Forbidden city of Pékin

Cố Cung

[The Forbidden City in Beijing: Part 1]

After defeating his nephew Zhu Yunwen (also known as Jianwen Emperor), whose death remains a mystery to historians, the third emperor of the Ming dynasty, Zhu Di (also known as Yongle Emperor), decided to move the capital from Nanjing to Beijing, mainly for strategic reasons. Facing the serious threat of the Mongols to the empire, he thought this was the quickest solution to deal with the raids. He entrusted the chief architect, the eunuch Nguyen An of Vietnamese origin, with the construction of the Forbidden City on the ruins of Khanbaliq, the Yuan dynasty city built by Kubilai Khan in 1267 and described by Marco Polo in his book titled « The Description of the World » in 1406, following a designated protocol. Two hundred thousand workers were recruited for this grand project, which lasted 14 years.

Besides the participation of a large number of provinces in supplying materials: Xuzhou (Jiangsu) marble, Linqing (Shandong) bricks, stone from the Fangshan and Panshan quarries not far from Beijing, nanmu wood for the house frame from Sichuan, columns from Guizhou and Yunnan, and so on, it was also necessary to renovate the Grand Canal dating back to the Sui Dynasty. This canal was essential for transporting materials and food to the capital Beijing. From 1420 to 1911, a total of 24 emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties resided here. The last emperor to live in this Forbidden City was Emperor Puyi of the Qing Dynasty.

There are many questions about the preservation and conservation of the capital by the Qing army when they seized power in China because, according to Chinese tradition, the victors usually thoroughly destroyed all palaces belonging to previous dynasties. One can look at the example of Zhu Yuanzhang, also known as the Hongwu Emperor. He ordered his soldiers to completely destroy the capital of the Yuan Dynasty in Beijing and move the capital to his hometown in Nanjing. It is unclear what motivated the Qing Dynasty to keep the Ming capital intact.

Cố Cung

Although the Qing emperors made efforts to renovate the Forbidden City and built many additional palaces, this Forbidden City forever retains the mark of its founder, Emperor Yongle (Zhu Di). One of the three famous emperors alongside Han Wudi and Tang Taizong in Chinese history, Zhu Di appointed Admiral Zheng He to lead the naval expeditions to the « Western Oceans, » which were later recorded by his companion Ma Huan in the book titled Ying-yai Sheng-lan (The Marvels of the Oceans). Taking advantage of the usurpation of the throne by Hồ Quý Ly, Zhu Di annexed Vietnam in 1400. Without the nearly ten years of resistance by the Vietnamese people under Lê Lợi, Vietnam could surely be a province of China today, like Yunnan or Guangdong.

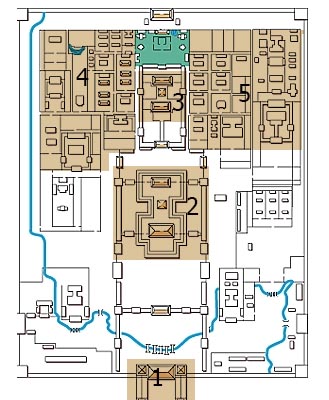

1 Porte du Midi (Ngọ Môn)

2 Tiền Triều (Waichao)

- Điện Thái Hoà (Taihe)

- Điện Trung Hoà (Zhonghe)

- Điện Bảo Hoà (Baohe)

3 Hậu tẩm (Neichao)

- Cung Càn Thanh (Qianqing)

- Điên Giao Thái (Jiaotai)

- Cung Khôn Ninh (Kunning)

4) Six Palais de l’Ouest (Lục viện)

5) Six Palais de l’Est (Luc viện)

The Forbidden City is truly a city within a city and was built on a rectangular piece of land measuring 960 chi in length and 750 chi in width. The Forbidden City is divided into two parts: the front section called the Outer Court (waichao), designated for ceremonial life (such as coronation ceremonies, investiture ceremonies, and royal weddings), and the rear section called the Inner Court, reserved for the emperor and his family. There are three halls in the Outer Court: the Hall of Supreme Harmony, the Hall of Central Harmony, and the Hall of Preserving Harmony, which together form the complex known as the Three Halls of the Outer Court. In the Inner Court, there are the Palace of Heavenly Purity, the Hall of Union, and the Palace of Earthly Tranquility, each surrounded on the east and west sides by six six-yards (residential quarters). This is commonly referred to as the Three Palaces and Six Yards of the Forbidden City.

When visiting the Imperial City, tourists are obliged to pass through Ngo Mon Gate. This is the main gate of the Imperial City. At one time, this gate witnessed many ceremonies related to military departures or the triumphant return of the royal army, as well as the announcement of a new lunar calendar. It is the only gate, or more precisely, a U-shaped structure, 8 meters high, with five buildings on top featuring double roofs and five gates, but the middle gate is reserved only for the king. This architectural complex is often called the Five Phoenix Pavilion because its shape resembles a phoenix. Beyond Ngo Mon Gate, there is a very wide courtyard crossed by an artificial river with shimmering golden water called Neijindhuihe. This river has five beautifully decorated bridges, with the middle bridge reserved for the emperor. Along the riverbanks, there are stone balustrades carved with dragons and phoenixes.

The front court enjoys Yang energy, so the palaces here are usually built higher than the palaces in the rear chambers, thanks to a large common foundation with three steps carved from jade stone, raised to highlight not only the splendor of the front court palaces but also the majestic and magnificent nature of Yang energy. Similarly, the rear chambers enjoy Yin energy, so the palaces here are all low, except for the Kien Thanh Palace, where the king works and discusses state affairs with high-ranking officials, which enjoys Yang energy and is therefore taller than the other palaces.

In this place, one can see a typical metaphor, which is Yang within Yin, often mentioned. Between the Qianqing Palace, where the emperor resides and enjoys Yang energy, and the Kunning Palace, the empress’s resting place receiving Yin energy, there is the Jiaotai Hall. Considered the connecting link between the Qianqing and Kunning Palaces, Jiaotai Hall not only represents the perfect harmony of Yin and Yang but also symbolizes peace within the Forbidden City. All the palaces in the Forbidden City face south to benefit from the advantages of Yang energy.

Based on traditional Chinese feng shui, to the north of the Forbidden City, there is an artificial mountain called Jinshan and the Great Wall to prevent the harmful effects of Yin energy coming from the north (cold winds, nomads, ghosts, and so on). To the south, thanks to water-filled pits and an artificial river with shimmering golden water (Neijindhuihe), the qi buried in the earth can circulate, which is difficult to disperse due to the levels created on the surface. This arrangement is seen in the construction of the three-tiered foundation for the three halls used for rituals in the front court. As a result, qi is guided up and down through the halls to break the monotony of the flat land and reach the summit where the emperor’s throne is in the Hall of Supreme Harmony. As the connection between Heaven and Earth, the emperor usually faces south, with his back to the north, the east on his left, and the west on his right.

Each direction is protected by a guardian creature: the pink swallow in the south, the black turtle in the north, the blue dragon (qinglong) in the east, and the white tiger (baihu) in the west. On the ceiling, at the vertical axis of the throne and above the emperor’s head, there is an exquisitely decorated celestial dome featuring a recessed panel with two golden dragons carved playing with a huge pearl. It is here, when visiting, that tourists wonder how many dragons are used in the decoration of this palace, as this guardian creature appears everywhere. According to some records, there are a total of 13,844 dragons of various types and sizes, giving this place a solemn and majestic appearance never seen in other palaces.

Located along the main north-south axis, the Forbidden City is decorated according to rules of numbers and colors. The choice of Yang numbers (or odd numbers) is commonly seen through the arrangement of mythical creatures on the eaves of the palace roofs or the ornate display on the doors of the Forbidden City with yellow nails, as well as the number of bays the Forbidden City has.

The number of divine beasts on the eaves corners of the palace can range from 1 to 10. Depending on the importance and scale of the palace as well as the rank of the owner in the court, this number can vary. The number of these divine beasts is specified in the book that records all the regulations under the Qing dynasty, known as the Da Qing Hui Dian. These divine beasts are arranged in odd numbers 1-3-5-7-9 on the eaves corners in a clear order as follows: dragon, phœnix, lion, heavenly horse, seahorse, aplustre, fighting bull, suan ni, sea goat, and monkey. Always leading these divine beasts is a figure riding a chicken or phoenix, often called the Prince Min. Nearby is an additional horned beast, the ninth son of the dragon. Each divine beast represents a good omen or virtue and is thus cherished and worshipped. However, there is an exception: the Hall of Supreme Harmony has up to 10 divine beasts on its eaves corners because it is where the emperor holds important ceremonies (such as coronations, weddings, birthdays, year-end celebrations etc.). The use of these divine beasts mainly serves to protect the palaces against evil spirits and to demonstrate the emperor’s power and prestige. Conversely, the Palace of Heavenly Purity, although it is where the emperor works and discusses state affairs with officials, does not have as significant a role as the Hall of Supreme Harmony and therefore only has 9 divine beasts on its eaves corners.

As for the Khôn Ninh palace, seven divine beasts were found on the eaves of the hall because this was the palace of the empress during the Ming dynasty. However, this place was also where the sacrificial rituals to the Tát Mãn religion’s spirits were held, which corresponded to the position of Yin under Yang during the Qing dynasty. It is important to remember that before conquering China, the Qing dynasty was originally Manchu, so they still maintained their own religion.

[The Forbidden City of Beijing (Part 2)]