Con cóc (The toad)

Version française

Version anglaise

Lúc khai quật tìm kiếm các trống đồng ở miền bắc Việt Nam vào thế kỷ 19 thì các nhà khảo cổ Pháp và Việt tìm thấy trên mặt của vài trống lạị có 4 tượng cóc (hay nhái) được cách điệu và thường đi ngược với kim đồng hồ.Theo sự nhận xét của các nhà khảo cổ đây là các trống đồng có liên quan đến với những nông dân của nền văn hoá trồng lúa nước như người Việt cổ. Con cóc (hay nhái) cũng được thấy thường ở trên trống đồng nhất là thuộc loại Heger 1 thời kỳ muộn (thế kỷ 1 và 2 sau công nguyên). Các nhà khảo cứu người Hoa xem các con cóc (hay nhái) nầy dùng để trang trí cho đẹp mặt trống đồng chớ không có ý nghĩa gì sâu xa cả. Ngược lại, với người dân Việt, sự hiện diện của nó trên mặt trống thì đây là các trống để cầu khẩn thần mưa cho màu mỡ đất đai và thụ hoạt thuận lợi. Theo phong tục của người dân việt thì có sự liên hệ mật thiết giữa các con vật nầy với ông Trời qua câu chuyện cổ tích hóm hỉnh nên mới có câu tục ngữ như sau:

Cóc nhái là cậu ông Trời

Ai mà đánh nó ông Trời đánh cho.

Các con cóc, nhái nầy khi chúng nó kêu lên thì báo hiệu trời sẻ sấp mưa khiến chúng nó trở thành những vật linh thiêng. Chúng được đưa vào thế giới tín ngưỡng của các dân tộc ở miền nam Trung Quốc như đồng bằng Bắc Bộ, Quảng Đông và Quảng Tây và trở thành từ đó một chủ đề riêng: tín ngưỡng thờ động vật. Chúng còn thường được nhắc đến trong các ca dao hay những câu từ ngữ mang ý nghĩa xâu xa như

Ăn cóc bỏ gan, ăn trầu nhả bã

Ăn cơm lừa thóc, ăn cóc bỏ gan

để nói lên sư thận trọng và kinh nghiệm trong việc ăn uống vì gan của cóc có chứa nhiều chất độc.

Cóc còn biểu hiện của cuộc sống tự lập, không dựa vào ai cả.

Con cóc cụt đuôi

Ở bờ ở bụi

Ai nuôi mày lớn ?

Dạ thưa Thầy, con lớn mình ên …

“Mình ên,” tiếng địa phương là một mình, một mình tự kiếm sống và trưởng thành.

Con ếch ám chỉ người dốt nát và có tầm nhìn hiểu biết kém nên mới có câu ca dao dưới đây:

Ếch ngồi đái giếng coi trời đất bằng vung.

cũng như nhà ngụ ngôn Pháp nổi tiếng Jean de la Fontaine khiển trách thậm tệ kẻ khoác lác trong chuyện « Con ếch muốn to bằng con bò ». Chúng ta hay thường nghe nói « Ếch mọc lông nách » để ám chỉ những kẻ tự phụ.

Ếch hay cóc đều là động vât lưỡng cư. Sau khi nở trứng chúng là những con nòng nọc không tay hay chân cho đến khi trưởng thành, chỉ thở bằng mang và nhờ có một cái đuôi mà chúng dùng để bơi như cá. Môt khi trưởng thành, có tứ chi và mất đuôi. Để phân biệt ếch và cóc, động vật lưỡng cư có dáng ngắn, mập với chân nhỏ hơn cơ thể là cóc còn có dáng thanh mảnh với chân dài có khả năng là ếch. Ếch hay thường thích sống trong nước hay thích nhảy trên đất liền còn cóc thì không. Vã lại về kích thước của ếch thì có sự chênh lệch lớn giữa con đực và con cái như ở nước ta loài cái có 10 cm nhưng loài đực chỉ 3-4 cm nên lúc giao phối chúng bám chặc với nhau và di chuyển, đẻ trứng ở những nơi có nước chảy khá mạnh. Trong những năm qua, các nhà khoa học Úc và Việt đã khám phá ra được nhiều loại ếch quá kỳ lạ. Một loài ếch biết bay mới thuộc chi Rhacophorus vừa được phát hiện ở rừng nhiệt đới miền nam Việt Nam, chỉ cách xa thành phố Saigon một trăm cây số. Khả năng bay lượn của Rhacophorus helenae từ cây này sang cây khác đã bảo vệ con ếch bay này tránh khỏi bất cứ thứ gì bò trên mặt đất. Nó sống chủ yếu trên tán cây (canopée). Với đôi chân và bàn tay hình cọ, nó bơi và bay trong không khí theo lời tường thuật của nhà sinh học Úc Jodi Rowley. Còn có một loại khác được phát hiện tại khu bảo tồn thiên nhiên Pu Hoat, loài mới này được gọi là Gracixalus Quangi, sống trong rừng ở độ cao từ 600 đến 1300 mét. Loai nầy nó biết hót như chim chớ không phải quạ quạ như các loại ếch khác và nó có nhiều tiếng kêu khác nhau.

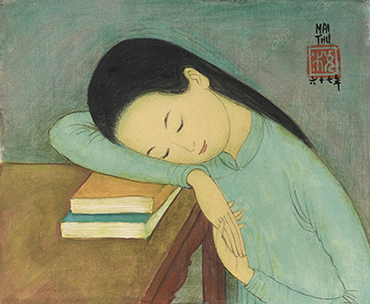

Chử oa 蛙 trong tiếng nôm ta dùng chỉ con ếch và nhái. Còn cóc thì ta gọi là thiềm thừ 蟾蜍 được nói nhiều trong phong thủy. Còn các tranh Đông Hồ thì có một tấm tranh được gọi là thầy đồ cóc. Trên tranh có dòng chữ « Lão Oa độc giảng« , có nghĩa là ông Ếch một mình giảng dạy. Đáng lý ra phải nói Ếch nhưng trong dân gian không quen phân biệt nên gọi Cóc nhất là hình con cóc thể hiện trên trống đồng và trên các đồ vật thời Đồng Sơn vã lại còn là cậu ông Trời. Ngụ ý của bức tranh không phải dùng để chỉ là thầy cóc đang ngồi dạy học mà muốn nhắc nhở cho hậu thế biết dân ta từ ngày xưa có chữ khoa đẩu, một loại chữ ấy giống như con nòng nọc có đầu lớn, đuôi nhỏ.Vi vậy trong tranh dù chỉ có hiện diện của các sinh vật nhưng chúng nó có những hành động như con người. Có lẽ nghệ nhân khi vẽ tấm tranh muốn nhắn nhủ điều gì cho hậu thế biết dân tộc ta cũng có chữ viết và nên nhớ về cội nguồn của dân tộc. Vì là chữ giống như con nòng nọc nên mới biến người thành ếch vì ếch là mẹ của con nòng nọc.

Nhắc đến chữ Oa củng nên nhắc đến chuyến công du của sứ thần Mạc Đĩnh Chi khi lúc ông sang Tàu dưới thời ngự trị của vua Nguyên Thế Tổ (Kubilai Khan). Ông được vua Nguyên Thế Tổ công nhận tài năng của ông và trao cho ông danh hiệu « Trạng Nguyên đầu tiên » (Lưỡng Quốc Trạng Nguyên) ở cả Trung Hoa và Việt Nam, khiến một số quan lại ganh tị. Một trong số người nầy cố tình làm bẽ mặt ông ta vào một buổi sáng đẹp trời bằng cách ví ông ta như một con chim bởi vì âm điệu đơn âm của ngôn ngữ, người dân Việt khi họ nói cho cảm giác người nghe như họ luôn luôn hót líu lo:

Quích tập chi đầu đàm Lỗ luận: tri tri vi tri chi, bất tri vi bất tri, thị tri

Chim đậu cành đọc sách Lỗ luận: biết thì báo là biết, chẳng biết thì báo chẳng biết, ấy là biết đó.

Đây là một cách để khuyên Mạc Ðỉnh Chi nên khiêm tốn hơn và cư xử như một người đàn ông có phẩm chất Nho giáo (Junzi). Mạc Đỉnh Chi trả lời bằng cách ví anh nầy như một con ếch. Người Trung Hoa thường có thói nói to và tóp tép lưỡi qua tư cách họ uống rượu.

Oa minh trì thượng đọc Châu Thư: lạc dữ đọc lạc nhạc, lạc dữ chúng lạc nhạc, thục lạc.

Châu chuộc trên ao đọc sách Châu Thu: cùng ít người vui nhạc, cùng nhiều người vui nhạc, đằng nào vui hơn.

Đó là một cách để nói lại với người quan lại nầy nên có một tâm trí lành mạnh để hành xử một cách công bằng và phân biệt nghiêm chỉnh.

Theo đặc tính của đại tộc Bách Việt mà trong đó có tộc Lạc Việt thì các tộc nầy thích ăn sò hến và ếch. Chưa kể số lượng ếch dùng ở trong nước nhưng được biết ngày nay từ 2010–2019 Việt Nam đã cung cấp cho EU hơn 8400 tấn đùi ếch, trở thành nhà cung cấp đùi ếch lớn thứ hai sau Nam Dương vào EU (theo tin Tia Sáng). Pháp nhập khẩu hơn 2.500 tấn đùi ếch từ nước ngoài mỗi năm để đáp ứng nhu cầu trong nước. Nhu cầu lên cao tại châu Âu đang gây rắc rối lớn cho các nước cung cấp vì không biết có bao nhiêu con ếch được xuất khẩu trong các trại nuôi ếch và bao nhiêu con còn lại trong tự nhiên.

Đây là mối lo ngại lớn nhất của các nhà sinh học hiện nay vì ếch giữ một vai trò cực kỳ quan trọng trong chuỗi thức ăn. Ếch vừa là thợ săn mà vừa là con mồi. Nhờ có ếch mà số lượng châu chấu và muỗi được giảm. Ếch là thuốc trừ sâu tự nhiên. Nếu ngày nào không còn ếch thì phải dùng thuốc trừ sâu nhiều hơn thì có hại cho sức khoẻ và môi trường. Theo cơ quan Humance Society International, số lượng ếch ở Việt Nam đã giảm đáng kể trong những thập kỷ gần đây vì nó cũng là con mồi của con người. Nó không những là nguồn lợi đáng kể trong việc xuất khẩu mà còn là món ăn dân dã ở nước ta nhất là thịt nó thơm như thịt gà nên được gọi là gà đồng. Chổ nào có nước có sông ngòi là có sự hiện diện của ếch thì có các món đặc sản từ ếch như đùi ếch chiên giòn, ếch xào măng, ếch nấu cà ri, ếch xào chua ngọt, ếch xào xã ớt vân vân.

Ở miền tây Nam Bộ, vào cuối tháng 8, lúc mùa nước nổi hay thường có thú vui giải trí là trò đi câu hay soi bắt ếch. Lũ ếch thường tụ hợp ở những nơi có nhiều côn trùng và sâu bọ. Chỉ cần có cây trúc dài khoảng bốn năm mét, cước dài với mồi rồi thả mồi xuống các hang hay các vùng trũng nước. Khi có tiếng động thì phải nhanh tay giật mạnh cái cần trúc lên bờ vì ếch đã cắn câu. Đây là thú điền viên, một nghệ thuật câu ếch tinh vi và nhanh nhẹn của những đứa trẻ sống ở miền tây. Còn soi ếch cần tránh làm ồn ào lúc trời lại tối và dùng đèn pin soi vào mắt ếch thì nó lại ngồi im lìm trên bờ không di chuyển còn không khi nghe tiếng động, nó biến mất nhanh nhẹn dưới nước liền theo lời tường thuật của những kẻ rành đi bắt ếch đồng.

Lors de fouilles de tambours de bronze dans le nord du Vietnam au XIXème siècle, des archéologues français et vietnamiens ont découvert sur les faces de certains tambours de bronze quatre crapauds stylisés (ou grenouilles) se déplaçant souvent dans le sens inverse des aiguilles d’une montre. Selon les archéologues ces tambours en bronze sont liés étroitement aux agriculteurs de la culture du riz inondé comme les Proto-Vietnamiens. Les crapauds (ou grenouilles) sont également fréquemment trouvés sur les tambours de bronze, en particulier ceux du type Heger 1 tardif (1er et 2ème siècles après J.-C.). Les chercheurs chinois considèrent que ces crapauds (ou grenouilles) sont utilisés pour décorer les tambours de bronze et n’ont aucune signification particulière. Au contraire, pour le peuple vietnamien, leur présence sur la surface du tambour a pour but d’implorer le génie de la pluie de rendre les terres plus fertiles et des récoltes fructueuses. Selon la coutume vietnamienne, il existe évidemment un lien étroit entre ces amphibiens et Dieu à travers un conte humoristique. C’est pourquoi on a le proverbe suivant :

Le crapaud (ou grenouille) est l’oncle maternel de Dieu.

Celui qui ose le battre, Dieu le battra.

Lorsque ces crapauds et ces grenouilles coassent, ils signalent qu’il est sur le point de pleuvoir, ce qui les rend en fait des animaux sacrés. Ils ont été introduits dans le monde religieux des peuples vivant au sud de la Chine comme ceux du delta de Tonkin, du Guangdong et du Guangxi et ils sont devenus désormais un sujet à part entière dans le culte des animaux. Ils sont souvent mentionnés dans des chansons folkloriques ou des expressions ayant des significations profondes.

Ăn cóc bỏ gan, ăn trầu nhả bã

Ăn cơm lừa thóc, ăn cóc bỏ gan

Lorsqu’on mange une grenouille, il faut jeter son foie. Lorsqu’on chique le bétel, il faut cracher les résidus ;

Lorsqu’on mange du riz, il faut rejeter les cosses de riz. Lorsqu’on mange une grenouille, il faut jeter son foie.

Ce sont des expressions notant la prudence et l’expérience en matière de consommation car le foie d’un crapaud contient de nombreuses substances toxiques.

Le crapaud est la représentation d’une vie indépendante et n’ayant pas besoin de l’aide de personne.

Con cóc cụt đuôi

Ở bờ ở bụi

Ai nuôi mày lớn ?

Dạ thưa Thầy, con lớn mình ên

Crapaud sans queue,

Tu vis au bord du rivage et dans le ruisseau

Qui t’a élevé ?

Oui monsieur, je grandis tout seul.

La grenouille incarne souvent un ignorant et a une vision assez étroite et limitée. Il y a donc un proverbe ci-dessous:

Ếch ngồi đái giếng coi trời đất bằng vung.

La grenouille assise au fond d’un puits considère le ciel comme un couvercle.

comme le célèbre fabuliste français Jean de la Fontaine a l’ occasion de réprimander le vantard dans l’histoire « La grenouille veut être aussi grosse que le bœuf ». On entend souvent l’expression Ếch mọc lông nách « grenouille qui prétend avoir des poils sous les aisselles » pour désigner les personnes vaniteuses.

Les grenouilles et les crapauds sont tous deux des amphibiens. Après l’éclosion, ils sont des têtards sans bras ni jambes jusqu’à l’âge adulte, respirant uniquement grâce à des branchies et une queue qui leur permet de nager comme des poissons. Une fois adulte, il possède quatre membres et perd sa queue. Pour distinguer les grenouilles des crapauds, les amphibiens au corps court et gras et aux pattes plus petites que leur corps sont des crapauds, tandis que ceux au corps mince et aux pattes longues sont probablement des grenouilles. Ces dernières aiment généralement vivre dans l’eau ou sauter sur terre, mais pas les crapauds. De plus, il existe une grande différence dans la taille des grenouilles entre les mâles et les femelles. Dans notre pays, les femelles mesurent 10 cm de long, mais les mâles n’ont que 3 à 4 cm. Ainsi, lors de l’accouplement, elles s’accrochent les unes aux autres dans leur déplacement et pondent leurs œufs dans des endroits à fort courant d’eau. Au fil des années, les scientifiques australiens et vietnamiens ont découvert de nombreuses espèces étranges de grenouilles. Une nouvelle espèce de grenouille volante appartenant au genre Rhacophorus vient d’être découverte dans les forêts tropicales du sud du Vietnam, seulement à cent kilomètres de la ville de Saigon. La capacité de Rhacophorus helenae de planer d’arbre en arbre protège cette grenouille volante de tout ce qui rampe sur le sol. Il vit principalement dans la canopée. Dotée de pattes et de mains en forme de paume, elle nage et vole dans les airs, selon la biologiste australienne Jodi Rowley. Une autre espèce a été découverte dans la réserve naturelle de Pu Hoat. Cette nouvelle espèce s’appelle Gracixalus Quangi, vivant dans les forêts à des altitudes de 600 à 1300 mètres. Cette espèce peut chanter également comme un oiseau. Contrairement au corbeau et aux autres grenouilles elle possède de nombreux cris différents.

Dans la langue Nôm le mot « oa » est utilisé pour désigner les grenouilles et les crapauds. Quant au crapaud, on l’appelle « Thiêm thù » 蟾蜍 et il est souvent mentionné en feng shui. En ce qui concerne les estampes de Đông Hồ, il existe un tableau intitulé « L’érudit crapaud » sur lequel il y a la ligne «Lão Oa độc giảng», ce qui signifie que le vieux crapaud enseigne seul. Normalement on devrait l’appeler « Grenouille ». Comme les gens ne sont pas habitués à faire la distinction, ils l’appellent Crapaud quand même du fait que le crapaud figure sur les tambours de bronze et sur les artefacts de la période de Đồng Sơn et qu’il est aussi l’oncle maternel de Dieu. La signification du tableau n’est pas dans l’intention de montrer le crapaud professeur assis et enseignant, mais de rappeler aux générations futures que notre peuple possédait l’écriture Khoa Đẩu dans le passé, un type d’écriture ressemblant à un têtard avec une grosse tête et une petite queue. Ainsi, bien qu’il n’y ait que des créatures présentes dans le tableau, celles-ci agissent comme les humains. Peut-être au moment de la réalisation de ce tableau, l’artiste voulait dire aux générations futures que notre peuple possédait aussi une langue écrite et qu’il devrait s’en souvenir. Comme la lettre ressemblait à un têtard, il voulait transformer les gens en grenouilles car ces dernières étaient la mère des têtards.

En mentionnant le mot Oa, nous devons évoquer également le voyage de l’ambassadeur Mạc Đỉnh Chi lorsqu’il se rendit en Chine sous le règne du roi Nguyên Thế Tổ (Kubilai Khan). Ce dernier dut reconnaître son talent et lui accorda ainsi le titre » Premier docteur » ( Lưỡng Quốc Trạng Nguyên ) aussi bien en Chine qu’au Viêt-Nam, ce qui rendit jaloux quelques mandarins chinois. L’un d’eux tenta de l’humilier un beau matin en le traitant comme un oiseau car à cause de la tonalité monosyllabique de la langue, les Vietnamiens donnent l’impression de gazouiller toujours lorsqu’ils parlent:

Quích tập chi đầu đàm Lỗ luận: tri tri vi tri chi, bất tri vi bất tri, thị tri

Chim đậu cành đọc sách Lỗ luận: biết thì báo là biết, chẳng biết thì báo chảng biết, ấy là biết đó.

L’oiseau s’agrippant sur une branche lit ce qui a été écrit dans le livre Les Entretiens : Si nous savons quelque chose, nous disons que nous la savons. Dans le cas contraire, nous disons que nous ne la savons pas. C’est ainsi que nous disons que nous savons quelque chose.

C’est une façon de recommander Mạc Ðỉnh Chi de se montrer plus humble et de se comporter comme un homme de qualité confucéenne ( junzi ). Mạc Ðỉnh Chi lui répliqua en le traitant comme une grenouille car les Chinois ont l’habitude de clapper à cause de leur manière de boire ou de parler bruyamment:

Oa minh trì thượng đọc Châu Thư: lạc dữ đọc lạc nhạc, lạc dữ chúng lạc nhạc, thục lạc.

Châu chuộc trên ao đọc sách Châu Thu: cùng ít người vui nhạc, cùng nhiều người vui nhạc, đằng nào vui hơn.

La grenouille barbotant dans la mare lit ce qui a été écrit dans le livre Livre des Documents Historiques (Chou Ching): certains jouent seuls de la trompette, d’autres jouent ensemble de la trompette. Lesquels paraissent en jouer mieux.

C’est une façon de dire au mandarin chinois d’avoir un esprit sain pour pouvoir avoir un comportement juste et un discernement équitable.

Selon les caractéristiques des Bai Yue dont fait partie la tribu Lo Yue, ils aiment manger des palourdes et des grenouilles. Sans parler du nombre de grenouilles consommées dans le pays, on sait qu’entre 2010 et 2019, le Vietnam a fourni à l’UE plus de 8 400 tonnes de cuisses de grenouilles. Il devient ainsi le deuxième grand fournisseur de cuisses de grenouilles après l’Indonésie à l’UE (selon le journal Tia Sáng). La France importe chaque année plus de 2 500 tonnes de cuisses de grenouilles de l’étranger pour répondre à sa consommation interne. La forte demande en Europe pose de gros problèmes aux pays fournisseurs car on ne sait pas combien de grenouilles exportées des fermes d’élevage et combien de grenouilles prises dans la nature.

C’est la plus grande préoccupation des biologistes d’aujourd’hui, car les grenouilles jouent un rôle extrêmement important dans la chaîne alimentaire. Les grenouilles sont à la fois des chasseurs et des proies. Grâce aux grenouilles, le nombre de criquets et de moustiques est réduit. Les grenouilles sont des « pesticides naturels ». S’il n’y a plus de grenouilles, nous devrons utiliser davantage de pesticides, ce qui est nocif pour la santé et l’environnement. Selon la Humance Society International, le nombre de grenouilles au Vietnam a considérablement diminué au cours des dernières décennies, car elles sont également la proie des humains. Ce n’est pas seulement une source importante d’exportation mais c’est aussi une spécialité populaire dans notre pays, en particulier sa chair parfumée comme celle du poulet. C’est pourquoi on appelle la grenouille avec le vocable « poulet des champs ».

Partout où il y a de l’eau et des rivières, il y a des grenouilles. Il existe donc des spécialités locales de grenouilles telles que les cuisses de grenouilles frites, les cuisses de grenouilles sautées aux pousses de bambou, les cuisses de grenouilles au curry, les cuisses de grenouilles sautées aigre-douce, les grenouilles sautées à la citronnelle et au piment etc.

Dans la région du sud-ouest du Viet Nam, à la fin du mois d’août, durant la saison des inondations, les gens aiment aller pêcher ou attraper des grenouilles. Celles-ci se rassemblent souvent dans des endroits où il y a beaucoup d’insectes et de bestioles. Il suffit d’avoir un bâton de bambou d’environ quatre à cinq mètres de long, muni d’une longue ligne avec un appât et de déposer le tout dans des grottes ou des zones basses. Lorsqu’il y a du bruit, il faut rapidement tirer la perche en bambou jusqu’au rivage car la grenouille a mordu à l’hameçon. Il s’agit bien d’un passe-temps rural, un art de pêche à la grenouille sophistiqué et agile des enfants vivant dans l’ouest du Vietnam. Pour attraper les grenouilles, on doit devez éviter de faire du bruit. Lorsqu’il fait sombre la nuit, on doit se servir d’une lampe de poche pour éblouir les yeux de la grenouille. Celle-ci reste « tétanisée » et immobile sur le rivage sinon en cas de bruit, elle disparaîtra rapidement sous l’eau selon les gens qui sont habitués à attraper les grenouilles.

Version anglaise

During excavations of bronze drums in northern Vietnam in the 19th century, French and Vietnamese archaeologists discovered four stylized toads (or frogs) on the faces of some bronze drums, often moving counterclockwise. According to archaeologists, these bronze drums are closely related to flooded rice farmers such as the Proto-Vietnamese. Toads (or frogs) are also frequently found on bronze drums, especially those of the late Heger 1 type (1st and 2nd centuries A.D.). Chinese researchers consider these toads (or frogs) to be used to decorate bronze drums and have no particular significance. On the contrary, for the Vietnamese people, their presence on the drum surface is intended to implore the rain spirit to make the land more fertile and harvests fruitful. According to Vietnamese custom, there is obviously a close connection between these amphibians and God through a humorous tale. This is why we have the following proverb:

The toad (or frog) is God’s maternal uncle.

Whoever dares to beat him, God will beat him.

When these toads and frogs croak, they signal that it is about to rain, which actually makes them sacred animals. They were introduced into the religious world of people living in southern China such as those in the Tonkin Delta, Guangdong, and Guangxi, and have now become a separate subject in animal worship. They are often mentioned in folk songs or expressions with deep meanings.

Ăn cóc bỏ gan, ăn trầu nhả bã

Ăn cơm lừa thóc, ăn cóc bỏ gan.

When you eat a frog, you must discard its liver. When you chew betel, you must spit out the residue;

When you eat rice, you must discard the rice husks. When you eat a frog, you must discard its liver.

These are expressions that denote caution and experience when consuming food, as a toad’s liver contains many toxic substances.

The toad represents an independent life that requires no help from anyone.

Con cóc cụt đuôi

Ở bờ ở bụi

Ai nuôi mày lớn ?

Dạ thưa Thầy, con lớn mình ên.

Tailless toad,

You live by the shore and in the bush.

Who raised you?

Yes sir, I’m growing up all alone.

The frog often embodies an ignoramus and has a rather short and limited vision. Therefore, there is a proverb below:

Ếch ngồi đái giếng coi trời đất bằng vung.

The frog sitting at the bottom of a well considers the sky as a lid.

as the famous French fabulist Jean de la Fontaine has occasion to reprimand the boaster in the story « The frog wants to be as big as the ox. » We often hear the expression Ếch mọc lông nách « frog who claims to have hair under his armpits » to refer to vain people.

Frogs and toads are both amphibians. After hatching, they are tadpoles without arms or legs until adulthood, breathing only through gills and a tail that allows them to swim like fish. Once adult, it has four limbs and loses its tail. To distinguish frogs from toads, amphibians with short, fat bodies and legs smaller than their bodies are toads, while those with thin bodies and long legs are probably frogs. The latter generally like to live in water or hop on land, but toads do not. Furthermore, there is a large difference in the size of frogs between males and females.

In our country, females are 10 cm long, but males are only 3 to 4 cm. Therefore, during mating, they cling to each other as they move and lay their eggs in places with strong water currents. Over the years, Australian and Vietnamese scientists have discovered many strange species of frogs. A new species of flying frog belonging to the genus Rhacophorus has just been discovered in the tropical forests of southern Vietnam, just 100 kilometers from the city of Saigon. Rhacophorus helenae’s ability to glide from tree to tree protects this flying frog from anything crawling on the ground. It lives primarily in the canopy. Equipped with palm-like legs and hands, it swims and flies through the air, according to Australian biologist Jodi Rowley. Another species has been discovered in the Pu Hoat Nature Reserve. This new species is called Gracixalus quangi, which lives in forests at altitudes of 600 to 1300 meters. This species can also sing like a bird. Unlike the crow and other frogs, it has many different calls.

In the Nôm language, the word « oa » is used to refer to both frogs and toads. The toad is called « Thiem thù » (蟾蜍) and is often mentioned in feng shui. Regarding Dong Ho’s prints, there is a painting titled « The Scholarly Toad » with the line « Lão Oa độc giảng, » which means that the old toad teaches alone. Normally, he should be called « Frog. » Since people are not used to making the distinction, they call him Toad anyway, because the toad appears on bronze drums and artifacts from the Dong Son period and he is also the maternal uncle of God. The meaning of the painting is not to show the toad teacher sitting and teaching, but to remind future generations that our people had Khoa Đẩu writing in the past, a type of writing resembling a tadpole with a big head and a small tail. Thus, although there are only creatures present in the painting, they act like humans. Perhaps at the time of making this painting, the artist wanted to tell future generations that our people also had a written language and should remember it. Since the letter resembled a tadpole, he wanted to turn people into frogs because frogs were the mother of tadpoles.

Mentioning the word Oa, we must also mention the journey of Ambassador Mạc Đỉnh Chi when he went to China during the reign of King Kubilai Khan. The latter recognized his talent and thus granted him the title of « First Doctor » (Lưỡng Quốc Trạng Nguyên) both in China and in Vietnam, which made some Chinese mandarins jealous. One of them tried to humiliate him one fine morning by treating him like a bird because due to the monosyllabic tone of the language, the Vietnamese give the impression of always chirping when they speak:

Quích tập chi đầu đàm Lỗ luận: tri tri vi tri chi, bất tri vi bất tri, thị tri

Chim đậu cành đọc sách Lỗ luận: biết thì báo là biết, chẳng biết thì báo chảng biết, ấy là biết đó.

The bird clinging to a branch reads what was written in the book « The Conversations »: If we know something, we say that we know it. If we don’t, we say that we don’t know it. This is how we say that we know something.

This is a way of recommending Mạc Ðỉnh Chi to be more humble and to behave like a man of Confucian quality (junzi). Mạc Ðỉnh Chi replied by treating him like a frog because the Chinese have the habit of clapping because of their way of drinking or speaking loudly:

Oa minh trì thượng đọc Châu Thư: lạc dữ đọc lạc nhạc, lạc dữ chúng lạc nhạc, thục lạc.

Châu chuộc trên ao đọc sách Châu Thu: cùng ít người vui nhạc, cùng nhiều người vui nhạc, đằng nào vui hơn.

The frog splashing in the pond reads what was written in the Book of Historical Documents (Chou Ching): some play the trumpet alone, others play the trumpet together. Which one seems to play it better?

This is a way of telling the Chinese Mandarin to have a sound mind so as to be able to behave justly and discern justly.

According to the Bai Yue people, who include the Lo Yue tribe, they enjoy eating clams and frogs. Not to mention the number of frogs consumed in the country, it is known that between 2010 and 2019, Vietnam supplied the EU with more than 8,400 tons of frog legs. This makes it the second largest supplier of frog legs to the EU after Indonesia (according to the Tia Sáng newspaper). France imports more than 2,500 tons of frog legs from abroad each year to meet its domestic consumption. The high demand in Europe poses major problems for supplying countries because it is unclear how many frogs are exported from breeding farms and how many are taken from the wild.

This is the biggest concern of biologists today because frogs play an extremely important role in the food chain. Frogs are both hunters and prey. Thanks to frogs, the number of locusts and mosquitoes is reduced. Frogs are « natural pesticides. » If there are no more frogs, we will have to use more pesticides, which is harmful to health and the environment. According to the Humance Society International, the number of frogs in Vietnam has decreased significantly in recent decades because they are also preyed on by humans. It is not only an important source of export but also a popular specialty in our country, especially its fragrant meat like that of chicken. That is why the frog is called « field chicken. »

Wherever there is water and rivers, there are frogs. Therefore, there are local frog specialties such as fried frog legs, stir-fried frog legs with bamboo shoots, curry frog legs, sweet and sour stir-fried frog legs, stir-fried frog legs with lemongrass and chili etc. In the southwest region of Vietnam, at the end of August, during the flood season, people like to go fishing or catching frogs. These often gather in places where there are many insects and creatures. All you need is a bamboo stick about four to five meters long, equipped with a long line with bait, and drop it into caves or low-lying areas. When there is noise, you must quickly pull the bamboo pole to the shore because the frog has taken the bait. This is indeed a rural pastime, a sophisticated and agile frog fishing art of children living in western Vietnam. To catch frogs, you must avoid making noise. When it is dark at night, you must use a flashlight to dazzle the frog’s eyes. This one remains « frozen » and motionless on the shore otherwise in case of noise, it will quickly disappear underwater according to people who are used to catching frogs.

[Return RELIGION]

Tình nào

Tình nào