Version française

Version vietnamienne

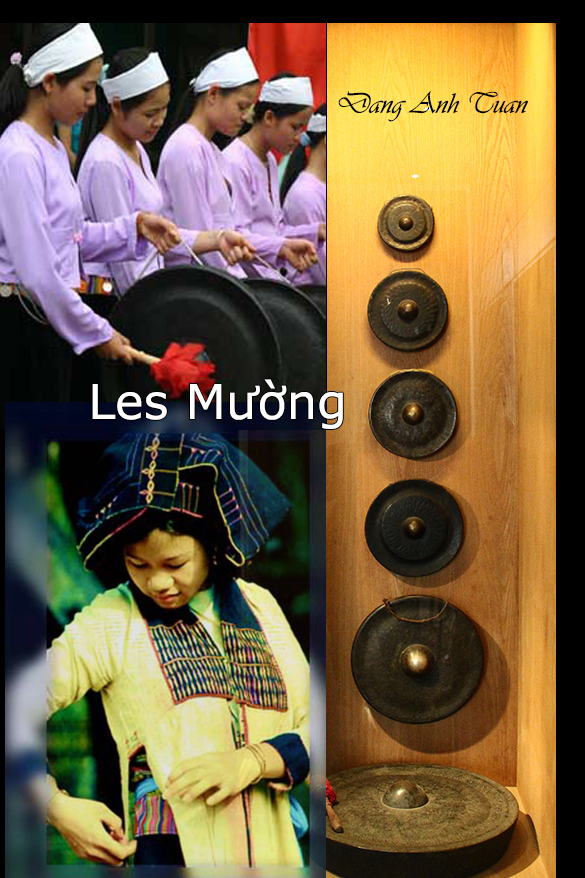

Being the third largest minority in today’s Vietnam by number (estimated at 1.4 million people), the Mường have long been established in the provinces of Hoà Bình, Thanh Hoá, Phú Thọ, Sơn La, Ninh Bình, etc.

According to the worthy Vietnamese successor of the French ethnologist Jeanne Cuisinier, Trần Từ (or Nguyễn Đức Từ Chi), the word Mường is used by the Vietnamese (or the Kinh) to designate the region where there are several Mường villages. The Vietnamese take advantage of this usage to name this people. They often refer to themselves by a name related to the region where they live: mol, moan in Hoà Bình, mwanl in Thanh Hoá, or Mol, Monl in Thanh Sơn, and it precisely means « người » (person, individual).

By delving into the narrative of their creation myth (Ngu Kơ and Lương Wong) and that of the Vietnamese (Âu Cơ – Lạc Long Quân), one realizes that they might have originated from the same people whom history and geography divided into two groups around the 9th-10th centuries: the first consisting of the Vietnamese who moved down to the plains and underwent strong Chinese influence, and the other composed of the Mường who remained in the most remote corners of the mountainous regions and received strong influence from the Thai who were massively pushed south of Chinese territory. This is why the Mường continue to be closer to the Vietnamese in terms of language. They belong to the same Việt-Mường group of the Austroasiatic language family (Ngữ hệ Nam Á), which also includes the Mon-Khmer subfamily. This is the origin of the tones in Vietnamese (6 tones) that allowed the French scholar A.G. Haudricourt to affirm in his 1954 work the belonging of Vietnamese to the Austroasiatic languages, an opinion now commonly shared by many foreign researchers and Vietnamese linguists. The French ethnologist Christine Hemmet from the Musée de l’Homme (Paris) reiterated this affiliation during a conference on May 18, 2000, on ethnic plurality, multilingualism, and the development of Vietnam.

Then this Việt-Mường group split into two independent languages: Vietnamese and Mường from the 14th to the 16th century. With Chinese and French borrowings, the former managed to experience at the beginning of the 20th century a remarkable development with its quốc ngữ in the field of Vietnamese literature where it succeeded in expressing all the nuances of thought and feeling in all aspects of life (1). As for the latter, it was isolated from foreign influence and remained in the state that it has today. This Mường language is found, that of the Vietnamese of old (or Proto-Vietnamese). For the Mường, the Vietnamese (or Kinh) descend from common ancestors and share the same blood as them. That is why they are accustomed to saying in one of their popular songs the following two lines:

Though you and I are TWO,

You and I, though ONE, become TWO.

Although you and I are TWO beings, we are but ONE.

Being ONE single being, you and I could always be considered as TWO.

It is also in one of the Muong legends (Đức Thánh Tản Viên) that we find the repeated struggles between the water and mountain spirits mentioned by the Vietnamese in their famous legend « Sơn Tinh Thủy Tinh. » This clearly shows how close the Vietnamese and the Muong are, despite their different destinies, to the point that even their legends are not so distinct. Two famous Vietnamese kings came from the Muong (Lê Đại Hành and Lê Lợi). However, in terms of social and cultural organization, the Muong today are closer to the Thái and the Tày.

The territory inhabited by the Muong is divided into regions (or mường) whose chiefs are lords called « lang cun, » each comprising 20 or 30 hamlets. These are led by « lang đạo, » descendants of the heroic founders of these hamlets, and are named according to their topographical situation: Xóm Ðác (hamlet next to a waterfall), Xóm Ðung (hamlet near the forest), Xóm Ðôn (hamlet on a hill), Xóm Thung (hamlet in a valley), or according to the names of familiar fruit trees: Xóm Trạch (bamboo hamlet), Xóm Mít (jackfruit hamlet), etc., or according to the names of animals: Xóm Hò (Turtle hamlet), Xóm Oong (Bee hamlet), etc., or according to the categories of Muong society: Xóm Chiềng (hamlet where the lang cun (or feudal lord) lives), Xóm Roong (hamlet belonging to farmers).

In traditional Mường society, the establishment of an oligarchy can be seen. This system, called NHÀ LANG in Vietnamese, is essentially based on the right of the first occupant to own the land, forests, and rivers, to cultivate them, and to bequeath them always to the eldest descendants of the male lineage from generation to generation, in accordance with the tradition observed in the worship of Mường ancestors. This allows NHÀ LANG to practically control three-quarters of the land, which is cultivated and maintained through periodic rotations of teams of village laborers, granting them the right to exploit the remaining quarter of the land as compensation. Despite these shortcomings, it cannot be denied that there is a fairly democratic relationship between NHÀ LANG and the Mường.

Compared to the feudal land system of Vietnam at that time, NHÀ LANG of the Mường has undeniable progressive factors because it defends not only its own rights but also those of the Mường. It must help the Mường villagers in cases of drought, famine, or poor harvests. It must be held accountable if its lang cun behaves in a manner unworthy of its rank. This is the case, for example, if the son of the latter commits a dishonorable act such as violating a village woman or getting into a fight in the street.

One can go as far as to depose the lang cun if he does not properly assume his authority and duties. In this case, the villagers can appeal to NHÀ LANG for his replacement. This also applies when the lang cun has no male heirs. It is also the responsibility of NHÀ LANG to organize the festivities related to the harvests and the feasts associated with the worship of the spirits. However, there are rules that the Mường villagers cannot ignore. They cannot marry a daughter of NHÀ LANG because she can only choose people of her rank and from NHÀ LANG. Similarly, a village woman who is randomly chosen as a wife by the lang cun and has children with him cannot claim to play an important role in NHÀ LANG. Her children cannot become lang cun because this position is reserved only for the eldest male descendants whose mother must be a daughter from NHÀ LANG. The members of NHÀ LANG are respected even if they are young. Regardless of the child’s age, a villager must respectfully address him as « Chàng » or « Nàng » when he is a boy or a girl from NHÀ LANG.

The hierarchy is so respected that it is possible to know the affiliation of the person in question. Moreover, this system allows the Lang Cun to have a monopoly on certain names (Ðinh, Hà, etc.). It was abolished in the 1950s by the Vietnamese government during the organization of agricultural cooperatives. Despite this, the system remains one of the original features of traditional Muong society and is one of the traditions that cannot be ignored when talking about the Muong. To refer to this system, the Muong habitually say: Mường có lang, làng có tạo. (Regions have lang just as villages have tạo (or Đạo in Vietnamese)). The term LANG ĐẠO is used to designate this system.

The Muong are accustomed to choosing lowlands and rugged terrain to build their houses. These are generally built against the slopes of hills and mountains to benefit from pure air and to facilitate movement for hunting and gathering. Each of these houses has a four-sided roof resembling a turtle shell. Their houses stand on very low stilts and are built on three levels. This corresponds well to the Muong conception of the creation of the universe: a celestial and terrestrial world (thiên giới và trần giới), a marine world (thủy quốc), and an underground world (âm phủ). The first level is reserved for food storage. It is, in a way, the granary.

The second level corresponds exactly to the place where family activities take place and where visitors are received. As for the last level located below the floor, it is intended for raising livestock and storing agricultural tools. The construction of their house must meet both material and spiritual requirements. For the Mường, the window of the room (voong tong) where the ancestor altar is located is very sacred. No one has the right to lean on this window or pass objects through it because, according to the Mường, the ancestors are not so separated from the living. They continue to participate with them in the major occasions of their existence. Furthermore, the two staircases of the house each have an odd number of steps. The main staircase, located very close to the entrance room (voong toong), is reserved exclusively for men. As for the women, they are obliged to take the second staircase, which is not far from their inner room (voong khua). The Mường improvise ingenious hydraulic systems (wheels, channels, etc.) to channel and raise water in order to irrigate the extraordinary terraced rice fields on the slopes of the hills. They also practice slash-and-burn agriculture, which provides them with benzoin, sugarcane, cassava, corn, etc.

Compared to other ethnic minorities, Mường costumes are quite unique. Men dress very simply. They wear indigo-colored pants. However, the clothing of Mường women is more complicated.

In general, the traditional costume of women includes: a white or blue turban (mu) made from a square piece of fabric measuring 35 cm x 150 cm, tied at the back of the neck; a camisole (yếm or ạo báng); a short shirt (áo cánh or ạo pắn in the Mường language); a long black skirt (váy or kloốc in the Mường language) reaching the ankle; and a wide belt made of silk or fabric.

The short Mường shirt, which is white, pale green, or pink, has four panels, with the two at the back sewn very well and the two at the front each having a long border running from the neck to the hem of the jacket. Similar to Vietnamese women, Mường women wear short shirts with a fairly round neckline measuring about 2.5 cm or 3 cm and two long sleeves. These shirts are open at the front and often unbuttoned; they are intended to cover the camisole, whose lower hem is neatly tucked behind the wide silk or coarse fabric belt of the skirt (cạp váy), vividly illustrating folkloric charm and seduction. This is the main distinctive feature that draws attention in Mường women’s costumes.

In the constitution of this wide belt, there are three rectangular bands with rich ornaments called respectively « dang trên, » « dang cao, » and « dang dưới, » which are sewn firmly together. The « dang dưới » band stands out from the other two by the richness of the motifs representing hieratic animals (dragons, phoenixes, turtles, etc.) or familiar ones (snakes, cranes, fish, etc.). The tunic (ạo chụng) is preferred over the jacket on festive days. The color of the outfit changes according to the status of the Mường woman. For her wedding, she must wear a long green tunic, while the white color is reserved for her maid of honor (dâu phụ). Funeral clothes (đồ tem) are always made inside out with frayed lower hems.

Among these, there is a mourning bonnet, a skirt without the wide multicolored rectangular belt, a short white shirt, and a belt made of rough fabric. In case of mourning for the in-laws, the Mường bride usually wears a black skirt, a camisole, a short shirt, and a red brocade jacket. The Mường have a saying: Diện như nàng dâu đi quạt (1) (Beautify oneself like the bride at the time of funerals). The outfit remains the same except that the short shirt must be white when the bride’s parents are still alive.

To show their differences from the Vietnamese, the Mường have a very well-known proverb:

Cơm đồ, nhà gác, nứớc vác, lợn thui, ngày lùi, tháng tới.

Steamed or simmered rice, stilt houses, water contained in bamboo tubes carried on the shoulder, spit-roasted pork, day behind and month ahead.

These are the characteristic customs of the Mường that are not found among today’s Vietnamese. The Mường prepare most foods and cakes from rice: glutinous rice (lõ kẳm) (2) and ordinary cooked rice (gạo tẻ). There are several types of cakes: rice cake (bánh chưng) during the Tết festivals, bánh bò or bánh trâu cakes in honor of the buffalo spirit (vía trâu), uôi cake for funerals, bắng cake for weddings, ống cake for engagements, etc.

For the calculation of days and months, the Mường rely on the Ðoi calendar, which is different from that of the Vietnamese. Ðoi is a star that moves faster than the moon. Based on the movement of this star, their Ðoi calendar is 4 months ahead of the Vietnamese lunar calendar.

Similar to the Vietnamese, the Mường have a communal house (đình) reserved for the tutelary spirit (or thành hoàng) in each hamlet or village. They believe in the existence of a large number of malevolent spirits that haunt the forests and that they call ma-khũ (or ma qũi in Vietnamese).These are disembodied souls wandering in the world of the dead and the living and can cause troubles for humans.

For the Mường, there are several souls within a human being that they call wại. These are divided into two categories: wại kang (the splendid souls) and wại thặng (the hard souls). The former are superior and immortal, while the latter, attached to the body, are evil. Death is only the consequence of the escape of these souls. Thanks to the funeral rite (ma chay), the superior souls can reside in the sky. They will need to be accompanied by the help and care of the family during their perilous migration. This is reflected in the affection and attachment that the Mường particularly reserve for the deceased through a set of rules regarding clothing, decoration, and accompaniment of the coffin (a split and hollowed-out wooden trunk). By performing the last rite, the souls will rest in peace; otherwise, the hard souls may become harmful and malevolent by turning into floating and dangerous spirits (Ma). This funeral rite (mo tang) can last several days (at least 12 days) and requires the presence of a sorcerer (or mo in the Mường language).

According to the Mường, the deceased possesses a supernatural force that prevents the living from communicating with them and helping them materially or spiritually. Only the thầy mo (or sorcerer) can do this. It is his responsibility to guide, before the burial, the soul of the deceased through all the administrative procedures with the celestial lord (Chạo Hẹ) to obtain a judgment. This will be delivered in a basket of ashes placed at the entrance of the house’s door, at the spot where the deceased is supposed to return home. There is a trial because during his life, the deceased sacrificed many animals for his consumption.

Depending on the verdict of the judgment revealed through the interpretation of signs or traces by the sorcerer, he may be condemned to reincarnate in the body of one of these sacrificed animals or henceforth lead a peaceful life. The sorcerer holds an important place in the Mường funeral rite. He is the one who accompanies the soul of the deceased to go collect money from the paternal grandfather’s house (ta keo heng), then borrow clothes from the house of Thiên mư, register in the ghost register (sổ ma) to facilitate movement, and finally provide essential everyday objects in the world of ghosts. He is also the one who gives the soul of the deceased the last meal and helps move their belongings into the tomb at night. There are a large number of objects: bowls, dishes, water jars, etc., and bronze drums for a lang cung (or feudal lord). Then it is up to the children of the deceased to organize, at the end of the third day of the funeral, a ceremony celebrating the return of his soul home before being able to begin his worship. This allows the deceased to be present from then on at all major occasions and at all feasts enlivening daily life: weddings, New Year celebrations, house inaugurations, etc. Similar to the Vietnamese, the Mường solemnly celebrate the anniversary of the death of the deceased and they wear mourning. The deceased is now part of the ancestors who have been honored on the family altar up to the fifth generation. Ancestor worship is very important in the spiritual life of the Mường.

Ma Chay

Similar to other ethnic minorities in Vietnam, the Mường are animists. They believe that everything has a soul. That is why their worship includes a large number of spirits, gods, and malevolent or benevolent spirits. Even in each Mường family, there is a benevolent spirit (or the ancestor demon (ma tổ tiên)) believed to protect the family. This is why there is a tradition that the Mường must observe after announcing the death of a loved one. The eldest son of the deceased must strike the door of the deceased’s house three times in a row with a knife to blame the family demon for not intervening in time during the father’s death. Before cutting down large trees in the forest, the Mường present an offering to the tree spirit (Thần cây) along with the axe that will be used for the work. Even when killing game during a hunt, they are obliged to pay homage to the predator spirit by offering the head and a shoulder once the animal is skinned. This is somewhat an honorable fine to the protector of predators, a custom frequently found among other hunting peoples. The Mường customarily venerate rocks, red pumpkins at the time of moving into a new house (lễ tân gia), the cây si tree, family totems, water sources, earth and kitchen spirits, etc.

Among the Mường, the resurrection and reincarnation of the soul are taboo subjects. For them, the soul is multiple, indestructible, and immortal, whether good or bad. In this Mường conception, the birth of a child is surrounded by mystery. They have asked many questions about its identity: child, spirit, malevolent spirit, or ancestral ghost?

Furthermore, for the Mường, the birth of the first child marks the beginning of maturity for young parents. They also rely on their children to have a peaceful retirement later on. The following Mường saying shows how much this support is desired:

Trẻ cậy cha, gìa cậy con

The young rely on their father just as the old rely on their children.

BIRTH

That is why the birth of a child holds an important place in the life of the Mường. To prepare for any eventuality, the Mường take a great number of usual and ritual precautions related to pregnancy and birth. When the mother is pregnant, she must follow certain immutable rules that have existed since time immemorial: protect herself against malevolent spirits with a leaf when passing in front of cemeteries and temples, avoid funerals (a harmful effect for the mother and her future child’s health), and weddings (a possible divorce for the parents),

refrain from walking on the bark of the tree used in the making of coffins (a possible miscarriage), do not flee in front of the snake to prevent the newborn from having an elongated tongue outside of its mouth, avoid eating « twin » fruits (a possible multiple birth), facilitate childbirth by waking up early in the morning and opening all the doors of the house, always maintain serenity and joy, avoid anger, etc.

Similarly, the husband must observe many prohibitions. He is forbidden to carry the coffin, to replace the roof of the house, and to renovate the house. As her childbirth approaches, the pregnant Muong woman has no interest in visiting her parents’ house because if the event occurs, she will be forced to give birth under the floor where the livestock are kept. According to the Muong, the pregnant woman is no longer part of their family (Con gái là con của người ta) but is the daughter of her husband’s family. The child born does not share the same blood as the family (khác máu tanh lỏng). This could later bring misfortune to the people of the house. For a girl who becomes pregnant without a husband, her delivery cannot take place in the house. It must be held in the garden. The punishment is the same for the girl who commits the fault of becoming pregnant before marriage.

In general, childbirth takes place at home. The happy event of the birth is announced by the presence of a distinctive sign always placed on the left (if it is a boy) and on the right (if it is a girl) at the entrance of the house. This sign will be removed at the end of the seventh day for a boy and the ninth day for a girl. Sometimes, the intervention of the sorcerer (thầy mo) is desirable in case it is believed that malevolent spirits are involved and held responsible for these difficulties.

There are many restrictions for the woman but also for the husband during the pregnancy. Even after birth, the child continues to be the cause of the greatest troubles for the parents during the first years of life. According to the Mường, the soul attached to its body is so fickle and wandering that it can escape from the body at any time. That is why the child, before leaving the house, needs to be protected by attaching a silver bracelet (pwok wai) to their wrists or ankles, which serves to prevent the soul from leaving. In case the soul leaves the body, this bracelet would allow it to return and take possession of the child. Moreover, to ensure that nothing happens to the child during the first years, the Mường parents organize a ritual ceremony known as cak wai to place the child under the protection of the protective spirits Mẹ Mụ.

These are, in a way, the celestial nurses of the child’s soul. The Mu have the right to have in each Mường house their altar, which is inaugurated after the first birth.

One cannot overlook the relationship between husband and wife among the Mường because it is one of the prominent traits that allows them to acquire commendable qualities and to establish a society that is peaceful, humanistic, hospitable, and altruistic.

Essentially based on fidelity, love, and happiness, this relationship helps to cement Mường society and enables it to better withstand the changes in customs that Vietnam has experienced since its reunification.

Despite the ease of being able to talk, meet, and get to know each other before marriage, young people cannot overstep the principles and demands that Mường tradition has established since time immemorial. A man must be serious, strong, upright, and kind. These are the qualities required of a man to be able to marry; otherwise, it is difficult for him to find a wife in Mường society. « Học ăn, học nói, học gói, học mở » (Learn to behave, to speak, to face, and to untie life’s difficulties) is the motto that one would like to apply in the search for a future husband for a Mường girl.

A man must know how to build the house, weave straw roofing panels, raise livestock, etc… It is also common to say in a Mường proverb: Một đàn ông không dựng nổi nhà (a man is incapable of building the house) to show how deeply they are attached to this preconceived notion. This requirement is easy to understand because in a harsh environment and in a society that is both supportive and hierarchical, a Mường man must demonstrate his ability and live up to this expectation. As for the Mường woman, she is not well off either. She is expected to possess certain qualities: to have good conduct, speak softly, be courteous, know how to make her own clothes, etc…

MARRIAGE

Haunted by the following proverb « Một đàn bà không cắt nổi gianh » (A woman is incapable of cutting the thatch), the Mường are led to have a clearer judgment about their future daughter-in-law and to discern her qualities and faults with lucidity. The motto « Lấy vợ xem tông, lấy chồng xem họ » (Marry a woman after observing her lineage, choose a husband after knowing his family) is also not foreign to their behavior and observation in marriage. To succeed in this, they need the help of a matchmaker (bà mờ) (1), who is in a way the central pivot in this difficult matter. She is not only the privileged interface between two families but also the responsible and committed witness of the transactions arising from these two families. She must be close to the future bride’s family. She must have talent in communication to convince people. The following Mường proverb: « Thiếu gì nước trong giếng, thiếu gì tiếng trong mồm mà không nói ra cho vừa lòng nhau » (There is so much water in the well, so many sounds in the mouth. Why can’t we find words to please each other?) shows the Mường’s strong attachment to communication.

His respect is unquestionable in the village. His profile meets many of the criteria required by Mường tradition: having an irreproachable life within his couple and family. It is obvious for her to have both a son and a daughter according to a Mường proverb: có nếp, có tẻ (there is sticky rice and ordinary rice). Before starting her approach with the woman’s family, she must consult the Đoi calendar (2) because, according to calculations, there are certainly harmful months and hours in the day (tháng thướm, giờ thướm) that must be avoided at all costs for the marriage. This is also the case for the Vietnamese with the « Ngâu » month, which they must prohibit for this event. She is supposed to know the birth date of each of the spouses to later avoid problems of incompatibility and discord in the couple. In case of divorce or failure, all grievances and reproaches from both sides will fall on her. Moreover, she will receive the blame from the local lord (quan lang).

After obtaining all the necessary information and the green light from the husband’s family, the matchmaker can begin to set the first meeting (Thoỏng thiếng or ướm tiếng) with the family of the future bride. She must inform all her relatives of this happy event and sometimes ask for their advice. During this visit, she usually gives the girl’s family a bottle of wine, which is immediately hung inside the house on the main pillar. If this bottle of wine is served after the meeting, the matchmaker will be sure of the success of her mission. Otherwise, she will leave with the bottle of wine. Known in Mường as « Tì kháo thiếng, » this step is followed at least 3 or 4 times by the back-and-forth (or nòm in Mường) of the matchmaker who does not immediately obtain agreement the first time. It is in the interest of the future bride’s family to show the matchmaker that this is an important matter requiring a period of reflection and consultation with the girl. This allows the relationship between the two families to deepen and become more intimate through the matchmaker.

Thanks to the back-and-forth exchanges (or nòm), it is ensured that the husband and wife possess all the required qualities. It is at the end of the last nòm that the date to celebrate the « nòm cả » (main nòm) will be chosen. Known as « ăn hỏi or tì nòm, » this ceremony is celebrated with great pomp. Among the gifts from the future husband, there are many symbolic items including a pig, 20 tubes of rice liquor (rượu cần), 2 pairs of sugarcane boots, betel leaves, plain sticky rice cakes (bánh chưng) without filling (không nhân), moral beauty, and a tacit agreement on the virginity of the future bride. All offered gifts must be in even numbers. It is during this ceremony that the future husband is introduced to the bride’s family. This introduction is known as mường: ti cháu (lễ ra mắt chú rể). At the end of this ceremony, the bride’s family will discuss the dowry with the future husband’s parents. Known in mường as « thách cưới (challenging the marriage), » it is easily accepted by the latter to show that they can meet this financial demand and to avoid losing face. It is the matchmaker’s responsibility to negotiate the dowry cost, reduce it, or outright refuse the marriage. Sometimes, the future husband is assured by the promise from the bride’s family of receiving a share of the inheritance in case she has no male heirs.

Known for her studies on the Mường, the French ethnologist Jeanne Cuisinier saw in this bargaining an act of purchase for the bride and groom. Nothing fully justifies this interpretation because on the daughter’s family’s side, there is indeed an act of commitment, a moral guarantee for this marriage with the participation of her entire lineage and a sincerity to want to perpetuate the couple’s life through this demanding financial requirement. In case of divorce, the wife’s family must return in full all the dowry received at the time of the marriage. This is an additional constraint that helps to avoid separation and to carefully consider before any irreversible act. It is also one of the factors that help explain the family and social cohesion of the Mường compared to other ethnic groups, particularly the Kinh. Moreover, for the future husband, there is a promise to grant him a share of the inheritance and a custom of adopting him into a family without male heirs. This is not really the meaning of the term « purchase » as found in its definition because the future husband will still receive a dowry in compensation.

According to Mường tradition, the official ceremony takes place three years after the main nòm. This is the period during which the future spouses should get to know each other, exchange conversations, and smooth out differences in order to facilitate their married life later on. This time, the ceremony starts very early in the morning because the matchmaker, accompanied by the groom’s relatives, must bring a large number of objects and animals that meet the requirements set at the time of the main nòm (a buffalo, two pigs, 5 or 6 baskets of sticky rice, a bunch of areca nuts, about a hundred betel leaves, 20 tubes of rice liquor, etc.). The number of people in the entourage must be even. Being received by the bride’s family and participating with others in a feast organized in their honor, the matchmaker will ask the bride’s parents for permission to bring their daughter to her husband’s house at a time deemed appropriate and lucky for the couple. Before leaving, the bride must pray in front of the ancestral altar and then perform lạy (a traditional Vietnamese gesture of respect) before her grandparents and parents. On the way back, she wears a conical hat and always carries a knife in her hand to ward off evil spirits and protect her « soul. » She is forbidden to turn her head backward. It takes time because, in most cases, the villages are very far from each other. That is why it is customary to say in Mường:Làm rể vào buổi trưa, làm dâu vào buổi tối. (One becomes the son-in-law in the morning, the daughter-in-law in the evening).

Once she arrives, she is welcomed by the husband’s sister, who asks her to wash her feet and step over a bundle of wood before climbing the house stairs. She is required to pray immediately in front of the kitchen spirit altar before performing the same gesture in front of the ancestors’ altar and the husband’s parents. Then a ritual ceremony (lễ tơ hồng) takes place in the middle of the house in the presence of the newlyweds. This will be followed by a feast in honor of the new couple. A few days later, the husband will return to the bride’s house for his first visit (lễ ra mặt). In the past, there was a period of challenge (bù mà ruộng) before they could truly begin their married life.

For the Vietnamese, the Mường are not only a minority ethnic group but also a people who preserve an original common culture. This is why it is in the interest of the Vietnamese to conduct ethnographic studies on the Mường, as through them, they have succeeded in better understanding the way of life of their ancestors as well as their archaic and millenary culture. The Vietnamese ethnologist Nguyễn Từ Chi had the opportunity to recall the characteristic traits of the Mường in Vietnamese culture in his book « The Mường Cosmology (Vũ trụ quan Mường). » Without the Mường, it is believed that Vietnamese culture is that of the Chinese, a widely false and erroneous opinion over the centuries. They deserve to always be the cousins of the Vietnamese or rather twin brothers, as they have often said in one of their popular songs:

Ta với mình tuy hai mà một

Mình với ta tuy một thành hai.

Mặc dù tôi và bạn là HAI bản thể, nhưng chúng ta là MỘT.

Là MỘT, tôi và bạn, chúng ta luôn có thể được coi là HAI.

Though you and I are TWO, we are ONE

Though I and you are ONE, we become TWO

Although you and I are TWO beings, we are but ONE.

Being ONE single being, you and I could always be considered as TWO.

The Mường are more than ever the survivors of the ancient culture of the Vietnamese. They are here to bear witness and to remind the Vietnamese that they, like them, have their own culture that allows them to distinguish themselves from the Chinese and that deserves to be known and preserved for future generations in the face of the rapid evolution of today’s Vietnamese society.

[Back to page « Vietnam, land of 54 ethnies »]

(1) Quạt: this word is used to refer to funerals (quạt ma).

(2) Glutinous rice is a type of rice whose grain is black.

(3) Sometimes it is a matchmaker (ồng mờ).

(4) Đoi calendar: a unique feature of Mường culture. This calendar consists of twelve bamboo pieces carved with lines to facilitate the indication of phenomena and climatic changes.

Bibliography

Người Mường ở Viet Nam. Editeur : Nhà Xuất Bản Thông Tấn. Hànôi.

Mosaïque culturelle du Vietnam. Nguyễn Văn Huy. Maison d’édition de l’éducation. 1997.

Bàn thêm về chế độ Nhà Lang trong xã hội Mường cổ truyền. Dưong Hà Hiếu.

Đám cưới truyền thống Mường. Phạm Lệ Hoa. Trường sư phạm nghệ thuật trung ương. National University of Art Education.

Rituels de naissance et liens de l’âme chez les Mường du Vietnam. Stéfane Boussat, Marcel Rufo.

À la recherche de l’origine de la langue vietnamienne. Nguyễn Văn Nhàn. Synergies riverains du Mékong. N° pp 35-44