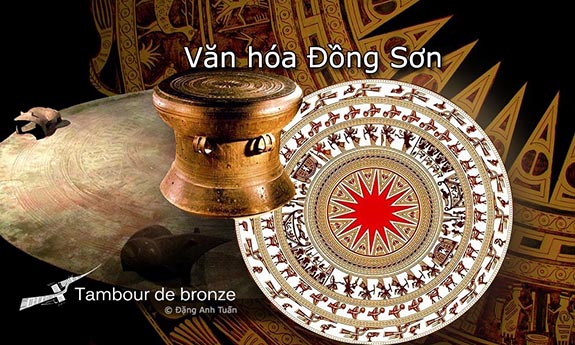

Who are the Dongsonians?

Version française

Version vietnamienne

It is very important to know them because we know they were the owners of these bronze drums. Are they the ancestors of the current Vietnamese? Very little is known about these people and their culture because the research started in the early 20th century by the French was interrupted during the long years of war that Vietnam experienced. However, it is certain that in the 1st century AD, the Dongsonian culture ended with the Chinese annexation.

It was only from 1980 that archaeological excavations resumed. We began to better understand their origin, way of life, and sphere of influence. Thanks to the exceptionally enriched archaeological documentation in recent years, the origin of the Dongsonian culture has been fairly clarified. This culture has its roots among the pre-Dongsonian cultures (those of Phùng Nguyên, Ðồng Dậu, and Gò Mun). There is no need to look so far north or west for the origin of this culture. The Dongsonian culture is actually the result of a succession of stages corresponding to these three cultures mentioned above in a continuous cultural development. The eminent Vietnamese archaeologist Hà Văn Tấn was right to solemnly say: To search for the origins of the Dongsonian culture in the North or West, as several researchers did in the past, is to put forward a hypothesis without scientific basis.

Thanks to the distribution maps of archaeological sites in the Red River basin, it is evident that the pre-Dongson Bronze Age cultures occupied exactly the same region where the sites of the Phùng Nguyên culture were located. It can be said without hesitation that the Đông Sơn culture extends from Hoàng Liên Sơn province in the north to Bình Trị Thiên province in the south.

The Dongsonians were above all skilled rice farmers. They cultivated rice using slash-and-burn methods and flooded fields. They raised buffaloes and pigs. But it was water that was both their wealth and their primary concern because it could be deadly, overflowing from the Red River to engulf crops. They were daring navigators, so close to rivers and coasts that they were accustomed to using dugout canoes for their movements. This custom was so deeply ingrained in their minds that they built their homes as wooden stilt houses with immense roofs curved at both ends, decorated with totemic birds and resembling a dugout canoe.

Even in their death, they designed coffins shaped like canoes. According to Trịnh Cao Tường, a specialist in the study of communal houses (đình) of Vietnamese villages, the architecture of the Vietnamese communal house elevated on stilts reflects the echo of the spirit of the Dongsonians still present in the daily life of the Vietnamese.

The Dongsonians used to tattoo their bodies, chew a preparation made from areca nuts, and blacken their teeth. Tattooing, often described as a « barbaric » practice in Chinese annals, was, according to Vietnamese texts, intended to protect people from attacks by water dragons (con thuồng luồng).

The habit of chewing betel is very ancient in Vietnam. It existed long before the Chinese conquest. When mentioning the blackening of teeth, one cannot forget the famous phrase spoken by Emperor Quang Trung before the liberation of the capital « Thăng Long, » occupied by the Qing: « Đánh để được giữ răng đen. » Fight the Chinese to liberate the city and to keep the teeth blackened. This clearly shows his political will to perpetuate Vietnamese culture, particularly that of the Dongsonians.

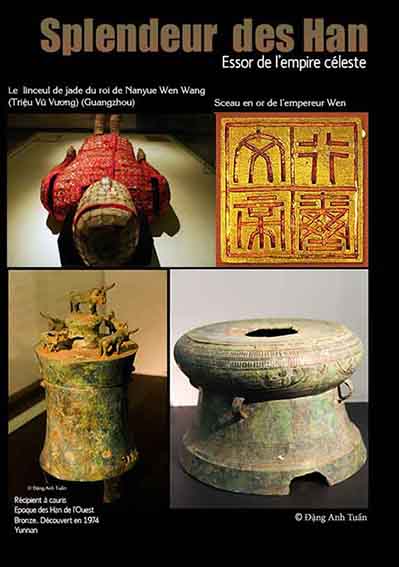

They wore their hair long in a bun and supported by a turban. According to some Vietnamese texts, they had short hair to facilitate their movement in the mountain forests. Their clothing was made from plant fibers. During recent excavations of the Làng Cả necropolis (Việt Trì) in 1977 and 1978, it was observed that differences in wealth were pronounced among the Dongsonians in the analysis of funerary furniture. Opulence is visible in certain individual tombs. Society began to structure itself in a way that revealed the gap between the rich and the poor through funerary furniture. There is no longer any doubt about the increasingly advanced hierarchy in Dongsonian society. It is also found in their military hierarchy: the wearing of metal armor was reserved for the great military chiefs. Lesser chiefs had to make do with leather cuirasses or tree bark coats of armor, similar to those of the Dayak in Borneo, Indonesia.

During recent archaeological excavations, Vietnamese archaeologists are confronted with the burial practices used by the Dongsonians. They employed various modes of burial: interments in pits (mộ huyện đất) with the deceased in a lying or crouching position (Thiệu Dương), burials in dugout coffin boats (mộ thuyền) (Việt Khê, Châu Can, Châu Sơn), burials in bronze jars or inverted drums (mộ vò). ( Đào Thịnh, Vạn Thắng) .

The burial mode in boat-shaped coffins has only been found in certain regions of Northern Vietnam (Hải Phòng, Hải Hưng, Thái Bình, Hà Nam Ninh, and Hà Sơn Bình). The area is very limited compared to the zone of influence of the Đồng Sơn culture. On the other hand, in famous Dong Son sites such as Làng Cả (Vĩnh Phú), Đồng Sơn, Thịệu Dương (Thanh Hoá), Làng Vạc (Nghệ Tĩnh), no burial mode involving boat-shaped coffins has been reported. Some Vietnamese archaeologists like Hà Văn Tấn believe that the coffins had the possibility of being preserved because they were located in a marshy area. This is not the case for other coffins, as they were situated in unfavorable places where water could erase everything over time.

According to Vietnamese archaeologist Hà Văn Tấn, the marsh area could have been, during the Dong Son period, a swampy region where people lived under conditions similar to those who habitually soaked their skin and skeleton in water throughout their lives and in death. (Sống ngâm da, chết ngâm xương). It is not surprising to find in these people their way of thinking and their method of burying the dead in boat-shaped coffins because for them, from birth to death, the means of transport was always the boat.

Other archaeologists question the disappearance of this custom among the Vietnamese. Why does this burial method continue to be practiced by the Mường, close cousins of today’s Vietnamese? Yet they share the same ancestors. The explanation that can be given is as follows: the diversity of burials clearly shows the « disparate » nature among the Dongsonians. Considered as Indonesians (or Austroasians (Nam Á in Vietnamese)), they are in fact populations of the same culture but remain physically heterogeneous. According to Russian researchers Levin and Cheboksarov, the Indonesians would be a mix of Australoids and Mongoloids. They originated from the fusion of the Luo Yue (Lac Việt), (Australo-Melanesian elements, ancient inhabitants of eastern Indochina who still remained on the continent) and Mongoloid elements probably coming via the Blue River from the borders of Tibet and Yunnan during the Spring and Autumn period (Xuân Thu). It does not appear that physical diversity is accompanied by cultural diversity. At each era, the same tools and customs seem common to all. If there is a difference in the burial method, this can be explained by the lack of resources and forced Sinicization among the Vietnamese. This is not the case for the Mường, who, taking refuge in the most remote corners of the mountains, can perpetuate this custom without any difficulty.

According to archaeologist Hà Văn Tấn, it is possible to find oneself in this hypothesis illustrated by the example of the burial method, which is carried out differently today among the Southern Vietnamese (descendants of a mixture of Vietnamese, Chinese, Chams, and Khmers) and those from the North, even though they come from the same people and the same culture.

It is through picturesque traits that we begin to better understand the Dongsonians during archaeological excavations. There is no longer any doubt about their origin. They belonged to the Hundred Yue or Bai Yue because in them we find everything related to the Bai Yue: tattooing, teeth lacquering, betel chewing, worship of totem animals, stilt houses, use of drums, etc., among the 25 characteristic elements found among the Yue and cited by the British sinologist Joseph Needham. They were designated in Chinese annals by different generic names: Man Di during the Spring and Autumn period, Hundred Yue (or Bai Yue) during the Warring States period (Tam Quôc), Kiao Tche (or Giao Chi in Vietnamese) during the Han (or Chinese) domination.

According to Vietnamese scholar Đào Duy Anh, the name Kiao Tche (Giao Chỉ) given to the Yue peoples in northern Vietnam originally designates the territories occupied by the Yue who worship the kiao long (giao long) (crocodile-dragon), kiao and tche meaning respectively dragon and territory.

This hypothesis was adopted and supported by Vietnamese archaeologists Hà Văn Tấn and Trần Quốc Vượng. This crocodile-dragon, a totemic animal of the Dongsonians, is found in funerary artifacts: axes, spears, armor plates, and thạp vases (for example, Đào Thịnh). It is from this multiple mixture of Dongsonians with other ethnic groups from Si Ngeou (Tây Âu), ancestors of the Tày, Nùng, Choang, and close relatives of the Thai in the mountainous regions of Kouang Si (Guangxi) and Northern Vietnam at the beginning of the Iron Age (3rd century BC, Âu Lạc period) that today’s Vietnamese originate.

The territory of the Hundred Yue is so vast that it forms an inverted triangle with the Yangtze River (Dương Tử Giang) as the base, Tonkin (Northern Vietnam) as the apex, the regions of Tcho-Kiang (Zhejiang), Fou Kien (Fujian), and Kouang-Tong (Guangdong) on its eastern side, and the regions of Sseu-tchouan (Sichuan), Yunnan (Vân Nam), Kouang Si (Guangxi) on its western side. (Paul Pozner).

Many chiefdoms were established there, and there were no borders hindering the spread and circulation of their traditions, particularly the making and use of bronze drums. This is why it is possible that bronze drums were made at the same time in distinct centers within the territories of the Yue (Vietnam, Yunnan, Guangxi) according to different casting techniques (lost-wax casting in Vietnam, mold sections in Yunnan) and according to the availability of local mining resources.

In the analyses of Ðồng Sơn bronzes, it is observed that the percentage of lead is higher than that of tin, which is an exceptional fact in the technology of Dong Son bronze. But it is surprising to find roughly the same lead and tin content in the analysis of the Kur drum bronze in Indonesia. It would have been impossible for the Indonesians of that time to chemically analyze this drum to know the content of each metal. They must have learned from the Dong Son people either directly or indirectly. This strongly supports the hypothesis of the diffusion of metallurgy from the Red River basin starting in Vietnam, unless Dong Son metallurgists were present on their territory at that time.

Moreover, the Dong Son people knew how to seek an appropriate alloy for each type of object they made. This is the case with the weapons found in the Dong Son burial sites, where the lead content is lower and the tin content quite significant, giving them a remarkable degree of hardness. Furthermore, the percentages of metals in the chemical composition of the bronzes from Jinning (Yunnan) are roughly the same as those of ancient Chinese bronzes. (Nguyễn Phước Long: 107). This is not the case with the Dong Son bronzes.

These were local and original products and belonged to the Red River civilization. Living on the edge of the East Sea or South China Sea (Biển Đông), the Dong Son people were close to major trade routes, which allowed for a wide dissemination of their culture and their bronze drums. It was about 2 km from the Vietnamese coast in the Vũng Áng region (Hà Tĩnh) that a Vietnamese fisherman accidentally caught two objects in his net in 2009 in the East Sea: a bronze axe and a spearhead dating from the Đồng Sơn period.

This proves that the Dongsonian people used maritime routes to establish a network of exchanges with all the states bordering the South China Sea (starting from the north, clockwise). In Zhejiang (Triết Giang), during an archaeological excavation at Thượng Mã Sơn (An Cát, Hồ Châu or Huzhou Shi), Chinese archaeologists found an object that was not native to this region and undoubtedly belonged to the Dongsonian civilization. It is a bronze drum similar to the one found in Lãng Ngâm in Bắc Ninh province in Northern Vietnam. (Trịnh Sinh 1997). Then in Canton, in the tomb of King Zhao Mei (Triệu Muội), identified as the second ruler of Nan Yue and known as Nam Việt Vương in Vietnamese, cylindrical situlas with geometric decoration (thạp) were discovered, frequently found in Dongsonian sites in Vietnam. Finally, along the Vietnamese coast (Champa, Chenla), in territories where the Sa Huỳnh culture was present at that time, bronze drums, daggers, and Dongsonian axes were also found in bronze jar burials (mộ vò).

Further inland, on the island (Hòn Rái) of Kiên Giang province, near Phú Quốc island, in the Gulf of Siam, a Đông Sơn bronze drum was discovered in 1984 during the exhumation of bodies, inside which were found axes, spearheads, as well as human bones. We must also not forget the bronze drums found in Thailand, characterized by the three elements copper, lead, and tin, with lead content reaching up to 20% (U. Gueler 1944), which testifies to one of the characteristics of Đông Sơn bronzes (Trinh Sinh: 1989: 43-50). The Đông Sơn civilization developed in a very open environment. In northern Vietnam, the flow of information and objects was facilitated by the Red River, which originates in Yunnan and was considered the river Silk Road between the Dian kingdom and that of the Đông Sơn people. Benefiting from the abundance of mineral deposits in their territory and the proximity to the coasts of the East Sea, they succeeded in developing a spectacular bronze art and imposing a very original and distinctive style through their bronze drums, situlas, and magnificent objects, which probably explains their leadership role in mastering lost-wax casting and facilitating exchanges not only within the Yue territories but also in territories as distant as those.

For the Dongsonians as for the Yue, the bronze drum was not only a common cult heritage that they were supposed to keep carefully but also an emblem of power and rallying beyond their village and ethnic community. The bronze drum, which guaranteed agrarian rites and social cohesion, was made by talented local metallurgists solely to perpetuate their ancestral tradition, never considering that their artistic work could become an object of dispute between the two peoples, Vietnamese and Chinese, one being considered the legitimate heir of the Hundred Yue and supposed to revive the civilization of its ancestors, that of the Bai Yue, and the other, conqueror of the territories of the Bai Yue and supposed to restore to the descendants of the Yue the place they deserve in today’s China. One cannot remain indifferent to the hypothesis defended by the sinologist Charles Higham in his work entitled « The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia« :

The search for origins and changes occurring in the second half of the 1st millennium BCE in the region leads to the overlooking of an important point. These changes taking place in what have become today the south of China and the Red River Delta basin were accomplished by groups exchanging their ideas and goods in response to strong pressure from the north, from powerful and expansionist states (Chu (Sỡ), the Qin (Tần), and the Han (Hán)) who ultimately managed to crush them.

From a historical and cultural perspective, all those descended from the Yue have the right to claim this heritage. But from a logical standpoint, only the Luo Yue (or the Dongsonians) among the Baiyue succeeded in forming a nation and having an autonomous and independent country (Vietnam). This is not the case for the other Yue, who were all sinicized over the centuries during the imperial expansion initiated by the Qin and the Han. No one has the right to contest the Yue character in present-day Vietnamese. This is also the observation made by the French ethnologist Georges Condominas:

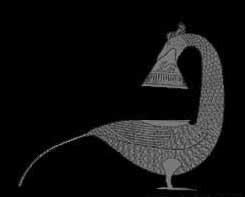

Mentioning the Yue is to go back to the origins of Vietnamese identity. (G. Condominas). It is obvious that the paternity of the bronze drums belongs to the Vietnamese, especially since these sacred instruments could carry a message left to them by their ancestors (the Dongsonian people). The inscription engraved on the bronze column of General Ma Yuan is well known: Let this column fall and Giao Chỉ will disappear (Ðồng trụ triệt, Giao Chỉ diệt). Where is this bronze column when we know that Giao Chi (Vietnam) continues to exist today? By closely observing a bronze drum, one notices that it resembles a cut tree trunk. Its tympanum bearing several concentric circles is analogous to the cross-section of the trunk with rings added over the centuries.

Does the bronze drum evoke Ma Yuan’s bronze column? Some scientists believe that the bronze drum is the « tree of life. » This is the case for the Russian scientist N.J. Nikulin from the Moscow Institute of Culture. Relying on the discoveries and suggestions of Vietnamese researchers (such as Lê Văn Lan) about the idea of a « totality » represented by the bronze drum through its depictions, he arrives at the following conclusion: The bronze drum is a representation of the universe: the tympanum (or the plate), symbolizing the celestial and terrestrial world (thiên giới, trần giới), the trunk representing the marine world (thủy quốc), and the base representing the underground world (âm phủ). According to him, there is an intimate relationship between the bronze drum and the mythical narrative of the Mường, close relatives of the present-day Vietnamese.

In the Mường conception of the creation of the universe, the tree of life symbolizes the notion of universal order, as opposed to the chaotic state found at the moment of the world’s creation. The worship of the tree is a very ancient custom of the Vietnamese. The areca palm found in the betel quid (chuyện trầu cau) testifies to this worship. According to historian and archaeologist Bernet Kempers, the bronze drum illustrates a fundamentally monistic (Oneness) vision of the cosmos.

It is this bronze drum that the Han wanted to destroy to seal the fate of the Dongsonians because it was the tree of life symbolizing both their strength and their conception of life. Fortunately, over the centuries, the bronze drum did not disappear, but thanks to the picks and shovels of French and Vietnamese archaeologists, it reappeared splendid and radiant, allowing the descendants of the Dongsonians to rediscover their true history, their origin without being seen as cooked barbarians.

Being a sacred instrument, the bronze drum is more than ever involved in the restoration and testimony of the identity of the Vietnamese people, which was nearly erased many times by the Middle Kingdom throughout its history.

[Return CIVILISATIONS]