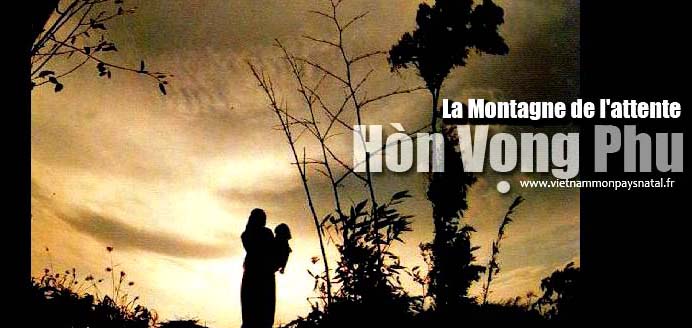

This mountain, known as » Núi Vọng Phu » (The Mountain of the Woman who is waiting for her husband) is located not far from Lạng Sơn, quite close to the Sino-Vietnamese border. At the top of the mountain is a rock bearing the shape of a standing woman holding her child in her arms. This resemblance is striking when the sun sets on the horizon. The tale of this mountain is so touching it becomes thus one of the legends preferred by Vietnamese and gives so much inspiration to Vietnamese poets, in particular composer Lê Thương through his three songs Hòn Vọng Phu I, II and III presented here in format mp3.

Long time ago, in a village on the highland region, lived two orphans, one was a young man about twenty years old, the other was his seven years old sister. Because they were alone in this world, they were all one for the other. On a beautiful day, a traveling astrologer told the young man when he consulted him on their future:

<< If I’m not mistaken, you will fatally marry your sister with all your days and hours of your births. Nothing could turn the course of your destiny >>.

Tormented by this terrible prediction, he decided to kill his sister on a beautiful morning when he suggested to take her to the forest to cut wood. Taking advantage of his sister’s inattention, he felled her with a stroke of ax and fled. He decided to change his name and resettled in Lang Son. Many years went by. On a beautiful day he married a merchant’s daughter who gave him a son and made him happy.

On a beautiful morning, he found his wife sitting in the back yard drying her long black hair under the sunshine. At the time when she glided the comb on her hair that she lifted with her other hand, he discovered a long scar above the back of her neck. Surprised, he asked her for its cause. Hesitating, she began to tell the story crying:

<< I am only the adoptive daughter of the merchant. Orphaned, I lived with my brother who, fifteen years ago for unknown reasons, injured me with a blow of an ax and abandoned me in the forest. I was rescued by the robbers who sold me to this merchant who had just lost his daughter and who was sorry for my situation. I don’t know what happened to my brother and it is hard for me to explain his insensitive act. However we love each other so much.>>

The husband overcame his emotion and asked his wife for information concerning her father’s and brother’s names and her native village. Taken by remorse while keeping for himself the frightening secret, he was ashamed and horrified himself. He tries to stay away from his wife and his son by taking advantage of the military draft to enroll in the army and hoping to find the delivery on the battleground.

From the day of his departure, in ignorance of the truth, his wife waited for him with patience and resignation. Every evening, she took her son in her arms and climbed up the mountain looking out for the return of her husband. She made the same gesture for entire years.

On a beautiful day, reaching the top of the mountain, exhausted and stayed standing, her eyes fixed to the horizon, she was changed into rock and immobile in her eternal wait.