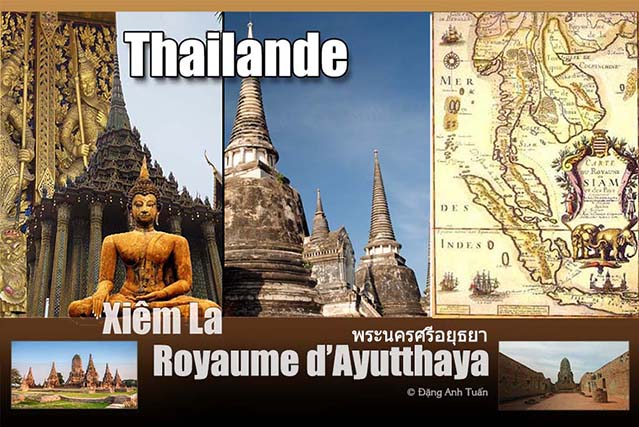

Le royaume de Sukhothai ne survécut pas après la disparition du grand roi Rama Khamheng car ses successeurs Lo Tai (1318-1347) et Lu Tai (1347-1368), accaparés par la foi religieuse négligeaient de veiller sur leurs vassaux parmi lesquels il y avait un prince brave et énergique d’U Thong (*) connu pour ses ambitions territoriales. Celui-ci n’hésita pas à soumettre Lu Tai de Sukhothai. Il devint ainsi le fondateur de la nouvelle dynastie en prenant Ayutthaya située dans la basse vallée du Ménam Chao Praya pour capitale. Il prit le titre de Ramathibodi 1er (ou Rama le Grand) (ou Ramadhipati). Son royaume n’était pas unifié au sens strict du terme mais il était en quelque sorte un mandala(**). Le roi était au centre de plusieurs cercles concentriques du système mandala. Le cercle le plus lointain était constitué de principautés autonomes (ou muäng ) gouvernées chacune par un membre de la famille royale tandis que le cercle le plus proche était aux mains des gouverneurs nommés par le roi. Un édit datant de 1468 ou 1469 rapporta qu’il y avait 20 rois vassaux rendant hommage au roi d’Ayutthaya.

พระนครศรีอยุธยา

©Đặng Anh Tuấn

(*) U Thong: district situé dans la province de Suphanburi. C’est le royaume de Dvaravati que les Chinois ont désigné souvent sous le nom de T’o Lo po ti. C’est ici que le moine chinois célèbre Huan Tsang (Huyền Trang) était de passage lors de son voyage en Inde pour ramener des textes originaux bouddhiques.

(**) Terme mandala employé par WOLTERS,O.W.1999. History, Culture and Religion in Southeast Asian Perspectives. Revised Edition, Ithaca, Cornell university and the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp 16-28.

Malgré cela, son emprise et son autorité étaient relatives sur des principautés éloignées pouvant afficher à tout moment leur indépendance et leur prétention avec leurs chefs charismatiques. Son rôle religieux (dharmarâja) servit de contrepoids à la rivalité potentielle de ces rois vassaux. C’est pourquoi le royaume d’Ayutthaya connut souvent des guerres de succession et des luttes internes durant son existence.

A son apogée, le royaume d’Ayutthaya occupa à peu près le territoire de la Thailande d’aujourd’hui amputé du royaume tampon de Lanna (dont la capitale était Chiangmai ) et d’une partie de l’Est en Birmanie. Selon le chercheur Nguyễn Thế Anh, ce type de configuration politique se retrouva aussi pour un certain temps au début du XIème siècle au Vietnam mais il disparut au profit de la la centralisation du pouvoir dans la capitale au moment du transfert de cette dernière à Thăng Long (Hànội) sous le règne de Lý Thái Tổ (Lý Công Uẩn).

Selon l’historien thaïlandais Charnvit Kasetsiri, ce prince d’U Thong était issu d’une famille chinoise. Grâce à l’alliance matrimoniale avec le roi de Lopburi, il réussît à s’imposer pour succéder à ce dernier. Dès lors, Ayutthaya devint le centre du pouvoir politique siamois jusqu’à sa destruction par les Birmans du roi Hsinbyushin en 1767. Expansionniste, Ramathibodi ne tarda pas à prendre Angkor en 1353. Cela se renouvela encore deux fois avec Ramesuen (le fils du roi Ramathibodi) en 1393 et avec Borommaracha II en 1431. Les Khmers furent obligés de transférer leur capitale à Phnom Penh avec le roi khmer Ponheat Yat. Malgré leur mise à sac d’Angkor, les rois d’Ayathuya continuèrent à se poser volontiers en héritiers des rois de l’empire angkorien. Ils reprirent à leur compte non seulement l’organisation de la cour et la titulature des vaincus mais aussi leurs danseuses et leurs parures. Le retour à la tradition de la monarchie angkorienne était manifeste. Le roi devint en quelque sorte un dieu vivant dont l’apparition publique était rare. Ses sujets ne pouvaient plus le regarder en face sauf ses proches familiaux. Ils devaient lui adresser la parole dans un langage spécifique employé pour la royauté. Doté d’un pouvoir divin, le roi pouvait décider du sort de ses sujets. C’est sous le règne de Ramathibodi qu’une série de réformes fut entamée. Il fit venir les membres de la communauté monastique cinghalaise dans le but d’établir un nouvel ordre religieux. En 1360, le bouddhisme theravadà devint la religion officielle du royaume. Un code juridique incorporant la coutume thaïe et basé sur le Dharmashāstra hindou fut adopté. Quant à l’art d’Ayutthaya, il évolua au début sous l’influence de l’art de Sukhothai. Puis il continua à trouver son inspiration dans le domaine de la sculpture avant de retourner aux modèles khmers au moment où le roi Trailokanatha succéda à son père sur le trône en 1448. Bref, on trouve dans le style d’Ayutthaya un mélange du style de Sukhothai et du style khmer.

Etant décrite par l’abbé de Choisy, membre d’une délégation française envoyée en 1685 par le roi Louis XIV auprès du roi siamois Narai comme une ville cosmopolite et merveilleuse, Ayutthaya devint très vite la proie des convoitises birmanes à cause de sa richesse et de sa grandeur. Malgré la signification du nom porté en sanskrit ( « forteresse imprenable »), elle fut pillée et dévastée par les Birmans du roi de Toungoo Bayinnaung en 1569. Puis elle fut mise à sac de nouveau par les Birmans du roi Hsinbyushin en 1767. Les Birmans profitèrent de cette occasion pour faire fondre l’or qui recouvrait les statues de bouddha mais ils délaissèrent un autre bouddha en stuc dans l’un des temples de la capitale. Pourtant se trouve sous le stuc, la statue en or massif. Il s’agit bien d’un stratagème employé par les moines siamois pour dissimuler le trésor au moment où les Birmans assiégeaient la capitale. Ce bouddha doré est actuellement dans le Wat Traimit situé au coeur du quartier chinois à Bangkok.

Après la destruction de la capitale Ayutthaya, les Birmans se retirèrent en emmenant non seulement les butins et les prisionniers (60.000 siamois au moins ) mais aussi le roi d’Ayutthaya et sa famille. Dès lors, le royaume d’Ayutthaya fut démembré complètement avec l’apparition de plusieurs seigneurs locaux. Sa capitale n’était plus le centre de pouvoir politique. Selon l’anthropologue américain Charles Keyes, Ayutthaya ne recevait plus les influences cosmiques nécessaires à sa pérennité. Sa raison d’être n’est plus justifiée. Elle sera bientôt remplacée par la nouvelle capitale Thonburi, tout proche de Bangkok, accessible par la mer (en cas de l’invasion birmane ) et fondée par le gouverneur de la province Tak de nom Sin. C’est pourquoi on est habitué à l’appeler Taksin (ou Trịnh Quốc Anh en vietnamien) ou Taksin le Grand dans l’histoire de la Thaïlande.

Etant d’origine chinoise Teo chiu (Tiều Châu), celui-ci réussît à s’imposer comme l’unificateur et le libérateur de la Thaïlande après avoir éliminé tous les prétendants et vaincu les Birmans à Ayutthaya après deux jours de combats acharnés. Son règne ne dura que 15 ans (1767-1782) . Pourtant c’est sous son règne que la Thaïlande retrouva non seulement l’indépendance mais aussi la prospérité. Elle devint aussi l’un des états puissants de l’Asie du Sud Est en réussissant à libérer définitivement le royaume concurrent de Lanna (Chiang Mai) du joug birman en 1774 et en étendant son influence et sa vassalité sur le Laos et sur le Cambodge par des expéditions militaires. Elle commença à s’intéresser à la position stratégique que joua au début du 18ème siècle la principauté de Hà Tiên gouvernée par un Chinois cantonais Mac King Kiou (ou Mạc Cửu en vietnamien), hostile à la nouvelle dynastie des Qing (Mandchous) dans le golfe de Siam. Elle caressa toujours l’idée de monopoliser et de contrôler le commerce dans le golfe de Siam.

C’est au Laos que les Thaïs dirigés par le général Chakri ( futur roi Rama 1er) ont pris le Bouddha d’émeraude aux Laotiens et l’ont ramené à Thonburi en 1779 avant de l’installer définitivement au palais royal de Bangkok. Ce Bouddha devient ainsi le protecteur de la dynastie Chakri et le garant de la prospérité de la Thaïlande.

Etant morcelé en trois entités: le royaume de Vientiane, le royaume de Luang Prabang et le royaume de Champassak après la mort d’un grand roi du Laos, Surinyavongsa, le Laos tomba provisoirement sous le joug thaïlandais. Par contre, au Cambodge, profitant des dissensions internes liées à la succession du trône et ayant toujours la politique expansionniste vers l’est dans le but de contrôler complètement le golfe de Siam, les Thaïs n’hésitèrent pas à entrer en conflit armé avec les Vietnamiens des seigneurs Nguyễn ayant jusqu’alors un droit de regard sur le Cambodge qui avait accordé aux Vietnamiens des facilités d’installation dans son territoire (Cochinchine) avec le roi Prea Chey Chetta II en 1618.

Conflits larvés avec le Vietnam

Bibliographie:

Cổ sử cá quốc gia Ấn Độ hóa ở Viễn Đông. G. E. Coedès. Nhà xuất bản Thế Giới 2011.

La féodalité en Asie du Sud Est, Nguyễn Thế Anh. Paris, PUF,1998, pp. 683-714

La conquête de la Cochinchine par les Nguyễn et le rôle des émigrés chinois. Paul Boudet. BEFEO, Tome 42, 1942, pp 115-132

Contribution à l’étude des colonies vietnamiennes en Thailande. Bùi Quang Tung

Guerres et paix en Asie du Sud Est. Nguyễn Thế Anh- Alain Forest. Collection Recherches asiatiques dirigées par A. Forest. Editeur L’Harmattan.

Thailand and the Southeast Asian networks of the Vietnamese Revolution,1885-1954. Christpher E. Goscha