French version

French version

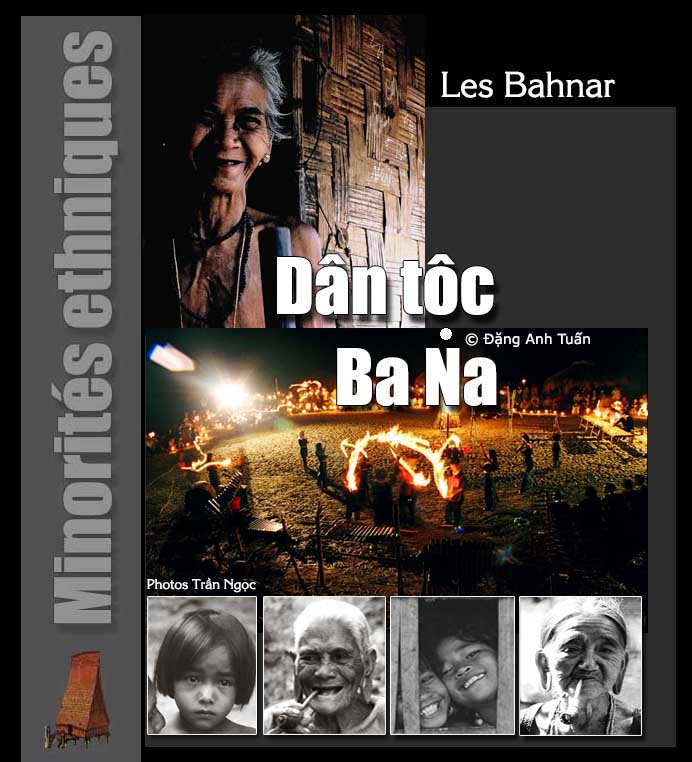

Vietnamese version

First part

The Bahnar are part of the Mon-Khmer group of the Austro-Asiatic ethnolinguistic family. They live clustered in the northern part of the Central Highlands of Vietnam (Kontum, Gia Lai, Bình Định, etc.), away from the people of the plains who, at one time, still treated them as savages (or Mọi in Vietnamese). This is due to a lack of understanding of their culture, which leads to maintaining this deplorable attitude and grotesque vision. Even French explorers did not stop referring to them as Mọi in their exploration accounts during the colonial period.

Only ethnologists like the late Georges Condominas succeeded in recognizing them as people respectful of nature and the environment, people deeply connected in harmony with the environment where they live and where all beings (plants and animals), mountains and waters, have a soul like them. The Bahnar live in mountainous regions at various altitudes. They grow rice in dry fields or on swidden fields (slash-and-burn). These often require the relocation of plantations and villages because the ashes from the clearing do not allow the soil to remain fertile beyond two or three years due to the rain washing them away during its passage. The harvests are abundant in the first year after the burning.

The second year begins to be less good. Under poor conditions, it is impossible to keep the field beyond two years. That is why the Bahnar tend to use dry fields, which are often arranged along the edges of waterways. The hoe is the main tool used in their agriculture, but since the beginning of the 20th century, the use of the plow in flooded rice fields has become increasingly common.

Their religious beliefs and myths are similar to those of other ethnic groups encountered in Vietnam. Animists, the Bahnar worship plants such as banyan trees and ficus. The kapok tree is considered the guardian and serves as the sacrificial pole in the celebration of rites and ceremonies. Every river, every water source, every mountain, or every forest has its own spirit (or iang). The Bahnar divide the spirits into two categories: higher-ranking spirits and lower-ranking spirits. The former are gods who created the world and watch over human activities. Among these gods are Bok Kơi Dơi (Male Principle of Nature), Iă Kon Keh (Female Principle of Nature), Bok Glaih (God of thunder and lightning), Iang Xơri (Spirit of rice), Iang Dak (Spirit of waters), etc. As for the second category, most of the spirits are spirits of animals, trees, or objects, including Bok Kla (Mr. Tiger), Roih (Elephant), Kit drok (Toad), Iang Long (Tree spirit), Iang Xatok (Jar spirit), etc.

Faced with these religious beliefs and superstitions, Catholic missionaries struggled at the beginning of their mission to convert the Bahnar to Christianity. They were even forced to falsify their myths to corroborate the Bible. The Christian Bahnar were so attached to their animist beliefs that they gradually managed to assimilate Christianity over the years.

For the Bahnar, death is not the end of a life but the beginning of another in the afterlife. The soul, which the Bahnar call pơngơl, transforms into a ghost (or atâu in Bahnar) and joins the ancestors in the spirit world (dêh atâu). The Bahnar believe that a human being consists of a body (akao) and the soul pơngơl. Life is only possible thanks to the soul and not the body. But the soul is invisible to humans. Only the shaman can see it in the form of a spider, a cricket, or a grasshopper. Each human has three souls: one important main soul (pơngơl xok ueh) which must be attached to the top of the head, and two complementary souls (pơngơl kơpal kol and pơngơl hadang), one located on the forehead and the other in the body. If the main soul, which constitutes the essential breath for the person, leaves the body for an unknown reason and does not return, the person will become ill and die. The complementary souls are there to temporarily replace the main soul. It is the main soul that metamorphoses into a ghost in the other world. This spirit (or ghost) needs food, clothing, and even a house to protect itself from rain and sun. This is the animist belief that the deceased continues to have the same needs in the afterlife. It is also for this reason that during the burial of the deceased, the family builds a hut on the grave: it is the ghost’s house (h’nam atâu).

For the Bahnar, the ghost continues to live in this hut and to roam around the cemetery area. It regularly receives a monthly offering of pork and chicken from its family. This period of tomb maintenance can last several months or even years. It is linked to the financial situation of the deceased’s family. It ends with a ritual ceremony (or tomb abandonment ceremony) whose purpose is to allow the ghost to definitively join the spirit world (dêh atâu) and to break the deceased’s connection with the living. This spirit thus becomes a « grandfather or grandmother spirit » (atâu bok ja). Unlike the Vietnamese, Nùng, Mường, etc., the Bahnar do not practice ancestor worship.

This ritual ceremony takes place once a year and generally begins at the end of the rainy season. The period chosen is when there is a full moon. This ceremony is somewhat like a secondary burial. It is prepared with care and joy. It is scheduled on an auspicious day by all the heads of the bereaved families in consultation with the village elders and usually lasts three days and three nights. There are three essential stages in this ceremony: rites of construction, abandonment, and liberation. Each stage corresponds to an entire day.

In the first stage, the hut covering the tomb is removed and replaced by a funeral house built with construction materials (bamboo, wood, imperata grass) collected over several weeks. The first day of construction is called « dong boxàt » by the Bahnar. The construction work is always accompanied by dance and music in an indescribable jubilation.

In the second stage, the ritual ceremony always begins in the evening. This is the stage of abandoning the tomb. For the Bahnar, it is nar tuk (or day of abandonment). An offering of alcohol and meat is made to the deceased in the funeral house. Then it is the head of the family who begins a prayer and officiates while the relatives can enter the funeral house and lament for the last time the sudden departure of the deceased. Once the rite is finished, the family of the deceased must circle the funeral house seven times counterclockwise. They are accompanied during this round by men carrying on their shoulders a miniature house (or ghost house) and articulated wooden figurines of various sizes operated by a system of strings attempting to simulate all human activities: rice pounding, weaving, etc.

Not even a couple of figurines in copulation is absent. The Bahnar claim that the animation of these figurines in front of the ghost’s house is intended only to provide entertainment, but some ethnologists believe that there is certainly another meaning compared to the customs of other ethnic groups in the region (those of the Batak from North Sumatra). The procession is accompanied by the women’s dance to the rhythm of gongs struck by men dressed in beautiful clothes and each wearing a feather in their hair. Being the climax of the ceremony, this procession is meant to accompany the ghost into the spirit world.