Under the Han dynasty, Chinese society was structured in such a way that only the literati and peasants were well respected compared to artisans and merchants, according to the Hanshu by Ban Gu in the 1st century. Yet, it was only the latter who benefited from the empire’s economic system despite a large number of restrictions imposed by the imperial power. The multiplication of private enterprises and the opening of trade routes (such as the Silk Road) allowed them to enrich themselves easily. They sold commodities and luxurious superfluous goods highly prized by the Han aristocracy and landowners. Thanks to funerary art, we are led to draw useful lessons about the art of living as well as entertainment of that era. Silk was reserved for the court, nobility, and officials, while linen was for the people, in their traditional costume adorned with accessories illustrating their social status. Silk experienced remarkable growth because it was the subject of luxury trade but was also used in the tribute system for the Xiongnu and vassal states. In 1 BC, silk gifts reached their maximum with 370 garments, 30,000 rolls of silk fabrics, and 30,000 jin of silk floss. Merchants took advantage of exchanges to launch a lucrative trade with foreigners, particularly with the Parthians and the Romans.

Private workshops competed with imperial workshops.

Funerary banner found in Madame Dai’s coffin

This encouraged silk production and increased regional diversity. The weaving demonstrates a high level of technical skill, as a silk shirt measuring 1.28 meters long with a wingspan of 1.90 meters found in the tomb of Marquise Dai weighed only 49 grams. Besides the silk banner covering the deceased’s coffin and decorated with paintings illustrating Taoist cosmology, silk manuscripts were also discovered (Yijing (Di Kinh), two copies of Daodejing (Đạo Đức Kinh), two medical treatises, and two texts on Yin-Yang, as well as three maps in one of the three Mawangdui tombs, some written in a mixture of lishu (scribe script) and xiaozhuan (small seal script) dating from the reign of Gaozu (Hán Cao Tổ), others entirely in lishu dating from the reign of Wendi. Despite its high cost, silk was preferred because it is more manageable, lighter, and easier to transport compared to wooden tablets. Under the Han, lacquerware, whose craftsmanship is still considered refined, began to fill the homes of the wealthy. These, imitating the aristocracy of the Chu kingdom, used lacquered wooden tableware, most often red on the inside and black on the outside with enhanced painted motifs; these colors corresponded well to those of Yin (black) and Yang (red).

The same applies to trays and boxes intended for storing folded clothes, toiletries, manuscripts, etc. For princely families, jade replaces lacquer. As for the common people, ceramics are used along with wood for their tableware. Resembling individual circular or rectangular trays, low tables, generally on legs, are used to serve meals. These are well stocked with dishes, chopsticks (kuaizi), spoons, ear-handled cups (erbei) for drinking water and alcohol. Regarding staple foods, millet and rice are the most appreciated cereals.

Millet is reserved for festive days in northern China, while rice, a product of the ancient kingdom of Chu, is confined to southern China as it is considered a luxury product. For the poor, wheat and soybeans remain dominant in their meals. Chinese cuisine is roughly the same as it was during the Qin era. Geng, a type of stew, remains the traditional Chinese dish where pieces of meat and vegetables are mixed. However, following territorial expansion and the arrival and acclimatization of new products from other parts of the empire, innovations gradually begin to appear in the making of noodles, steamed dishes, and cakes made from wheat flour.

The same applies to trays and boxes intended for storing folded clothes, toiletries, manuscripts, etc. For princely families, jade replaces lacquer. As for common people, ceramics are used along with wood for their tableware. Similar to individual circular or rectangular trays, low tables, generally with legs, are used for serving meals. These are well stocked with dishes, chopsticks (kuaizi), spoons, ear-handled cups (erbei) for drinking water and alcohol. Regarding staple foods, millet and rice are the most appreciated cereals.

Millet is reserved for festive days in northern China, while rice, a product of the ancient kingdom of Chu, is confined to southern China as it is considered a luxury product. For the poor, wheat and soybeans remain dominant in their meals. Chinese cuisine is roughly the same as it was during the Qin era. Geng, a type of stew, remains the traditional Chinese dish where pieces of meat and vegetables are mixed. However, following territorial expansion and the arrival and acclimatization of new products from other parts of the empire, innovations gradually begin to appear in the making of noodles, steamed dishes, as well as cakes made from wheat flour.

Roasting, boiling, frying, stewing, and steaming are among the cooking methods. The mat is used for sitting by all social classes until the end of the dynasty. It is held in place at the four corners by small bronze weights shaped like curled-up animals: tigers, leopards, deer, sheep, etc. To alleviate the discomfort caused by kneeling on the heels, lacquered wooden backrests or armrests are used. The mat is also used in central and southern China by modest people for sleeping. However, in northern China, because of the cold, one must use a kang, a kind of earthen bed covered with bricks and topped with mats and blankets. Beneath this kang, there is a system of pipes that distribute heat maintained from a stove located inside or outside the house.

Leisure and pleasures were not forgotten either during the Han period.

Thanks to texts, we know that the musical tradition of Chu held an important place in the Han court, which continued to appreciate it. According to the French sinologist J.P. Diény, the Han preferred above all other music that which made one cry. The favorite themes in songs revolved around separation, the passage of time, and pleasures.

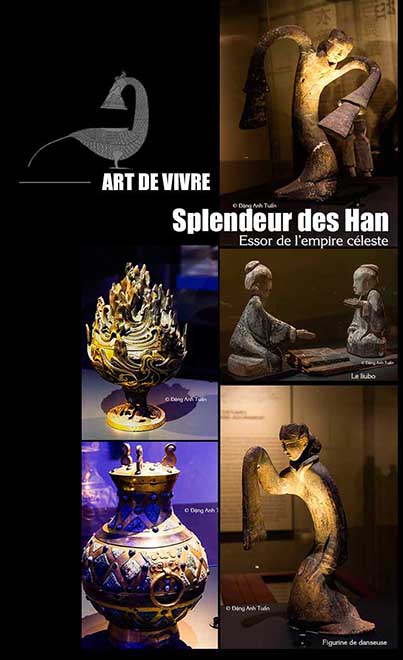

It is in the princely tombs that one discovers the figurines of dancers (mingqi) (minh khí). These reveal, through their gestures, the skill of tracing arabesques in the air with the long sleeves of their robes. The dances, based on the movements of the garments caused by the twisting of the body and the arms, give the dancer, accompanied by sometimes melancholic singing, a vivid portrait of Han choreographic art. For the latter, the family is, in the Confucian conception, the basic unit of the social system around which ancestor worship, rites, banquets, and weddings take place, providing throughout the year many occasions and pretexts for music to accompany them and make life harmonious. Being symbols of authority and power, bronze chimes cannot be absent. They are frequently used in ritual ceremonies but also in court music. Thanks to archaeological excavations, it is known that the life of Han princely courts was punctuated by banquets, games, and concerts accompanied by dances and acrobatics. As for entertainment, it was reserved exclusively for men. Liubo (a kind of chess game) was one of the most popular games of the time, along with dice games that could have up to 18 faces. It is better to play than to remain idle, this is the advice of Confucius given in his « Analects. »

Unlike the archaeology of earlier periods, that of the Han allows us to access the realm of the intimate, such as women’s makeup. They used foundation made from rice powder or white lead to paint their faces. Red spots were applied on the cheekbones, dark circles under the eyes, beauty marks on the cheek, a touch of color on the lips, etc. The education of the young was a priority during the Han period. From childhood, obedience, politeness, and respect for elders were instilled. At ten years old, the boy began receiving lessons from a teacher. He had to study the Analects of Confucius (Lunyu), the Classic of Filial Piety (Xiao jing), etc., before moving on between the ages of fifteen and twenty to reading the Classics. Considered inferior to men, women were obliged from a young age to learn silk work, cooking, and to possess the major qualities taught to them: gentleness, humility, self-control. They had to submit to the three obediences (Tam Tòng): as a child to their father, as a wife to their husband, as a widow to their son. They could be married around 14-15 years old to ensure the continuity of the family lineage. Despite these Confucian constraints, women continued to exercise real power within the family structure, particularly in the relationship between mother and son.The concern to honor the deceased led the Han, particularly those of the West, to create extravagant tombs and true treasures such as jade burial suits in the quest for immortality. This is the case with the tomb of Emperor Wudi’s father, Han Jing Di.

So far, archaeologists have already extracted more than 40,000 funerary objects around the emperor’s mound. It is expected that this entire funerary complex will yield between 300,000 and 500,000 objects because, besides the mound, there are two distinct pits left to explore: those of the empress and the emperor’s favorite concubine, Li. According to a Chinese archaeologist in charge of this exploration, it is not the number of objects discovered that is important, but rather the significance of each of the findings recovered in this funerary complex. It is believed that the Western Han were accustomed to valuing truly grandiose funerary monuments despite their frugality, revealed through a series of objects that are much smaller than those found in Qin tombs.