Thân là nguồn sinh diệt, Pháp tính vẫn như xưa

We are subject to the laws of birth and death.

But the nature of the Buddha remains the same over time.

Zen monk Thuần Chân of the Vinitaruci sect (1101)

Version vietnamienne

Version française

Unlike the word Đền (or temple), which refers to the place where a famous person (hero, king, or deity) is venerated, the word « Chùa » (or pagoda) is used solely to indicate the place where Buddha is honored. Before constructing this building, it is essential to carefully examine its location because it needs to be erected in harmony with the surrounding nature. However, unlike pagodas found in China, India, or Cambodia, monumentality and grandeur are not among the selection criteria for this construction. That is why the basic materials used are primarily wood, brick, and tile. The pagoda does not necessarily dominate the surrounding buildings. It can be found in almost every village. Similar to the communal house (or đình), it revives for most Vietnamese people the image of their village and, by extension, that of their homeland. It continues to exert a captivating appeal on them.

It is more visited than the communal house because no hierarchical barrier is visible there. It is absolute equality among humans, the motto preached by Buddha himself for sharing and delivering human suffering. Even in this serious and solemn setting, one sometimes finds classical theater performances (hát bội) in its courtyard. This is not the case with the people’s house (or communal house) where notability must be strictly respected. Hierarchical discrimination is more or less visible. Even the authority of the king (Phép vua thua lệ làng) cannot influence this village custom. That is why the pagoda is closer than ever to the Vietnamese. It is customary to say: Đất vua, Chùa làng, phong cảnh Bụt (The land belongs to the king, the pagoda to the village, the landscape to Buddha) to recall not only the closeness and the privileged and intimate connection of the pagoda with its villagers but also the harmony with nature.

![]()

Its role is predominant in the social life of the village, so much so that the pagoda is often mentioned in popular poems:

Ðầu làng có một cây đa,

Cuối làng cây thị, đàng xa ngôi chùa.

There is a banyan tree at the top of the village,

At the other end, there is a golden apple tree, and further away, a pagoda.

or

Rủ nhau xuống bể mò cua,

Lên non bẻ củi, vào chùa nghe kinh.

Rushing down to the sea to feel for crabs,

Climbing the mountain to gather firewood, entering the pagoda to listen to the sutras.

This shows how deeply attached the Vietnamese are to the sea and the mountain for sustenance and to the pagoda for spiritual nourishment. The pagoda is, in a way, their ideal and spiritual refuge in the face of natural calamities and the uncertainties they often encounter in their daily lives.

Until today, the origin of the word « Chùa » has not yet been clarified. No connection has been found in the etymology of the Chinese word « tự » (pagoda). According to some specialists, its origin should be sought in the Pali word « thupa » or « stupa » written in Sanskrit, because at the beginning of its construction, the Vietnamese pagoda resembled a stupa. Since the Vietnamese are accustomed to shortening the syllabic pronunciation of foreign-imported words, the word « stupa » thus became the word « stu » or « thu, » quickly evolving over the years into the word « chùa. » According to the Vietnamese researcher Hà Văn Tấn, this is only a hypothesis.

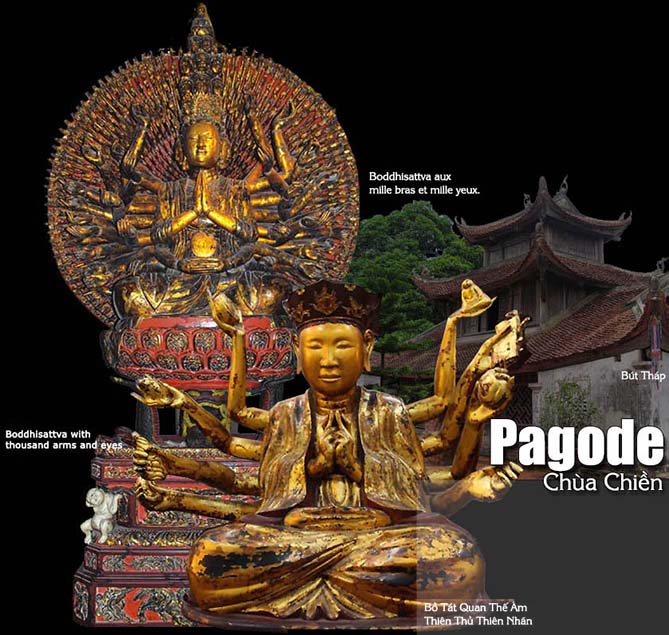

As for the word « Chiền » found in the ancient Vietnamese language (tiếng Việt cổ), it is used today in association with the word « Chùa » to refer to pagoda architecture. However, this word « Chiền » was often mentioned alone in the past to designate the pagoda. This is what was found in the poem titled « Chiền vắng âm thanh (deserted pagoda, solitary refuge) » by King Trần Nhân Tôn or that of Nguyễn Trãi « Cảnh ở tự chiền (or Landscape of the pagoda). » For many people, this word « Chiền » originates either from the Pali word « cetiya » or from the Sanskrit word « Caitya » to designate, in any case, the altar of the Buddha.

The construction of the pagoda requires as much time as effort in the preliminary research and exploration of the land. The site must strictly meet a certain number of criteria defined in geomancy because, according to the Vietnamese, this science could exert either a harmful or beneficial influence on the social life of villagers. The monk Khổng Lộ of the Vô Ngôn Thông sect (1016-1094), advisor to the Lý dynasty, had the opportunity to address this subject in one of his poems with the following verse: Tuyển đắc long xà địa khả cư (Choosing the land of dragons and snakes allows for peaceful dwelling) (or the choice of the best land can bring daily comfort in life).

We are used to building the pagoda either on a hill or a mound or on a sufficiently elevated area so that it can overlook the villagers’ homes. That is why the expression « Lên Chùa (or going to the pagoda), » undeniably linked to the topography of the pagoda, is commonly used by Vietnamese people even when the building in question is located on flat ground.

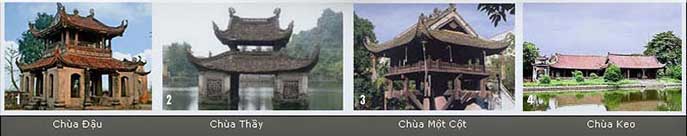

In most pagodas, especially those located in the North of Vietnam, the setting is both serene, mystical, and magnificent. Watercourses, mountains, hills, streams, etc., are always present, sometimes creating breathtaking landscapes due to their harmonious integration with nature. This is the case of the Master’s Pagoda (Chùa Thầy) between mountain and water. It perches on Mount Thầy in Hà Tây province, 20 km from the capital Hanoi.