Version française

Version vietnamienne

Galerie des photos

For a long time, I have hoped to one day visit the tomb of the exiled Emperor Hàm Nghi when I knew that he was buried in the commune of Thonac, located in the Dordogne department of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region. At the end of the week in May 2017, I had the opportunity to be in that area with my children, but I was completely disoriented and saddened when I found his vault. It continues to be ravaged by moss and does not resemble the photo found on the internet. We are all stunned and outraged by the lack of respect towards Hàm Nghi, a young emperor exiled at 18 by the French colonialists and who died in Algiers. Back in Paris, saddened by this story, I also did not have enough time to post the photos of Thonac on my site, especially those of the Château de Losse, whose owner is none other than the eldest daughter of Emperor Hàm Nghi, Princess Như Mây. She bought the castle in 1930 for the sum of 450,000 francs. Due to financial problems, she sold it to a Frenchman, who later transferred it to an English family in 1999. Today, this castle has been classified as a historic monument since 1932. For this reason, the remains of Emperor Hàm Nghi were brought back to France to Thonac during Algeria’s independence in 1965 and were reburied there with his family (his wife, his eldest daughter Như Mây, his only son Minh Đức, and his housekeeper)

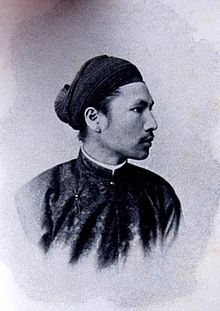

When mentioning King Hàm Nghi, one cannot forget to recall his biography. Known as Ưng Lịch, he was the younger brother of King Kiến Phúc. He was placed on the throne by two regents, Nguyễn Văn Tường and Tôn Thất Thuyết, in 1884 when he was 13 years old. Having killed three successive kings—Dục Đức, Hiệp Hoà, and Kiến Phúc—in less than a year, they thought that with Hàm Nghi’s young age, they could easily guide his governance toward a policy aimed at driving the French out of Vietnam. After the failure of the Vietnamese assault against the French garrison of General De Courcy at Mang Cá, King Hàm Nghi was forced to leave the citadel of Huế and took refuge in Quảng Trị in central Vietnam. He was accompanied by Tôn Thất Thuyết and Nguyễn Văn Tường. For an unknown reason, the latter returned to the citadel of Huế. He later tried to explain through his poem in which he acknowledged that he no longer followed Hàm Nghi in the resistance because, for him, it was preferable to serve the state rather than engage in resistance. For the king or for the Vietnamese state, the choice was difficult. He left it to future generations to judge.

Xe giá ngàn trùng lẫy dặm xanh

Lòng tôi riêng luyến chốn lan đình

Phải chăng phó mặc ngàn sau luận

Vua, nước đôi đường hỏi trọng khinh?

The carriage travels thousands of leagues through the vast green,

My heart alone longs for the place of the orchid pavilion.

Is it perhaps to entrust the judgment to thousands of years hence,

The king and the country, two paths questioning honor and disgrace?

He asked Father Caspar to contact De Courcy to arrange an audience and tried to convince him that he did not participate in the launch of the aborted assault. Pretending to believe him, De Courcy suggested that he write letters urging Hàm Nghi and his supporters to return to the citadel of Huế and set him an ultimatum of two months. After failing to convince Hàm Nghi and Tôn Thất Thuyết, he was first deported to Poulo Condor Island, then to Tahiti to receive treatment for his illness, and finally died in Papeete. As for Tôn Thất Thuyết, he continued to accompany Hàm Nghi in the fight against the French with his children Tôn Thất Đạm and Tôn Thất Thiệp during the four years of resistance. He eventually left for China to seek help from the Qing and died there in exile in 1913.

King Hàm Nghi twice called upon all the vital forces of the nation, especially the scholars, to rise up against the colonial authorities in his name through the movement called « Cần Vương » (Aid to the King) from the North to the South to demand independence. This movement began to find a favorable response among the people. The scale of this movement did not diminish and was visible everywhere, such as in Hà Tĩnh with Phan Đinh Phùng, Đinh Nho Hạnh, in Bình Định with Lê Trung Đình, in Thanh Thủy with Admiral Lê Trực, in Quảng Bình with Nguyễn Phạm Tuân, etc. The name of King Hàm Nghi accidentally became the banner of national independence. Despite the installation of Đồng Khánh on the throne by the French colonial authorities with the approval of the Queen Mother Từ Dũ (mother of Emperor Tự Đức), the insurrection movement continued to endure as long as King Hàm Nghi was still alive. To extinguish the insurrection everywhere, it was necessary to capture Hàm Nghi because he represented the soul of the people while the rebels were part of the body of this people. Once the soul of the people was eliminated, the body disappeared in an obvious way. Between Hàm Nghi and the rebels of the Cần Vương movement, there was always an intermediary who was none other than Tôn Thất Đạm, the son of Tôn Thất Thuyết. Few people had the right to approach Hàm Nghi, who was constantly protected by Tôn Thất Thiệp and a few Muong bodyguards of Trương Quang Ngọc.The latter was known as a local Mường lord living on the banks of the Nai River in Quảng Bình. Hàm Nghi led a difficult and miserable life in the forest during the resistance period.

Because of the betrayal of Trương Quang Ngọc, he was captured in November 1888 and taken back to the citadel of Huế. Silent, he categorically denied being King Hàm Nghi because for him it was an indescribable shame. He continued to remain not only impassive but also mute about his identity in the face of his French captors’ incessant interrogations. Several mandarins were sent to the site to identify whether the young captive in question was indeed King Hàm Nghi or not, but none managed to move him except the old scholar Nguyễn Thuận. Seeing the king who continued to play this charade, he, with tears in his eyes, prostrated himself before him and trembled as he dropped his cane. Faced with the sudden appearance of this scholar, the king forgot the role he had played until then against his captors, helped him up, and knelt before him: « I beg you, my master. » At that moment, he realized he had made a mistake in recognizing him because Nguyễn Thuận had been his tutor when he was still young. He never regretted this gesture because for him, respect for his master came before any other consideration.

Thanks to this recognition, the colonial authorities were certain to capture King Hàm Nghi, which allowed them to pacify Vietnam with the disappearance of the « Cần Vương » movement a few years later. He was then deported to Algeria at the age of 18. He never saw Vietnam again. Even his remains have not been brought back to Vietnam to this day due to his family’s refusal, but they were reburied in the village of Thonac in Sarlat (Dordogne, France) during Algeria’s declaration of independence in 1965 along with his family. During his exile in Algiers, he abandoned all political objectives from 1904, the year of his marriage to a French woman. This was revealed by his niece Amandine Dabat in her work titled « Hàm Nghi, Emperor in Exile and Artist in Algiers, » Sorbonne University Press, published on November 28, 2019. He found solace in another passion, another way of living through art. He was seen mingling with the artistic and intellectual circles of his time (Marius Reynaud, Auguste Rodin, Judith Gautier, etc.). Thanks to this association,

he became a student of the orientalist painter Marius Reynaud and the famous sculptor Auguste Rodin, which allowed him to overcome the eternal pain and sadness of a young patriotic emperor exiled far from his homeland until his death.

Référence bibliographique

Vua Hàm Nghi. Phan Trần Chúc Nhà xuất bản Thuận Hóa 1995.

Ham Nghi – Empereur en exil, artiste à Alger. Amandine Dabat, Sorbonne Université Presses, Novembre 2019