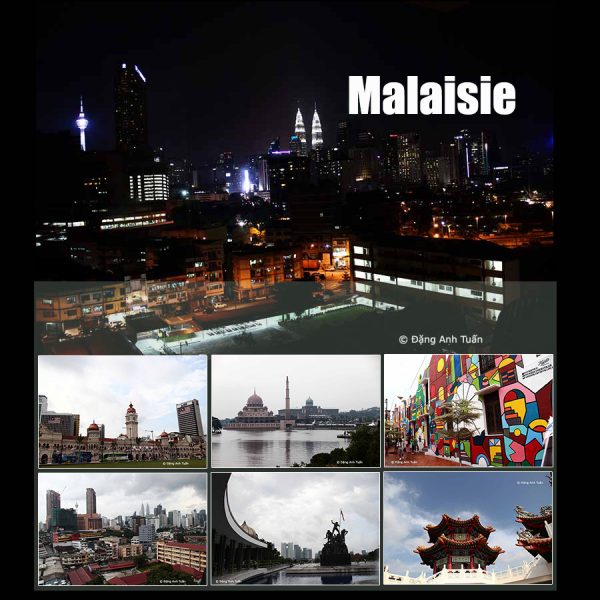

- Kuala Lumpur

- Malacca

- Putrajava

- Batu

Galerie des photos du Vietnam

Phủ Thiên Trường

Đây là một quần thể kiến trúc và lịch sử dành để thờ các vua nhà Trần và các quan có công phù tá. Nằm trên quốc lộ số 10 trong tỉnh Nam Định, đền nầy được xây cất lại năm 1695 trên nền thái miếu cũ được gọi là phủ Thiên Trường mà quân xâm lược nhà Minh phá hủy vào thế kỷ 15. Cũng ở nơi nầy mà phát tích vương triều nhà Trần. Các vua nhà Trần tạm về nơi nầy để lánh nạn trong thời gian chống giặc Nguyên Mông của Hốt Tất Liệt.

C’est un ensemble architectural et historique remarquable dédié au culte des rois de la dynastie des Trần et de leurs célèbres serviteurs. Situé à la route nationale n°10 dans la province de Nam Định, il fut reconstruit en 1695 sur l’emplacement de l’ancien temple royal connu sous le nom « Phủ Thiên Trường » détruit complètement par les envahisseurs chinois (les Ming) au XVème siècle. C’est ici qu’est née la dynastie des Trần. Les rois des Trần y trouvaient refuge durant la guerre contre les Mongols de Kubilai Khan.

Kiến Trung Palace

Version vietnamienne

Version française

Located at the northern end of the sacred axis crossing the center of the Purple Forbidden City, the Kiến Trung Palace is an architectural work built by King Khải Định between 1921 and 1923. It is also the first building where there is a combination of European style, including both French architecture and Italian Renaissance architecture, and traditional Vietnamese architecture. The facade of this palace is richly decorated with colorful ceramic motifs and fragments, thus bearing the imprint of the identity of the royal court of the Nguyễn dynasty. On the advice of several French architects and engineers and the Ministry of Public Works, this palace, responding to the aesthetic taste of the time, was completed in just two years, from 1921 to 1923, on the former site where two other architectural works previously known successively as Minh Viễn Lâu (1827) and Du Cửu Lâu (1913) had stood. According to the Hue Monuments Conservation Center, it has been known as Kiến Trung (Kiến « erected » and Trung « straight, no deformation« ).

This palace was considered the residence of the last two kings of the Nguyễn dynasty: Khải Định and Bảo Đại. It was here that King Khai Dinh passed away on November 6, 1925. During the reign of King Bảo Đại, the palace and its interior were renovated in a Western style, including the bathroom. It was also in this palace that Queen Nam Phương gave birth to the crown prince Bảo Long (January 4, 1936). During the Vietnam War, this palace was completely destroyed along with other residences of the Forbidden City. Since 2013, the Huế Monuments Conservation Center has begun launching the restoration project of the Kiến Trung palace. This project was implemented from February 2019 and completed in August 2023 with a total cost of more than 123 billion đồng.

Today, the Kiến Trung palace has become the favorite place for all tourists when visiting the Forbidden Purple City.

Temple Đô (Lý Bát Đế)

This Đô Temple was built in the year 1030 during the return of King Lý Thái Tông to celebrate the anniversary of the death of his father Lý Công Uẩn (Lý Thái Tổ). However, this building was completely destroyed during the colonial period. That is why in 1989 the Vietnamese government decided to restore it based on the still preserved historical documents. In front of its entrance gate is a water pavilion erected on a large pond in the shape of a half-moon, which once connected to the Tiêu Tương River that no longer exists today. This historic architectural complex is dedicated to the worship of the 8 kings of the Lý dynasty, which the famous historian Ngô Sĩ Liên described as a dynasty of clemency in the collection entitled « The Complete Historical Records of Đại Việt » (Ðại Việt Sử Ký toàn thư) (1697).

According to the popular saying, in the work « Florilegium of the Thiền Garden (Thiền Uyển Tập Anh) » there is a kệ (or gâtha) alluding to the 8 kings of the Lý dynasty, which is attributed either to the disciple of the patriarch monk Khuôn Việt, Đa Bảo, or to the monk Vạn Hạnh as follows:

The word Bát with the Lý family

Một bát nước công đức

Tùy duyên hóa thế gian

Sáng choang còn soi đuốc

Bóng mất trời lên cao.

A bowl of meritorious water

Flows with causality to transform the world

Brightly shining continues to light the torch

When the shadow disappears, the sun rises behind the mountains.

By implication, this Kệ (or stance) intends to evoke the 8 kings of the Lý dynasty, from the founder Lý Công Uẩn to the last king Lý Huệ Tông, through the word bát which means both bowl and eight in Vietnamese. As for Huệ Tông, his given name is Sảm. Being the combination of two words 日 nhật (sun) and 山 sơn (mountain) in Chinese Han characters, the word Sảm indeed means « the sun hides behind the mountains, » signifying the end or disappearance. This kê proves to be prophetic because Princess Lý Chiêu Hoàng (daughter of King Lý Huệ Tông) ceded the throne to her husband Trần Cảnh, who was none other than King Trần Thái Tông of the Trần dynasty. It can be said that the Lý dynasty had the kingdom by the will of God, but it was also by this will that they lost it.

Lý Bát Đế

Version française

Version vietnamienne

Galerie des photos

At a time when the kingdom of Funan was weakening, a vassal principality of this kingdom, which Chinese historians often referred to as Chenla (Chân Lạp) in their annals, attempted to forge its destiny in the middle Mekong basin near the archaeological site of Vat Phu in the Champassak province (present-day Laos). This is the only name we have to this day. No Sanskrit or Khmer word corresponds to the ancient sound Tsien lap. The existence of this kingdom dates back to the end of the 6th century. Similar to the kings of Funan, those of Chenla also have a dynastic legend: a solar-origin Brahmin priest named Kambu Svayambhuva received from the god Shiva himself a nymph of lunar origin in marriage, the beautiful Mera.

From this union of K(ambu) and Merâ, a line of sovereigns was born, that is, the descendants of Kambujadesha, meaning « land of the descendants of Kambu, » intended to explain the name of the Khmers. This word Kambujadesha, abbreviated as Kambuja, was first discovered in 817 in an inscription of Po Nagar in Champa (or present-day Nha Trang, Vietnam).

During the French colonial period, this name Kambuja was Francized as « Cambodge. » As for the word Chenla, it appeared in the history of the Sui (589-619), where the sending of an embassy from this country was mentioned in 616-617. Located southwest of Lin Yi (future Champa) and a vassal state of Funan, the kingdom of Chenla (Chân Lạp) (future Cambodia), having become powerful, did not hesitate to seize the latter and subjugate it. This fact was reported not only in the New History of the Tang (618-907) by the Chinese historian Ouyang Xiu but also in an unpublished inscription from Sambor-Prei Kuk, which praised the king of Chenla, Içanavarman I, son of King Mahendravarman, for having expanded his parents’ territory with his grand exploits. This monarch established his capital at Sambor-Prei Kuk, renamed Ishanapura.

The fragmentation of Chenla into small states was witnessed again. It was only in 654 that Jayavarman I, a great-grandson of Içanavarman I, succeeded in reunifying his ancestor’s country and established his capital near Angkor. Upon his death, Chenla again broke up into numerous principalities, and soon the principality of Shambupura (today Sambor on the Mekong) managed to impose its authority. Its king, Jayavarman II, settled in Rolûos and proclaimed himself king of the entire Kambuja in 802. Then the settlement and religious sites of the Óc Eo plain began to be abandoned as the center of gravity of the new political formation from the North moved away from the coast to gradually approach the site of the future capital of the Khmer empire, Angkor.

According to researcher J. Népote, the Khmers coming from the North through Laos appear like Germanic tribes in relation to the Roman Empire, attempting to establish a unified kingdom inland known as Chenla. They saw no interest in maintaining the technique of floating rice cultivation because they lived far from the coast. They tried to combine their own mastery of water retention with the contributions of Indian hydraulic science (the baray) to develop, through multiple trials, an irrigation system better adapted to the ecology of the hinterland and to the local varieties of irrigated rice.

It is reported that in Chinese annals, Chenla was divided into a « Land Chenla » and a « Water Chenla » at the beginning of the 8th century. The former was established in the old territories of Chenla, expanded according to its military successes, from the Dangrek range to the middle Mekong valley and westward to Burinam, now part of the Thai province of Korat, while the latter corresponded to a multitude of fiefs of former Funan and was subject to the royal authority of the island of Java (Indonesia). Then, through a stele of Sdok Kak Thom dating from 1052 and found 25 km from Sisophon, we learn that Jayavarman II was crowned king in 802 after freeing his country from the tutelage of Java, and his country regained its unity under the name Chenla.

The latter soon gave way to the birth of the Angkorian empire at the beginning of the 9th century. It first experienced its peak and glory with King Suryavarman II, whom historians have often compared to the Sun King Louis XIV of France. Of a warlike temperament, he did not hesitate to first ally with the Chams to attack the kingdom of Đại Việt under the reign of King Lý Thần Tôn in 1128, but he was repelled in the Nghệ An region. He then tried to maintain his grip on Champa by placing his brother-in-law Harideva as ruler over the capital Vijaya (present-day Bình Định in Vietnam).

But this attempt ended in a crushing failure against one of the greatest Cham kings, Jaya Harivarman I, who recaptured Vijaya in 1149. Yet Chinese chroniclers spoke of him with great deference. Beyond the frenzy of his territorial conquests, Suryavarman II had a large number of splendid monuments built, among which was the famous site of Angkor Wat. According to the Italian researcher Maria Albanese from the I.I.A.O institute, it seems possible that Suryavarman II died following a disastrous military expedition into Vietnamese territory in 1150.

Then the empire of the Khmer kings expanded under Jayavarman VII, one of the fascinating personalities in universal history. During his reign, he managed to push back the limits of his empire by annexing Champa, Lower Burma, Thailand, and Laos. Georges Coedès, former director of the French School of the Far East (EFEO), painted for us a striking portrait of this great king, that of a pharaoh who can boast of having moved so much stone (Angkor Thom, Ta-Prohm, Bantay-Kdei, etc.).

Map of the empire

But after his death, due to the gigantic enterprises and incessant wars against his neighbors (Chams, Vietnamese, and Thais), the Angkorian empire began to experience a rapid decline caused by the multiple capture and sacking of its capital Angkor by the Thais (1353, 1393, and 1431). They were unified by Ramadhipathi to found the kingdom of Ayutthaya.

Faced with the assaults of the Thais, the Khmers had to abandon their capital Angkor and retreat to the geographic heart of their country, the Four Arms of the Mekong (Phnom Penh), with the last king of the Khmer empire and the first king of Cambodia, Ponhea Yat. This strategic and economic retreat is only one of the hypotheses suggested by researchers to hasten the decline of Angkor. But according to recent discoveries reported by National Geographic in its issue 118 of July 2009, the collapse of Angkor is largely due to climatic disasters that managed to destroy the most complex and ingenious hydraulic system, a jewel of Khmer civilization. The imperial city of Angkor had to face severe successive droughts from 1362 to 1392 and from 1415 to 1440, thanks to the analysis of growth rings found in certain long-lived cypresses such as teak or Siam wood.

When the hydraulic system began to malfunction, showing signs of weakness, the power of the Angkorian empire did the same. This is why, being the first to realize the importance of this system, the archaeologist Bernard Philippe Groslier of the French School of the Far East (EFEO) did not hesitate to describe Angkor as a « hydraulic city » when publishing his work in 1979. Designed to support religious rituals and ensure a constant water supply for rice cultivation, the gigantic barays (or water reservoirs) were drained in the event of successive major droughts. This could have dealt a fatal blow to this already faltering empire, weakened by internal divisions and successive Thai invasions, as Angkor was home to no less than 750,000 inhabitants over an area of about 1000 km². This brings to mind the period experienced by the Maya cities of Mexico and Central America, which succumbed to overpopulation and environmental degradation linked to three successive droughts in the 9th century. This disaster also brutally reminds us of the limits of human ingenuity, which can be easily overcome at any time by the forces of nature. Man cannot conquer nature under any circumstances but must become one with nature to live in harmony with it.

Bibliographie.

Thierry Zéphir: L’empire des rois khmers; Découvertes Gallimard. 1997

Claude Jacques, Michael Freeman : Angkor, cité khmère. Book Guides

Bernard Philippe Groslier: Indochine. Editions Albin Michel 1961

National Geographic: Angkor . Pourquoi la grande cité médiévale du monde s’est effondrée? N° 118. Juillet 2009

Maria Albanese: Angkor. gloire et splendeur de l’empire khmer. Editions White Star

Georges Coedès: Cổ sử các quốc gia Ấn Độ Hóa ở Viễn Đông. Editions Thế Giới. 2011

Chu Đạt Quan: Chân Lạp phong thổ ký. Editions Thế Giới . 2011

Saïgon (Hồ Chí Minh city)

Saïgon hai tiếng nhớ nhung

Ra đi luyến tiếc nghìn trùng cách xa

Version vietnamienne

Version française

Galerie des photos

For some Vietnamese, the city will always be Saigon. For others, it is truly Ho Chi Minh City. Whatever name it takes, it will continue to be the economic center for foreign businessmen. It is here that millions of tons of rice and fish from the Mekong Delta are shipped for export. Although renamed in 1975, Saigon continues to maintain its old habits, its vagaries and its paradoxes. The city is always bustling with sleepless nights. It is a common sight on the streets or in large wooden-floored rooms where young girls learn to waltz and tango.

Saigon is still very much alive with its current 10 million inhabitants. Saigon has always had a strong vitality with a wonderful spirit of resourcefulness. The city is still bohemian, adventurous and over-excited. It continues to develop with luxury hotels with thousands of rooms in the middle of poor areas. This is the most populous city in Vietnam with an average population density of more than 4,500 people per square kilometer, even higher than Shanghai (China). It currently has a total area of 2,061 km² and is divided into 19 districts and 5 suburban districts.

Sites to visit

It was once, during the colonial era, the Pearl of the Far East and then the capital of South Vietnam from 1956 to 1975. Today, thanks to the urban development project of the Thủ Thiêm peninsula and the recent incorporation of Thủ Đức district, it has managed to expand its urban area and rapidly increase its population while simultaneously beginning the process of metropolitanization. However, according to Vietnamese researcher Trần Khắc Minh from the University of Quebec in Montreal, this does not prevent a growing fragmentation of the urban fabric and an intensification of inequalities, particularly in access to housing.

From the beginning of our era to the 17th century, Saigon successively belonged to the kingdom of Funan, then Chenla, Champa, and Cambodia. Its name is mentioned for the first time in a Vietnamese source in 1776, recounting the conquest of the city by the Nguyễn lords in 1672. For the Khmers (or Cambodians), Saigon is only a distortion of the name Prei Nokor (forest city) that the Khmers gave to this city. Saigon was a swampy region infested with crocodiles and unhealthy at the end of the 17th century. It was not idyllic for the first Vietnamese settlers to choose Saigon as a land of exile. For this reason, there is always a popular song that the Vietnamese know to testify to the unhealthiness of this region.

Chèo ghe sợ sấu cắn chân

Xuống sông sợ đĩa, lên rừng sợ ma.

Rowing the boat, afraid of crocodiles biting the feet

Going down the river, afraid of leeches, going up the forest, afraid of ghosts.

Despite its flaws, it continues to remain the jugular vein of Vietnam. It is the one that teaches Vietnamese people about market socialism or the Renovation policy started in 1996 to promote industrialization and modernization. It is also the one that offers them a taste of capitalism and the adventure of investing in risky capital.

Like many other cities, Saigon had a long history before being colonized, then Americanized, and finally renamed Hồ Chí Minh City during the events of 1975.

For those interested in this city, its history and its evolution, it is recommended to read the following books:

Une somptueuse pagode chinoise au cœur de Paris.

Ngôi chùa Trung Hoa độc đáo giữa lòng Paris.

Au début du 19ème siècle, un marchand d’art chinois de nom Ching Tai Loo racheta un hôtel particulier de style français classique construit en 1880 au cœur du quartier chic, non loin du parc Monceau. Pour l’amour de son pays et le lien qu’il voulait garder avec son pays d’adoption, il demanda à l’architecte Fernand Bloc de transformer ce bâtiment en une somptueuse pagode d’inspiration chinoise peinte en rouge comme la cité interdite de Pékin dans sa totalité car à cette époque le permis de construire ne lui fut pas demandé. Malgré les protestations des gens vivant aux alentours, la maison Loo continue à exister jusqu’aujourd’hui et devient un centre d’exposition collective d’art privé pour les collectionneurs avertis. Etant invité par la galerie d’art Hioco, j’ai l’occasion de le visiter ce matin. Je suis frappé non seulement par le caractère original de cette maison insolite mais aussi la présentation des objets d’art des galeries associées à cette exposition. Un grand merci à tous les exposants.

Vào đầu thế kỷ 19, một thương gia nghệ thuật người Trung Quốc tên là Ching Tai Loo đã mua lại một biệt thự theo phong cách cổ điển Pháp được xây dựng vào năm 1880 tại trung tâm khu phố sang trọng, không xa công viên Monceau. Vì tình yêu dành cho đất nước Trung Hoa và mong muốn giữ mối liên kết với quê hương thứ hai của mình, ông đã nhờ kiến trúc sư Fernand Bloc biến tòa nhà này thành một ngôi chùa lộng lẫy mang cảm hứng từ Trung Hoa, được sơn đỏ như Tử Cấm Thành ở Bắc Kinh, bởi vì vào thời điểm đó ông không cần xin giấy phép xây dựng. Mặc dù có sự phản đối từ những người sống xung quanh, ngôi nhà Loo vẫn tồn tại đến ngày nay và trở thành trung tâm triển lãm nghệ thuật tư nhân dành cho các nhà sưu tập tinh tường. Được mời bởi phòng tranh Hioco, tôi đã có cơ hội tham quan nơi nầy vào sáng nay. Tôi không chỉ có ấn tượng bởi tính độc đáo của ngôi nhà kỳ lạ này mà còn bởi cách trưng bày các tác phẩm nghệ thuật của các phòng tranh liên kết với cuộc triển lãm nầy. Xin gửi một lời cảm ơn chân thành đến tất cả các nhà triển lãm.

At the beginning of the 19th century, a Chinese art dealer named Ching Tai Loo bought a French classical-style townhouse built in 1880 in the heart of the upscale district, not far from Parc Monceau. For the love of his country and the connection he wanted to maintain with his adopted country, he asked architect Fernand Bloc to transform this building into a sumptuous pagoda inspired by Chinese design, painted red like the Forbidden City of Beijing in its entirety, as at that time no building permit was required. Despite protests from the local residents, the Loo house continues to exist today and has become a private collective art exhibition center for discerning collectors. Invited by the Hioco art gallery, I had the opportunity to visit it this morning. I was struck not only by the original character of this unusual house but also by the presentation of the art objects from the galleries associated with this exhibition. A big thank you to all the exhibitors.

Thành phố Menton (Côte d’Azur)

Version française

Version anglaise

Galerie des photos

Được gọi là ngọc trai của nước Pháp, Menton là một thành phố nằm trên bờ biển Địa Trung Hải ở phía đông nam nước Pháp. Nơi đây nổi tiếng với những bãi biển tuyệt đẹp. Nằm trên sườn đồi, khu phố cổ thời trung cổ của thành phố là nơi tọa lạc của vương cung thánh đường Michel-Archange với tháp chuông có từ thế kỷ 18 và nhà nguyện trắng Penitents với mặt tiền được trang trí lộng lẫy. Nhờ di sản kiến trúc và thực vật, điều này mang lại cho Menton nhãn hiệu « Thành phố nghệ thuật và lịch sử » vào năm 1991.

Étant connue comme la perle de la France, Menton est une ville située sur la rive méditerranéenne (Côte d’Azur), dans le sud-est de la France. Elle est réputée pour ses plages. Située sur les pentes de la colline, sa vieille ville médiévale abrite la basilique Saint-Michel Archange avec son clocher du XVIIIème siècle, et la chapelle des Pénitents blancs à la façade superbement décorée. Grâce à son patrimoine architectural et botanique, cela lui donne le label « Ville d’Art et d’Histoire » en 1991.

Known as the pearl of France, Menton is a town located on the Mediterranean coast (French Riviera), in the southeast of France. It is renowned for its beaches. Situated on the slopes of the hill, its medieval old town houses the Basilica of Saint Michael the Archangel with its 18th-century bell tower, and the Chapel of the White Penitents with its beautifully decorated facade. Thanks to its architectural and botanical heritage, it was awarded the label « City of Art and History » in 1991.

Ngô Quyền

Faced with the Chinese army, which is accustomed to resorting to force and brutality during its conquest and domination of other countries, the Vietnamese must find the ingenuity to emphasize flexible and inventive tactics adapted essentially to the battlefield in order to reduce its momentum and its material superiority in men and numbers. One must never throw oneself headlong into this confrontation, as in this case one seeks to oppose the hardness of egg to that of stone (lấy trứng chọi đá) but one must fight the long with the short, such is the military art employed by the talented generalissimo Ngô Quyền. This is why he had to choose the place of the confrontation at the mouth of the Bạch Đằng River, anticipating the intention of the Southern Han to want to use it with their war fleet led by Crown Prince Liu Hung-Ts’ao (Hoằng Thao) ordered by his father Liu Kung (Lưu Cung) as King of Jiaozhi to quickly facilitate the landing in Vietnamese territory.

This celestial fleet entered the river mouth as planned. Ngô Quyền had pointed iron-covered stakes planted in the riverbed and invisible during high water prior to this confrontation. He tried to lure the celestial fleet beyond these iron-covered pointed stakes by incessantly harassing them with flat-bottomed boats. At low tide, the Chinese ships retreated in disarray in the face of attacks from Vietnamese troops, and were besieged on all sides and now hindered by the barrage of emergent piles, resulting not only in the annihilation of Chinese ships and troops, but also the death of Hung-Ts’ao.

Bạch Đằng river

Ngô Quyền was a fine strategist as he managed to perfectly synchronize the movement of the tides and the appearance of the celestial fleet in a time frame requiring both great precision and knowledge of the place. He knew how to turn the superiority of the opposing force to his advantage, for the army of the Southern Han was known to be excellent in maritime matters, and always made water or the river Bạch Đằng its ally in the fight against its adversaries. Water is the vital principle for the Vietnamese flooded rice civilization, but it is also the lethal principle, as it can become an incomparable force in their battles. As a high-ranking Chinese mandarin, Bao Chi, later noted in a confidential report to the Song emperor: the Vietnamese are a race well-suited to fighting on water.

If the Vietnamese fled to the sea, how could Song’s soldiers fight them, as the latter were afraid of the wind and the wave (1). Ngô Quyền knew how to refer to the three key factors: Thiên Thời, Địa Lợi, Nhân Hòa (being aware of weather and propitious conditions, knowing the terrain well and having popular support or national concord) to bring victory to his people and to mark a major turning point in Vietnam’s history. This marked the end of Chinese domination for almost 1,000 years, but not the last, as Vietnam continued to be a major obstacle to Chinese expansion to the south. The leading figure of Vietnamese nationalism in the early 20th century Phan Bội Châu regarded him as the first liberator of the Vietnamese nation (Tổ trùng hưng).

How could he succeed in freeing his people from the Chinese yoke when we knew that at that time our population was about a million inhabitants facing a Chinese behemoth estimated at more than 56 million inhabitants. He must have had courage, inventive spirit and charisma to succeed in freeing himself from this yoke with his supporters. But who is this man that the Vietnamese still consider today as the first in the list of Vietnamese heroes?

Đường Lâm village

Ngo Quyen was born in 897 in Đường Lâm village, located 4 kilometers west of the provincial town of Sơn Tây. He was the son of a local administrator, Ngo Man. When he was young, he had the opportunity to show his character and his willingness to serve the country. In 920, he served Dương Đình Nghệ, a general from the family of Governor Khúc of Ái Châu (Thanh Hóa) province. Dương Đình Nghệ had the merit of defeating the Southern Han by taking the capital Đại La (formerly Hànội) from them in 931 and now declared himself governor of Jiaozhi. He entrusted Ngo Quyen with the task of administering the Ái Châu province. Finding in him great talent and determination to serve the country, he decided to grant him the hand of his daughter. During his 7 years of governance (931-938), he proved to bring peaceful life to this region.

In 937, his father-in-law Dương Đình Nghệ was assassinated by his subordinate Kiều Công Tiễn to take the post of governor of Jiaozhi. This heinous act provoked the anger of all sections of the population. Ngô Quyền decided to eliminate him in the name of his in-laws and the nation because Kiều Công Tiễn asked for help from the Southern Han emperor, Liu Kung. For the latter it was a golden opportunity to reconquer Jiaozhi.

Unfortunately for Liu Kung, this risky military operation ended a long Chinese domination in Vietnam and allowed Ngô Quyền to found the first feudal dynasty in Vietnam. In 939, he proclaimed himself king of Annam and established the capital at Cổ Loa (Phúc Yên). His reign lasted only 5 years. He died in 944. His brother-in-law Dương Tam Kha took advantage of his death to seize power, which provoked the anger of the entire population and led to the breakup of the country with the appearance of 12 local warlords (Thập nhị sứ quân).This political chaos lasted until the year 968 when a brave boy from Ninh Binh, Dinh Boy Linh, succeeded in eliminating them one by one and unifying the country under his banner. He founded the Dinh Dynasty and was known as « Dinh Tien Hoang ». He settled in Hoa Lu in the Red River region and Vietnam at that time was known as « Dai Co Việt (Great Việt) ».

Bibliography

Hoàng Xuân Hãn: Lý Thường Kiệt, Univisersité bouddhique de Vạn Hạnh Saigon 1966 p. 257

Lê Đình Thông: Stratégie et science du combat sur l’eau au Vietnam avant l’arrivée des Français. Institut de stratégie comparée.

Boudarel Georges. Essai sur la pensée militaire vietnamienne. In: L’Homme et la société, N. 7, 1968. numéro spécial. 150° anniversaire de la mort de Karl Marx. pp. 183-199.

Trần Trọng Kim: Việtnam sử lược, Hànội, Imprimerie Vĩnh Thanh 1928