On est habitué à dire en vietnamien : sống chết đều có số cả (Chacun a son jour J pour la vie comme pour la mort).

Ði buôn có số, ăn cỗ có phần (On a sa vocation au commerce comme on a sa part au festin). Dans la vie courante, chacun a sa taille pour ses vêtements et pour ses chaussures. On s’aperçoit que contrairement aux Chinois qui adorent les nombres pairs, les Vietnamiens privilégient plutôt les nombres impairs (sô’ dương) que les nombres pairs (sô’ âm).

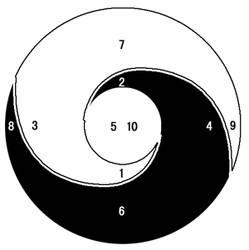

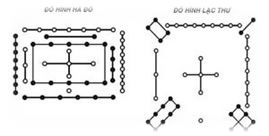

On trouve l’utilisation fréquente des nombres impairs dans les locutions vietnamiennes : ba mặt một lời ( On a besoin d’être face à face en présence d’un témoin), ba hồn bảy vía ( trois âmes et 7 supports vitaux pour les hommes càd on est paniqué), Ba chìm bảy nổi chín lênh đênh ( très mouvementé), năm thê bảy thiếp ( avoir 5 épouses et 7 concubines càd avoir plusieurs femmes ), năm lần bảy lượt (plusieurs fois), năm cha ba mẹ ( hétéroclite), ba chóp bảy nhoáng (avec précipitation et sans soin ), Môt lời nói dối , sám hối 7 ngày (Une parole mensongère équivaut à sept jours de repentance), Một câu nhịn chín câu lành (Eviter une phrase vexante c’est avoir 9 phrases aimables) etc … ou celle des entiers multiples du nombre 9 : 18 (9×2) đời Hùng Vương ( 18 rois légendaires Hùng Vương ), 27 (9×3) đại tang 3 năm (27 tháng)(ou un deuil porté sur trois ans qui se traduit en fait par 27 mois seulement), 36 (9×4) phố phường Hànội (Hànội avec 36 quartiers ) etc.. On n’oublie pas de citer non plus les chiffres 5 et 9 ayant chacun un rôle très important. Le chiffre 5 est le chiffre le plus mystérieux car tout commence à partir de ce nombre. Le Ciel et la Terre ont les 5 éléments ou agents (Ngũ hành) donnant naissance aux mille choses et êtres. Il est placé au centre du Plan du Fleuve et de l’Ecrit de la rivière Luo qui sont à la base de la mutation des 5 éléments (Thủy, Hỏa, Mộc, Kim, Thổ)( Eau, Feu, Bois, Métal et Terre).

Il est associé à l’élément Terre dans la position centrale dont le paysan a besoin pour permettre de connaître la direction des points cardinaux. Cela revient ainsi à l’homme le centre dans la gestion des choses et des espèces et des quatre cardinaux. C’est pour cette raison que dans la société féodale, cette place est réservée au roi car c’est lui qui a gouverné les gens. En conséquence, le chiffre 5 lui appartenait ainsi que la couleur jaune symbolisant la Terre. Cela explique la couleur qu’ont choisie les empereurs vietnamiens et chinois pour leurs habits.

Ho Tou Lo Chou

(Hà Đồ Lạc Thư)

Outre le centre occupé par l’homme, un animal symbolique est associé à chacun des quatre points cardinaux: le Nord par la tortue, le Sud par le phénix, l’Est par le tigre et l’Ouest par le dragon. Rien n’est étonnant de trouver au moins dans cette attribution les trois animaux vivant dans une région où la vie agricole joue un rôle considérable et l’eau est vitale. C’est le territoire des Bai Yue. Même un dragon si méchant dans d’autres cultures devient un animal gentil et noble imaginé par les peuples pacifiques des Bai Yue. Le chiffre 5 est connu encore sous le nom « Tham Thiên Lưỡng Đia » (ou ba Trời hai Ðất ou 3 Yang 2 Yin) dans la théorie du Yin et du Yang car l’obtention du nombre 5 provenant de l’assemblage des chiffres 3 et 2 correspond mieux au pourcentage raisonnable du Yin et du Yang que celle résultant de l’assemblage des chiffres 4 et 1.

Dans ce dernier, on s’aperçoit que le nombre Yang 1 est dominé beaucoup par le nombre Yin 4. Ce n’est pas le cas de l’assemblage des nombres 3 et 2 où le nombre Yang 3 domine légèrement le nombre (Yin) 2. Cela favorise le développement de l’univers dans une harmonie presque parfaite. Autrefois, le cinquième jour, le quatorzième jour (1+4=5) et le vingt-troisième jour (2+3=5) du mois étaient réservés pour la sortie du roi. Il était interdit aux sujets de faire le commerce durant son déplacement et de troubler sa promenade. C’est peut-être la raison qui explique qu’un grand nombre de Vietnamiens d’aujourd’hui, influencés par cette tradition ancestrale continuent à ne pas choisir ces jours pour la construction des maisons, pour le voyage et pour les achats importants.On est habitué à dire en vietnamien :

Chớ đi ngày bảy chớ về ngày ba

Mồng năm, mười bốn hai ba

Đi chơi cũng lỗ nữa là đi buôn

Mồng năm mười bốn hai ba

Trồng cây cây đỗ, làm nhà nhà xiêu

Il faut éviter de partir le 7ème jour et de rentrer le 3ème jour du mois. Pour le 5ème, le 14ème et le 23ème jour du mois, vous seriez perdant si vous faites une sortie ou le commerce. De même vous verriez la chute de l’arbre ou l’inclinaison de votre maison si vous le plantez ou vous la construisez.

Le chiffre 5 est cité fréquemment dans l’art culinaire vietnamien. La sauce la plus typique des Vietnamiens reste la saumure de poisson. Dans la préparation de cette sauce nationale, on note la présence de 5 saveurs classées selon les 5 éléments du Yin et du Yang: mặn ( salée ) avec le jus de poisson (nước mắm), đắng (amère) avec le zeste du citron (vỏ chanh), chua (acide) avec le jus du citron (ou du vinaigre), cay (piquante) avec les piments pilés en poudre ou coupés en miettes et ngọt (sucrée) avec du sucre en poudre. Ces cinq saveurs ( mặn, đắng, chua, cay, ngọt ) combinées et trouvées dans la sauce nationale des Vietnamiens correspondent respectivement aux 5 éléments définis dans la théorie de Yin et de Yang (Thủy, Hỏa , Mộc , Kim Thổ)(Eau, Feu , Bois, Métal et Terre ).

De même, on retrouve ces 5 saveurs dans le potage aigre-doux (canh chua) préparé avec du poisson: acide avec les graines de tamarin ou avec le vinaigre, sucré avec les tranches d’ananas, piquant avec les piments coupés en lamelles, salé avec le jus de poisson et amère avec quelques gombos (đậu bắp) ou avec les fleurs de fayotier (bông so đũa). Au moment où ce potage est servi, on lui ajoutera quelques herbes parfumées comme le panicaut (ngò gai), rau om (herbe ayant la flaveur proche de la coriandre avec une note citronnée en plus). C’est un trait caractéristique du potage aigre-doux du Sud-Vietnam et différent de ceux trouvés dans les autres régions du Vietnam.

On ne peut pas oublier de citer le gâteau de riz gluant que les Proto-Vietnamiens avaient réussi à léguer à leurs descendants au fil des millénaires de leur civilisation. Ce gâteau est la preuve intangible de l’appartenance de la théorie du Yin et du Yang et de ses cinq éléments aux Cent Yue dont les Proto-Vietnamiens faisaient partie car on retrouve dans la confection de ce gâteau le cycle d’engendrement de ces 5 éléments.

(Feu->Terre->Métal->Eau->Bois)

A l’intérieur du gâteau, on trouve un morceau de viande de porc de couleur rouge (le Feu) entouré par une sorte de pâte faite avec des fèves de couleur jaune (la Terre). Le tout est enveloppé par le riz gluant de couleur blanche (le Métal) pour être cuit avec de l’eau bouillante (l’Eau) avant de trouver une coloration verte sur sa surface grâce aux feuilles de latanier (le Bois).

Il y a un autre gâteau qui ne peut pas être manquant dans les mariages. C’est le gâteau susê ou phu-Thê (mari-femme) ayant la forme ronde à l’intérieur et enveloppé par des feuilles de bananier (couleur verte) en vue de lui donner l’apparence d’un cube ficelé avec un ruban de couleur rouge. Le cercle est placé ainsi à l’intérieur du carré (Dương trong âm)(Yang dans Yin). Ce gâteau est composé de la farine du tapioca, parfumé au pandan et parsemé de graines de sésame (vừng đen) de couleur noire. Au cœur de ce gâteau se trouve une pâte faite avec des haricots de soja cuits à la vapeur (couleur jaune), de la confiture des graines de lotus et de la noix de coco râpée (couleur blanche). Cette pâte ressemble énormément à la frangipane trouvée dans les galettes des rois. Sa texture collante rappelle le lien fort qu’on veut représenter dans l’union. Ce gâteau est le symbole de la perfection de l’amour conjugal et de la loyauté en accord parfait avec le Ciel et la Terre et les 5 éléments symbolisés par les cinq couleurs (rouge, verte, noire, jaune et blanche).

Ce gâteau est relaté par le conte suivant : autrefois, il y avait un commerçant s’adonnant aux débauches et ne pensant pas à retourner à la famille bien qu’avant son départ, sa femme lui donnât le gâteau susê et promît de rester chaleureuse et doucereuse comme le gâteau. C’est pourquoi ayant appris cette nouvelle, sa femme lui envoya d’autres gâteaux phu thê accompagnés par les deux vers suivants :

Từ ngày chàng bước xuống ghe

Sóng bao nhiêu đợt bánh phu thê rầu bấy nhiêu

Depuis ton départ, autant des vagues étaient rencontrées par ton embarcation, autant d’afflictions étaient connues par le gâteau susê.

Lầu Ngũ Phụng

Dans l’architecture, le chiffre 5 n’est pas oublié non plus. C’est le cas de la porte méridienne de la citadelle de Huế qui est un puissant massif en maçonnerie percé de cinq passages et surmonté d’une élégante structure de bois à deux niveaux, le Belvédère des Cinq Phénix (Lầu Ngũ Phụng).

Vu dans l’ensemble, celui-ci ressemble à un groupement de 5 phénix juchés intimement avec leurs ailes déployées. Ce belvédère possède cent colonnes en bois de fer et peintes en rouge permettant de supporter ses neuf toitures. Ce chiffre 100 a été bien examiné par les spécialistes vietnamiens. Pour l’archéologue renommé Phan Thuận An, il correspond exactement au nombre total obtenu par l’addition des deux nombres trouvés respectivement dans le plan du Fleuve (Hà Ðồ) et l’Ecrit de la rivière Luo (Lạc thư cửu tinh đồ) et symbolisant ainsi l’harmonie parfaite de l’union du Yin et du Yang. Ce n’est pas l’avis d’un autre spécialiste Liễu Thượng Văn. Selon ce dernier, cela représente la force de 100 familles ou du peuple (bách tính) et reflète bien la notion dân vi bản (prendre le peuple comme base) dans la gouvernance de la dynastie des Nguyễn. La toiture du pavillon central est couverte de tuiles jaunes « lưu ly », les autres de tuiles bleues « lưu ly ». La porte principale, juste au milieu, c’est la porte méridienne (Ngọ Môn) pavée de pierres « Thanh » teintées en jaune, et consacrée au passage du roi. Des deux côtés, on trouve la porte de Gauche et la porte de Droite (Tả, Hữu, Giáp Môn) réservées aux mandarins civils et militaires. Puis les deux autres portes latérales Tả Dịch Môn và Hữu Dịch Môn sont prévues pour les soldats et les chevaux. C’est pourquoi on est habitué à dire en vietnamien :

Ngọ Môn năm cửa chín lầu

Một lầu vàng, tám lầu xanh, ba cửa thẳng, hai cửa quanh

La porte méridienne possède 5 passages et neuf toitures dont l’une est vernissée en jaune et les 8 huit autres en vert. Il y a trois portes principales et deux latérales.

A l’est et à l’ouest de la citadelle, on trouve la Porte de l’Humanité et la Porte de la Vertu qui sont réservées respectivement pour les hommes et les femmes.

Le chiffre 9 est un nombre Yang (ou impair). Il représente la puissance du yang à son maximum et il est difficile de l’atteindre. C’est pourquoi autrefois l’empereur s’en servit souvent pour montrer sa puissance et sa suprématie. Il monta les neuf marches symbolisant l’ascension de la montagne sacrée où se trouvait son trône. Selon l’on-dit, la cité interdite de Huế comme celle de Pékin possédait 9999 pièces. Il est utile de rappeler que la cité interdite de Pékin a été supervisée par un Vietnamien de nom Nguyễn An exilé très jeune à l’époque des Ming. L’empereur comme chacun de ses palais, est tourné face au sud, à l’énergie Yang, afin que l’empereur reçoive le souffle vital du soleil car il est le fils du Ciel. Au Vietnam, on trouve les neuf urnes dynastiques de la citadelle de Huê, les neuf branches du fleuve Mékong, les neuf toitures du belvédère des Cinq Phénix etc…Dans le conte intitulé « Le génie des Montagnes et le génie des Fleuves (Sơn Tinh Thủy Tinh) », le dix-huitième (2×9) roi Hùng Vương proposa pour la dot du mariage de sa fille Mị Nương: un éléphant à 9 défenses, un coq à 9 ergots et un cheval à 9 crinières rouges. Le chiffre 9 symbolise le Ciel dont la date de naissance est le neuvième jour du mois Février.

Moins importants que les chiffres 5 et 9, le chiffre 3 (ou Ba ou Tam en vietnamien) est lié étroitement à la vie quotidienne des Vietnamiens. Ceux-ci n’hésitent pas à l’évoquer dans un grand nombre d’expressions populaires. Pour signifier une certaine limite, un certain degré, ils ont l’habitude de dire:

Không ai giàu ba họ, không ai khó ba đời:

Nul ne peut prétendre s’enrichir jusqu’aux trois générations comme nul n’est exigeant jusqu’aux trois vies successives.

Il arrive souvent aux Vietnamiens de ne pas accomplir une certaine chose en une seule fois, ce qui les oblige d’effectuer l’opération jusqu’à trois fois. C’est l’expression suivante qu’ils emploient fréquemment: Nhất quá Tam. C’est le chiffre trois, une limite qu’ils ne souhaitent pas outrepasser dans l’accomplissement de cette tâche. Pour dire que quelqu’un est irresponsable, ils le désignent sous le vocable « Ba trợn« . Celui qui est opportuniste est appelé Ba phải. L’expression » Ba đá » est réservée aux gens vulgaires tandis que ceux qui ne cessent pas de s’enchevêtrer dans de petites affaires ou des ennuis interminables reçoivent le titre » Ba lăng nhăng« . Pour soupeser ses paroles, le Vietnamien a besoin de plier les trois pouces de sa langue. ( Uốn Ba tấc lưỡi ) .

Le chiffre Trois est synonyme aussi de quelque chose d’insignifiant et sans importance. C’est ce qu’on trouve dans les expressions populaires suivantes:

Ăn sơ sài ba hột: Manger peu. (Manger simplement trois grains).

Ăn ba miếng: idem

Sách ba xu: Bouquin sans valeur. (le bouquin ne valant que trois sous).

Ba món ăn chơi: Quelques plats à goûter. (Trois plats pour se divertir)

Analogue au chiffre 3, le chiffre 7 est cité souvent dans la littérature vietnamienne. On ne peut pas ignorer non plus l’expression Bảy nỗi ba chìm với nước non (Je surnage 7 fois et je sombre trois fois si on la traduit textuellement) que la poétesse Hồ Xuân Hương a employée et immortalisée dans son poème intitulé « Bánh trôi nước » :

Thân em vừa trắng lại vừa tròn

Bây nỗi ba chìm với nước non

……….

pour décrire les difficultés rencontrées par la femme vietnamienne dans une société féodale et confucéenne. Celle-ci n’épargnait pas non plus ceux qui avaient un esprit d’indépendance, de liberté et de justice. C’est le cas du lettré engagé Cao Bá Quát dégoûté de la scolastique de son époque et rêvant de remplacer la monarchie autoritaire des Nguyễn par une monarchie éclairée. Taxé d’être l’auteur de l’insurrection des Sauterelles (Giặc Châu Chấu) en 1854, il fut condamné à mort et n’hésita pas à donner jusqu’à avant son exécution, sa réflexion sur le sort réservé à ceux qui osaient critiquer le despotisme et la société féodale dans son poème :

Ba hồi trống giục đù cha kiếp

Một nhát gươm đưa, đéo mẹ đời.

Trois coups de gong sont pour ce sort misérable

Une tranche de sabre achève cette vie de chien.

Si la théorie du Yin et du Yang continue à hanter leur esprit pour son caractère mystique et impénétrable, elle reste néanmoins un mode de pensée et de vie auquel un bon nombre des Vietnamiens ne renoncent pas à se référer quotidiennement pour les pratiques courantes et le respect des us et des traditions ancestrales.

Bibliographie

-Xu Zhao Long : Chôkô bunmei no hakken, Chûgoku kodai no nazo in semaru (Découverte de la civilisation du Yanzi. A la recherche des mystères de l’antiquité chinoise, Tokyo, Kadokawa-shoten 1998).

-Yasuda Yoshinori : Taiga bunmei no tanjô, Chôkô bunmei no tankyû (Naissance des civilisations des grands fleuves. Recherche sur la civilisation du Yanzi), Tôkyô, Kadokawa-shoten, 2000).

-Richard Wilhelm : Histoire de la civilisation chinoise 1931

-Nguyên Nguyên: Thử đọc lại truyền thuyết Hùng Vương

– Léonard Rousseau: La première conquête chinoise des pays annamites (IIIe siècle avant notre ère). BEFO, année 1923, Vol 23, no 1

-Paul Pozner : Le problème des chroniques vietnamiennes., origines et influences étrangères. BEFO, année 1980, vol 67, no 67, p 275-302

-Dich Quốc Tã : Văn Học sữ Trung Quốc, traduit en vietnamien par Hoàng Minh Ðức 1975.

-Norman Jerry- Mei tsulin (1976) : The Austro asiatic in south China : some lexical evidence, Monumenta Serica 32 :274-301

-Henri Maspero : Chine Antique : 1927.

-Jacques Lemoine : Mythes d’origine, mythes d’identification. L’homme 101, paris, 1987 XXVII pp 58-85

-Fung Yu Lan: A History of Chinese Philosophy ( traduction vietnamienne Đại cương triết học sử Trung Quốc” (SG, 1968).68, tr. 140-151)).

-Alain Thote: Origine et premiers développements de l’épée en Chine.

-Cung Ðình Thanh: Trống đồng Ðồng Sơn : Sự tranh luận về chủ quyền trống

đồng giữa h ọc giã Việt và Hoa.Tập San Tư Tưởng Tháng 3 năm 2002 số 18.

-Brigitte Baptandier : En guise d’introduction. Chine et anthropologie. Ateliers 24 (2001). Journée d’étude de l’APRAS sur les ethnologies régionales à Paris en 1993.

-Nguyễn Từ Thức : Tãn Mạn về Âm Dương, chẳn lẻ (www.anviettoancau.net)

-Trần Ngọc Thêm: Tìm về bản sắc văn hóa Việt-Nam. NXB : Tp Hồ Chí Minh Tp HCM 2001.

-Nguyễn Xuân Quang: Bản sắc văn hóa việt qua ngôn ngữ việt (www.dunglac.org)

-Georges Condominas : La guérilla viêt. Trait culturel majeur et pérenne de l’espace social vietnamien, L’Homme 2002/4, N° 164, p. 17-36.

-Louis Bezacier: Sur la datation d’une représentation primitive de la charrue. (BEFO, année 1967, volume 53, pages 551-556)

-Ballinger S.W. & all: Southeast Asian mitochondrial DNA Analysis reveals genetic continuity of ancient Mongoloid migration, Genetics 1992 vol 130 p.139-152….