Tại sao các chùa Nhật Ban không bị sụp đổ khi có động đất?

Version française

Version anglaise

Galerie des photos

Đến xứ Nhật Bản, du khách thường có dịp đi tham quan các chùa Nhật bằng gỗ ở Nara và Kyoto. Qua nhiều trận động đất thường xuyên ở Nhật Bản, các chùa nầy vẫn đứng vững dù đã có trải qua hơn 1300 năm xây cất. Cũng như chùa Senso-ji 5 tầng ở Tokyo không phải bị phá hủy bởi động đất mà bị oanh tạc trong thời kỳ chiến tranh thế giới thứ hai. Như vậy có bí quyết nào khiến các chùa không bị sụp đổ và được bảo vệ trước sự tàn phá của động đất ? Đó là một câu hỏi mà chính mình cũng tự nêu ra khi đến tham quan các chùa như Senso-ji và Kiyomizu Dera. Theo kiến trúc sư Nhật Ueda Atsushi thì sự bảo vệ an toàn nầy được giải thích với chùa Hôryûji, một chùa Nhật có lâu đời nhất dựa trên các lý do như sau trong quyển Nipponia số 33. Trước hết là việc sử dụng vật liệu. Tất cả phần cấu trúc của chùa đều làm bằng gỗ. Nó có thể cong uốn nhưng không dễ bị gãy, đó là nhờ tính linh hoạt khiến nó có thể làm tiêu tan và thu hút năng lượng địa chấn. Kế đó là sự lựa chọn thiết kế kiến trúc. Không có một cây đinh nào trọng dụng ở các nơi nối các thanh trúc với nhau (như lỗ mộng, lưỡi gà vân vân..). Các đầu của các thanh trúc nầy được đục mỏng và hẹp hơn vào trong các khe khiến tạo ra một lề di chuyển, cọ xát lẫn nhau và kiềm chế lại được việc truyền năng lượng địa chấn lên đỉnh tháp.

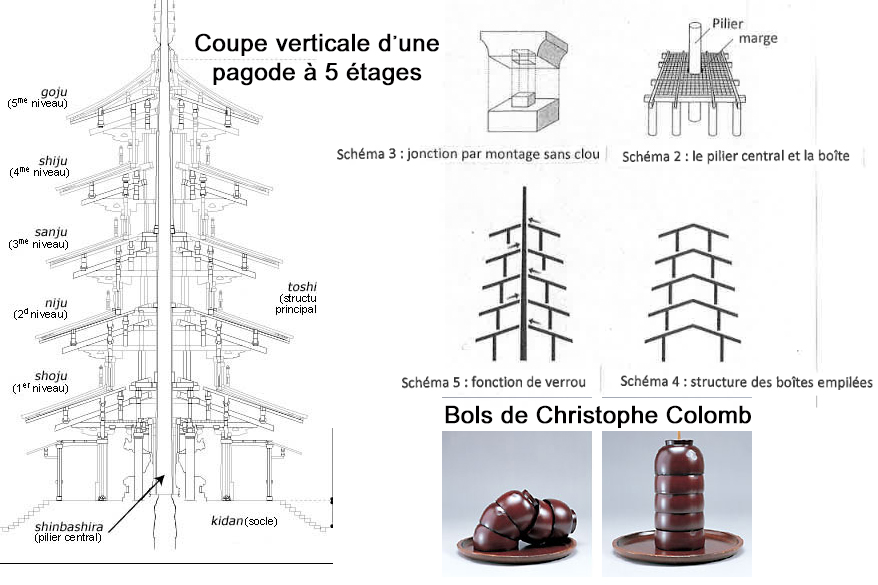

Với kỹ thuật nầy, một chùa Nhật Bản năm tầng như Senso-ji có ít nhất một ngàn thanh trúc nối với nhau qua các lỗ mộng. Hơn nữa, chùa có một cấu trúc có nhiều lớp hay nhiều hình hộp chồng lên, cái to ở dưới chót cái nhỏ ở trên cao mà người Nhật họ gọi là go-ju no to. Khi mặt đất rung chuyển thì các hộp từ từ đu đưa nhưng mỗi lớp của cái hộp hoàn toàn độc lập với các lớp khác khiến cho toàn bộ cấu trúc dễ « uốn nắn », linh hoạt như một con rắn vặn vẹo và tìm lại được lại sự thăng bằng như một món đồ chơi con lắc jaijirobe của người Nhật. Khi lớp hộp ở dưới xoay bên trái thì lớp hộp nắp trên xoay bên phải rồi trên nữa xoay bên trái …Nhưng sự thăng bằng nầy có thể bị phá vỡ nếu có một lớp nào tách rời xa quá trung tâm và nếu nó không được kéo về lại vị trí khiến làm toàn bộ cấu trúc sẽ sụp đổ. Đấy là trong trường hợp có một trận động đất cực kỳ quan trọng. Vì vậy để ngăn ngừa sự sụp đổ nầy mà cần có cây cột trụ lớn từ dưới đất lên tới đỉnh nằm ở trung tâm. Nó có nhiệm vụ là đưa về vị trí cũ một trong những lớp hộp nào muốn trượt ra khỏi ngoài.

Như thế cây cột trụ trung tâm (shinbashira) giữ vai trò chốt then và xem như một chiếc đũa mà được đâm xuyên qua ở dưới đích của 5 cái chén úp chồng lên nhau khiến các chén nầy khó mà bay ra ngoài. Các chén nầy được kiến trúc sư Nhật Ueda Atsushi gọi là các chén của Christophe Colomb » bằng cách tìm nguôn cảm hứng với quả trứng của Christophe Colomb. Quả trứng nầy đứng vững trên bàn sau khi một phần nhỏ của vỏ đã bị san phẳng ở một đầu của nó. Những kỷ thuật truyền thống của các chùa Nhật 5 tầng vẫn còn được trọng dụng và là nguồn cảm ứng không ít hiện nay cho các toà nhà cao ốc như ngọn tháp Tokyo Skytree.

De passage au Japon, le touriste a l’occasion de visiter les pagodes japonaises de Nara et Tokyo. Malgré la fréquence des séismes au Japon, ces pagodes continuent à tenir bon durant 1300 ans de leur construction. C’est le cas de la pagode Senso-ji à 5 étages. Celle-ci n’a jamais été détruite par le séisme mais elle a été anéantie entièrement par les bombardements durant la deuxième guerre mondiale. Quel est le secret pour ces pagodes de ne pas s’écrouler face à la dévastation provoquée par le séisme ? C’est aussi la question que je me pose moi-même sans cesse lors de la visite des pagodes Senso-ji (Tokyo) et Kiyomizu Dera (Kyoto). Selon l’architecte japonais Ueda Atsushi, l’entière protection trouve son explication avec la très ancienne pagode Hôryûji. Celle-ci est basée essentiellement sur les raisons suivantes trouvées dans le livre Nipponia n° 33. D’abord c’est l’utilisation du matériel. Toute la structure de la pagode a été faite avec du bois. Celui-ci peut être flexible mais il n’est pas cassable. Ce matériau de construction a la vertu d’être souple, ce qui permet de dissiper et d’absorber l’énergie sismique. Puis c’est le choix de la conception architecturale. Aucun clou n’est utilisé dans les réseaux de joints où les pièces de bois (comme les mortaises, les languettes etc…) peuvent être rabotées de façon mince et rétrécies dans les fentes, ce qui donne une large marge de déplacement et provoque le frottement entre ces pièces jouant ainsi un rôle de frein à la propagation sismique ver la partie haute de la pagode.

Avec cette technique, une pagode japonaise comme Senso-ji possède au moins un millier de joints assemblés par mortaises ou tenons. De plus la pagode a une structure en « couches ou boîtes superposées » où l’empilement s’effectue d’une manière progressive de bas en haut, de la plus grande à la plus petite au sommet de la pagode. Les Japonais désignent cette structure sous le nom « go-ju no to ». Quand la surface du sol commence à bouger, chaque boîte oscille indépendamment de ses voisines. La tour effectue une sorte de « danse de serpent » et retrouve son équilibre à l’état intial comme le jouet artisanal japonais jaijirobe. Quand la boîte formant l’étage inférieur a tendance à tourner vers la gauche, celle au dessus oscille vers la droite et celle au dessus encore vers la gauche … Cette manière à osciller peut provoquer un déséquilibre et aboutit à un écroulement de la structure lorsqu’une boîte s’écarte trop du centre et ne réussit pas à revenir à son état initial. C’est le cas où le tremblement de terre est très violent. Pour cela, il s’avère indispensable d’avoir au centre de la base de la pagode un gros pilier central (ou shinbashira) s’élançant du bas jusqu’au sommet pour empêcher le déséquilibre ainsi que l’écroulement de la structure. Ce pilier a pour rôle de ramener la « boîte empilée » à son état initial lorsque cette dernière s’éloigne trop du centre.

On peut dire que le pilier central ou (shinbashira) assume la fonction de verrou. Il est considéré comme une baguette transperçant au centre les fonds de cinq bols empilés à l’envers sur un plateau, ce qui les empêche de tout écartement. L’architecte japonais Ueda Atsushi désigne ces bols sous le nom des « bols de Christophe Colomb » en trouvant l’inspiration dans l’exemple de l’œuf de Christophe Colomb. Celui-ci peut se maintenir sur la table lorsqu’une petite partie de sa coquille est aplatie à l’une de ses extrémités. Les techniques classiques servant la construction des pagodes japonaises à 5 étages continuent à être employées encore aujourd’hui et constituent au moins une source d’inspiration pour les gratte-ciel. C’est le cas de la tour Tokyo Skytree.

When visiting Japan, tourists often have the opportunity to tour wooden Japanese temples in Nara and Kyoto. Despite the frequent earthquakes in Japan, these temples have stood firm even after more than 1,300 years of construction. Similarly, the five-story Senso-ji temple in Tokyo was not destroyed by earthquakes but was bombed during World War II. So, is there a secret that prevents these temples from collapsing and protects them from earthquake damage? That is a question I asked myself when visiting temples like Senso-ji and Kiyomizu-dera. According to Japanese architect Ueda Atsushi, this safety protection is explained with Hōryū-ji, one of the oldest Japanese temples, based on the following reasons in Nipponia magazine, issue 33. First is the use of materials. All structural parts of the temple are made of wood. It can bend and flex but is not easily broken; this flexibility allows it to dissipate and absorb seismic energy. Next is the choice of architectural design. Not a single nail is used in the joints connecting the wooden beams (such as mortise and tenon joints, tongue and groove, etc.). The ends of these beams are carved thinner and narrower into the slots, creating a margin for movement, rubbing against each other, and restraining the transmission of seismic energy to the top of the tower.

With this technique, a five-story Japanese temple like Senso-ji has at least one thousand bamboo beams connected to each other through mortise holes. Moreover, the temple has a structure with many layers or several stacked box shapes, the large one at the bottom and the small one at the top, which the Japanese call go-ju no to. When the ground shakes, the boxes sway slowly, but each layer of the box is completely independent of the others, making the entire structure easy to « bend, » flexible like a twisting snake, and regains balance like a Japanese Jaijirobe pendulum toy. When the bottom box layer turns left, the next layer above turns right, then the one above that turns left… However, this balance can be disrupted if any layer moves too far from the center and is not pulled back into position, causing the whole structure to collapse. This is in the case of a very significant earthquake. Therefore, to prevent this collapse, a large pillar from the ground up to the top is needed at the center. Its role is to bring back into place any of the box layers that want to slip out.

The central pillar or (shinbashira) can be said to act as a lock. It is considered a rod piercing the bottoms of five bowls stacked upside down on a tray, preventing them from moving apart. Japanese architect Ueda Atsushi called these bowls « Christopher Columbus bowls, » drawing inspiration from the example of Christopher Columbus’s egg. The egg can stay on the table when a small part of its shell is flattened at one end. Classical techniques used to build five-story Japanese pagodas continue to be used today and are at least one source of inspiration for skyscrapers. This is the case for the Tokyo Skytree tower.