Pont Bir Hakeim

Art

Art des pays d’Asie du Sud ou de la France

Arc de triomphe de Carrousel (Paris)

Place des Vosges (Paris)

ukiyo-e japonais (Các bức tranh của thế giới nổi trôi)

Les estampes du monde flottant

Les estampes du monde flottant

Nghệ thuật vẽ các bức hình của thế giới trôi nổi được sinh ra ở thời Edo, một thời kỳ mà con người luôn tìm kiếm hoan lạc mà cũng là thời kỳ của Mạc chúa Tokugawa đã thành công thống nhất xứ Phù Tang và đóng đô ở Edo nay là thủ đô Tokyo. Các bức hình vẽ nầy đã ảnh hưởng rất nhiều đến những hoạ sĩ nổi tiếng như Matisse, Monet và Van Gogh. Các bức hình vẽ nầy phản ảnh một thế giới sôi động và phức tạp với những thú vui phù du và tinh tế mà giới giai cấp tư sản ở thành thị thường ưa thích trong cuộc sống hằng ngày như ca kịch, thơ hay bên cạnh các kỹ nữ.

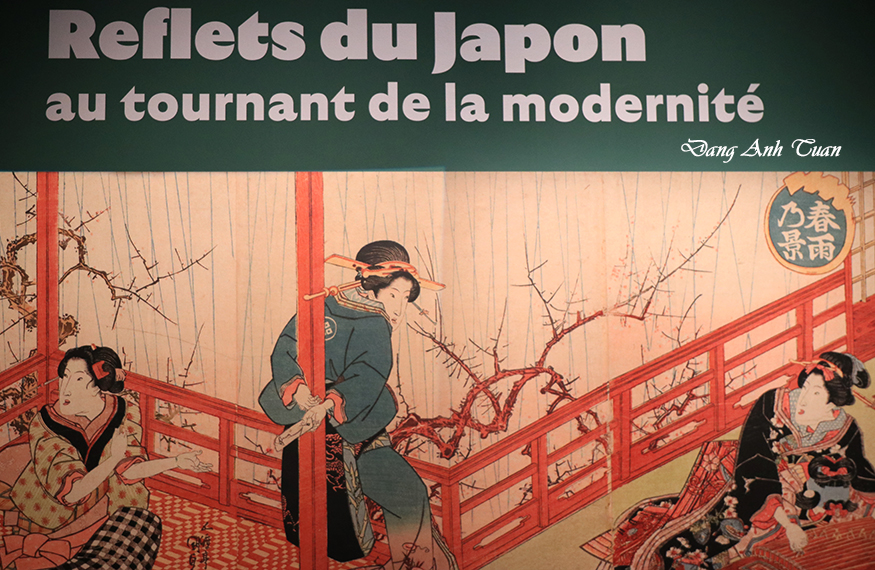

Kỹ thuật in khắc hình trên gỗ cho phép sản xuất hàng loạt và phân phối những hình ảnh rẻ tiền và định dạng khác nhau, ban đầu nhằm mục đích quảng cáo. Kỹ thuật nầy bắt đầu được thực hiện vào đầu thế kỷ XIX bởi các nghệ sĩ đến từ trường Utagawa (Kuniyoshi, Kunishada) mà một số tác phẩm được chọn và trưng bày gần đây bởi Bảo tàng Cernuschi ở Paris với tựa đề « Những phản ảnh của Nhật Bản bước vào thời kỳ tân tiến ».

L’art de peindre des images du monde flottant (ou ukiyo-e) est né à l’époque d’Edo, une période où les gens cherchaient toujours le bonheur, mais c’est aussi l’époque où le shogun Tokugawa a réussi à unifier le Japon et à fonder la ville d’Edo qui devient aujourd’hui la capitale de Tokyo. Ces estampes ont beaucoup influencé des peintres célèbres occidentaux comme Matisse, Monet et Van Gogh. Ces peintures reflètent un monde effervescent et complexe avec des plaisirs subtils et éphémères que la bourgeoisie urbaine appréciait souvent dans la vie quotidienne comme le théâtre, la poésie ou encore la compagnie des courtisanes.

La technique de l’estampe sur bois facilitant la production et la diffusion de masse de ces images peu onéreuses et sous des formats différents a pour but de servir la publicité. Elle commence à se réaliser au début du XIXème siècle avec des illustres artistes issus de l’école Utagawa (Kuniyoshi, Kunishada) dont certaines œuvres ont été choisies et exposées pour le thème intitulé « Reflets du Japon au tournant de la modernité » du musée Cernuschi (Paris).

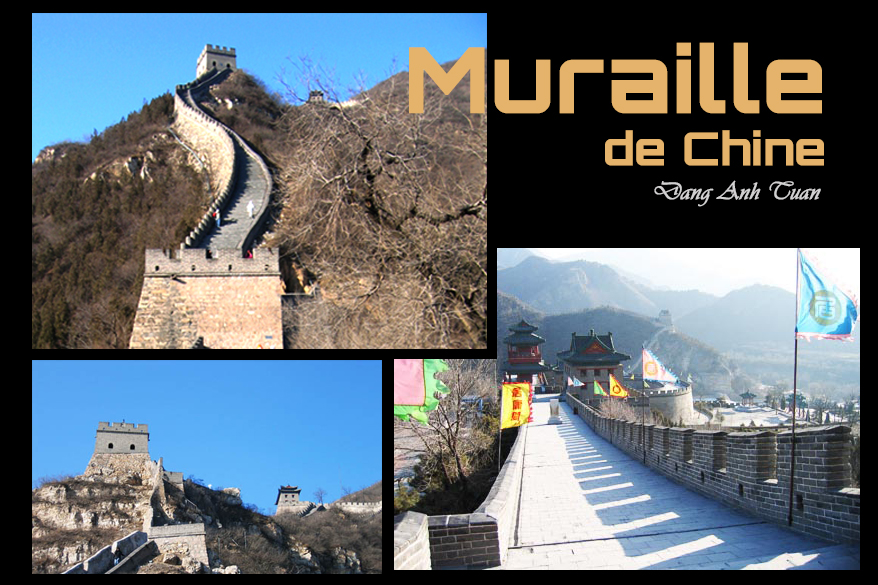

La Muraille de Chine (Vạn Lý Trường Thành)

Vạn Lý Trường Thành

Vạn lý trường thành gồm rất nhiều đồn lũy quân sự và phòng thủ nằm rải rắc ở các địa điểm khác nhau ở biên giới phía bắc Trung Quốc. Được biết đến với tên tiếng Hoa là “Vạn Lý Trường Thành”, nó bắt đầu ở phía đông tại Sơn Hải Quan, thuộc tỉnh Hà Bắc và kết thúc tại Gia Dục Quan ở phía đông tỉnh Cam Túc. Với chiều dài hơn 5000 cây số, nó là biểu tượng của Trung Quốc ngày nay. Những phần gần Bắc Kinh đã được khôi phục nhưng ở phía Bắc vẫn còn những đoạn tường dễ bị sụp đổ. Công trình phòng thủ rộng lớn này được xây dựng từ thời nhà Chu vào thế kỷ thứ 9 trước Công nguyên để bảo vệ đất nước tránh sự xâm lăng của dân man rợ ở phương Bắc. Đây là lý do tại sao không chỉ có tường và đường đi cho kỵ sĩ mà còn có cả các tháp canh.

Vào năm 1987, Vạn Lý Trường Thành đã được UNESCO công nhận là di sản thế giới. Nó còn được công nhận là công trình kiến trúc nhân tạo duy nhất trên trái đất có thể nhìn thấy từ mặt trăng. Dưới thời Chiến Quốc, các bức tường khác được các lãnh chúa của các vương quốc này dựng lên nhầm bảo vệ đất nước. Các nhà sử học gọi chúng là “ các bức tường thời tiền Tần”. Sau khi đất nước được thống nhất, người ta kể rằng trong giấc mơ, Tần Thủy Hoàng đã nhìn thấy sự tan rã đế chế của mình bởi những kẻ man rợ từ phương Bắc. Bị ám ảnh bởi giấc mơ này, ngài mới giao cho tướng Mộng Điềm liên kết lại các bức tường của sáu nước bị chinh phục này để chống lại bọn man rợ này. Nhà Minh đã thực hiện công việc tu bổ sửa chửa hoàn tất lại kéo dài khoảng 200 năm.

Đây chính là bức tường nhà Minh mà chúng ta thấy ngày nay. Đây cũng là ý kiến của Arthur Waldron, tác giả cuốn sách có tựa đề “Vạn Lý Trường Thành của Trung Quốc. Từ lịch sử đến thần thoại”. Theo ông, bức tường Trung Quốc không thể tiến xa hơn vào cuối thế kỷ 15 và nửa đầu thế kỷ 15. Nó đi từ đèo Shanhaiguan về phía đông và Jiayuguan đèo Jiayu (Jiayuguan) ở phía tây trên chiều dài 5660 cây số. Có thể nói, việc xây dựng Vạn Lý Trường Thành chưa bao giờ bị gián đoạn hoàn toàn trong suốt hai ngàn năm, từ thời Chiến Quốc đến thời nhà Thanh. Theo ghi chép lịch sử, việc xây dựng nó có huy động hàng trăm ngàn nông dân. Hơn nữa, trong suốt thời gian làm việc ngày đêm , có hơn 1,5 triệu người tham gia, không quên ghi nhận có sự tham gia đông đảo của binh lính. Người Trung Quốc có thói quen nói ai chưa trèo lên Vạn Lý Trường Thành thì không xứng đáng là hảo hán.

Chính vì lý do này mà Vạn Lý Trường Thành là một trong những địa điểm được người Trung Hoa tham quan nhiều nhất. Đây cũng là chiến tuyến ngăn cách người Hung Nô với người Trung Hoa. Nhiều người đã được gửi đến đây và chết ở mặt trận này. Vạn Lý Trường Thành đã chứng kiến nhiều bi kịch của con người và những cuộc chia ly đau đớn và bi thảm. Điều này làm chúng ta nhớ đến bốn câu trong bài thơ hay Lương Châu Từ của nhà thơ nổi tiếng Vương Hàn (Wang Han) ở thời nhà Đường:

Rượu bồ đào cùng với chén lưu ly

Muốn uống nhưng tỳ bà đã giục lên ngựa

Say khướt nằm ở sa trường, bác chớ cười

Xưa nay chinh chiến mấy ai trở về.

万里长城

Chúng ta cũng có thể nhớ đến truyền thuyết nổi tiếng nhất của Vạn Lý Trường Thành, đó là truyền thuyết về Mạnh Khương nữ (Meng Jiangnu). Nàng không ngần ngại đi bộ hơn 10.000 dặm để đi kiếm chồng mình, một thư sinh tên là Phạm Hỷ Lương (Fan Qiliang), người được hoàng đế Tần Thủy Hoàng gửi đến đèo Shanhaiguan trong ngày cưới để xây tường thành. Ở đó, nàng biết tin chồng mình đã chết vì đói lạnh và nàng không thể tìm thấy thi thể của chồng. Tuyệt vọng, cô khóc không ngừng suốt 3 ngày 3 đêm. Nước mắt của nàng làm xói mòn một phần thành lũy, giúp nàng tìm thấy thi thể chồng mình bị chôn vùi dưới bức tường. Sau khi chôn cất, nàng tự sát bằng cách lao mình xuống biển.

Ngày nay, ở Sơn Hải Quan (Hà Bắc, Hà Bắc) đã có dựng bàn thờ để tưởng nhớ bà. Cũng tại Sơn Hải Quan , tướng nhà Minh Ngô Tam Quế đã từ chối liên minh với Lý Tự Thành, thủ lĩnh nông dân khởi nghĩa vì lý do đơn giản là Lý Tự Thành cướp vợ thứ của Ngô Tam Quế là Trần Viên Viên nên mở cửa thành đầu quân Mãn Châu. Nhờ đó mới có sự khởi đầu của triều đại nhà Thanh (Mãn Châu).

Sự vững chắc của bức tường thành Vạn Lý này phần lớn là do việc sử dụng gạo nếp và canxi c ủa vôi trong sản xuất vữa vôi dùng để sửa chữa, phục hồi các công trình bằng đá cổ. Theo nhà nghiên cứu người Trung Quốc Zhang Bingjian của Đại học Chiết Giang, đó là Amylopectin (trong tiếng Việt gọi là vữa vôi), một chất có độ bền cơ học cao, giúp các công trình cổ của Trung Quốc, đặc biệt là Vạn Lý Trường Thành, bền vững trước thử thách của thời gian và động đất. Ông đã báo cáo phát hiện này trong bài báo đăng trên tạp chí Hoa Kỳ « Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2010, 132 (19), pp 6855–6861« . Điều này giải thích phong trào biểu tình của quần chúng ở miền nam Trung Quốc, nơi vào thời điểm đó có việc trưng dụng gạo một cách có hệ thống. Mục đích của việc này là dùng để làm vữa nếp và cung cấp thức ăn cho những người chịu có trách nhiệm trùng tu bức tường này vào thời nhà Minh.

Elle est constituée par un grand nombre de fortifications militaires et défensives dans différents endroits à la frontière nord de la Chine. Etant connue sous le nom chinois de « La longue muraille de dix mille li », elle commence à l’est à Shanhaiguan (Sơn Hải Quan), dans la province du Hebei (Hà Bắc) , et se termine à Jiayuguan (Gia Dục quan) dans la province orientale du Gansu (Cam Túc). Ayant plus de 5000 km, elle est le symbole de la Chine d’aujourd’hui. Les sections proches de Pékin ont été restaurées mais dans le Nord mais il reste encore des pans de murs chancelants. Ce grand ouvrage défensif fut construit à l’époque des Zhou au IXème siècle avant J.C. C’est pourquoi on y trouve non seulement des murs, de pistes cavalières mais aussi des tours de guet. C’est en 1987 que la Grande Muraille est classée au patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO . Elle est reconnue aussi comme le seul ouvrage construit par l’homme sur la terre que l’on puisse voir depuis la lune.

À l’époque des Royaumes Combattants, d’autres murs furent construits par les seigneurs de ces royaumes dans le but de défendre leur pays. Les historiens les qualifient de « murs pré-Qin ». Après l’unification du pays, on dit que dans son rêve, l’empereur des Qin Shi Huang Di aurait vu l’occupation de son empire par les barbares du Nord. Hanté par ce songe, il a chargé le général Meng Tian (Mộng Điềm) de relier les murs de ces six états conquis dans le but de contrer ces barbares. La dynastie des Ming a effectué les travaux de rénovation d’une durée approximative de 200 ans.

C’est la muraille des Ming qu’on voit aujourd’hui. C’est aussi l’avis de Arthur Waldron, auteur du livre intitulé « The Great Wall of China. From history to myth« . Pour ce dernier, la Muraille de Chine ne va pas plus loin au delà de la fin du XVème siècle. Elle va de Shanhaiguan (la passe Shanhai à l’est) et à Jiayuguan (la passe Jiayu à l’ouest) sur une longueur de 5660km. On peut dire que la construction de la grande muraille n’a jamais été interrompue complètement durant 2000 ans, de l’époque des Royaumes Combattants jusqu’à la dynastie des Qing. D’après les registres historiques, sa construction a mobilisé des centaines de milliers de paysans. De plus, durant les périodes de travaux intensifs, plus de 1,5 millions de personnes y sont engagées également sans oublier de noter aussi la participation massive de soldats. Les Chinois ont l’habitude de dire que celui qui n’est pas monté encore sur la Muraille de Chine ne mérite pas d’être un homme valeureux. »Bất đáo Trường Thành phi hảo hán (Chưa đến Vạn lý trường thành chưa phải là hảo hán« . C’est pour cette raison que la Muraille de Chine est l’un des sites les plus visités par les Chinois. Elle est aussi la ligne de front séparant les Barbares des Chinois. Beaucoup de gens ont été envoyés et péri sur ce front. La Muraille de Chine est témoin de plusieurs drames humains et de séparations douloureuses et tragiques. Cela nous fait rappeler les quatre vers du beau poème Liangzhu (Lương Châu Từ) du célèbre poète chinois Vương Hàn (Wang Han) à l’époque de la dynastie des Tang (Nhà Đường):

Bồ đào mỹ tửu dạng quang bôi

Dục ẩm tì bà mã thượng thôi

Túy ngọa sa trường quân mạc tiếu

cổ lai chinh chiến kỉ nhân hồi

Rượu bồ đào cùng với chén lưu ly

Muốn uống nhưng tỳ bà đã giục lên ngựa

Say khướt nằm ở sa trường, bác chớ cười

Xưa nay chinh chiến mấy ai trở về.

Il y a du vin rouge contenu dans ma coupelle étincelante et translucide

Malgré l’envie de le boire, je suis pressé de monter à cheval à cause du son du pipa

Ne ricanez pas si vous me voyez étendu et ivre mort sur le champ de bataille

Depuis toujours et de toutes les guerres, combien de gens en sont-ils revenus?

万里长城

On peut se remémorer aussi la plus célèbre légende de la Muraille de Chine, celle de la pleureuse Mạnh Khương nữ (Meng Jiangnu). Celle-ci n’hésite à marcher plus de 10.000 li pour aller chercher son mari, un étudiant nommé Fan Qiliang (Phạm Hỷ Lương) que l’empereur de Chine Shi Huang Di a envoyé le jour de son mariage à la passe de Shanhaiguan pour construire la muraille. Sur place, elle apprend le décès de son mari mort de faim et de froid et elle ne réussit pas à retrouver son corps. Désespérée, elle pleure incessamment durant 3 jours et 3 nuits. Ses larmes érodent une portion du rempart, ce qui lui permet de retrouver le corps de son mari enseveli sous la muraille. Après l’enterrement, elle se suicide en se jetant dans la mer.

Aujourd’hui, à Shanhaiguan (Sơn Hải Quan) (Hebei, Hà Bắc), il y a l’autel érigé en l’honneur de cette dame. C’est aussi à Shanhaiguan (Sơn Hải Quan) que le général chinois Wu Sanggui (Ngô Tam Quế) de la dynastie des Ming qui refuse de s’allier à Li Zicheng ( Lý Tự Thành ), le chef des rebelles paysans pour la simple raison que ce dernier s’empare de sa concubine Chen Yuanyuan (Trần Viên Viên), a ouvert la porte aux armées mandchoues. C’est ainsi que débute la dynastie des Qing.

La solidité de cette muraille est due en grande partie à l’utilisation du riz glutineux et du calcium de la chaux (vôi) dans la fabrication du mortier servant à la réparation et à la restauration des anciennes constructions en pierres et en roches. Selon le chercheur chinois Zhang Bingjian de l’université Zhejiang ( Chiết Giang), c’est l’Amylopectine (ou vữa en vietnamien ), une substance à haute résistance mécanique qui permet aux constructions anciennes chinoises, en particulier la Muraille de Chine, de résister à l’épreuve du temps et au séisme. Il a rapporté cette découverte dans son article publié dans le journal américain « Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2010, 132 (19), pp 6855–6861« . Cela donne l’explication au mouvement des protestations populaires ayant lieu au sud de la Chine où il y a en ce temps-là la réquisition systématique du riz. Celle-ci a pour but de servir à fabriquer le mortier glutineux et à nourrir les gens chargés de restaurer cette muraille à l’époque des Ming.

It consists of a large number of military and defensive fortifications in different locations on the northern border of China. Known by the Chinese name « The Ten Thousand Li Long Wall », it begins in the east at Shanhaiguan (Sơn Hải Quan), in Hebei Province (Hà Bắc), and ends at Jiayuguan (Gia Dục quan) in the eastern province of Gansu (Cam Túc). With a length of more than 5,000 km, it is the symbol of today’s China. The sections near Beijing have been restored, but in the north, there are still sections of shaky walls. This great defensive work was built during the Zhou period in the 9th century BC. Therefore, it contains not only walls, bridleways but also watchtowers. The Great Wall was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987. It is also recognized as the only man-made structure on Earth that can be seen from the moon.

During the Warring States period, other walls were built by the lords of these kingdoms to defend their countries. Historians refer to these as the « pre-Qin walls. » After the unification of the country, it is said that in his dream, the Qin emperor Shi Huang Di saw the occupation of his empire by the northern barbarians. Haunted by this dream, he commissioned General Meng Tian (Mộng Điềm) to connect the walls of these six conquered states in order to counter these barbarians. The Ming Dynasty carried out the renovation work, which lasted approximately 200 years.

This is the Ming wall that we see today. This is also the opinion of Arthur Waldron, author of the book « The Great Wall of China. From History to Myth. » For him, the Great Wall of China does not extend beyond the end of the 15th century. It runs from Shanhaiguan (the Shanhai Pass in the east) to Jiayuguan (the Jiayu Pass in the west) over a length of 5660 km. It can be said that the construction of the Great Wall was never completely interrupted for 2000 years, from the Warring States period to the Qing Dynasty. According to historical records, its construction mobilized hundreds of thousands of peasants. In addition, during periods of intensive work, more than 1.5 million people were also engaged in it, not to mention the massive participation of soldiers. The Chinese are accustomed to saying that he who has not yet climbed the Great Wall of China does not deserve to be a valiant man. « Bất đáo Trường Thành phi hảo hán (Chưa đến Vạn lý trường thành chưa phải là hảo hán ». This is why the Great Wall of China is one of the most visited sites by the Chinese. It is also the front line separating the Barbarians from the Chinese. Many people were sent and perished on this front. The Great Wall of China is witness to several human dramas and painful and tragic separations. This reminds us of the four lines of the beautiful poem Liangzhu (Lương Châu Từ) by the famous Chinese poet Vương Hàn (Wang Han) at the time of the Tang Dynasty (Nhà Đường):

Bồ đào mỹ tửu dạng quang bôi

Dục ẩm tì bà mã thượng thôi

Túy ngọa sa trường quân mạc tiếu

cổ lai chinh chiến kỉ nhân hồi

Rượu bồ đào cùng với chén lưu ly

Muốn uống nhưng tỳ bà đã giục lên ngựa

Say khướt nằm ở sa trường, bác chớ cười

Xưa nay chinh chiến mấy ai trở về.

There’s red wine in my sparkling, translucent bowl.

Despite the urge to drink it, I’m in a hurry to get on horseback because of the sound of the pipa.

Don’t sneer if you see me lying dead drunk on the battlefield.

Since the dawn of time, and from all the wars, how many people have returned?

万里长城

We can also recall the most famous legend of the Great Wall of China, that of the mourner Mạnh Khương nữ (Meng Jiangnu). She did not hesitate to walk more than 10,000 li to fetch her husband, a student named Fan Qiliang (Phạm Hỷ Lương) whom the Emperor of China Shi Huang Di sent on the day of his wedding to the Shanhaiguan pass to build the wall. There, she learned of the death of her husband who had died of hunger and cold and she was unable to find his body. Desperate, she cried incessantly for 3 days and 3 nights. Her tears eroded a portion of the rampart, which allowed her to find the body of her husband buried under the wall. After the burial, she committed suicide by throwing herself into the sea.

Today, in Shanhaiguan (Sơn Hải Quan) (Hebei, Hà Bắc), there is the altar erected in honor of this lady. It is also in Shanhaiguan (Sơn Hải Quan) that the Chinese general Wu Sanggui (Ngô Tam Quế) of the Ming dynasty, who refused to ally himself with Li Zicheng (Lý Tự Thành), the leader of the peasant rebels for the simple reason that the latter seized his concubine Chen Yuanyuan (Trần Viên Viên), opened the door to the Manchu armies. This is how the Qing dynasty began.

The strength of this wall is largely due to the use of glutinous rice and lime calcium (vôi) in the manufacture of mortar used for the repair and restoration of ancient stone and rock constructions. According to Chinese researcher Zhang Bingjian of Zhejiang University (Chiết Giang), it is Amylopectin (or vữa in Vietnamese), a substance with high mechanical resistance that allows ancient Chinese constructions, in particular the Great Wall of China, to withstand the test of time and earthquakes. He reported this discovery in his article published in the American journal « Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2010, 132 (19), pp 6855–6861 ». This explains the movement of popular protests taking place in southern China where at that time there was the systematic requisition of rice. This was used to make glutinous mortar and to feed the people responsible for restoring this wall during the Ming era.

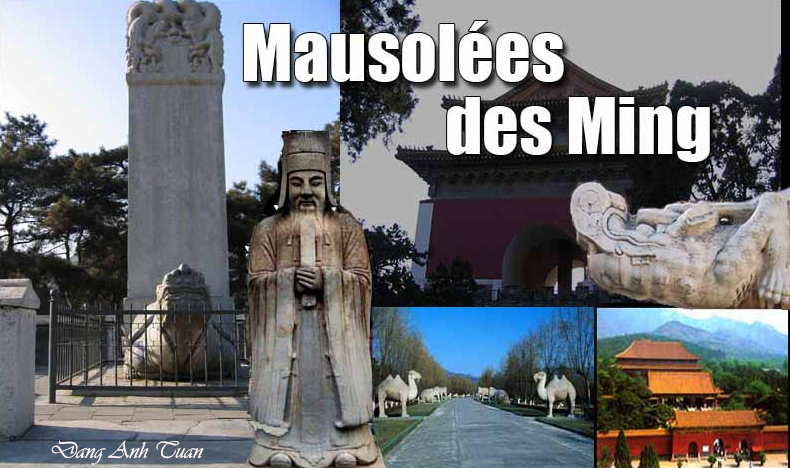

Thập Tam Lăng ( 13 Mausolées des Ming)

Thập Tam Lăng nhà Minh

Ming Shisan Ling

Mười ba lăng mộ nhà Minh nằm trong một thung lũng rộng phía nam núi Thiên Thọ, cách Bắc Kinh khoảng 42 cây số. Thung lũng này được chọn vì đáp ứng được tiêu chí về Phong Thủy. Nó được bao bọc ba mặt ở phía bắc nhờ có một dãy núi còn về phía nam nhờ sự hiện diên một khe hở để tránh được các thần linh ma quỷ từ gió bắc mang đến. Tổng cộng có 13 trong số 16 hoàng đế của nhà Minh, 23 hoàng hậu, một phi tần nhất phẩm cùng một số phi tần được an nghỉ tại nơi thung lũng bình yên này. Có ba vị hoàng đế nhà Minh không được chôn cất ở nơi nầy.

Nằm ở trung tâm nghĩa trang, thì có ngôi mộ của Chu Đệ (Trường Lăng) được xem là nổi bật với kích thước to lớn so với mười hai lăng mộ khác. Nó cũng là ngôi mộ đầu tiên được xây dựng ở đây với 60 cột gỗ lim cao có 12 mét và có đường kính 1 mét được đưa từ vùng rừng sâu của Vân Nam và Tứ Xuyên mang về Bắc Kinh và cũng là nơi tổ chức mọi hoạt động cúng tế. Còn các ngôi mộ khác của các hoàng đế nhà Minh thì được sắp xếp theo mô hình cây quạt xung quanh con đường chính thiêng liêng được gọi là « Thần Đạo » (Shendao)

Dọc hai bên của con đường dài này thì có 36 bức tượng bằng đá, 12 vị quan chức dân sự và quân sự, và 12 cặp động vật (sư tử, lạc đà, kỳ lân, voi, ngựa và con vật tưởng tượng). Ngôi mộ của Chu Đệ (Yong Le) vẫn còn nguyên vẹn. Nhưng chúng ta cũng biết rằng khi ông được an táng, có 16 phi tần cũng bị chôn sống. Phong tục dã man này đã bị bãi bỏ sau đó vào thế kỷ 15 dưới thời vua Minh Thần Tông (Vạn Lịch).

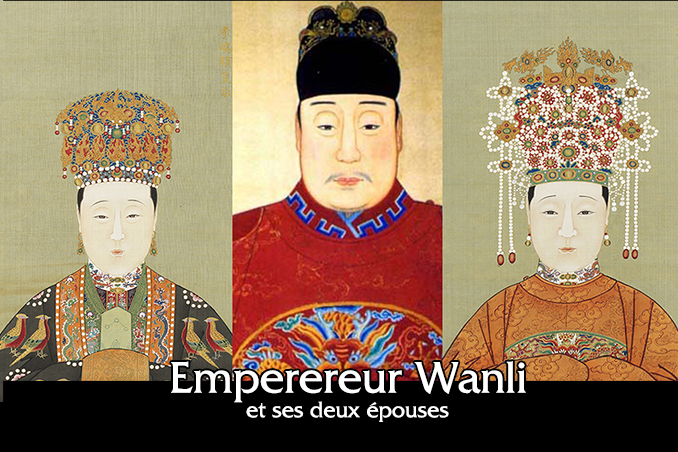

Khi còn sống, Hoàng đế Vạn Lịch bắt đầu xây dựng Định Lăng vào năm 1584. Điều này khiến nhà nước tốn một khoản tiền đáng kể. Không biết cấu trúc bên trong của ngôi mộ này, giáo sư Xia Nai, giám đốc Viện Khảo cổ học Bắc Kinh phải thực hiện cuộc khảo sát đầu tiên về Định Lăng vào năm 1956 và phát hiện ra ngôi mộ nầy chưa bao giờ bị xâm phạm. Chính nhờ một thẻ bài mới biết ra vị trí của cánh cửa ở trong bức tường với cơ chế bí mật được chôn sâu khoảng chừng 11 thước dưới lòng đất, ông mới thành công trong việc mở được ngôi mộ này cũng như các căn phòng phụ của nó.

Điều này dẫn đến sự tìm thấy phòng chôn cất của Vạn Lịch và hai bà hoàng hậu Tiêu Duẩn và Tiêu Cảnh. Ngoài ra còn có một số lượng lớn các đồ vật quý giá (trang sức bằng ngọc bích, gốm sứ ba màu, meiping (một lọại bình sứ ) vân vân ) trong 26 chiếc rương sơn mài màu đỏ tía được cất giử ở phòng phía sau cùng.

Điều này dẫn đến sự tìm thấy phòng chôn cất của Vạn Lịch và hai bà hoàng hậu. Ngoài ra còn có một số lượng lớn các đồ vật quý giá (trang sức bằng ngọc bích, gốm sứ ba màu, meiping (một lọại bình sứ ) vân vân ) trong 26 chiếc rương sơn mài màu đỏ tía được cất giử ở phòng phía sau cùng. Hiện tại, ngôi mộ duy nhất mà có thể du khách được truy cập đó lăng của Wanli (1573-1620) (Vạn Lịch). Bà hoàng hậu (Hiếu Đoan Văn Hoàng hậu) và bà hoàng quí phi (Hiếu Tĩnh Hoàng hậu) được chôn cất bên cạnh hoàng đế.

Cung điện dưới lòng đất nầy có diện tích 1195 thước vuông, sâu 27 mét. Nó được có 5 phòng: phòng phía trước, phòng trung tâm, phòng phía sau cũng như hai phòng bên. Nó được xây dựng bởi 30.000 công nhân sau sáu năm. Phòng trung tâm và phòng phía trước tạo thành một hành lang dài vuông góc với phòng phía sau. Tất cả các phòng đều được ngăn cách với nhau bằng một cánh cửa lớn bằng đá cẩm thạch màu trắng được trang trí bằng những tác phẩm điêu khắc tinh xảo. Ngoài ra còn có 3 chiếc ngai bằng đá cẩm thạch dành riêng cho người đã khuất ở gian giữa.

Ngoại trừ tấm bia mộ của Chu Đệ mà người kế vị ông để lại hơn 3000 chữ ca ngợi công đức của cha mình, chúng ta không tìm thấy chữ viết nào trên tấm bia của các ngôi mộ khác. Đây là một bí ẩn mà các nhà sử học cần phải giải quyết. Một số người cho rằng các hoàng đế nhà Minh đã bãi bỏ tục lệ này vì sợ bị hậu thế chỉ trích, chế giễu vì hành vi sai trái, trụy lạc. Một số người khác lại ủng hộ sự chấp nhận thái độ của Vũ Tắc Thiên thời nhà Đường bởi các hoàng đế nhà Minh. Bà nầy không để lại dấu vết gì cả để khỏi bị chỉ trích vì bà biết cách cư xử của mình không thể hoàn hảo.

Les tombeaux des Ming sont situés dans une large vallée au sud de la montagne Tianshou (Thiên Thọ) loin de Pékin à peu près de 42 kilomètres. Cette vallée a été choisie car elle répond aux critères de Fengshui (Phong Thủy). Elle est encadrée au nord sur ses trois côtés par une chaîne de montagnes et au sud par une ouverture, ce qui lui permet d’être protégée contre les mauvais esprits emmenés par les vents du Nord. Il y a en tout 13 des 16 empereurs des Ming, 23 impératrices, une concubine de premier rang et une douzaine de concubines impériales qui ont reposé dans cette vallée paisible. Trois empereurs des Ming ne sont pas enterrés ici.

Située au centre du cimetière, la sépulture de Yong Le (Trường Lăng) se fait remarquer par sa taille imposante par rapport aux douze autres mausolées avec 60 colonnes en bois de fer (gỗ lim) ayant 12 mètres de haut et un diamètre d’un mètre, ramenés de la région forestière de Yunnan et Sichuan jusqu’à Pékin. Elle est aussi la première à y être construite. Les autres tombeaux des empereurs des Ming sont disposés en éventail autour de la voie principale sacrée (Shendao). Cette longue allée est bordée de 36 statues de pierre, 12 dignitaires civils et militaires et 12 paires d’animaux (lions, chameaux, licornes, éléphants, chevaux et chimères). Le tombeau de Yong Le est resté inviolé. Mais on sait qu’au moment de son enterrement, 16 concubines furent emmurées vivantes à son côté. Cette coutume fut abolie après au XVème siècle.

De son vivant, l’empereur Wan Li commença à construire en 1584 son tombeau Dingling (tombeau de la tranquillité)(Định Lăng). Celui-ci coûte une somme considérable à l’état. Ignorant la structure interne de ce tombeau, le professeur Xia Nai, directeur de l’institut d’archéologie de Pékin, effectua le premier sondage sur le Dingling en 1956 et découvrit ce tombeau inviolé. Grâce à une tablette indiquant l’emplacement de la porte du mur au mécanisme secret enfoui à trente cinq pieds sous terre, il réussit à ouvrir ce tombeau ainsi que ses chambres annexes. Cela permet de retrouver la chambre funéraire de Wanli et de ses 2 impératrices Xiao Duan et Xiaojing. On trouve également un grand nombre d’objets précieux (parures de jade, des céramiques à trois couleurs, des meiping etc. ) dans les 26 coffres en laque pourpre rangés dans la salle du fond. Pour le moment, le seul tombeau accessible aux visiteurs est celui de Wanli ( 1573-1620) (Vạn Lịch en vietnamien). L’impératrice et la première concubine impériale (Hoàng Qúi Phi) furent enterrées à leur mort au côté de l’empereur.

Le palais souterrain d’une superficie de 1195 m2 se trouve à 27 mètres de profondeur. Il est constitué de 5 salles: la salle antérieure, la salle centrale, la salle postérieure ainsi que deux salles latérales. Il a été construit par 30.000 ouvriers au bout de six ans. La salle centrale et la salle antérieure forment un long couloir directement perpendiculaire à la salle de fond. Toutes les salles sont isolées les unes des autres par une grande porte en marbre blanc décorée de fines sculptures. On trouve aussi 3 trônes en marbre réservés pour les défunts dans la chambre centrale.

Excepté le stèle du tombeau de Yong Le sur lequel son successeur a laissé plus de 3000 mots vantant les mérites et les vertus de son père, on ne trouve aucune écriture sur les stèles des autres tombeaux. C’est une énigme à élucider pour les historiens. Certains pensent que les empereurs des Ming abolirent cette tradition par peur d’être critiqués et ridiculisés par la postérité à cause de leur mauvaise conduite et de leur débauche. D’autres penchent en faveur de l’adoption de l’attitude de Wu Ze Tian (Vũ Tắc Thiên) de la dynastie des Tang par les empereurs des Ming. Celle-ci ne laisse aucune trace écrite afin de ne pas être critiquée car elle savait que son comportement n’était pas irréprochable.

The Ming Tombs are located in a wide valley south of Tianshou Mountain (Thiên Thọ), about 42 kilometers from Beijing. This valley was chosen because it meets the criteria of Fengshui (Phong Thủy). It is framed on three sides by a mountain range to the north and by an opening to the south, which allows it to be protected against evil spirits carried by the north winds. In all, 13 of the 16 Ming emperors, 23 empresses, one first-rank concubine, and a dozen imperial concubines were laid to rest in this peaceful valley. Three Ming emperors are not buried here.

Located in the center of the cemetery, Yong Le’s tomb (Trường Lăng) stands out for its imposing size compared to the twelve other mausoleums, with 60 ironwood columns (gỗ lim) 12 meters high and one meter in diameter, brought from the forest region of Yunnan and Sichuan to Beijing. It was also the first to be built there. The other tombs of the Ming emperors are arranged in a fan shape around the main sacred path (Shendao). This long path is lined with 36 stone statues, 12 civil and military dignitaries and 12 pairs of animals (lions, camels, unicorns, elephants, horses and chimeras). Yong Le’s tomb has remained inviolate. But it is known that at the time of his burial, 16 concubines were walled up alive beside him. This custom was abolished after the 15th century.

During his lifetime, Emperor Wan Li began building his Dingling Tomb (Tomb of Tranquility) (Định Lăng) in 1584. It cost the state a considerable amount of money. Unaware of the internal structure of this tomb, Professor Xia Nai, director of the Beijing Institute of Archaeology, carried out the first survey of the Dingling in 1956 and discovered this inviolate tomb. Thanks to a tablet indicating the location of the door of the wall with the secret mechanism buried 35 feet underground, he succeeded in opening this tomb as well as its annex chambers. This allows us to find the burial chamber of Wanli and his two empresses Xiao Duan and Xiaojing. A large number of precious objects (jade ornaments, three-color ceramics, meiping, etc.) are also found in the 26 purple lacquer chests stored in the back room. Currently, the only tomb open to visitors is Wanli Tomb (1573-1620) (Vạn Lịch in Vietnamese). The empress and the first imperial concubine (Hoàng Qúi Phi) were buried at the emperor’s side upon their death.

The underground palace, covering an area of 1,195 square meters, is located 27 meters underground. It consists of five rooms: the front room, the central room, the rear room, and two side rooms. It was built by 30,000 workers over a period of six years. The central room and the front room form a long corridor directly perpendicular to the rear room. All the rooms are separated from each other by a large white marble door decorated with fine carvings. There are also three marble thrones reserved for the deceased in the central chamber.

Apart from the stele of Yong Le’s tomb, on which his successor left more than 3,000 words extolling the merits and virtues of his father, no writings are found on the stelae of the other tombs. This remains a mystery for historians to solve. Some believe that the Ming emperors abolished this tradition out of fear of being criticized and ridiculed by posterity for their misconduct and debauchery. Others believe that the Ming emperors adopted the attitude of Wu Ze Tian (Vũ Tắc Thiên) of the Tang Dynasty. She left no written records so as not to be criticized because she knew her behavior was not beyond reproach.

Kinkaku-ji (Kim Các Tự)

Kinkaku-ji (Kim Các Tự)

Version française

Được biết đến với cái tên quen thuộc là Kinkaku-ji, ngôi chùa Rokuon-ji (Lộc Uyển Tự) này là một trong những viên ngọc quý của cố đô Kyoto. Trái ngược với sự đơn giản mà chúng ta thường thấy trong kiến trúc Phật giáo Nhật Bản, Kinkaku-ji là một tòa nhà ba tầng với những bức tường dát vàng đặt giữa một hồ nước. Điều này cho phép toà nhà phản chiếu ánh sáng vàng trên mặt nước hồ quanh năm trong một khung cảnh tráng lệ và thanh tịnh. Trên đỉnh tòa nhà rực rỡ này còn có một con phượng hoàng bằng đồng.

Trong ngôi nhà vàng này, chúng ta tìm thấy ba phong cách kiến trúc, tầng trệt tương ứng với phong cách của các cung điện ở thời Heian (794 – 1185), tầng một là phong cách của các ngôi nhà của các võ sĩ và tầng trên cùng là phong cách của các ngôi chùa thiền. Ban đầu, vị tướng quân thứ ba Yoshimitsu của gia tộc Ashikaga (1358-1408), một đệ tử nhiệt thành của thiền sư Soseki, muốn biến nơi này thành nơi ở riêng trong thời gian ông từ giã cuộc sống công cộng. Khi ông qua đời, con trai ông là Yoshimochi quyết định biến nơi này thành một ngôi chùa Thiền tông cho trường phái Rinzai và đặt tên là « Rokuon-ji« . Sau đó nó bị phá hủy nhiều lần bởi hỏa hoạn. Lần trùng tu cuối cùng có niên đại năm 1955 là bản sao giống hệt như thưở ban đầu. Đây là di sản thế giới được cơ quan UNESCO công nhận từ năm 1994 và được xem là ngôi chùa Phật giáo săn đón một số lượng lớn du khách mỗi năm đến từ Nhật Bản.

Etant connu sous son nom usuel de Kinkaku-ji, ce temple Rokuon-ji (Lộc Uyển Tự) est l’un des bijoux de l’ancienne capitale de Kyoto. Contrairement à la simplicité qu’on est habitué à voir dans l’architecture bouddhique japonaise, Kinkaku-ji est une bâtisse à trois étages dotée des parois recouvertes de feuilles d’or trônant au milieu d’un étang. Cela lui permet de refléter tout le long de l’année sur la surface de l’eau sa lumière dorée dans un cadre magnifique et serein. Au sommet de cette bâtisse éblouissante se trouve un phénix en cuivre. On retrouve dans ce pavillon d’or trois styles d’architecture, le rez-de-chaussée correspondant au style des palais de l’époque Heian (794 – 1185), le premier étage à celui des maisons des samouraïs et le dernier étage à celui des temples zen. À l’origine, le troisième shogun Yoshimitsu de la famille Ashikaga (1358-1408), disciple fervent du moine zen Soseki veut faire de ce lieu une demeure privée lors de son retrait de la vie publique. À sa mort, son fils Yoshimochi décide de transformer l’endroit en temple zen pour l’école Rinzai et le nomme « Rokuon-ji ». Puis il est détruit plusieurs fois par les flammes. La dernière restauration datant de 1955 est la copie absolument conforme de l’ancien pavillon. Il est inscrit au Patrimoine mondial de l’Unesco depuis 1994 et il est considéré comme le temple bouddhiste accueillant un grand nombre de visiteurs par an du Japon.

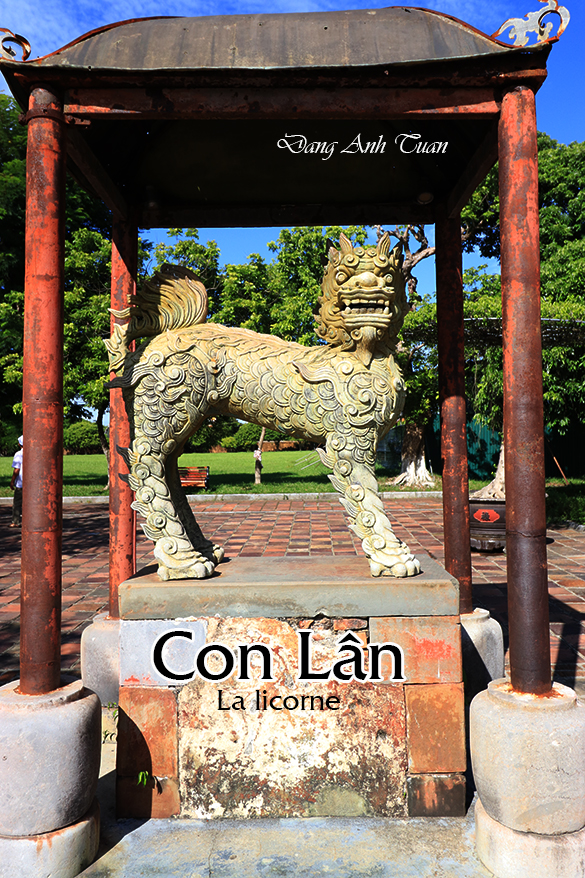

Con Lân (La licorne)

Con Lân (La licorne)

Lân là con linh vật đứng hàng thứ nhì trong bốn con vật có sức mạnh siêu phàm hay tứ linh (long, lân, qui, phụng). Trong văn hóa Việt nam, chúng ta thường bị lầm lẫn giữa con kỳ lân với con nghê. Đặc điểm để phân biệt giữa nghê và lân là ở bộ móng, nghê mang móng vuốt còn kỳ lân mang móng guốc. Lân thường xuất hiện ở đình, chùa, đền, miếu hay những công trình kiến trúc nghệ thuật. Theo nhà nghiên cứu việt Đinh Hồng Hải thì Lân có nguồn gốc Trung Hoa, một linh vật tưởng tượng ngoại nhập. Thật sự khi gọi kỳ lân, tức là nói đến một cặp: con đực gọi là kỳ và lân là con cái. Khi du nhập vào văn hóa việt thì người Việt quên đi « con kỳ » mà chỉ kêu là lân thôi. Chỉ có những vị quân vương hiền minh mới xứng đáng được trông thấy nó. Ở Sân Đại Triều Nghi trước Điện Thái Hòa của Tử Cấm Thành (Huế) có hai con lân được đặt ở hai góc sân mang ý nghĩa thời thái bình mà còn biểu tượng nhắc nhở đến sự uy nghiêm giữa chốn triều đình. Lân còn là con vật tiêu biểu báo điềm lành. Nó còn có khả năng nhận ra được người hiền lành và kẻ gian trá. Người dân Việt thường biết nó qua múa lân sư được biểu diễn trong các dịp lễ hội, đặc biệt là Tết Nguyên Đán, Tết Trung Thu hay khánh thành cửa hàng mới vì loại thú nầy tượng trưng cho thịnh vượng và hạnh phúc. Còn trong đạo Phật, nó là hiện thân của bát nhã tức là trí tuệ tối cao hay gíác ngộ.

Version française

La licorne figure au deuxième rang parmi les quatre animaux sacrés aux pouvoirs surnaturels (dragon, licorne, tortue et phénix). Dans la culture vietnamienne, on est habitué à confondre souvent la licorne avec le chien-lion (con nghê). La caractéristique permettant de faire la distinction entre ce dernier et la licorne se retrouve dans les ongles. Le chien-lion possède des griffes tandis que la licorne a des sabots. Les licornes sont visibles souvent dans les maisons communales, les pagodes, les temples, les sanctuaires ou les œuvres d’art architecturales. Selon le chercheur vietnamien Đinh Hồng Hải, la licorne (ou Lân) est d’origine chinoise. Il s’agit d’une mascotte imaginaire importée de l’étranger. En fait, lorsqu’on évoque la licorne, on se réfère souvent à un couple d’animaux : le mâle est connu sous le nom « kỳ » tandis que la femelle s’appelle « lân ». Au moment de l’introduction de la licorne dans la culture vietnamienne, on n’a gardé que la femelle (Lân). Seuls les monarques sages sont dignes de pouvoir la voir. Dans l’esplanade des Grands Saluts devant le somptueux palais de la suprême harmonie (Điện Thái Hoà) de la Cité pourpre interdite (Huế), il y a deux licornes placées dans deux coins différents pour marquer non seulement la période de paix mais aussi le caractère hiératique de la cour impériale. La licorne est un animal de bon augure. Elle est capable de discerner la probité et la malhonnêteté chez un homme. Les Vietnamiens ont l’habitude de la connaître grâce à la danse de la licorne à l’occasion des fêtes importantes (Le Nouvel An, la fête de la Mi-Automne, l’inauguration de la nouvelle boutique etc.) car elle est le symbole de la prospérité et du bonheur. Quant au bouddhisme, la licorne est l’incarnation de l’esprit intuitif de la Prajna (l’intelligence suprême ou l’illumination).

Hôtel des Invalides (Điên Invalides)

Hôtel des Invalides

Le Dôme reste le bâtiment le plus élevé de Paris jusqu’à l’érection de la tour Eiffel. Il a été conçu par l’architecte Jules Hardouin-Mansart sous le règne de Louis XIV. Les nombreuses dorures du dôme rappellent que le Roi-Soleil avait ordonné la construction de l’Hôtel des Invalides par édit afin d’accueillir les anciens soldats de son armée. C’est aussi l’endroit où a été déposé le cercueil de l’empereur Napoléon 1er de la France.

Mái vòm Invalides vẫn là tòa nhà cao nhất ở Paris cho đến khi tháp Eiffel được dựng lên. Nó được thiết kế bởi kiến trúc sư Jules Hardouin-Mansart dưới thời ngự trị của vua Louis XIV. Các vàng thép được trông thấy trên mái vòm nhắc lại vua Mặt Trời ra chỉ thị cho phép xây dựng khách sạn Invalides qua một sắc lệnh để tiếp nhận các cựu binh trong quân đội. Đây cũng là nơi an nghỉ của Nã Phá Luân Đại Đế của Pháp quốc.