Version vietnamienne

Version anglaise

Galerie des photos

L’histoire du pont-pagode de Hội An

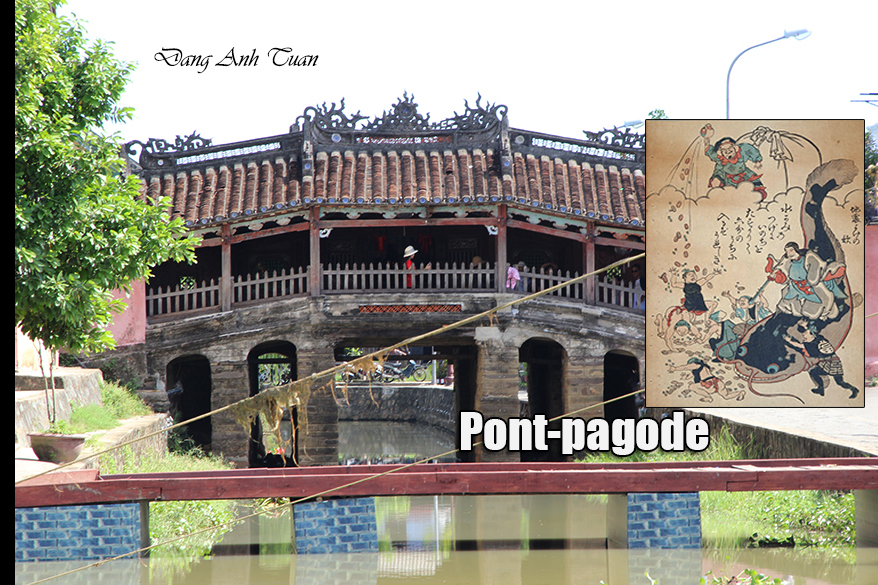

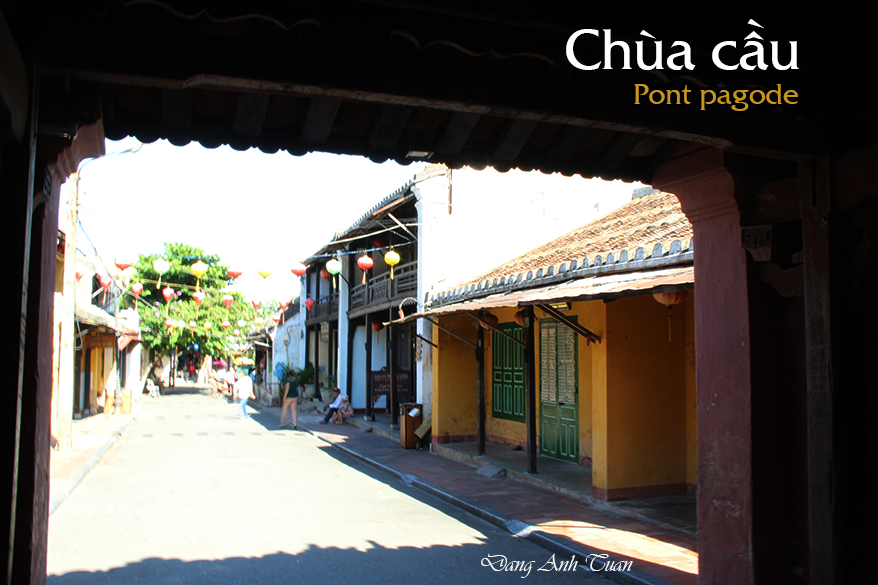

Certains historiens attribuent la construction de ce pont aux Japonais. Ces derniers l’ont-ils construit eux-mêmes ou l’ont-ils réalisé sur la commande des Chinois ? C’est une énigme historique qui reste à éclaircir. D’autres experts réfutent totalement cette hypothèse. Ils estiment que ce pont doit être attribué aux Japonais dans la mesure où celui-ci est destiné à mieux signaler l’entrée du quartier japonais. En tout cas, ce pont s’avère nécessaire car il est établi sur un grand arroyo où les crues surviennent à la saison des pluies dans le but de faciliter la circulation des véhicules, des chevaux et des piétons dans les deux quartiers de Hội An et de relier aujourd’hui les rues de Trần Phú et Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai. Ce pont est constitué de deux parties : le pont lui-même et la pagode. À l’entrée et à la sortie de ce pont on relève la présence de quatre statuettes de chien et de singe. Certains pensent que les travaux de construction ont commencé dans l’année du singe et achevé dans l’année du chien. D’autres attribuent cette présence à un usage japonais qu’il est temps de chercher à comprendre. Quant à la pagode, elle est située à côté de ce pont et en bois. On trouve sur sa porte principale une enseigne intitulée « Lai Viễn Kiều » qui est un autographe royal laissé par le seigneur Nguyễn Phước Châu lors de sa visite en l’an 1719 à Hội An.

Auparavant, cette pagode est dédiée au culte de Huyền Thiên Đại Đế (ou Bắc Đế Trần Vũ), un personnage éminent du taoïsme chargé de gouverner la partie Nord du ciel et d’avoir la mainmise sur le poisson-chat géant (Namazu) vivant dans la vase des profondeurs de la terre. Selon le mythe japonais, cet animal aquatique a la tête au Japon et la queue en Inde et la partie dorsale se trouve à l’endroit où s’érige le pont. Chaque fois qu’il retourne son dos, cela provoque des séismes au Japon et Hội An ne peut pas se tenir dans la paix pour permettre à ses habitants d’avoir la prospérité dans le commerce. C’est pour cela qu’on érige une pagode considérée comme une épée transperçant son dos afin de l’immobiliser et de l’empêcher de faire grands ravages. De toute façon, grâce au talent des architectes de cette époque, on constate que ce pont-pagode peut résister aux crues capricieuses de l’arroyo au fil du temps. Ce pont-pagode devient le symbole représentatif de la vieille ville de Hội An.

Version vietnamienne

Một số sử gia cho rằng việc xây dựng chùa cầu này đến từ người Nhật Bản. Họ tự xây dựng nó hay người Hoa thuê họ làm việc nầy ? Đó là một bí ẩn lịch sử cần được làm sáng tỏ. Các chuyên gia khác bác bỏ hoàn toàn giả thuyết này. Họ tin rằng cầu này được người Nhật dựng lên vì nó nhằm đánh dấu lối vào khu phố Nhật Bản. Trong mọi trường hợp, chiếc cầu này rất cần thiết vì nó được xây dựng trên một con sông lớn, nơi thường xảy ra lũ lụt vào mùa mưa nhằm tạo ra điều kiện thuận lợi cho việc di chuyển xe cộ, ngựa và người đi bộ ở hai khu phố của Hội An và kết nối hai đường phố Trần Phú và Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai ngày nay.

Cầu này gồm hai phần: một phần là cầu và một phần là chùa. Ở lối vào và lối ra của chùa cầu nầy, người ta nhận thấy có sự hiện diện của bốn tượng chó và khỉ. Một số người cho rằng việc xây dựng khởi đầu vào năm Thân và hoàn thành vào năm Tuất. Những người khác cho rằng sự hiện diện này là một tập tục của người Nhật mà cần phải nghiên cứu và tìm hiểu. Về phần chùa, nó nằm sát cạnh cầu này và được làm bằng gỗ. Trên cửa chính cũa chùa có một tấm biển đề « Lai Viễn Kiều » là ngự bút của chúa Nguyễn Phước Châu trong cuộc viếng thăm Hội An vào năm 1719.

Ngôi chùa này được thờ phụng trước kia Huyền Thiên Đại Đế (hay Bắc Đế Trần Vũ), một nhân vật nổi tiếng của Lão giáo, có nhiệm vụ cai trị phần phía bắc của trời và có tài năng kiểm soát được con cá trê khổng lồ sống ở đất bùn từ sâu của lòng đất. Theo truyền thuyết của người Nhật, loài vật sống dưới nước này có đầu ở Nhật Bản, đuôi nằm ở Ấn Độ và phần lưng của nó thì là nơi dựng chùa cầu. Mỗi lần nó quay lưng lại thì gây ra sự động đất ở Nhật Bản và Hội An cũng không thể yên ổn để cho người dân có được sự thịnh vượng trong mậu dịch. Đây là lý do tại sao một ngôi chùa được dựng lên và được xem coi như là một thanh gươm đâm vào lưng nó để cố giữ nó lại và ngăn nó tàn phá. Dù thế nào đi nữa, nhờ sự tài hoa của các nhà kiến trúc sư thời bấy giờ mà chùa cầu này có thể chống chọi với những trận lũ kinh hoàng theo dòng thời gian. Chùa cầu này trở thành ngày nay một biểu tượng tiêu biểu của phố cổ Hội An.

Some historians attribute the construction of this bridge to the Japanese. Did they build it themselves or did they do it on the order of the Chinese? It is a historical mystery that remains to be clarified. Other experts completely refute this hypothesis. They believe that this bridge should be attributed to the Japanese insofar as it is intended to better mark the entrance to the Japanese quarter. In any case, this bridge proves necessary because it is built over a large arroyo where floods occur during the rainy season in order to facilitate the movement of vehicles, horses, and pedestrians between the two quarters of Hội An and today connects Trần Phú and Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai streets. This bridge consists of two parts: the bridge itself and the pagoda. At the entrance and exit of this bridge, there are four statuettes of a dog and a monkey. Some think that the construction work began in the year of the monkey and was completed in the year of the dog. Others attribute this presence to a Japanese custom that it is time to try to understand. As for the pagoda, it is located next to this bridge and is made of wood. On its main door, there is a sign titled « Lai Viễn Kiều, » which is a royal autograph left by Lord Nguyễn Phước Châu during his visit to Hội An in the year 1719.

Previously, this pagoda was dedicated to the worship of Huyền Thiên Đại Đế (or Bắc Đế Trần Vũ), a prominent figure in Taoism responsible for governing the northern part of the sky and having control over the giant catfish (Namazu) living in the mud of the earth’s depths. According to Japanese myth, this aquatic animal has its head in Japan, its tail in India, and its dorsal part is located where the bridge stands. Each time it turns its back, it causes earthquakes in Japan, and Hội An cannot remain peaceful, preventing its inhabitants from prospering in trade. That is why a pagoda was erected, considered as a sword piercing its back to immobilize it and prevent it from causing great destruction. In any case, thanks to the talent of the architects of that time, it is observed that this bridge-pagoda can withstand the capricious floods of the arroyo over time. This bridge-pagoda has become the representative symbol of the old town of Hội An.