Con số Âm Dương của người Việt

Người Việt thường nói : sống chết đều có số cả . Ði buôn có số, ăn cỗ có phần. Trong cuộc sống hằng ngày, mặc quần áo hay mang giày cũng có kích thước. Khác hẳn người Hoa thích số chẵn (hay số Dương), người dân Viêt thường dùng số lẻ thay vì số dương đấy. Bởi vậy thường thấy trong thành ngữ hay tục ngữ Việt có sự trọng dụng số lẻ như sau : ba mặt một lời, ba hồn bảy vía, Ba chìm bảy nổi chín lênh đênh, năm thê bảy thiếp, năm lần bảy lượt, năm cha ba mẹ, ba chóp bảy nhoáng, Môt lời nói dối , sám hối 7 ngày, Một câu nhịn chín câu lành vân vân …hay là những con số tăng lên nhiều lần từ số 9 mà ra chẳng hạn : 18 (9×2) đời Hùng Vương, 27 (9×3) đại tang 3 năm ( 27 tháng), 36 (9×4) phố phường Hànội vân vân. Cũng đừng quên rằng người Việt rất xem trọng con số 5 và số 9 vì hai con số lẻ nầy có một vai trò rất quan trọng. Con số 5 là con số thần bí nhất vì tất cả đều khởi đầu từ con số 5 nầy ra cả. Trời Đất có được vạn vật phát sinh từ 5 yếu tố cơ bản qua 5 trạng thái: Mộc, Hỏa, Thổ, Kim và Thủy mà thường gọi là ngũ hành.

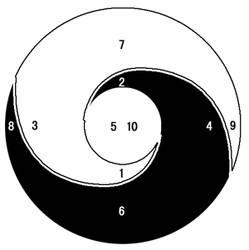

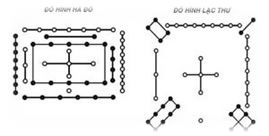

Lạc Thư Hà Đồ

Con số 5 được đặt ở trung tâm của Lạc Thư Hà Đồ, hai bức đồ nguồn góc của sự biến đổi và vận hành của Âm Dương Ngũ Hành. « Đất » là yếu tố đuợc gắn liền với con số 5 và từ ở trung tâm đất mà ra, người nông mới tìm thấy ra được các phương hướng chủ yếu. Chính nhờ vậy mà ở trung tâm con người mới quản lý được vạn vật vạn loại cùng 4 phương trời. Bởi vậy ở trong xã hội phong kiến, vị trí nầy thường dành cho vua. Chính vua là người cai trị quần chúng. Vì thế con số 5 thuộc về sơ hữu của vua cũng như màu vàng riêng tư, màu biểu tượng của Đất. Bởi vậy các vua chúa ở thời đại phong kiến (Việtnam và Trung Hoa) thường chọn màu nầy cho y phục.

Ngoài vị trí trung tâm mà con người giữ, mỗi con vật được gắn liền với mỗi phương: qui với phương bắc, phụng thì phương nam, còn phương đông dành cho rồng (hay long) và sau cùng phương tây với hổ (cọp). Cũng không có gì ngạc nhiên trong bốn con vật nầy đã có 3 con sống ở vùng nước mà đời sống nông nghiệp là chính. Đó là vùng đất của đại tộc Bách Việt. Luôn cả con rồng thường hung hăng dữ tợn trong các nền văn hóa khác thì nó rất hiền lành dễ thương qua trí tưởng tượng của những bộ tộc hiền hòa Bách Việt. Con số 5 thường được gọi là « Tham Thiên Lưỡng Địa« (hay là ba Trời hai Ðất ) trong thuyết Âm Dương. Với tỷ lệ chí lí về sự tương xứng của Âm và Dương , có được nó từ sự tập hợp của con số 3 và con số 2 hơn là đến từ con số 4 và con số 1 vì với hai con số nầy , thì nhận thấy con số dương 1 hoàn toàn bị số âm 4 lấn áp và chiếm ưu thế. Còn ngược lại với con số 2 và và số 3 thì sự chiếm ưu thế của con số 3 không nhiều chi cho mấy cho nên sự vận động của vũ trụ có vẻ hài hoà hơn và gần như hoàn chỉnh. Thưở xưa, ngày thứ năm, ngày 14 (1+4) hay ngày 23 (2+3) trong tháng là những ngày dành cho vua xuất hành. Cũng là những lúc không được buôn bán khi vua đi dạo. Chính vì thế người dân Việt hôm nay vẫn còn kiêng cữ những ngày đó, theo tục lệ dân gian ông bà, việc xây cất nhà cửa, đi buôn hay đi xa. Bởi vậy người ta thường nghe nói:

Chớ đi ngày bảy chớ về ngày ba

Mồng năm, mười bốn hai ba

Đi chơi cũng lỗ nữa là đi buôn

Mồng năm mười bốn hai ba

Trồng cây cây đỗ, làm nhà nhà xiêu

Con số 5 thường được nhắc đến nhiều trong ẩm thực của người Việt. Nước mắm là loại gia vị phổ biến nhất của người Việt. Trong việc chế biến pha làm nước mắm dùng thì người ta nhận thấy có sự hiện diện cuả ngũ vị được sắp xếp theo ngũ hành: mặn với nước mắm từ chất muối ra, đắng từ vỏ chanh, chua từ nước chanh hay nước dấm, cay với ớt thái khoanh nhỏ và ngọt với đường bột. Ngũ vị nầy mặn, đắng, chua, cay, ngọt tìm thấy ở trong nước mắm phù hợp với ngũ hành của lý thuyết Âm Dương ( Thủy , Hỏa , Mộc , Kim Thổ ). Cũng như canh chua cá của người Nam Bộ cũng có ngũ vị như sau: chua với me hay dấm, ngọt với những lát khớm hay thơm, cay với ớt tươi , mặn với nước mắm và đắng với đậu bắp hay bông so đũa. Truớc khi dùng, người ta thêm vài loại rau thơm như ngò gai, rau om. Đây là đặc tính món canh chua của người Nam Bộ khác biệt với những món canh chua ở các vùng khác của Việtnam.

Chúng ta cũng không quên nhắc bánh chưng mà chúng ta thường đựợc ăn trong những ngày Tết. Đây là món quà qúi báu mà tổ tiên ta truyền lại cho dân tộc qua nhiều thiên kỷ. Đây cũng là bằng chứng cụ thể nói lên lý thuyết Âm Dương ngũ hành thuộc về của đại tộc Bách Việt (mà trong đó có bộ tộc Lạc Việt) chớ không phải của Hán tộc vì trong công thức làm bánh chưng thì có quy luật ngũ hành tương sinh như sau:

Hỏa sinh Thổ

Thổ sinh Kim.

Kim sinh Thủy

Thủy sinh Mộc

Mộc sinh Hỏa

Chính giữa của bánh chưng lúc nào cũng có nhân thịt màu đỏ cả (Hỏa) rồi sau đó nhân được bao kín xung quanh với đậu xanh lột vỏ nấu chín màu vàng tượng trưng cho Đất . Kế đó đổ thêm một lớp gạo trắng phía trên phần nhân tượng trưng cho Kim rồi đi hấp với nước sôi (Thủy) để sau cùng bánh nó được chín và nhuộm màu xanh của lá dừa (tượng trưng cho Mộc hay cây).

Có một loại bánh mà người dân Việt không thể thiếu trong lễ cưới. Đó là bánh xu xê hay phu thê. Bánh nầy có hình tròn ở trong nhưng được gói với lá chuối bên ngoài với hình khối của nó màu xanh và buột với dây băng màu đỏ. Như vậy cho thấy Dương (hỉnh tròn của bánh) nằm trọn trong Âm qua hình khối. Bánh nầy thường làm với bột bán, thơm mùi lá dứa và có vừng màu đen. Giữa bánh thường có nhân đậu xanh hấp chín (màu vàng) trộn chung với mứt dừa được nạo nhỏ và hạt sen (màu trắng) tựa như kem mà thường thấy trong bánh của các vua (hay galette des rois). Tính chất bột của bánh rất dính nói lên đây dây tơ hồng buộc chặt vợ chồng. Bánh nầy biểu tượng tình yêu hoàn hảo, keo sơn bền vững và son sắt phù hợp với Trời Đất và ngũ hành qua 5 màu sắc (xanh, đỏ, đen, vàng và trắng).

Từ ngày chàng bước xuống ghe

Sóng bao nhiêu đợt bánh phu thê rầu bấy nhiêu.

Lầu Ngũ Phụng

Ngọ Môn năm cửa chín lầu

Một lầu vàng, tám lầu xanh, ba cửa thẳng, hai cửa quanh

Bên đông và bên tây cửa thành có hai cửa thường được gọi là Hiển Đức Môn và Hiền Nhân Môn thì dành cho các ông và phụ nữ.

Còn con số 9 là con số dương (hoăc số lẻ). Nó tượng trưng cho quyền lực của khí dương ở tột đĩnh khó mà ai đạt được lắm. Bởi vậy hoàng đế thường dùng nó để biểu dương quyền lực. Hoàng đế thường bước lên chín bậc nơi mà có ngai vàng để ngự trị . Nghe nói Tử Cấm Thành ở Huế cũng như ở Bắc Kinh có đến 9999 căn phòng. Cũng nên nhắc lại người xây cất Tử Cấm Thành ở Bắc Kinh là người Việtnam, ông Nguyễn An bị lưu đày từ thưở nhỏ vào thời nhà Minh. Hoàng đế cũng như tất cả cung điện đều hướng về phía nam nơi có khí dương, để có thể thụ hưởng được sinh khí của mặt trời nhất là hoàng đế là con của Trời.

Ở Huế, có chín cái đỉnh bằng đồng, đặt ở trước sân Thế miếu trong hoàng thành Huế. Số 9 còn thấy qua như 9 mái nhà của lầu Ngũ phụng, 9 khẩu thần công (hay là Cửu vị thần công) xưa đặt trước Ngọ Môn nay dời về vị trí hiện nay hay là 9 nhánh của sông Cửu Long vân vân…Qua chuyện Sơn Tinh Thủy Tinh, nhớ lại trong sính lể mà vua Hùng Vương thứ 18 (2×9) đưa ra những điều kiện để có thể cưới được công chúa Mị Nương thì phải có voi 9 ngà, gà chín cựa, ngựa 9 hồng mao. Con số 9 nầy còn tượng trưng Trời mà ngày sinh của Trời là ngày thứ chín của tháng hai.

Tuy không bằng sô 5 và số 9 nhưng con số 3 cũng được trọng dụng thông thường trong đời sống dân Việt qua những thành ngữ chẳng hạn, muốn nói đến một giới hạn hay mức độ nào không thể vượt qua thì người Việt thường có thói quen nói:

Không ai giàu ba họ, không ai khó ba đời.

Nhất quá Tam. (Tối đa là 3 lần trở lại)

Uốn Ba tấc lưỡi (đắn đo trước khi nói) , Ba trợn (trợn quá mức) , Ba phải (kẻ xu thời quá mức ) , Ba đá (thiếu trách nhiệm quá mức) vân vân …

Số 3 còn dùng để ám chỉ một việc gì hay số lượng dùng không quan trọng:

Ăn sơ sài ba hột, Ăn ba miếng, Sách ba xu, Ba món ăn chơi vân vân …

Con số 3 cũng như con số 7 thường được nói đến rất nhiều trong văn chương Việt Nam. Thành ngữ « Bảy nổi ba chìm với nước non » mà Hồ Xuân Hương dùng trong bài thơ: « Bánh trôi nước »:

Thân em vừa trắng lại vừa tròn

Bảy nỗi ba chìm với nước non…

nói lên những nỗi gian truân của phụ nữ thời đó sống ở trong một xã hội phong kiến Khổng giáo hay là

Ba hồi trống giục đù cha kiếp

Một nhát gươm đưa, đéo mẹ đời.

đây là những lời cuối của Cao Bá Quát, một thi sỹ lỗi lạc nhưng vì có tinh thần độc lâp, yêu chuông công bình và tự do mà bị giết trong cuộc khởi nghĩa (giặc Châu Chấu) chống triều Nguyễn dưới thời vua Tư Đức.

Nếu lý thuyết Âm Dương Ngũ Hành vẫn tiếp tục ám ảnh người dân Việt bởi tính cách thần bí và khó hiểu của nó nhưng nó lúc nào cũng là một cách suy nghĩ và một lối sống mà phần đông người dân Việt quen giữ thường ngày để thực hành những việc thông thường trong cuộc sống và tôn trọng truyền thống của tổ tiên.

[Trở về Âm Dương trong đời sống của người dân Việt]

Bibliographie

-Xu Zhao Long : Chôkô bunmei no hakken, Chûgoku kodai no nazo in semaru (Découverte de la civilisation du Yanzi. A la recherche des mystères de l’antiquité chinoise, Tokyo, Kadokawa-shoten 1998).

-Yasuda Yoshinori : Taiga bunmei no tanjô, Chôkô bunmei no tankyû (Naissance des civilisations des grands fleuves. Recherche sur la civilisation du Yanzi), Tôkyô, Kadokawa-shoten, 2000).

-Richard Wilhelm : Histoire de la civilisation chinoise 1931

-Nguyên Nguyên: Thử đọc lại truyền thuyết Hùng Vương

– Léonard Rousseau: La première conquête chinoise des pays annamites (IIIe siècle avant notre ère). BEFO, année 1923, Vol 23, no 1

-Paul Pozner : Le problème des chroniques vietnamiennes., origines et influences étrangères. BEFO, année 1980, vol 67, no 67, p 275-302

-Dich Quốc Tã : Văn Học sữ Trung Quốc, traduit en vietnamien par Hoàng Minh Ðức 1975.

-Norman Jerry- Mei tsulin (1976) : The Austro asiatic in south China : some lexical evidence, Monumenta Serica 32 :274-301

-Henri Maspero : Chine Antique : 1927.

-Jacques Lemoine : Mythes d’origine, mythes d’identification. L’homme 101, paris, 1987 XXVII pp 58-85

-Fung Yu Lan: A History of Chinese Philosophy ( traduction vietnamienne Đại cương triết học sử Trung Quốc” (SG, 1968).68, tr. 140-151)).

-Alain Thote: Origine et premiers développements de l’épée en Chine.

-Cung Ðình Thanh: Trống đồng Ðồng Sơn : Sự tranh luận về chủ quyền trống

đồng giữa h ọc giã Việt và Hoa.Tập San Tư Tưởng Tháng 3 năm 2002 số 18.

-Brigitte Baptandier : En guise d’introduction. Chine et anthropologie. Ateliers 24 (2001). Journée d’étude de l’APRAS sur les ethnologies régionales à Paris en 1993.

-Nguyễn Từ Thức : Tãn Mạn về Âm Dương, chẳn lẻ (www.anviettoancau.net)

-Trần Ngọc Thêm: Tìm về bản sắc văn hóa Việt-Nam. NXB : Tp Hồ Chí Minh Tp HCM 2001.

-Nguyễn Xuân Quang: Bản sắc văn hóa việt qua ngôn ngữ việt (www.dunglac.org)

-Georges Condominas : La guérilla viêt. Trait culturel majeur et pérenne de l’espace social vietnamien, L’Homme 2002/4, N° 164, p. 17-36.

-Louis Bezacier: Sur la datation d’une représentation primitive de la charrue. (BEFO, année 1967, volume 53, pages 551-556)

-Ballinger S.W. & all: Southeast Asian mitochondrial DNA Analysis reveals genetic continuity of ancient Mongoloid migration, Genetics 1992 vol 130 p.139-152....