Version française

Version française

Version anglaise

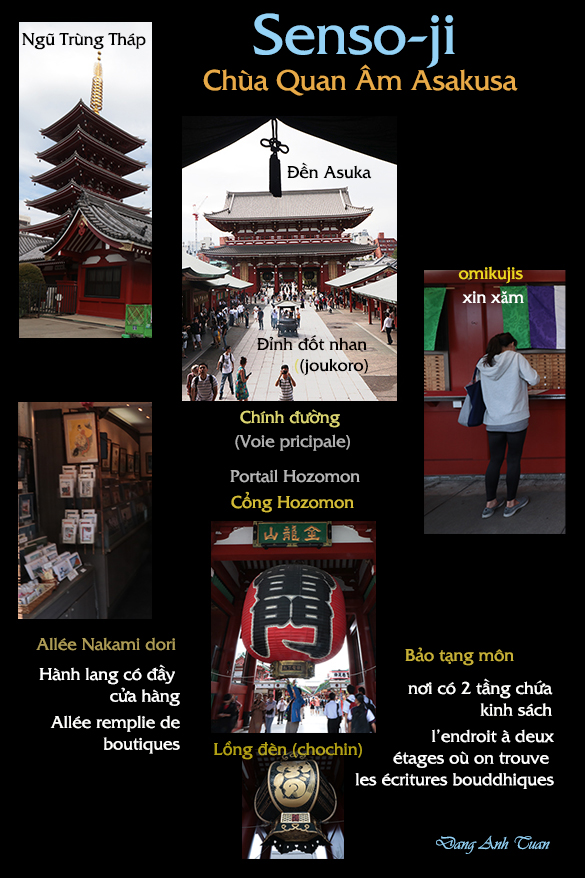

[Schéma de Senso-ji (Tokyo)]

Ngày thứ hai của cuộc hành trình ở Nhật Bản Đến Nhật Bản thường dễ nhận thấy cổng Torii ở trong các thành phố. Cổng nầy là biểu tượng của thần đạo, một tôn giáo bản địa của người dân Nhật. Đây cũng là cổng để phân chia rõ rệt giữa thế giới trần tục và không gian thiêng liêng của Thần đạo. Theo tư tưởng của đạo nầy, vạn vật dù là vật đó sống hay chết ở trong tự nhiên đều có thần (kami) cư ngụ. Có thể vì Nhật Bản là một quốc gia có nhiều thiên tai như các siêu bão, sóng thần, động đất vân vân… khiến người dân ở nơi nầy họ nghĩ rằng có một sức mạnh vô hình nào đến từ những thần linh khiến làm họ lúc nào cũng lo sợ, buộc lòng họ phải kính thờ và thân thiện. Bởi vậy trong mỗi nhà của người dân Nhật thường thấy có một bàn thờ tổ tiên hay là của một vị thần nào quen thuộc. Tổ tiên của vị thiên hoàng Nhật Bản hiện nay cũng cho mình là con cháu của nữ thần mặt trời Amaterasu Omikami. Với tầng lớp nông dân ở xứ Nhật thời đó,vai trò của nhà vua rất quan trọng vì ông là người có khả năng cầu xin nữ thần để được mùa màng. Chính nhờ tư duy thần đạo nầy mà đế chế Nhật Bản vẫn được bảo tồn qua nhiều thế kỷ nhất là vai trò thiêng liêng của thiên hoàng không bao giờ bị tướt đoạt dù quyền lực đã rơi nhiều lần vào các gia đình có thế lực mạnh (Kamakura, Muromachi và Tokugawa). Nước Nhật có đến hiện nay 80.000 thần xã (jinja) (hay đền của Thần đạo) thường nằm trên đồi hay ven vệ đường.

Rất ít người Nhật hiện nay theo thần đạo nhưng những thói quen như óc thẩm mĩ tối giản, chân phương hay thanh tẩy đều bắt nguồn từ thần đạo. Trước khi nhận Phật gíáo làm quốc giáo vào thế kỷ thứ 6 với hoàng tử Shotoku Taishi của dòng dõi Yamato thì người dân Nhật họ đã có thần đạo. Bởi vậy Phật giáo đột nhập vào Nhật Bản, đã có lúc đầu một cuộc xung đột ít nhiều với thần đạo nhưng về sau nhờ có sự hỗn hợp và hoà đồng của hai đạo khiến Phật giáo đã bắt rễ ăn sâu cho đến hiện nay vào đời sống của người dân Nhật. Phật giáo thể hiện được không những tính liên tục hài hoà với thần đạo qua các lễ hội quan trọng (matsuri) mà còn có những nét đặc điểm trong tôn giáo và văn hóa Nhật Bản nhất là về vũ trụ quan và đạo lí nhân sinh. Khi xâm nhập vào Nhật Bản, Phật giáo được biến hóa theo nhu cầu cần thiết và cứu tế của người dân Nhật. Sự hoà nhập Phật giáo vào tín ngưỡng dân gian Nhật Bản cũng được xem tương tự như ở Vietnam với những người theo đạo Phật thờ cúng tổ tiên. Ở đất nước nầy Thần là Phật mà Phật cũng là Thần. Cụ thể là nữ thần Kannon của Senso-ji (Thiền Thảo Tự) trở đi về sau thành Quan Âm bồ tát khi Phật giáo gia nhập xứ Nhật. Đây cũng là một sự kết hợp tính cứu tế của Quan Âm truyền thống với tính phồn thực thấy ở nữ thần Nhật Bản trong tín ngưỡng dân gian bản đia. Bởi thế Quan Âm Nhật Bản còn là vị thần se duyên và phụ sản nữa.

Sáng nay, ngày thứ hai, phái đoàn cùng mình được đi viếng thăm một chủa cổ kính tên là Senso-ji (Thiền Thảo Tự) nằm ở phía bắc của Tokyo. Muốn chỉ chùa chiền, người dân Nhật thường dùng chữ ji hay dera ở cuối tên chủa. Chùa nầy còn có tên là Chùa Quan Âm Asuka vì vào năm 628, có hai người dân chài kéo lưới được một pho tượng của nữ thần Kannon bằng vàng từ sông Sumida. Được biết chuyện nầy, lãnh chúa vùng nầy mới thuyết phục được hai người dân chài và cùng nhau xây một miếu thờ nữ thần Kannon Rồi đến năm 645 có một sư tăng Shokai xây chùa tại đây để thờ phượng. Nhờ sự cúng dường một phần đất lớn cho chùa của Mạc phủ Tokugawa Iaetsu mà diện tích của chùa được tăng thêm. Chùa được nổi tiếng từ đó và trở nên ngày nay là một quần thể chùa đền mà du khách đến tham quan Tokyo không thể bỏ qua vì nó được sùng tu lại và giữ được phong cách kiến trúc cổ kính của thời Edo (Tokyo xưa) dù bị tàn phá trong thế chiến thứ hai. Đến chùa nầy, mọi người phải đi qua cổng chính Kaminarimon thường được gọi là « Cổng sấm »(Lôi Môn). Nơi nầy có hai vị thần gác cổng, một người tên là Fujin (Phong thần bên phải) và Raijin (Lôi thần bên trái). Cổng nầy đựơc du khách chú ý nhất là nhờ có một lồng đèn giấy to tác treo ở giữa cổng nhất là ở dưới đáy có chạm khắc một con rồng rất tinh xảo. Lồng nầy không thay đổi qua bao nhiều thế kỷ theo dòng lịch sử.

Phiá sau các thần nầy, còn có hai tượng thần Kim Long và Thiên Long một nữ, một nam, cả hai là thần nước để nhắc đến có sự liên quan mật thiết với sông Sumida, nơi mà tìm ra Phật mẫu. Khó mà chụp hình rõ ràng vì có lẽ người dân Nhật sợ thất lễ phạm thượng nhất đây là các thần (kami) của Thần đạo. Sau cùng, du khách sẻ găp ngay đường Nakamise-dori dài 250 thước. Đường nầy có rất nhiều mặt hàng bán đồ đặc sản và thủ công truyền thống làm rất tinh xảo như đai lưng obi, quạt giấy, lược chải tóc, búp bê Nhật vân vân … Gần cuối đường, du khách sẽ gặp một một đỉnh đốt nhang (joukoro) lúc nào cũng có người đứng xung quanh đốt nhang, khói bốc nghi ngút. Họ cầu nguyện mong đựợc sức khoẻ hay may mắn. Bên phải của đỉnh đốt nhang thì có các máy xin xăm (omikujis) . Đây là một loại giấy tiên đoán tương lai mà du khách bỏ tiền vào máy kéo bắt thăm. Một dạng loto. Còn phiá bên trái của đỉnh nhìn về đằng xa sẽ thấy một ngôi chùa 5 tầng, nơi giữ tro cốt của Đức Phật Thích Ca. Sau đó du khách sẻ đến cổng Hozomon (hay là Bảo Tạng Môn) trước khi vào chùa Sensoji thật sự. Cổng nầy được xây lại vào năm 1964 bằng bê tong cột thép có hai tầng và có một căn nhà chứa rất nhiều kinh Phật chữ Hán ở thế kỷ 14. Nơi nầy, trước cổng có bố trí hai tượng Kim Cương lực sĩ và có một lồng đèn (chochin) nặng 400 kilô kèm theo hai toro ở hai bên với vật liệu bằng thau trông rất xinh đẹp, mỗi toro nặng có một tấn.

Sau cổng Hozomon, du khách sẻ đến điện chính nơi thờ nữ thần Kannon hay Quan Thế Âm Bồ Tát. Điện nầy có hai gian. Gian truớc dành cho tín đồ Phật tử còn gian sau thì dành cho cúng kiến Phật mẫu và không được vào. Một khi vào bên trong của gian ngoài của điện thì sẽ thấy một ngôi miếu mạ vàng hiện ra nơi thờ bức tượng Quan Âm đã có từ thưở xưa. Các tín đồ thể hiện lòng kính có thể đốt nhan và ném tiền xu. Rất ít có thì giờ cho mình để ngắm nghiá, chỉ vỏn vẹn mua vài đôi đũa và chụp hình để lưu niệm (45 phút mà HDV dành cho đoàn trong thời gian tham quan). Một kỷ niệm khó quên, một ngôi chùa quá đẹp của thời Edo, một khu phố náo nhiệt và sầm uất trong một không gian tôn nghiêm và tĩnh lăng ….

Đến xử Phù Tang mới biết thêm một chuyện về các nhà sư « ăn thịt lấy vợ ». Các ông nầy có quyền lập gia đình và có quyền giữ chức vụ cha truyền con nối để trù trì, thật là một chuyện khó tin nhưng thật sự là vậy. Làm sư có rất nhiều tiền lắm vì có nhiều lợi tức trước hết là nhờ có đất chùa từ bao nhiêu thế kỷ nên cho các tiệm buôn bán thuê mướn truớc chùa hay là lo việc buôn bán đất mộ táng. Sỡ dĩ chùa có nhiều đất đó là nhờ các lãnh chúa cúng dường một thuở xa xôi cho chùa xem như đó là một thứ lễ vật để cầu phúc hay sám hối. Vì thế đất trở nên sở hữu của chùa và trở thành một lợi tức không nhỏ cho việc sinh sống của nhà sư. Đất chật ngưòi đông như ở Nhật Bản nên đất làm mộ táng là một loại kinh doanh siêu lợi nhuận. Người Nhật lúc còn sống thì theo đạo thần, công giáo hay vô đạo. Lúc về già gần chết thì muốn theo đạo Phật để về Tây Phương cực lạc.

Vì vậy nhất định theo đạo Phật, tốn cả triệu Yên để mua miếng đất mộ táng ở chùa mà muốn vậy thì phải là Phật tử tức là phải trải qua các nghi thức của chùa để có pháp danh mới có quyền mua đất ở chùa. Bao nhiêu tiền được sư thu thập không có đóng thuế nhất là còn thêm tiền chăm sóc các mộ táng mỗi năm và tiền đi ra ngoài làm Phật sự những lúc có người cần đến. Bởi vậy lấy sư là có một tương lai rực rỡ cùng nghề làm võ sĩ sumo. Đây là hai nghề được các cô yêu chuộng hiện nay nhất ở Nhật Bản. Hướng dẩn viên Ngọc Anh nói đến chuyện các sư Nhật làm mình cười nhớ đến sư trù trì của chùa Ba Vàng ở miền bắc Vietnam. Người dân Nhật họ có một tư cách hành sự vô cùng phức tạp về tôn giáo nhất là họ có đầu óc rất thực tiễn: họ đi lễ của thần đạo vào năm mới, đến chùa chiền của đạo Phật vào lúc mùa xuân và tổ chức tiệc tùng và tặng quà cho nhau theo đạo Kitô lúc Noël.

La pagode Senso-ji de Tokyo

En débarquant de l’avion au Japon, le touriste a l’habitude de voir fréquemment les toriis de couleur vermillon dans les villes. Ces portails sont le symbole caractéristique du Shintoïsme, une religion locale des Japonais. Ils reflètent aussi la délimitation de la frontière entre le monde profane et l’espace sacré du sanctuaire shintoïste. Selon la pensée de cette religion, tout être vivant ou mort dans la nature doit être habité par un esprit maléfique ou bénéfique (kami). À cause des calamités fréquentes comme les typhons, tsunamis, séismes etc. au Japon, cela inspire profondément à ses habitants la certitude d’une force interne (ou énergie) invisible venant des esprits (kamis). C’est pour cela qu’ils sont constamment peureux et angoissés face à ces esprits et ils sont obligés de les vénérer dans le but de les apprivoiser et les remercier de leur protection dans une vie éphémère soumise au temps. Dans chaque maison japonaise, il y a toujours un autel réservé pour les ancêtres ou pour un « kami » familier. Les ancêtres de l’actuel empereur japonais ont reconnu d’être les descendants de la déesse du Soleil Amaterasu Omikami. Pour les paysans japonais de cette époque, le rôle de l’empereur est très important car il a la possibilité de demander les faveurs auprès de la déesse pour avoir de bonnes récoltes. C’est grâce au shintoïsme que l’empire japonais est préservé durant des siècles.

Le rôle sacré de l’empereur n’est pas confisqué non plus malgré que le pouvoir de décision était revenu plusieurs fois aux mains des shoguns.(Kamakura, Muromachi et Tokugawa). Le Japon a aujourd’hui 80.000 temples shintoïstes (jinja) situés sur les collines ou au bord des routes. Peu de Japonais sont aujourd’hui shintoïstes mais les habitudes telles que l’esprit esthétique minimaliste, la purification ou la sincérité sont empruntées dans le shintoïsme. Avant de reconnaître le bouddhisme comme la religion d’état au 6ème siècle avec le prince Shotoku Taishi de la lignée Yamato, les Japonais ont déjà eu le shintoïsme. C’est pourquoi une fois implanté au Japon, le bouddhisme est au début, en situation de conflit plus ou moins prononcé avec le shintoïsme mais il y a à la fin une sorte de syncrétisme s’opérant entre les deux religions lorsque le bouddhisme réussit à s’enraciner jusqu’à aujourd’hui dans la vie quotidienne des Japonais. Le bouddhisme montre non seulement sa voie à une intégration harmonieuse avec le shintoïsme à travers les fêtes importantes (matsuris) mais aussi ses traits caractéristiques dans la religion et la culture du Japon, notamment dans le cosmos et la moralité humaine. Lors de son invasion au Japon, le bouddhisme s’est transformé en fonction des besoins d’aide nécessaires apportés aux Japonais. L’intégration du bouddhisme dans les croyances populaires japonaises est similaire à celle du Vietnam où les adeptes du bouddhisme vénèrent leurs ancêtres.

Dans ce pays, la divinité est un Bouddha et inversement. La preuve est que la déesse Kannon du temple Senso-ji est devenue plus tard un Boddhisattva quand le bouddhisme réussit à s’implanter au Japon. Cela montre la combinaison d’un Boddhisattva traditionnel et du caractère de fertilité de la déesse japonaise dans la croyance populaire locale. C’est pourquoi le Boddhisattva japonais est aussi une déesse de mariage et de procréation. Au matin du deuxième jour, le groupe de touristes et moi, nous allons visiter la pagode Senso-ji située dans le nord de la capiale Tokyo. Quand le nom d’un monument est terminé par ji ou dera, il s’agit bien d’une pagode. Cette pagode est connue aussi sous le nom « Asuka » car elle est située dans un quartier très animé Asuka. En 628, il y avait deux pêcheurs réussissant à capturer dans leur filet une statue en or représentant la déesse Kannon dans le fleuve Sumida. Étant au courant de ce fait, un seigneur local réussît à les convaincre et à réaliser ensemble un autel dédié à cette déesse. Puis en 645, un moine de nom Shokai décida de construire à la place de cet autel un temple bouddhiste. C’est la pagode Senso-jì. Grâce aux donations de terrain effectuées par le shogun Tokugawa Iaetsu, la pagode commença à grandir et à changer d’aspect pour devenir jusqu’à aujourd’hui un complexe de pagodes et de temples shintoïstes dont le touriste ne peut pas se passer lorsqu’il a l’occasion de visiter la capitale Tokyo.

C’est aussi une très ancienne pagode connue pour son charme et sa beauté retrouvée de l’époque Edo malgré la destruction provoquée durant la deuxième guerre mondiale. Pour entrer dans cette pagode, tout le monde doit emprunter le porche principal connu sous le nom « Kaminarimon » (ou porte de tonnerre) et protégé par deux divinités Fujin (déesse du vent) et Raijin (dieu de la foudre). L’attention des touristes est retenue par la présence d’une lanterne gigantesque suspendue au milieu du porche et dont le fond contient un beau dragon sculpté en ronde bosse. Cette lanterne ne subit pas des modifications majeures au fil des siècles de l’histoire de la pagode. Derrière ces divinités shintoïstes, il y a encore un couple d’esprits de l’eau ( une déesse Kim Long et un dieu Thiên Long) rappelant le lien intime avec le fleuve Sumida où a été trouvée la statue Bodhisattva en or.. C’est difficile de bien faire les photos car les Japonais ont mis la grille métallique autour de ces kamis dans le but de les protéger et de ne pas les offenser. Puis le touriste se retrouve dans la rue marchande Nakamise-dori longue de 250 mètres. Celle-ci a plusieurs boutiques spécialisées dans la pâtisserie et dans l’artisanat traditionnel avec des produits de qualité comme les peignes, ceintures Obi, éventails, poupées etc.

Cette rue se termine sur un parvis où trône un joukoro (un brûleur d’encens) autour duquel il y a toujours des gens continuant à brûler des encens dans un atmosphère rempli de fumée pour demander la bénédiction de la déesse. Sur la droite de ce parvis, on trouve des machines destinées à imprimer des omikujis. Ceux-ci sont des papiers sacrés que l’on récupère par tirage au sort pour prédire l’avenir du demandeur. C’est une sorte de loterie sacrée.

Sur la droite de ce parvis, on voit apparaître la pagode à cinq étages où les cendres de Siddharta Gautama sont soigneusement conservés. Le deuxième porche monumental est connu sous le nom de Hozomon. Celui-ci a été gardé à son entrée par deux dieux gardiens impressionnants et construit en béton avec les colonnes en acier dans les années 1964. Hozomon a deux étages dont le deuxième est destiné à contenir des sutras écrits en chinois et datant du 14ème siècle. C’est ici qu’on trouve un chochin (une sorte de lanterne) de 400 kilos entouré de chaque côté par un beau toro en laiton, chacun pesant au moins une tonne. Derrière ce porche monumental, c’est le bâtiment principal (Kannon-do) de la déesse Kannon. Il est divisé en deux parties: la partie extérieure est réservée aux fidèles tandis que la partie intérieure est interdite au public car il y a l’autel doré de la déesse Kannon.

Notre groupe dispose seulement de 45 minutes pour visiter Senso-ji car après cette visite, nous devons participer à un cours d’initiation au thé japonais. Un souvenir inoubliable, une belle pagode de l’époque Edo, un quartier très animé dans un espace serein.

Upon disembarking from the plane in Japan, tourists are accustomed to frequently seeing vermilion-colored torii gates in the cities. These gates are the characteristic symbol of Shintoism, a local religion of the Japanese. They also reflect the boundary between the profane world and the sacred space of the Shinto shrine. According to the beliefs of this religion, every living or dead being in nature must be inhabited by an evil or benevolent spirit (kami). Due to frequent calamities such as typhoons, tsunamis, earthquakes, etc., in Japan, this deeply inspires its inhabitants with the certainty of an internal force (or energy) invisible that comes from the spirits (kamis). This is why they are constantly fearful and anxious in the face of these spirits and are obliged to venerate them in order to tame them and thank them for their protection in an ephemeral life subject to time. In every Japanese home, there is always an altar reserved for ancestors or a familiar « kami. » The ancestors of the current Japanese emperor have recognized themselves as descendants of the Sun goddess Amaterasu Omikami. For the Japanese peasants of that time, the role of the emperor was very important because he had the ability to request favors from the goddess to have good harvests. It is thanks to Shintoism that the Japanese empire has been preserved for centuries.

The sacred role of the emperor has not been confiscated either, despite the fact that decision-making power has several times returned to the hands of the shoguns (Kamakura, Muromachi, and Tokugawa). Today, Japan has 80,000 Shinto shrines (jinja) located on hills or by the roadside. Few Japanese people are Shintoists today, but habits such as the minimalist aesthetic spirit, purification, or sincerity are borrowed from Shintoism. Before recognizing Buddhism as the state religion in the 6th century with Prince Shotoku Taishi of the Yamato lineage, the Japanese already had Shintoism. That is why, once Buddhism was introduced to Japan, it was initially in a situation of more or less pronounced conflict with Shintoism, but in the end, a kind of syncretism occurred between the two religions when Buddhism succeeded in taking root up to the present day in the daily life of the Japanese. Buddhism not only shows its path to harmonious integration with Shintoism through important festivals (matsuris) but also its characteristic traits in the religion and culture of Japan, notably in the cosmos and human morality. During its introduction to Japan, Buddhism transformed according to the necessary aid it provided to the Japanese. The integration of Buddhism into Japanese popular beliefs is similar to that of Vietnam, where Buddhists venerate their ancestors.

In this country, the deity is a Buddha and vice versa. The proof is that the goddess Kannon of the Senso-ji temple later became a Bodhisattva when Buddhism managed to establish itself in Japan. This shows the combination of a traditional Bodhisattva and the fertility character of the Japanese goddess in local popular belief. That is why the Japanese Bodhisattva is also a goddess of marriage and procreation. On the morning of the second day, the group of tourists and I went to visit the Senso-ji pagoda located in the north of the capital Tokyo. When the name of a monument ends with ji or dera, it is indeed a pagoda. This pagoda is also known as « Asuka » because it is located in a very lively district called Asuka. In 628, there were two fishermen who succeeded in catching in their net a golden statue representing the goddess Kannon in the Sumida River. Being aware of this fact, a local lord managed to convince them and together they built an altar dedicated to this goddess. Then in 645, a monk named Shokai decided to build a Buddhist temple in place of this altar. This is the Senso-ji pagoda. Thanks to land donations made by the shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu, the pagoda began to grow and change in appearance to become, up to today, a complex of pagodas and Shinto temples that tourists cannot miss when they have the opportunity to visit the capital Tokyo.

It is also a very ancient pagoda known for its charm and its beauty restored from the Edo period despite the destruction caused during World War II. To enter this pagoda, everyone must pass through the main gate known as « Kaminarimon » (or Thunder Gate), guarded by two deities: Fujin (the wind goddess) and Raijin (the god of thunder). Tourists’ attention is drawn to the presence of a gigantic lantern hanging in the middle of the gate, with a beautiful dragon sculpted in high relief on its base. This lantern has not undergone major modifications over the centuries of the pagoda’s history.

Behind these Shinto deities, there is also a pair of water spirits (a goddess Kim Long and a god Thiên Long) reminding of the close connection with the Sumida River where the golden Bodhisattva statue was found. It is difficult to take good photos because the Japanese have placed a metal grille around these kami to protect them and not to offend them. Then the tourist finds themselves on Nakamise-dori shopping street, 250 meters long. It has several shops specializing in pastries and traditional crafts with quality products such as combs, Obi belts, fans, dolls, etc.

This street ends on a forecourt where a joukoro (an incense burner) stands, around which there are always people continuing to burn incense in an atmosphere filled with smoke to ask for the goddess’s blessing. On the right of this forecourt, there are machines intended to print omikujis. These are sacred papers that are drawn by lot to predict the future of the seeker. It is a kind of sacred lottery.

On the right of this forecourt, the five-story pagoda appears, where the ashes of Siddharta Gautama are carefully preserved. The second monumental gate is known as Hozomon. It has been guarded at its entrance by two impressive guardian gods and was built in concrete with steel columns in the 1960s. Hozomon has two stories, the second of which is intended to contain sutras written in Chinese dating from the 14th century. Here you find a chochin (a kind of lantern) weighing 400 kilos, flanked on each side by a beautiful brass toro, each weighing at least a ton. Behind this monumental gate is the main building (Kannon-do) of the goddess Kannon. It is divided into two parts: the outer part is reserved for worshippers, while the inner part is forbidden to the public because it houses the golden altar of the goddess Kannon.

Our group only has 45 minutes to visit Senso-ji, as afterward we are required to participate in an introductory Japanese tea class. An unforgettable memory, a beautiful Edo-period pagoda, a lively neighborhood in a serene space.