Version française

Version vietnamienne

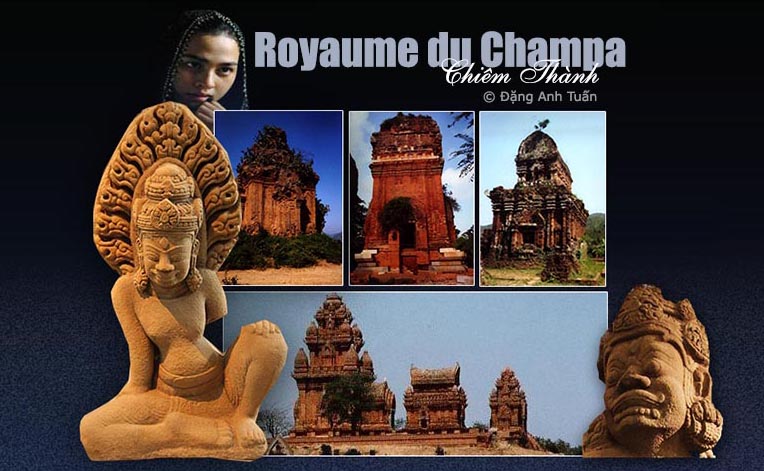

Until now, one does not known precisely the ethnic origin of Cham people. Some believe that they came from the Asian mainland and were deported with the other populations living in the south of China (the Bai Yue) by the Chinese while others (ethnologists, anthropologists linguists) highlighted the insular origin through their research studies.

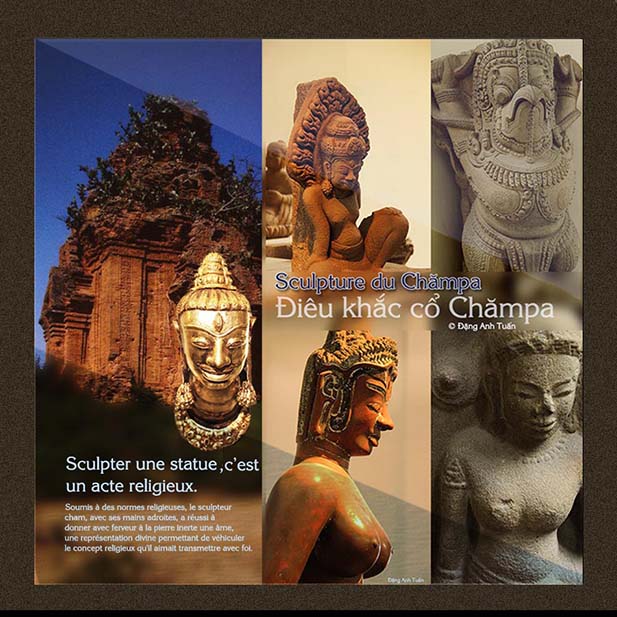

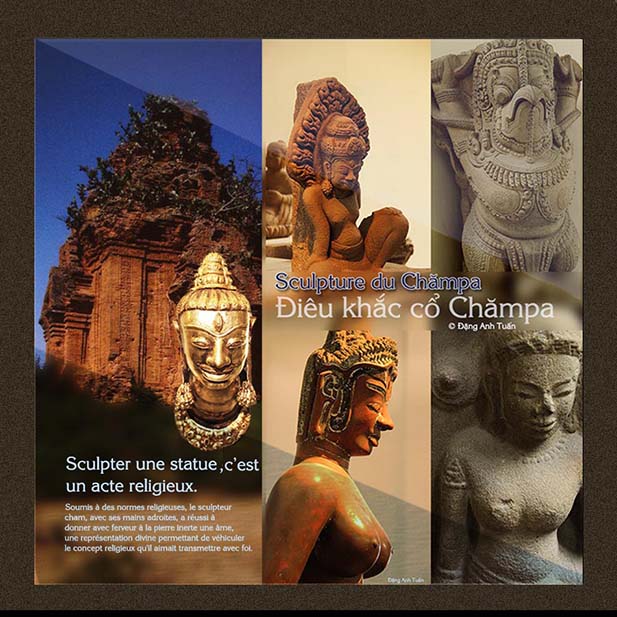

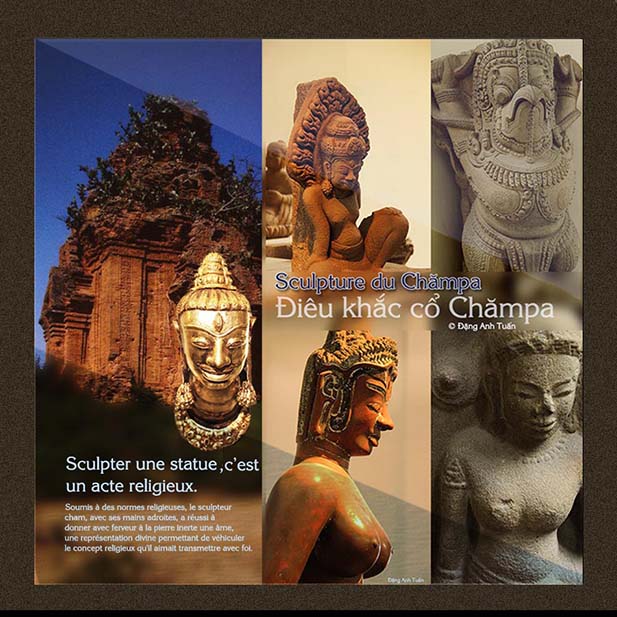

To sculpt a statue, it is a religious act

For these latter, the Cham were probably the people living in the Southern Ocean (archipelagic countries or that of Malaysian Peninsula).,At the legendary era, the Champa oral traditions speaking of the linkage between Chămpa and Java, consolidate this latter hypothesis.

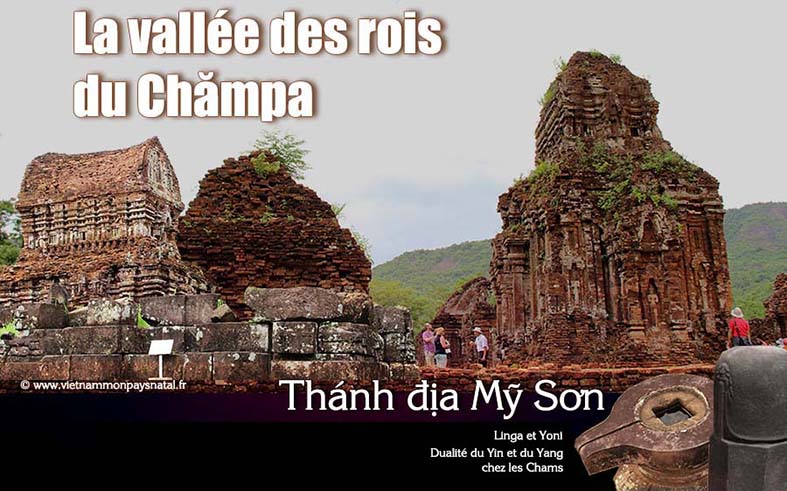

Known as Vikings from Southeast Asia, Champa people lived along the coasts of center and south of Vietnam today. Their main activities were essentially based on trade. They were in contact very early with China and territories as far away as Malaysian peninsula, perhaps the coasts of South India.

Being devoted to religious purposes, the Champa sculpture thus did not escape political recupercussions and influences from outside, in particular those of India, Cambodia and Java. These ones thus became the main forces in creation, development and evolution of styles for their art. For French researcher Jean Boisselier, the Champa sculpture was very closely with the history. Significant changes have been highlighted in the development of Champa sculpture, in particular the statuary with historical events, dynastic changes or relations that Champa have had with its neighbouring countries (Vietnam or Cambodia). Thanks to vietnamese researcher Ngô văn Doanh, each time an important incidence came from outside, one did not take long to see the emergence of a new style in Chămpa sculpture. To achieve this, it is sufficient to cite an example: to 11th-12th century, the intensification of violent contacts, especially with Vietnam and Cambodia and the emergence of new conceptions in relation to the foundations of royal power, can explain the originality and richness found in Tháp Mắm style.

Pictures gallery

Being the expression of the Indian pantheon (brahmaniste but especially shivaiste and Buddhist), the Cham sculpture resort to local interpretation of the concepts with elegance rather than slavish imitation. Above all, it is a support for meditation and a proof of devotion. « To sculpt a statue », it is a religious act. Being subject to religious norms, the Cham sculptor, with his skillful hands, has succeeded in giving, with fervour, to inert stone a soul, a divine representation enabling to convey the religious concept he loved to transmit with faith. The Cham sculpture is peaceful. No scene of horror is present. There are only animal creatures slightly fanciful (lions, dragons, birds, elephants etc. . ). One could find no violent and decent form in the deities. Despite the evolution of styles throughout history, the Cham sculpture continues to keep the same divine and animal creatures in a constant theme.

Makara

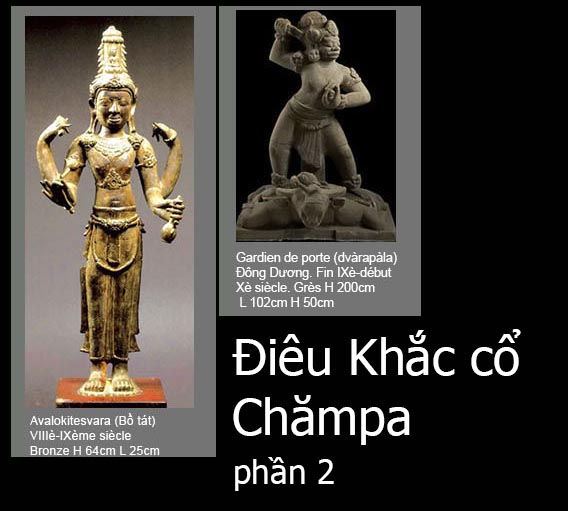

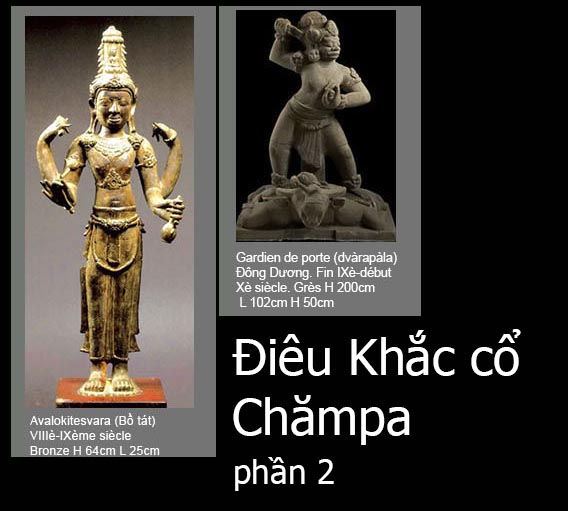

The Cham art manages to keep its specificity, its facial own expression and its particular beauty without being not a slavish imitation from external models and affecting its singularity in the Hindu sculpture found in India and Southeast Asia. In spite of lack of animation and realism, Cham artworks are predominantly carved in sandstone and much more rarely in terracotta and other alloys (gold, silver, bronze etc. .. ).

Generally speaking, being in the modest dimension, they relate religious beliefs and conceptions of the world. They cannot leave us impassive because they always give us a very strange impression. It is one of the features of the beauty in the Cham art.

One finds sculptures in the round, high-reliefs and bas-reliefs in the Cham art. A « rond-bosse » is a scuplture around which we can turn to see the sculptor work . A high-relief is a sculpture having a relief very salient and it does not untie itself from the background. As for low-relief, it is a sculpture with a relief less salient on a uniform background. In the Cham sculpture, one retains the trend toward the adoption of the creatures roundness at the level of the reliefs. Few scenes are included in this sculpture. The lack of continuity or awarkness are noted at the assembly level in the opposite case.

The creatures found in the Cham sculpture tend to be always detached from space that surrounds them with brilliance. They have something monumental. Even in the case where they are grouped together (in the artworks of Mỹ Sơn, Trà Kiệu chronicling the Cham daily life ), they give us the impression that each one remains independently from others.

One can say that the Cham sculptor is solely interested by creature he wants to show and glorify without thinking at no time to details and imperfections becoming excessively unrealistic (hand too big or Trà Kiệu dancer arm too flexed for example) and without the perfect imitation in Hindu original models, which gives to Cham sculpture the character « monumental » not found in the other sculptures. It is an another feature found in this Cham sculpture.

The artworks are limited but they testify to a plastic beautiful quality and the expression of various religions. It is difficult to give them a same style. By contrast, some features are closely linked to tradition of Amaravati Indian art . It is only in the second half of 7th century that under the reign of Prakasadharma Vikrantavarman I king , the Champa sculpture began to take body and to reveal its originality. More reading

- Mỹ Sơn E1 style: (7th -middle 8th century)

- (Middle 8th- middle 9th century). Hoàn Vương period

- Ðồng Dương style (9th -10th century)

- Mỹ Sơn A 1 style (10 th century)

- Tháp Mắm style (or Bình Ðịnh style)

- Yang Mum and Pô Rome style ( 14th -15tn century)