It was here, upon withdrawing from political life, that the famous humanist Nguyễn Trãi left us an unforgettable poem entitled « The Song of Côn Sơn (Côn Sơn Ca) » in which he described the magnificent landscape of this mountain and attempted to summarize the life of a man who can only last at most a hundred years and for whom everyone seeks what they desire before finally returning to grass and dust. But the most visited pagoda remains the Perfume Pagoda (Chùa Hương). This is actually a complex of buildings constructed in the mountain cliffs. Located 60 km southwest of the capital, it is one of the national sanctuaries frequented by most Vietnamese along with the Bà Chúa Xứ Pagoda (Châu Đốc) near the Cambodian border during the Tết festival.In central Vietnam, the pagoda of the Celestial Lady (Chùa Thiên Mụ), located opposite the Perfume River (sông Hương), is full of charm, while in the south, in Tây Ninh province, not far from Saigon, nestles on the Black Lady Mountain (núi Bà Đen) a pagoda bearing the same name.

In the capital Hanoi alone, there are at least 130 pagodas in the surrounding area. There are as many villages as there are pagodas. It is difficult to list them all. But due to the whims of time and the ravages caused by war, there are very few buildings that have managed to keep intact the architectural and sculptural style dating from the Lý, Trần, and Lê dynasties.

Sometimes human wrongdoing is responsible for the destruction of certain famous pagodas. This is the case of the Báo Thiên pagoda, whose site was ceded to the French colonial authorities for the construction of the neo-Gothic style Saint Joseph church that can be seen today in the heart of the capital, not far from the famous Lake of the Restored Sword (Hồ Hoàn Kiếm) (Hanoi). Generally speaking, most of today’s pagodas visibly bear traces of restoration and renovation under the Nguyễn dynasty. However, their ritual objects, stone and bronze statues have been less altered and have retained their original state over the centuries.Moreover, when moving into the central and southern parts of Vietnam, one realizes that Cham and Khmer influences are not absent in the architecture of the pagodas, as these territories formerly belonged respectively to the kingdoms of Champa and Funan.

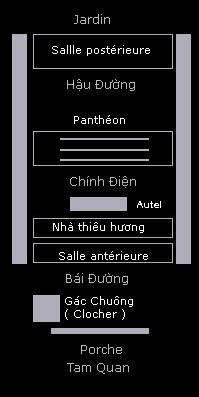

Despite the considerable number of pagodas and the variety of their sizes, the arrangement of their buildings remains unchanging. It is easy to recognize thanks to the following six famous Chinese characters: Nhất, Nhị, Tam, Đinh, Công, and Quốc (or 一, 二, 三, 丁, 工, and 国 in Chinese). Simplicity is visible in the model identified by the first character Nhất, where the buildings follow one single transverse row facing the porch (Tam Quan). This is what is found in most village pagodas that receive no state subsidies or in the Mekong Delta in southern Vietnam. The second character Nhị, meaning « two, » clearly recalls the arrangement of two parallel transverse rows facing the porch. This layout has the advantage of having at least three side doors and leads to a courtyard where vegetation is lush and omnipresent thanks to groves of shrubs and potted flowers. Sometimes there is a pond with lotuses and water lilies, which inevitably evokes serenity in harmony with nature.

With the third Tam character, there are three parallel transverse rows often connected in the middle by small bridges or a corridor. This is the case with the Kim Liên Pagoda (Hanoi) and Tây Phương Pagoda (Hà Tây). The first row corresponds to a group of buildings, the first of which is often called the « front hall » or tiền đường. Sometimes known by the Vietnamese name « bái đường, » this hall is used to receive all the faithful. It is protected at its entrance by guardian deities (or dvàrapalàs or hộ pháp) who, with threatening features, wear armor and display their weapons (halberd, helmet, etc.). Sometimes, alongside this front hall, the ten kings of hell (Thập điện diêm vương or Yamas) are enthroned, or in the corridor, the 18 arhats (Phật La Hán) in their various postures. This is the case in the Keo Pagoda (Chùa Keo), where the 18 arhats are present in the front hall. Sometimes there are also earth spirits or the protective spirit of the pagoda’s property (Đức Ông). One of the characteristics of the Vietnamese pagoda is the presence of the mother goddess Mẫu Hạnh (Liễu Hạnh Công Chúa), one of the four figures worshiped by the Vietnamese. Her veneration is visible, for example, in the front hall of the Mía Pagoda (Chùa Mía, Hà Tây). Then, in a second building slightly elevated compared to the first, there are incense burners as well as a stone stele recounting the history of the pagoda. That is why it is called « nhà thiêu hương (or incense burning hall). » It is also at the back of this building that there is an altar in front of which the monks recite prayers with the faithful while striking a wooden bell (mõ) and an inverted bronze bell (chuông). It is sometimes possible to find the bell in this group of buildings if the bell tower location (gác chuông) is not planned next to (or above) the porch. Regardless of the size of the pagoda, there must be at least three buildings in this first row.

After this, we come to the most important row of the pagoda, which corresponds to the main altar hall (thượng điện). This is where the pantheon, as rich as it is hierarchical, is located. It is spread over three pedestals. On the highest pedestal, against the back wall, is the altar of the Buddhas of the Three Eras (Tam Thế). On this altar, according to the Mahayana Buddhism conception (Phật Giáo Đại Thừa), are three statues representing the Past (Quá Khứ), the Present (Hiện Tại), and the Future (Vị Lai), each seated on a lotus throne. On the second pedestal, slightly lower than the first, sit the three statues known as the three existences, with Amitabha Buddha (Phật A Di Đà) in the middle, the Bodhisattva Avalokitecvara on the left (Bồ Tát Quan Âm), and the Bodhisattva Mahasthamaprapta on the right (Bồ Tát Đại Thế Chí). Generally, Amitabha Buddha is of a more imposing stature compared to the other two. Their presence reflects the importance that Vietnamese people place on the existence of the Pure Land (Tịnh Độ) in Buddhism.

This belief is so popular among Vietnamese people because, according to them, there exists the Western Paradise (Sukhàvati or Tây Phương cực lạc) presided over by the Buddha of Infinite Light (Amitabha), to which he guides the souls of the dead. By invoking his name, the devotee could access this paradise through their request for grace from the Bodhisattva Avalokitecvara acting as an intercessor. According to the Vietnamese researcher Nguyễn Thế Anh, it was the monk Thảo Đường, brought back to the country by King Lý Thánh Tôn during his military expedition to Champa (Đồng Dương), who proposed this method of enlightenment through intuition and the numbing of the mind by reciting the name of Buddha. This is also why Vietnamese Buddhists have the habit of saying A Di Đà (Amitabha) instead of the word « hello » when they meet.

Diagram of the interior arrangement of the

pagoda with the character Công

Finally, on the lowest and widest pedestal, larger than the other two, are Cakyamouni, the Buddha of the Present, and his two greatest disciples: Kasyapa (Đại Ca Diếp) and his cousin Ananda (Tôn Giả A Nan). In some pagodas, there is a fourth pedestal on which stands the Buddha of the Future, Maitreya, with the bodhisattva Samantabhadra (Phổ Hiền Bồ Tát), symbolizing practice on his right, and the bodhisattva Manjusri (Bồ Tát Văn Thù Sư Lợi), symbolizing wisdom on his left. The number of statues displayed on the altars varies depending on the fame of the pagoda in question. This is largely due to offerings from the faithful. This is the case with the Mía Pagoda (Chùa Mía), which has 287 statues, and the Trăm Gian Pagoda (Hà Tây) with 153 statues, etc.

As for the last row of the pagoda (or hậu đường), it corresponds to the rear hall and has a multifunctional character. Some pagodas reserve it for the residence of the monks (tăng đường). Others use it as a place of worship for spirits or heroes such as Mạc Đĩnh Chi (Chùa Dâu pagoda) or Đặng Tiến Đông (Trăm Gian pagoda, Hà Tây). This is why it is customary to say: tiền Phật hậu Thần (Buddha in front and Spirits behind). It is the opposite layout that should be found in a temple (đình): Tiền Thần, Hậu Phật (Spirits in front and Buddha behind). Sometimes there is a bell tower or a pavilion for the souls of the deceased.

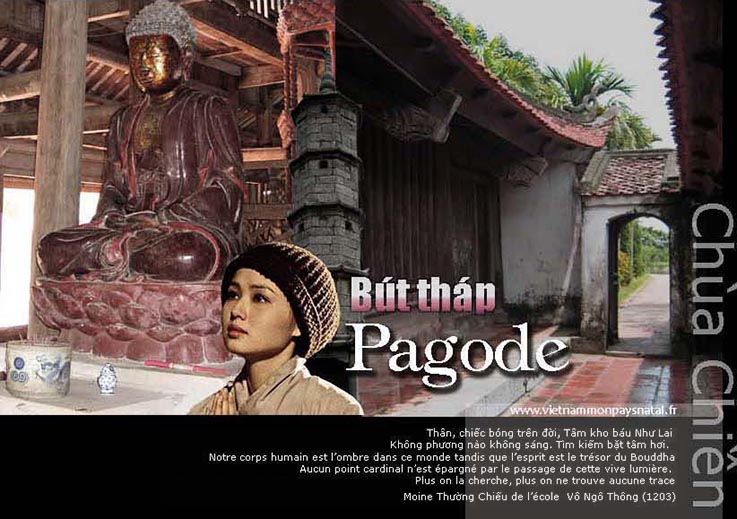

Sometimes, a room or an altar is reserved for those who have invested a lot of money in the construction or maintenance of the pagoda. Most of the donors were women, those who had a notable influence in state affairs. This is the case of Princess Mía, one of the concubines of Lord Trịnh. A special altar was reserved for her in the Mía pagoda, close to that of the Buddha. In the Bút Tháp pagoda, there is even a room dedicated to the veneration of female donors such as the great queen Trịnh Thị Ngọc Cúc, and the princesses Lê Thị Ngọc Duyên and Trịnh Thị Ngọc Cơ. These are figures who financially contributed to the construction of this pagoda in the 17th century.

In the backyard of the pagoda, one can find either a garden with stupas or a pond with water lilies. This is the case of the Phát Tích pagoda, whose backyard features 32 stupas of different sizes in its garden. Sometimes, the interior layout of the Vietnamese pagoda takes the shape of the character Đinh (丁). This is the fourth sign of the decimal cycle used in the Chinese calendar. This is the case of the Nhất Trụ pagoda, built by the Vietnamese king Lê Đại Hành in Hoa Lư (Ninh Bình), the ancient capital of Vietnam, and the Phúc Lâm pagoda (Tuyên Quang), erected under the Trần dynasty (13th-14th century).

The character that most Vietnamese pagodas often use in their interior layout remains the character Công (工). Besides the main rows detailed inside the pagoda, there are two long corridors connecting the front hall (tiền đường) to the rear hall (hậu đường). This creates a frame in the shape of a rectangle, thus encompassing the main rows previously mentioned in the character Tam. This arrangement has the appearance of the character Công inside the pagoda, but from the outside, it gives the impression of having the character Quốc (国) with the frame completed by the two long corridors.