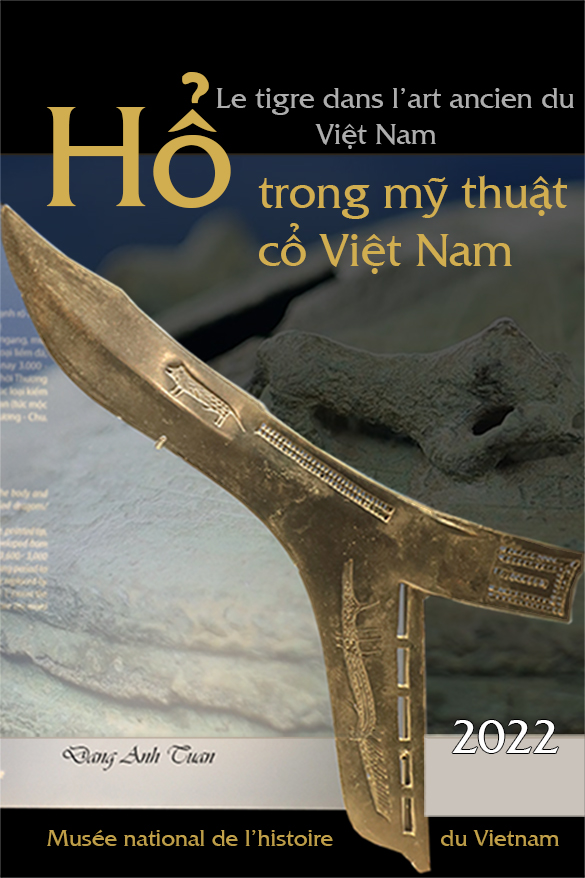

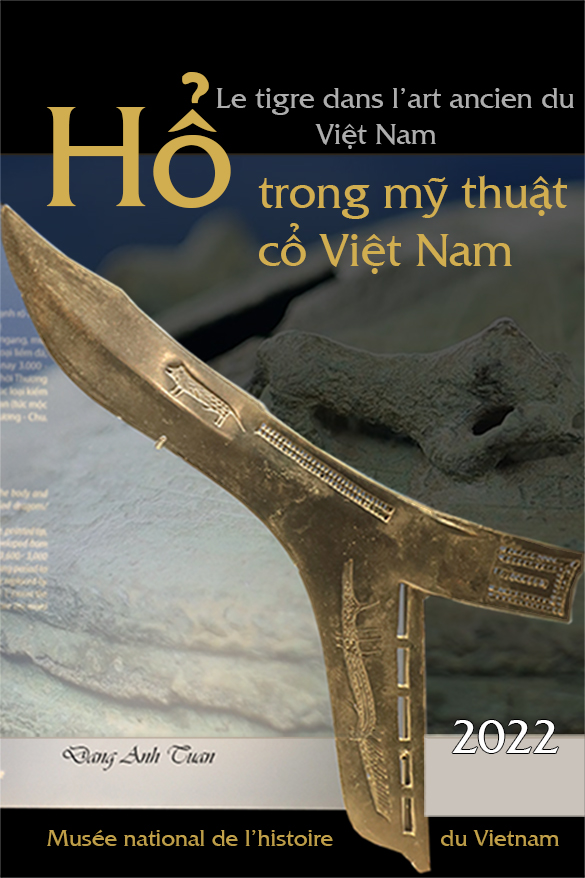

Hổ trong mỹ thuật cổ Việt Nam

The tiger in ancient Vietnamese art

Version française

English version

Đối với đại đa số người Việt, hổ là một con vật đáng kính sợ. Vì sợ hổ trả thù nên họ dành cho hổ những dấu hiệu tôn thờ qua những ngôi miếu dành riêng cho hổ hay thường thấy được nằm rải rác ở khắp khu rừng sâu thẩm ở miền núi. Đến nay còn thấy nhiều dân tộc ở miền núi còn thờ hổ. Có thể có liên quan đến tín ngưỡng vạn vật hữu linh của cư dân thưở xưa. Ngoài sức manh uy phong lẫm liệt của hổ, nó còn thường được xem là con vật có khả năng nghe lén các cuộc đàm thoại của họ. Vì vậy hổ được gọi là ông thính. Để tránh gọi tên hổ, người dân Việt hay thường ám chỉ hổ với cái tên là « ông ba mươi ».

Ngay cả trước khi giết hổ sau khi bắt được nó, họ cũng không quên bày tỏ lòng tôn kính lần cuối bằng cách tổ chức một buổi nghi lễ trước đó. Họ thường so sánh họ với hổ qua câu châm ngôn như sau:

Hùm chết để da, người chết để tiếng.

Rất tiếc ngày nay hổ ở Đông Dương không còn nhiều nữa và đang ở trong tình trạng nguy cơ tuyệt chủng vì các bộ phận của hổ được dùng làm thuốc đông y, được bán với giá cao trên thị trường chợ đen, giá 100 gram cao hổ cốt bán tới 1.000 đôla.

Sự xuất hiện hình ảnh hổ trong nghệ thuật cổ được thấy từ thời kỳ Đồng Sơn qua các chuôi dao gâm thường được kết hợp với voi hay rắn được thấy ở di chỉ Làng Vạc ở Nghệ An chẵng hạn hay các thạp đồng như thạp VạnThắng (Cẩm Xuyên, Phú Thọ). Thạp nầy được trưng bày ở bảo tàng lịch sử quốc gia với bốn tượng hổ cập mồi rất sinh động quay vòng trên nấp thạp hay chiếc qua đồng có hình hổ được khắc hai mặt với những chấm trên thân được nhà khảo cứu Pháp Louis Pajot sưu tầm và đưa về trưng bày ở bảo tàng Finot (nay là bảo tàng lịch sử quốc gia ở Hànội). Ngoài ra còn có các hình hổ trang trí bằng họa tiết chìm. Điều nầy thể hiện được nghệ thuật điêu khắc và trang trí của người Đồng Sơn mang tính tả thực và ước lệ. So với các hình ảnh rồng, phượng, hưu, cá, vịt vân vân thì hình ảnh hổ rất hiếm hoi trên đồ gốm. Tuy nhiên thạp gốm hoa nâu nổi tiếng nhất là thạp hoa nâu khắc hình ba con hổ đuổi nhau được thấy ở bảo tàng Guimet (Paris).

Những hình hổ được thấy ngày nay không còn mang ý nghĩa tâm linh, tín ngưỡng hay sợ hải nữa mà chỉ dùng để thể hiện sự phong phú đa dạng trong việc trang trí trên các đồ gốm hay tạo ra bằng đá nhầm để lại một dấu ấn riêng biệt theo sở thích của người đặt mua hàng.

Version française

Pour la grande majorité des Vietnamiens, le tigre est un animal redoutable. Par peur de vengeance, ils donnent aux tigres des signes d’adoration à travers des temples dédiés aux tigres, souvent dispersés dans la forêt profonde des montagnes. Jusqu’à présent, de nombreux groupes ethniques des régions montagneuses vénèrent encore les tigres. Cela peut être lié aux croyances animistes des anciens habitants. Outre la force imposante et majestueuse du tigre, il est aussi souvent considéré comme un animal capable d’écouter leurs conversations, ce qui fait de lui connu sous le nom « Monsieur l’écouteur (Ông thính) ». Pour éviter de l’appeler sous son propre nom « Hổ ou cọp), les Vietnamiens se réfèrent aux tigres avec le nom « Monsieur Trente ». Avant même de le tuer après l’avoir attrapé, ils n’ont pas oublié de lui rendre un dernier hommage en lui organisant au préalable un rituel. Ils se comparent souvent aux tigres à travers le proverbe suivant:

Le tigre mort laisse sa peau et l’homme décédé sa réputation.

Malheureusement, il n’y a pas beaucoup de tigres en Indochine aujourd’hui. Ces derniers sont en voie d’extinction car toutes les organes de leur corps sont utilisés dans la médecine traditionnelle chinoise et sont vendues à prix d’or sur le marché noir. C’est le cas de la poudre issue d’os de tigre et proposée avec un prix élevé de 100 grammes à 1 000 dollars.

On voit apparaître les images des tigres souvent associées à des éléphants ou des serpents dans l’art ancien à l’époque de Đồng Sơn, sur les lames des poignards trouvés sur le site de Làng Vạc à Nghệ An par exemple, ou bien des situles en bronze comme la situle Vạn Thắng. (Cẩm Xuyên, Phú Thọ). Cette dernière est exposée au musée national de l’histoire avec quatre blocs de statues de tigres capturant la proie et répartis de manière circulaire sur le couvercle de la situle ou la hache en bronze (qua đồng) recueillie par le chercheur français Louis Pajot qui a eu le mérite de l’offrir au musée Finot (*). On trouve l’image d’un tigre gravée sur les deux faces de la hache avec des points. Il existe également des images de tigre décorées de motifs en creux. Cela montre que l’art de la sculpture et de la décoration du peuple dôngsonien est réaliste et conventionnel. Comparées aux figures de dragons, de phénix, de cerfs, de poissons, de canards etc., celles des tigres sont très rares sur la céramique. Pourtant le vase à glaçure brune le plus célèbre est celui de trois tigres dans la poursuite, trouvé au musée Guimet (Paris). Les images des tigres vues aujourd’hui ne reflètent plus le caractère spirituel, religieux ou de peur. Elles sont utilisées uniquement dans le but de montrer la richesse et la diversité de la décoration dans la céramique ou dans la pierre et de laisser ainsi une marque particulière selon le goût et les préférences de l’acheteur.

(*) C’est le musée national de l’histoire de Hanoï.

English version

For the vast majority of Vietnamese people, the tiger is a formidable animal. Out of fear of revenge, they show signs of worship to tigers through temples dedicated to tigers, often scattered deep in the mountain forests. To this day, many ethnic groups in mountainous regions still venerate tigers. This may be related to the animist beliefs of the ancient inhabitants. Besides the imposing and majestic strength of the tiger, it is also often considered an animal capable of listening to their conversations, which is why it is known as « Mr. Listener (Ông thính). » To avoid calling it by its own name « Hổ or cọp, » the Vietnamese refer to tigers as « Mr. Thirty. » Even before killing it after catching it, they do not forget to pay it a last tribute by organizing a ritual in advance. They often compare themselves to tigers through the following proverb:

The dead tiger leaves its skin and the deceased man his reputation.

Unfortunately, there are not many tigers in Indochina today. They are endangered because all the organs of their bodies are used in traditional Chinese medicine and are sold at exorbitant prices on the black market. This is the case with powder made from tiger bones, which is offered at a high price of $1,000 per 100 grams.

Images of tigers often appear alongside elephants or snakes in ancient art from the Đông Sơn period, such as on the blades of daggers found at the Làng Vạc site in Nghệ An, or on bronze situlas like the Vạn Thắng situla (Cẩm Xuyên, Phú Thọ). The latter is exhibited at the National History Museum along with four blocks of tiger statues capturing prey, arranged in a circular manner on the lid of the situla, or the bronze axe (qua đồng) collected by the French researcher Louis Pajot, who had the merit of donating it to the Finot Museum (*). The image of a tiger is engraved on both sides of the axe with dots. There are also images of tigers decorated with incised patterns.This shows that the art of sculpture and decoration of the Đông Sơn people is realistic and conventional. Compared to figures of dragons, phoenixes, deer, fish, ducks, etc., those of tigers are very rare on ceramics. However, the most famous brown-glazed vase is the one with three tigers in pursuit, found at the Guimet Museum (Paris). The images of tigers seen today no longer reflect spiritual, religious, or fearsome characteristics. They are used solely to showcase the richness and diversity of decoration in ceramics or stone and thus leave a particular mark according to the taste and preferences of the buyer.

(*) This is the National Museum of History in Hanoi.

[Return RELIGION]