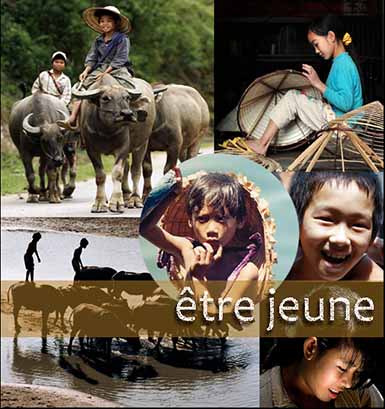

Être jeune

In spite of the war which devastated this country for so many years, the Vietnamese young people continue to crave for life. That amazes enormously those who do not know Vietnam. In this country, » Being Young » concerns always boldness because the living conditions are extremely hard and nature is also extremely rude and pitiless, in particular for those who live in the North and on the Central highlands. It is necessary to know how to resist bravely the forces of nature but it is also necessary to learn how to live with wild creatures, tricking them and fighting them.

One also starts to work very young in Vietnam. From their youth in rural areas, boys tend buffaloes, make them feed on small floodbanks while girls help in the household chores. Very young, from six or seven years old, they know how to cook rice, carry their little brothers, feed the pigs and ducks, carry drinking water to the familiar animals or taking part in family artisanal work. During the years when the war was at its height, young people were also assigned to dig trenches along the small floodbanks to throw themselves in when airplanes approached, live in undergrounds and tunnels to escape the bombings. Girls have twice as much work as boys. It was they who were the first being proposed and sold like slaves or concubines for a few kilos of rice when one could not manage any more to feed a family of several children in the years 30’s and 40’s. Ngô Tất Tố, in his novel » When The Lamp Dies Out « , appeared in 1930, reminds us this reality. To pay a corrupt official, a country-woman had to sell her daughter for one piastre.

Nowadays, even this practice is prohibited, one nevertheless notes a great number of young female prostitutes on the streets of big cities. There, in spite of free education, many of young people must work on little jobs such as selling cigarettes or newspapers, collecting plastic bags etc… , to provide for the subsistence of their families. The living conditions are also distressing. Many young people coming from families afflicted by poverty and war continue to always crawl in tangles of badly erected huts that are dark and terribly dirty. There would be 67000 slums in Saigon at the end of 1994. It is the number maintained by the authorities and published by the press. One still finds the scenes described by novelist Khái Hưng in his work entitled « The Gutters » ( Ðầu Ðường Xó Chợ ) » with pavements and drains encumbered permanently with vegetable peelings, sheets of banana tree leaves and scraps of rags in the poor districts of the big cities.

Facing the indifference of society, novelist Duyên Anh did not hesitate to denounce the indigence of these young people in his novels, among which the most known remains the best-seller « The Hill of The Phantoms« . Inspired by this novel, movie maker Rachid Bouchareb recalled the history of the « Amerasians » who pay the price of the madness of the adults and the war in his film « Dust of Life » in 1994.

In spite of the deficiencies of life, one likes to be young in this country because, if there are no mountains of toys and gifts which submerge our children in the west as Christmas approaches, there are on the other hand popular games, unforgettable memories of childhood. In the countryside, one could go fishing in rice fields and placing hoop nets in the streams to catch shrimps and small fish. One could hunt butterflies and dragonflies with traps made with the stems of bamboo. One could climb trees to seek bird’s nests. Hunting the crickets remained the preferred game of the majority of Vietnamese young people.

While walking in group, ears wide opened for the song of the crickets, eyes scanning the least recesses, one tried to locate the burrows from where came out the song. It is one’s habit to make the insect leave its hole by flooding it with water or dejection, then to lock it up in a matchbox, to make it sing by exciting it with a small feather or to make it drink a little rice alcohol for excitement at the time of cricket fights.

In the cities, one played soccer with bare feet in the middle of the street, the goal posts consisted of stacked clothing. The matches were often stopped by the passage of bicycles. One also played shuttle cock game (Đá Cầu) in the street. The flying object the size of a table tennis ball was made with a fabric end wrapping around a zinc coin. Born in the war, Vietnamese young people did not scorn war games. One manufactured oneself rifles out of cardboard or wood, one fought with swords made of tree branches. One could also fly kites.

This childhood, this youth, all the Vietnamese had it, even novelist Marguerite Duras.

She did not hesistate to point out her Indochinese childhood in her novel « The places« : My brother and I did not spend whole days in the trees but in the woods and on the rivers, on what is called the racs (rạch), these small streams that go down towards the sea. We never put on our shoes, we lived half naked, we bathed in the river.

In this country where the war devastated so much and where thirteen million tons of bombs and sixty million liters of defoliants were poured, being young in the years 60-75 was already a favor of destiny. The young people of Vietnam today no longer know the fear and the hatred of their elders but they continue to have an uncertain future. In spite of that, in their look, there is always a gleam of intense life, a glimmer of hope. It is what is often called » the magic of Vietnamese childhood and youth « .

It is necessary to be young in this country to have such an attachment, an impression always poignant.