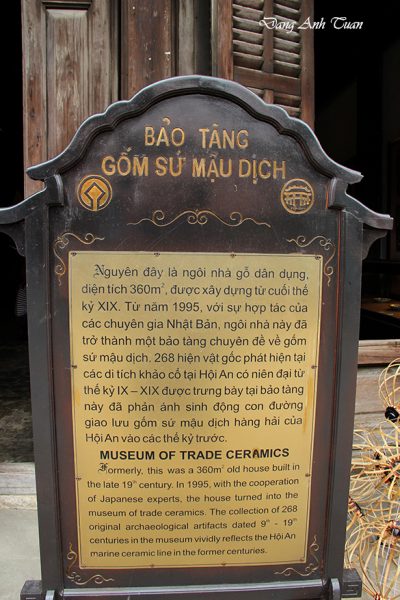

Musée du commerce de la céramique

Lịch sử Việt Nam.

Le mythe de Táo Quân

English version

Version vietnamienne

Galerie des photos

Le mythe des génies du foyer repose sur la tragique histoire d’un bûcheron et de sa femme. Il prend sa source dans le taoïsme. Ce couple modeste vivait heureux jusqu’au jour où il découvrit qu’il ne pouvait pas avoir d’enfants. L’infortuné mari se mit à boire et à maltraiter sa femme. Celle-ci ne pouvant en supporter davantage le quitta et épousa un chasseur d’un village voisin. Mais un jour, fou de solitude et plein de remords, le bûcheron décida de rendre visite à sa femme pour lui présenter ses excuses.

Sur ces entrefaites, le chasseur rentra chez lui. Afin d’éviter tout malentendu, la jeune femme cacha son premier mari dans une étable au toit de chaume, située près de la cuisine où le chasseur était en train de fumer son gibier. Par malheur, une braise s’échappa du foyer et mit le feu à l’étable.

Affolée, la jeune femme s’élança vers l’étable en flammes pour sauver son ex-époux. Le chasseur la suivit pour lui porter secours et tous trois périrent dans le brasier. L’empereur de Jade (Ngọc hoàng), du haut de son trône céleste, profondément touché par ce triste sort, divinisa les trois malheureux et les chargea de veiller au bien-être des Vietnamiens à l’emplacement avantageux de la cuisine. C’est ainsi qu’ils devinrent dès lors les génies du Foyer.

Pendant la semaine où les génies sont au ciel, les Vietnamiens craignent que leur maison soit sans protection. Afin de prévenir toute incursion des mauvais esprits dans leur maison, ils érigent devant chez eux une haute perche de bambou (cây nêu) sur laquelle sont suspendues des plaques en argile (ou khánh en vietnamien) vibrant avec sonorité au gré du vent pour éloigner les esprits. Au sommet de cette perche, flotte un morceau de tissu jaune marqué par l’emblème bouddhique.

Cette coutume trouve ses origines dans une légende bouddhique intitulée « Le Tết du bûcheron » selon laquelle les Vietnamiens doivent affronter des esprits maléfiques.

C’est toujours le vingt-troisième jour du dernier mois lunaire que chacun des Vietnamiens organise une cérémonie de départ du génie de foyer pour le ciel. On trouve non seulement sur son autel des fruits, des mets délicieux, des fleurs mais aussi un équipement de voyage approprié (3 paires de bottes, 3 chapeaux, vêtements, des papiers votifs) et des trois carpes mises dans une petite cuvette. À la fin de la cérémonie, on brûle les papiers votifs et on libère les carpes dans un étang ou dans une rivière afin que le génie puisse s’en servir pour s’envoler au ciel. Celui-ci doit rapporter tout ce qu’il a vu sur terre à l’empereur de jade, en particulier dans le foyer de chaque Vietnamien. Son séjour dure ainsi six jours au ciel. Il doit retourner au foyer dans la nuit du réveillon jusqu’au moment où débute la nouvelle année.

(*) cây nêu: C’est un arbre cosmique reliant la terre au ciel en raison des croyances des peuples anciens adorant le soleil, y compris les Proto-Vietnamiens mais il est employé également pour délimiter leur territoire.

Truyền thuyết về các Táo quân được dựa trên câu chuyện bi thảm của một người thợ rừng và vợ của ông ta. Nó có nguồn gốc từ Lão giáo. Cặp vợ chồng khiêm tốn này được sống hạnh phúc cho đến khi họ phát hiện ra rằng họ không thể có con. Người chồng bất hạnh nầy mới bắt đầu rượu chè và ngược đãi bà vợ. Bà nầy không thể chịu đựng được nữa và rời bỏ ông ta và kết hôn với một người thợ săn ở làng bên cạnh. Nhưng một ngày nọ, cô đơn và hối hận, người thợ rừng quyết định đến thăm vợ để xin tạ lỗi.

Giữa lúc đó, người thợ săn trở về nhà. Để tránh mọi sự hiểu lầm, người phụ nữ trẻ buộc lòng giấu người chồng cũ của mình ở trong một chuồng gia súc có mái nhà bằng tranh, nằm gần nhà bếp nơi mà người thợ săn đang hun khói thịt rừng. Thật không may, một đóm lửa than hồng thoát ra khỏi lò và đốt cháy chuồng.

Cùng quẫn, người phụ nữ trẻ lao mình về phía chuồng đang bốc cháy để cứu chồng cũ. Người thợ săn chạy theo cô để giúp cô và cả ba đã chết trong ngọn lửa. Ngọc Hoàng, từ trên cao nhìn xuống, cảm động vô cùng trước số phận đau buồn này, phong thần cho ba người và buộc họ phải trông chừng từ đây hạnh phúc của người dân Việt ở vị trí thuận lợi của nhà bếp. Bởi vậy họ trở thành các thần bếp núc từ đây của các gia đình người Việt.

Trong tuần lễ các táo quân ở trên trời, người Việt lo sợ ngôi nhà của họ sẽ không được bảo vệ. Để ngăn chặn sự xâm nhập của tà ma vào nhà, họ dựng trước cửa nhà một cây nêu có treo những khánh đất phát tiếng động khi có gió rung. Trên đỉnh cột này có treo một mảnh vải màu vàng có biểu tượng của Phật giáo.

Phong tục này bắt nguồn từ một truyền thuyết Phật giáo mang tên « Tết của người thợ rừng », theo đó người dân việt phải đối mặt với những linh hồn ma quỷ.

Cứ đến ngày hai mươi ba tháng Giêng âm lịch, mỗi người dân Việt lại tổ chức lễ tiễn Táo quân về trời. Không chỉ có trái cây, thức ăn ngon, các bông hoa trên bàn thờ của Táo quân mà còn có đồ dùng cho cuộc hành trình thích hợp (3 đôi giầy, 3 cái mũ, 3 bộ đồ quần áo, vàng mã) và ba con cá chép được đặt trong một chiếc thau nhỏ. Sau khi kết thúc lễ cúng thì đốt vàng mã và thả cá chép xuống ao hay sông để Táo quân mượn cá chép bay về trời. Táo quân phải báo cáo lại với Ngọc Hoàng tất cả những gì Táo quân được nhìn thấy ở trần gian, nhất là ở trong nhà của mỗi gia đình của người dân Việt. Thời gian lưu trú của Táo quân được kéo dài là sáu ngày ở trên trời. Táo quân phải trở về nhà vào đêm giao thừa đúng lúc khi năm mới vừa bắt đầu.

(*) cây nêu: cây vũ trụ nối liền đất với trời, do tín ngưỡng thờ thần mặt trời của các dân tộc cổ mà trong đó có người Việt cổ mà còn hàm chứa ý thức về lãnh thổ cư trú của họ.

The betel quid

French version

Vietnamese version

Long time ago, under the reign of king Hùng Vương the 4th, there were two twin brothers, Cao Tân and Cao Lang. They looked so much alike that it was difficult to distinguish one from the other. They both attended the school of an old teacher in the village who had a sole daughter named Liên whose beauty attracted all the homage of all the young men in the area.

The old teacher liked both of them. He would grant his daughter’s hand to one of them, preferably the elder because according to Vietnamese customs, the elder brother would get married first. In order to be able to distinguish them, he relied on a little trick by inviting them for dinner. The one who first picked up the chopsticks would be the elder. So Cao Tân got the hand of his daughter without any doubts that his younger brother has devoted an ardent love to her. They went on to live together in a complete harmony and experienced a faultless happiness.

Cao Tân continued no less to love his younger brother like ever before and would do anything to make him happy.

However, in spite of that, the younger brother could not rid of the pain in his heart. He decided to leave them and went out for an adventure. After so many days of walking, he ended up falling exhausted on the road and was transformed into a block of lime stone with an immaculate white.

The elder brother, taken by growing worries for his younger brother left in search for him. He followed the same road taken by his younger brother. In a beautiful morning, after so many days of walking, he arrived at the lime stone block, sat on it and succumbed without movement. He was metamorphosed in to a betel nut tree growing tall with its green palms and oblong little fruits. The tree began to extend its branches and its shadow over the lime stone mass as if to protect it from the changes of weather.

Staying at home without any news from her husband, the young wife in turn left the house and went for a search of her spouse. She roamed fields, crossed villages and finally one day, she came real close to the tree. Tired by the long walk, she leaned back at the foot of the tree, took her turn to die and change into a plant whose stems curled around the trunk of the tree with large intensely green leaves in the form of a heart.

One day, while passing through the area, King Hùng heard this story. He tried chewing betel and areca with a little of the lime from the limestone block. He found that the resulting saliva was as ruddy as blood, with a fresh, tangy and fragrant taste. From then on, he ordered betel and areca to be included in the wedding ceremony as a ritual offering. This is one of the Vietnamese customs that must be observed at the wedding feast. Areca nuts and bright green betel leaves in the shape of a heart are always part of the wedding gifts, symbolizing the pledge of marital love and fidelity.

Similar to a cigarette, betel quid was a conversation starter in old Vietnamese society. That’s why it’s customary to say in Vietnamese “Miếng trầu là đầu câu chuyện”. The betel quid is also used to measure time, because in the absence of clocks in those days, a mouthful of betel corresponds to roughly three or four minutes, giving you an idea of how long a conversation lasted.

The betel quid

This is one of Vietnamese customs to be observed at a marriage ceremony. There is always betel, with betel nut and intensely green leaves in the form of a heart that is part of wedding gifts that symbolize an eternal union.

Photo Đinh Xuân Dũng ( Nha Trang )

Intangible Heritage of Humanity by

Unesco in 2005

Last part

In the ritual ceremonies, the players of gongs move slowly in single file or in half-circle in front of a public admirer. They left from right to left in the counterclockwise direction to go back in time and return to their origins. Their footsteps are slow and rhymed to the beats of gongs, each of which has a well-defined role in the set. Each gong corresponds exactly to a guitar string, each having a note, a particular tone. Whatever the melody played, there is the active participation of all the gongs in the procession. However, an order very precise in the sequence and composition of beats is imposed in order to respond to the melodies and own themes chosen by each ethnic group.

Sometimes, to better listen to the melody, the auditor has the interest to be into a location equidistant from all the players arranged in a half circle otherwise he cannot listen properly because of the weakness and amplification of the resonance of some gongs corresponding respectively to the distance or the excessive closeness of its geographical position relative to one another.

For most of ethnic groups, the set of gongs is reserved only for men. This is the case of the ethnic group Jarai, Edê, Bahnar, Sedang, Co Hu. By contrast, for the ethnic group Eđê Bih, women are allowed to use the gongs. In a general way, the gongs are of variable size. The disk of the major gongs may vary from 60 to 90 cm in diameter with a cylindrical edge from 8 to 10 cm. This does not allow the players to wear them because they are too heavy.

These gongs are suspended often to the beams in house by the ropes. However, there are the gongs more small whose disk varies from 30 to 40 cm with an edge from 6 to 7cm. The latter are frequently encountered in the festive rituals.

For the identification of highland gongs, the Vietnamese musicologist Trần Văn Khê has the opportunity to enumerate a number of characteristics in one of his articles:

The composition of the played melody is based primarily on the sequence of beats settled according to original processes of repetition and answer.

One doesn’t finds elsewhere as many gongs as one had them on the Highlands of Vietnam. That is why, during his visit in Vietnam, the ethnomusicologist Filipino José Maceda, accompagned by Vietnamese musician Tô Vũ, had the opportunity to emphasize that the highland gongs are very original when he was in contact with the gongs. For him, because of the large number of gongs found, it is possible the Highlands may be the gong cradle in Southeast Asia.

Over the years, the risk of seeing the « original » and « sacred » character is real because of the illicit trafficking of gongs, the lack of gong tuner, the disinterestedness of young people and the destruction of natural environment where the gongs have been « educated ».

Highlands Gongs

For a few years, being regarded as cultural goods, the gongs become the object of all desire for Vietnamese antique dealers and foreign collectors, which brings the local authorities to exercise strict control with the aim of stopping the haemorrhage of gongs (chảy máu cồng chiêng)

The governmental effort is also visible at the local level by the establishment of incentive programs for learning with young people. But according to some Vietnamese ethnomusicologists, this allows to make durable the gongs without giving to the latter the means to possess a soul, a sacred character, a ethnic sound color because they need not only the skillful hand and fine hearing of gong tuner but also the environment. This is the latter factor that one forgets to protect effectively during the last years. Because of the intensive deforestation and galloping industrialisation for the coming years, the ethnic minorities don’t have the opportunity to practice slash and burn agriculture. They will not have any occasion to honor the ritual festivals, their genius and their traditions. They no longer know to express sorrows and joys through the gongs. They don’t know their oral epics (sử thi). Their paddy fields are replaced by coffee and rubber plantations. Their children are no longer forest clearers but they are engaged to industrial and tourist activities, which allows them to have comfortable livelyhoods. Few now recall how to tune these gongs.

The character « sacred » of gongs no longer exists. The latter become instruments of entertainment like other music instruments. They can be used anywhere without significant events and very specific and sacred hours (giờ thiêng). They are played according to the tourism demand. They are no longer what they were until now.

It is for this irreparable loss that UNESCO has not hesitated to underline the urgency in the recognition of space of gong culture in the Central Highlands (Tây Nguyên) as the masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity on 25 November 2005. The gongs are only one essential element in the achievement of this masterpiece but it must be understood that other elements are as important as these gongs: the environment, the traditions and customs, the ethnic groups etc. ..

The gongs without their environment and their ethnic sound color no longer possess the sacred soul (hồn thiêng) of Central Highlands.They lose the original character for ever. There is always a price to pay in the preservation of the gong culture in Central Highlands but it is to the scope of our collective efforts and our political will. One cannot refute that the culture of the gongs in Highlands is part now of our cultural heritage.

[Back to page « Vietnam, land of 54 ethnies »]

The culture of the gongs is localized in the 5 provinces of central Vietnam (Đắc Lắc, Pleiku, Kontum, Lâm Đồng and Đắk Nong). Some twenty ethnic groups (Bahnar, Sedang (Xơ Đăng), Mnongs, Cơ Ho, Rơ Mam, Êđê, Jarai (Giarai people), Radhes etc ..) are identified in the use of these gongs. According to illustrated Vietnamese musicologist Trần Văn Khê, in the other countries of Southeast Asia, the gong player always remains seated and can play several instruments associated at the same time. This is not the case of the gong players of Highlands in Vietnam. Each player may play a single gong. There are as many gongs than players in a set.

Thanks to a thin string or to a band of cloth that can be more or less tightened by torsion, each player suspends the gong to the left shoulder. He struck the central dome of the gong outer face either with a wooden or leather mallet or with his right fist barren or wrapped up in fabric.

The sound quality of the gong depends not only on the alloy with which the gong has been manufactured but also the tuner quality. Other parameters are involved: the wooden or leather mallet, the position and action of the hand striking the gong, the tension of the strap etc. . In addition, the player can modulate skillfully the effects of the gong sound by varying the pressure and the relaxation on the bent edge of the outer face with his left hand. The muting effect may be caused by this action. Each ethnic group prefer a type of wood in the manufacture of the mallet. By choosing the hard wood, the Êđê often obtain interference noise in the power of the gong resonance. By contrast, in selecting the soft wood, the Bahnar manage to obtain the « clarity » of its fundamental tone despite the weakness of intensity detected in the resonance.

At the time of the purchase, the gong is delivered to the « raw » state, without musical tone, character and soul. Its outer face is almost flat. It is similar to an object producing an audible signal. (Cái kẻng) Thanks to the strokes of wooden mallet and to fine hearing of the tuner, the gong receives small bumps and concentric circles on its border and on its inner and outer faces. The blow of the mallet given on its outer face increase its tone.

By contrast, the decrease of the resonance is visible inversely with its inner face. The gong tuner manages to give it a sound color, a particular musical note, which makes it now a musical instrument in its own right. According to the highland people, analogous to the man, the gong has a face, a character and a soul. It is unlike any other gong.It is said that the gong is educated because from an object that is purchased with the « raw » state from the Kinh (or Vietnamese) (Quảng Nam), it receives an education, a note, an ethnicity, a sacred character. For the gong purchased in Laos, it already has a soul but it is a Laotian soul.

To transform it into a gong of the high plateaus, it must be educated by the blows of wooden mallet so that it knows as well the language Bahnar, Stieng, Edê, Mnong etc. It now has the sacred soul (hồn thiêng) of the high plateaus.

The latter does not disappear as long as there is still the environment where the gong is « educated » (the forest, the ethnic groups, the villages, the sources of water, the animals etc.) The sacred character of the gong can only be found in this natural environment which allows it to find its ethnic identity through the melodies varying from one village to another or from one ethnic group to another and the agrarian rites. The gong can produce a false note over the years of use. One says that it is « sick ».

It must be treated by bringing in a doctor (or a good musician tuner) that it is difficult to find sometimes on-site. It is necessary to travel several kilometers in other regions to succceed in finding him. Once readjusted the sound, it is said that the gong is healed.

Second part.

This general attempted to break down all the stirrings of Vietnamese resistance by melting all bronze drums, symbol of their power in combat. Probably, in this destruction, there was also the Dongsonian gongs because they were in bronze. According to the director of the South Asia prehistory center (Hànội), Nguyễn Việt, the Dongsonian situla cover whose center is slightly swollen and adorned with a star, strangely resembles the gong embossed of the high plateaus. It also owns the handles with which one can use the ropes for wall hanging as a gong. Perhaps it is the predecessor of the highland gongs.

We do not exclude the hypothesis with which the Dongsonian attempted to hide and sell them at any price in the mountainous regions through the cultural and economic exchange with the highland people.

From the linguistic research in particular that of French researcher Michel Ferguson, a specialist of Austroasiatic languages, this suggests that the Viet-Mường were present at the east of the Anamitic cordillera and on banks of Eastern China Sea (Biển Đông) before the beginning of our era. For this researcher, the group Viet-Mường lived together not only with the Tày but also with the highland people (the Khamou, the Bahnar etc … ). because there is the importance of the Tày vocabulary in the Vietnamese language and the similarities of the Giao Chỉ feudal structure with those of current Thai (descendants of proto-Tày).

In addition, there is a borrowing stratum from one or several languages viet-mường in the Khamou vocabulary. According to the suggestion of this researcher, the Tang Ming kingdom could be the former habitat of Việt-Mường group. This confirms the hypothesis the Dongsoniqan could be the provider of gongs to the highland people through the barter because the latter do not manufacture itself these gongs, despite their sanctity.

Probably, this is due to the fact that, being slash-and-burn agriculturalists, they had not a metallurgical industry enabling them to mold these gongs. Up to today, they obtain them from the Kinh (or Vietnamese), Cambodians, Laotians, Thais etc. before giving them to their musician with his keen hearing. This one manages to give to these gongs a remarkable set of harmonics in accordance with the themes devoted to villagers and tribes by hammering them with the hardwood mallets.

The adjustment of the gong sound is more important than the purchase because it must make the gong in harmony with the gongs of the orchestra and it is necessary to give it a soul, a particular tone. According to the Vietnamese musicologist Bùi Trọng Hiền, the process of collecting and tuning the gongs of different origins and making harmonious and consistent to their aesthetics in a set is a grandiose art. The gong must be sacred before its use by a ritual ceremony, which allow its body to possess now a soul.

Some ethnic groups bless the gongs with the blood in the same manner as jars, drums etc. This is the case of the Mnong Gar identified for example by the French ethnologist Georges Condominas. The sanctity of gongs cannot leave indifferent the Vietnamese. To give to these gongs a significant scope, the Vietnamese have the habit of saying:

Lệnh ông không bằng cồng bà (The drum of Mister does not resonate less loud to the human ear than the gong of Madam). This also explains that the authority of Mr. is less important than that of Madam.

First part

Since the dawn of time, the gong culture is the preferred approach used by the populations of the Central Highlands (Vietnam) living from agriculture in communication with the spirit world. According to their shamanistic and animist beliefs, the gong is a sacred instrument because it secretly houses a genius supposed to protect not only the owner but also his family, his clan and his village. Its âge not only improves its sound but also the power and magical potency of the occupier genius. In addition, the gong will acquire a special patina over the years. This percussion instrument cannot be considered as an standard musical instrument. It is present at all the important occasions of the village. It is inseparable from the social life of highland tribes. The newborn baby is invited to listen the sound of the gong played by the elder village from the first month of his birth, which allows him to recognize the voice of his tribe and his clan. He become now an element of his ethnic community. Then he grows over years to the rhythm of gong sound which carries him away with the fermented rice alcohol (rượu cần) in the evening meetings around a jar and fire and in the village festivals (offerings, marriages, funeral, celebrations of the new years’s day or the victory, inauguration of the new housing, family reunion, agricultural ritual (paddy germination, ear initiation, feast of the agricultural close etc.). Finally, at his death, he is accompagnied by the rolling of the gongs to the burial with solemnity.

According to the Edê, a life without gong is a life without rice and salt. Each family must have at least a gong because this instrument proves not only its fortune but also with its authority and prestige in its ethnic community and its region. In function of each village, the set of instruments can be simply represented by two gongs but you can find sometimes up to 9, 12, 15 or 20 gongs. Each of these is called by a name that indicates its position in a hierarchy similar to that found in a matriarchal family. According to French ethnomusicologist Patrick Kersale, the gongs reflect the image of the family structure with matrilineal inflection. For the Chu Ru, there are three gongs in a set. (Gong-mother, gong-aunt and gong-daughter). By contrast, for the Ê Đê Bih , the set of gongs consists of three pairs of gongs. The first pair is called under the name of gongs grand-mothers. And then the second pair is reserved for the gong-mothers and the last pair is for the gong-daughters.

In addition, there is a drum played by the oldest person to give the tempo. For peoples living in the south of the Highlands, there are also 6 gongs in a set but the gong-mother (chiền mẹ) remains the most important and is maintained slighty in the lower position compared with the other gongs. It is always accompanied by the gong-father followed then by the gong-children and gong-grandchildren. Due to their large size, the two gongs mother and father produce low sounds and nearly identical, which allows them to serve as a constituent basis to the orchestra.

In speculating about the provenance of gongs,we note they are found not only in India but also in China and in the region of Southeast Asia. Despite their mention in the Chinese inscriptions around the year 500 after Jesus Christ (period of Đồng Sơn civilization), there is a tendency to attribute to the Southeast Asia region their origin because the gong culture embraces only the regions where live Austro-asiatic and Austronesian peoples. (Vietnam, Kampuchea, Thailand, Myanmar, Java, Bali, Mindanao (Philippines) etc …). According to some Vietnamese scholars, the gongs are linked closely to the the aquatic rice cultivation. For the Vietnamese researcher Trần Ngọc Thêm, the gongs are used to imitate the noise of thunder. They have a sacred role in the annual ceremonies of rain making rituals, with the aim of having a good harvest. In addition, we find in these gongs an intimate binding with the Đồng Sơn culture because the gongs were present visibly on some bronze drums (Ngọc Lữ for example). The gongs had to be considered a sacred instrument in ritual celebrations so that they were honored by the Dongsonian on their drums. Among the Mường who are « close cousins » to the Vietnamese, one continues to associate the bonze drums (character Yang) with the gongs (character yin) which the Mường still regard as a stylized representation of the woman chest in religious festivals. These gongs are in some way the symbol of fertility. According to the Vietnamese musician Tô Vũ, the Mường forced back in the inaccessible mountainous regions, could continue to keep carefully these gongs against the Chinese conquerors. This is not the case of the Dongsonian (the ancestors of the Vietnamese) during the Chinese conquest led by the general Ma Yuan (or Mã Viện) of West Han dynasty after the sisters Trưng Trắc and Trưng Nhị revolt. More reading (Tiếp theo)

Bibliographic references