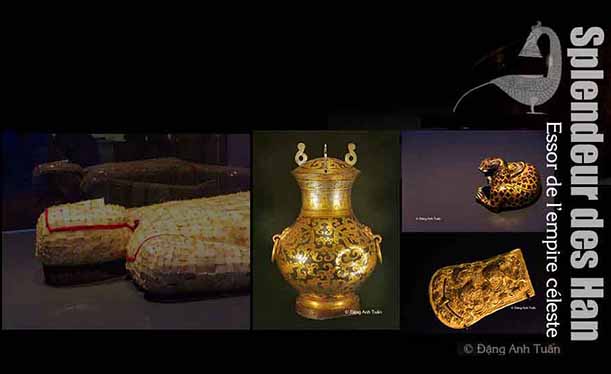

Niên đại nhà Đông Hán

Vietnamese version

French version

In the territories conquered by the Han, especially in southern China, sinicization continued at full speed. That is why revolts first followed one another in the kingdom of Dian (86, 83 BC, from 40 to 45 AD). They were harshly suppressed. These uprisings were largely due to the abuses of Han officials and the behavior of Chinese settlers who took possession of fertile lands and pushed local populations into the remote corners of their territory. Moreover, these populations had to adopt the language, customs, and religious beliefs of the sons of Han.

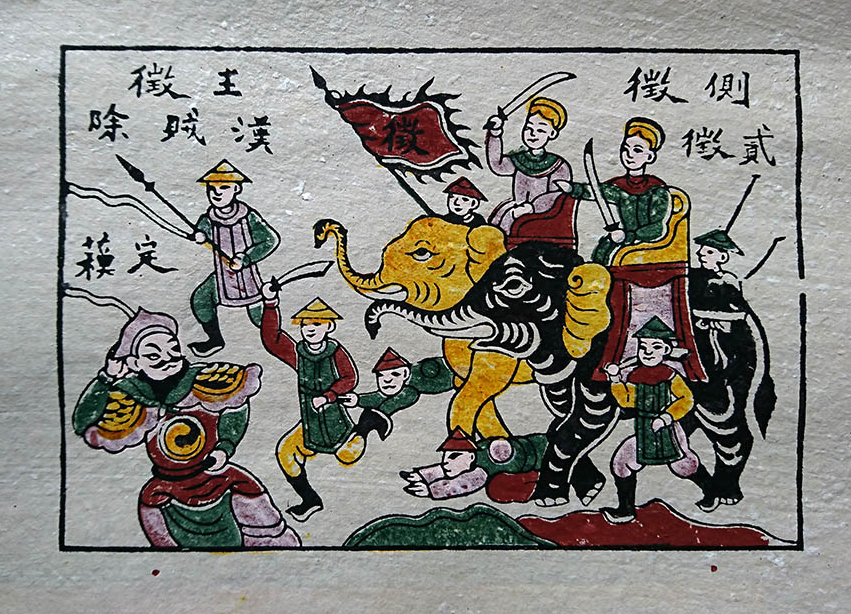

The revolt of the two sisters Trưng Trắc and Trưng Nhị

In the year 40, a serious rebellion broke out in the Jiaozhou province (or Giao Châu in Vietnamese), which at that time included part of the territories of Kouang Si (Quảng Tây) and Kouang Tong (Quảng Đông). It was led by the daughters of a local prefect, Trưng Trắc (Zheng Cè), the elder, and Trưng Nhị (Zheng Èr), the younger. Since the elder’s husband Shi Suo (Thi Sách) opposed the Chinese assimilation policy brutally enforced by the Chinese proconsul Tô Định (Su Ding), the latter did not hesitate to execute him as an example against the Yue insurgents, notably the Vietnamese. This exemplary execution outraged the Trưng sisters and immediately triggered the insurrection movement in the Yue territories. The two Trưng sisters managed to capture 65 citadels in a very short time. They proclaimed themselves queens over the conquered territories and established themselves in Meiling (or Mê Linh). In the year 41, they were defeated by General Ma Yuan (Mã Viện, Phục Ba Tướng Quân) (Tamer of the Waves) and chose suicide over surrender by throwing themselves into the Hát River.

They thus became the symbol of the Vietnamese resistance. They continue to be revered today not only in Vietnam but also in certain areas of the Yue territories of China (Guangxi and Guangdong). Ma Yuan began to implement a policy of terror and forced Sinicization by placing trusted Chinese men at all levels of administration and imposing Chinese as the official language throughout the Vietnamese territory. This was the first Chinese domination lasting nearly 1000 years before the liberation war initiated by General Ngô Quyền. Meanwhile, Guangwudi succeeded in bringing prosperity and stability to his empire by reducing the tax from one-tenth to one-thirtieth of the harvests and profits. After his death, his son, analogous to Han Wudi, Emperor Mingdi, continued the expansion policy by launching an offensive against the northern Xiongnu with the aim of freeing the Central Asian states from their control and restoring the security of the Silk Road for the benefit of China. General Ban Chao (Ban Siêu), brother of the historian Ban Gu of that time, was in charge of this military expedition. He succeeded in reaching the Caspian Sea and subjugating the Yuezhi with the help of the Kusana.

From the year 91, Mingdi’s China controlled the caravan routes of the Silk Road in the Tarim Basin. Through this route, Mingdi’s envoys brought back from Tianzu (Tây Vực) the effigies of Buddha after the emperor had seen them in his dream. Buddhism thus began to be introduced into China with the establishment of the White Horse Temple (Chùa Bạch Mã). China was separated only from the Roman Empire (Da Qin) by the Parthian kingdom (ancient Persia). Despite his territorial exploits, Mingdi (Minh Đế) did not leave in the Han historiography the image of a brilliant emperor like his father Guangwudi or his son Zhandi (75-88), adorned with all virtues, because during his reign, a peasant revolt took place in the year 60 due to the burden of corvée labor, public works for the consolidation of the Yellow River dikes, and the construction of the new Northern Palace, which was considered excessive and costly. Lacking stature, Zhandi’s successors were unable to follow the path of their predecessors.

They became pawns in court intrigues led by eunuchs and literate officials, while in the provinces, landowners began to usurp governmental prerogatives and raise private armies. The disintegration of the Han Empire became increasingly inevitable. In the year 189, the massacre of 2,000 eunuchs ordered by the military leader Yuan Shao (Viên Thiệu) clearly illustrated the disorder in the Han court. This slaughter was followed by the deposition of Emperor Shaodi (Hán Thiếu Đế) by the cruel general Dong Zhuo (Đổng Trác). This led to a period of turmoil and political disorder where each military leader tried his luck to seize the empire. Three generals, Cao Cao (Tào Tháo), Liu Bei (Lưu Bị), and Sun Quan (Tôn Kiên), who stood out among these military men and became famous for their victories, shared the Han Empire for nearly a century. This marked the end of the centralized state and the beginning of the Three Kingdoms period (Tam Quốc).

Chronology of the Eastern Han (Đông Hán)

25-57: Reign of Guangwu

57-75: Reign of Mingdi

75-88: Reign of Zhandi

88-106: Reign of Heidi

106: Reign of Shangdi

106-125: Reign of Andi

125: Reign of Shaodi

125-144: Reign of Chongdi

145-146: Reign of Zhidi

146-168: Reign of Huandi

168-189: Reign of Lingdi

184: Yellow Turban Rebellion

189: Deposition of Shaodi

189-220: Reign of Xiandi

190: Rise and power of General Cao Cao (Tào Tháo)

220: Death of Cao Cao and Xiandi

End of the Han dynasty

220-316: Period of the Three Kingdoms (Tam Quốc)

It is a dynasty that, after four centuries (from 206 BC to 220 AD) of its existence, opened the door of its empire to Confucianism. As a philosophical doctrine, it has left modern China a spiritual and moral heritage that continues to have a significant influence on millions of Asians. It is also a period rich in events and artistic and scientific innovations in a China that was both radiant and conquering. This is why the Chinese feel more than ever that they are the Sons of Han, as the latter gave them a crucial moment in the formation and radiance of their identity.