Temple of littérature

One of the jewels in the heart of Hanoi

(Một bảo vật giữa lòng thủ đô)

Hiền tài là nguyên khí của quốc gia.

Nguyên khí thịnh thì thế nước mạnh.

Nguyên khí suy thì nước yếu

Talent is the life source of a nation.

A gushing source is the strength of a country.

A drying source weakens it.

The first National University of Vietnam, Quốc Tử Giám, celebrated its 940th anniversary in 2016. It can boast of having preceded by a good century the ancient and prestigious Western universities of Bologna, Oxford, and Paris. Built six years after the Văn Miếu, the Temple of Literature dedicated to Confucius, within the same enclosure, it is among the monuments of the capital that have survived ten centuries of turmoil, civil wars, and foreign invasions. It is contemporary with the Trấn Quốc, Một Cột, and Kim Lien pagodas. The imposing and well-preserved architectural complex in the heart of Hanoi contains very old parts that bear the color of time and the values of a past as rich as it is little known.

Consolidation of the Vietnamese nation

It was in 1076 that the College of the Sons of the Nation, Quốc Tử Giám, was created by King Lý Nhân Tông, of the great Later Lý dynasty. Since the reconquest of independence in 939, the task facing the Vietnamese sovereigns was immense and arduous. The previous dynasties of Ngô, Ðinh, and Earlier Lê had exhausted themselves in internal divisions and wars of conquest at the beginning of the victorious march southward. At the beginning of the 11th century, Vietnam, then renamed Đại Việt, was a nation of original ancient culture in a young state.

Inside still poorly established borders in the South, it remained necessary to strengthen national unity and to overcome the rivalries of great families that threatened to tear the country apart. Outside, it was necessary to maintain good vassal relations with the powerful Chinese neighbor. The Lý showed themselves capable of meeting these challenges. The construction of dikes to address the flooding of the Red River allowed the population to settle and favored the growth of agriculture.

The buying and selling of land were regulated, which led to the emergence of a class of small landowners alongside the great feudal lords. Crafts developed (weaving, goldsmithing, pottery, porcelain), and consequently, trade. On the advice of competent Confucian administrators, the Lý managed to establish a strong centralized government and were able to give legitimacy to the ruling elite. Inspired by the Chinese administrative model, King Lý Nhân Tông organized in 1075 the first examination to recruit mandarins who would exercise power. The following year, he added to the Văn Miếu a higher school to train senior officials, the Quốc Tử Giám. The educational institution, in this tolerant country, existed peacefully right next to the place of worship. Combining a temple dedicated to Confucius and a place of learning into a single complex, this construction is a unique work that highlights the originality of Vietnam compared to China.

Rise of a National Culture

During almost ten centuries of Chinese colonization, the Vietnamese had preserved their cultural originality and assimilated a large part of Chinese culture. The College of the Sons of the Nation therefore spread Confucian humanities: Confucian classics, philosophy, literature, history, and politics. Brilliant candidates memorized the Four Books of Confucianism, but also the history of Vietnam and China. They also studied the rules of poetic composition, learning to prepare all sorts of documents: royal edicts, speeches, mission reports, analyses, essays. The language in use was certainly Chinese or hán; however, the Vietnamese very early on, probably from the 12th century, used a special iconographic script, nôm, to transcribe the popular national language, kinh.

Under Chinese rule, the Vietnamese had learned just what was necessary to become good servants. Until the tenth century, there is no trace of Vietnamese literature. Only legends may have crystallized the collective memory, prevented from freely expressing itself under the pressure of the occupier. The nôm script, derived from Chinese ideographic writing, represented a national and popular reaction to foreign cultural domination. « The soul of a people lives in its language, » said Goethe.

This is an obvious fact in Vietnam. The language transcribed in nôm experienced vigorous growth whenever the national and popular movement gained momentum. After the great Nguyễn Trãi in the 14th century wrote his poems in nôm, the demotic script gained its nobility and no scholar disdained writing in nôm. Another great Vietnamese figure, Nguyễn Huệ, carried out a true revolution by imposing nôm as the official language in administration and mandarin examinations during his reign at the end of the 18th century.

The royal examinations gave a decisive boost to education throughout the country. The National University became for a long time the keystone of the educational system. Schools were established to prepare candidates for the mandarin examinations.

Alongside the large feudal estates existed a well-organized system of rural communes. In many of them, there was a private school alongside public schools, both at the national, provincial, and local levels. The teachers were educated men who had failed the exams, or holders of a baccalaureate, a license, and doctoral laureates who did not want to become mandarins or who were disillusioned with politics. The prestige of knowledge, the respect for teachers and talent had spread over the centuries even into the poorest peasantry.

Which mother did not dream of seeing her sons one day take the difficult exams? The popular saying was deeply ingrained in people’s minds: « Without a teacher, I challenge you to achieve anything. » Literature and public service were not separate in the traditional Vietnamese educational system. Poets contributed to the economic life of their country. Among the most brilliant statesmen and strategists, many were poets. The most famous among them, revered as heroes by the entire population, were:

Trần Hưng Đạo (1213-1300), who triumphed over the Mongols by defeating Kublai Khan

Nguyễn Trãi (1380–1442), a great poet and statesman who ended a new Chinese occupation by the Ming.

Nguyễn Du, a diplomat under the Lê dynasty, who with his verse novel, the Kiều, brought the nôm script to perfection. The latter two are listed by UNESCO in the Pantheon of the Men of Culture of Humanity.

The obstacle-filled journey of a candidate for the royal exams.

Initially, the national exams were held irregularly, depending on the needs of the imperial administration. From 1434 until 1919, the date of the last session, they took place every three years.

When King Lê Thần Tông redefined the rules in the 14th century, the examination took place in two successive levels: regional, then national, each in four phases that could last several months in total. It was necessary to successfully pass each stage in order to qualify for the next. The final test was held at the imperial palace before the king, who personally examined the last group of future doctors.

Some figures provide an eloquent overview of the demands and importance of the royal competitions:

On average, 70,000 to 80,000 candidates competed in the regional competitions.

Between 450 and 6,000 candidates were selected from these to take part in the national exam in Hanoi. They settled for the duration of the tests on the university campus in the city center with their bamboo beds, brushes, and inkwells. In 1777, the National University and the Doctoral Quarter had become an impressive institution comprising 300 classrooms, a huge library, and a publishing house. This vast complex was destroyed by war in 1946. At the end of the final exam at the imperial palace, only 15 candidates were awarded the title of Doctor (tiến sĩ), with an average age of 32. Between 1076 and 1779, the date of the last session held in Thăng Long (Hanoi), 2,313 candidates received the title of Doctor.

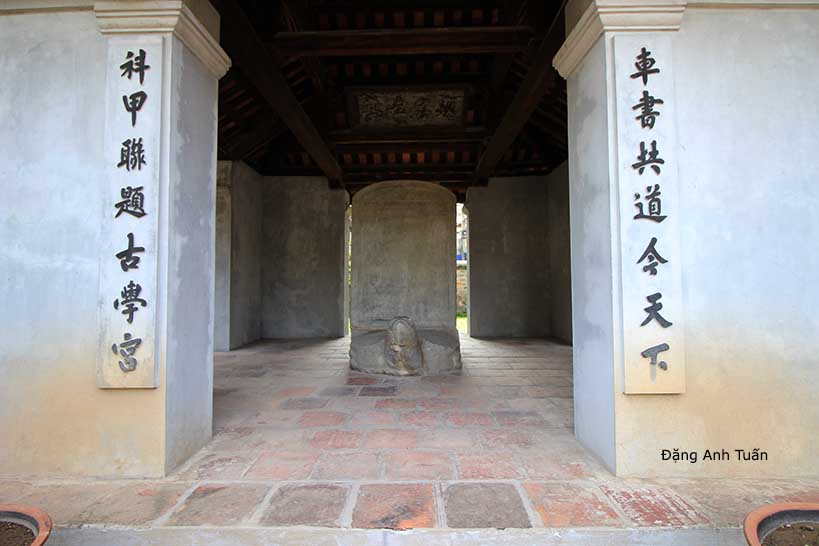

1306 of them have their names and ranks engraved in Chinese characters on the 82 steles (41 on each side) in the third space of the Văn Miếu Quốc Tự Giám in Hanoi. These 82 steles preserve the memory of the laureates admitted between 1442 and 1779. It was King Lê Thánh Tông who took the initiative to pay tribute in this way to the great servants of the country. 116 national exams took place during this period, which means that 34 steles are missing, and the reasons why they were not erected or have disappeared are unknown. From 1802, with the reign of Gia Long, the triennial exams were held in Hué until their abolition in 1919. The Quốc Tự Giám became once again the Văn Miếu, Temple of Literature, but was preserved. The tradition of inscribing the Doctors of the Nation on the honor roll was also maintained.

In the Forbidden City of Hué, on the first floor of the Ngọ Môn Gate, their names are clearly mentioned on a large black marble tablet, along with their village and province of origin. The competency exams were coupled with a formidable physical challenge for those from the provinces. The journey to the capital was fraught with dangers. Coming from a distant province, the future graduates sometimes had to travel up to 300 km or more, bringing with them food, a tent, a narrow bamboo bed, and writing materials.

Along the way, they had to fear both highway bandits and attacks from tigers and snake bites. If they managed to overcome all these obstacles, most of them preferred to stay a few years on site to study, in order to ensure the best chances of success.

Popular imagery often depicted the triumphant return of doctors to their native village, announced by a procession of banners and pennants, palanquins, ceremonial objects, preceded by family and friends. Throughout the journey, drums sounded marking the arrival of the child of the country who brought back, along with the doctoral certificate issued by the king, glory to the entire village. The village was henceforth distinguished as « a land of literature (đất văn chương). »

Then the laureate did not fail to bow before the altar of the ancestors and Confucius, before inviting everyone to a sometimes ruinous banquet. During the second millennium B.C. of Vietnam’s history, the intellectual elite emerging from national competitions produced, alongside brilliant strategists, mathematicians, statesmen, philosophers, men of letters, its share of simple bureaucrats and corrupt mandarins. According to Confucian tradition, no woman had access to official education.

The patients were so numerous that Phú Doãn Hospital (the current German-Vietnamese hospital) was soon overwhelmed. It was set up within the grounds of the Văn Miếu Quốc Tử Giám, whose ramparts served as a barrier against contagion. The disease was brought under control thanks to a vaccine developed by Doctor Yersin and the dedication of the doctors. But the Temple was in such a state that the French authorities decided to transform it into a hospital. They began searching for a new location to build the new building.

Aware that he was attacking the Holy See of Vietnamese culture, the representative of the Governor-General of Indochina, Pasquier, first consulted a prominent scholar, and the latter’s conclusion was unequivocal: « Adverse circumstances have soiled the steles and make the people’s hearts bleed. The Nguyễn, by transferring the capital to Huế, respected the integrity of the Temple. If you want to move it, the population will revolt. » A few days later, the French Government allocated a sum of 20,000 piastres to restore the Temple to its original state.

At other times in its troubled history, the population of Hanoi had shown its attachment to this monument, a symbol of its intellectual curiosity, passion for study, and creativity, notably during the fratricidal wars between the Trịnh and the Nguyễn. Nevertheless, in its current state, the Temple of Literature occupies a smaller space than at its peak.

Toàn cảnh nội văn từ

Thử địa vi thủ, thiên thu cần tạo thương lưu phương

Overview of the literary content

Trying the geographical hand, a thousand years need to create a lasting fragrance

Of all the temples dedicated to literature, this one is the high place;

the scent of culture lingers there beyond millennia.

The Temple of Literature (Văn Miếu)

Chu Văn An

Ông tổ của các nhà nho nước Việt

Erection of the laureates’ steles