Han Dynasty

Han Dynasty

for four centuries (From 206 BC -220 AD)

Version française

Version vietnamienne

The Chinese are proud to be the sons of the Han. They feel better treated under the Han dynasty because it managed to give them relative freedom and practiced a policy of appeasement and cultural unification, which was missing after years of blind absolutism, wars, and atrocities under the first short-lived Qin dynasty from 221 to 206 BC. This dynasty was founded by Zheng Ying, the ruler of a peripheral kingdom in the northwest of China, descended from the non-Chinese Rong tribe from the steppes. Yet, thanks to the administrative and legislative reforms successively undertaken by the legalists Shang Yang (Thương Ưởng), Han Fei (Hàn Phi), and Li Si (Lý Tư), the latter known as Shi Huang Di, he succeeded in giving them a centralized and unified empire after fierce struggles against the six rival states (Warring States Period) (Chiến Quốc), not to mention the annexation of the Ba and Shu kingdoms in the Sichuan province (Tứ Xuyên) in 316 BC. To prevent any signs of resistance and local particularities, he adopted the policy of population transfer to the north and northwest. More than 100,000 wealthy and influential people belonging to the former states of Chu (Sỡ Quốc) and Qi (Tề Quốc) were relocated in 198 BC to the capital.

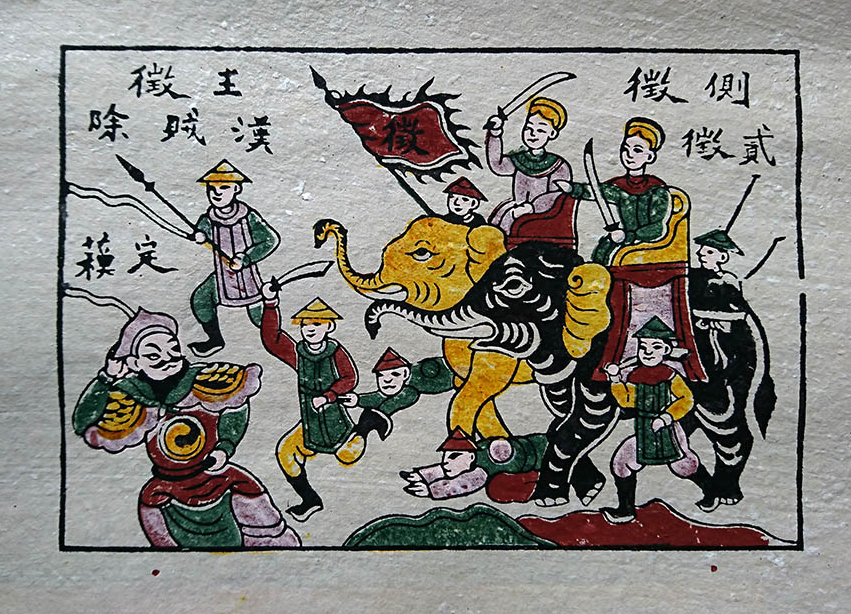

To expand his empire, he soon launched military expeditions not only to the North against the Xiongnu (Hung Nô) but also to the south in Fujian (Phúc Kiến), Guangdong (Quảng Đông), Guangxi (Quảng Tây), and Northern Vietnam (Giao Chỉ). It was in these southern regions that, after his death, one of his generals named Zhao To (or Triệu Đà), allied with the Yue, founded the kingdom of Nan Yue (or Nam Việt), which Vietnamese historians still consider their territory because it succeeded in annexing in the meantime the Âu Lạc kingdom of the Vietnamese. Eliminating several rival generals and emerging victorious from the final confrontation with the brilliant descendant of the general Xiang Yang (Hạng Yên) of Chu, Xiang Yu (Hạng Vũ), the former uneducated relay leader turned bandit chief Liu Bang (Lưu Bang), who came from the common class, proclaimed himself emperor in 202, established his capital at Chang’an (not far from present-day Xi’an), and thus founded the Han dynasty. He will go down in history under the name Gaozu (Hán Cao Tổ). His rise was due neither to birth nor family but rather to his talent in managing the abilities of his three companions, each having a decisive role in the conquest of power: governance with Xiao He (Tiêu Hà), strategy with Zhang Liang (Trương Lương), and military tactics with Han Xin (Hàn Tín).

According to the French historian René Grousset, Liu Bang was the beneficiary of the work accomplished by the genius Qin Shi Huang Di, who had created from scratch the imperial centralization and Chinese unity. During sixty years of reign, Gao Zu’s successors had to face problems of intrigue and insubordination due to their laissez-faire and appeasement policies, raised by the empire’s nobility, as well as frequent invasions by the Xiongnu coming from Central Mongolia. These were probably the Protomongols or Proto-Turks. They constituted a formidable threat to the Han dynasty since they were unified under the command of Mao Dun (Mặc Đốn) (209-174 BC). They would later do the same in Europe with Attila.

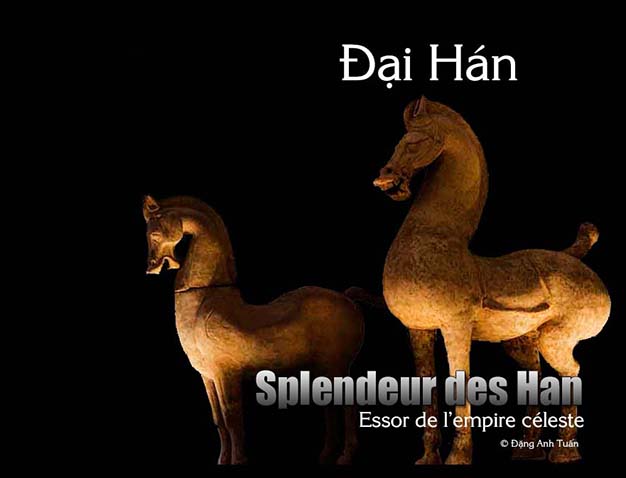

Hostilities between the Han and the Xiongnu took place in 201 when the latter invaded Shanxi. Gaozu nearly got captured on the Baideng plateau near Pingcheng in northern Shanxi. He owed his salvation only to cunning by having Mao Dun hold the portrait of a Chinese beauty. During this confrontation, he realized that his cavalry remained the Achilles’ heel of his army, which was largely composed of infantry. This was not the case for the Xiongnu (Hung nô) with the astonishing mobility of their cavalry. They were accustomed from a young age to riding sheep and shooting birds with bow and arrows.

They were skilled in handling a bow and serving in the cavalry during wartime. Moreover, these individuals, regardless of their qualities as horsemen, had the small Mongolian horse whose endurance was well established. Gaozu understood the necessity of equipping his army with an equivalent force. Since the number of stud farms remained very limited at that time in the commanderies, his successor, Emperor Wendy, had to resort to a decree stipulating that each family sending a horse to the state would be exempt from conscription for three of its members.

Furthermore, in the Han army, there was no difference between riding horses and draft horses because they belonged to the same breed. Chinese steeds were recognized by their massive bodies, short legs, and broad necks, and they were much less resilient. To consolidate power within his empire and to buy time in strengthening his cavalry, Gaozu was forced to sign a friendship pact known as heqin in 198 with the shanyu Modu (or Maodun). He had to send him an annual tribute consisting of a fixed quantity of silks, liquors, rice, and foodstuffs in exchange for the cessation of hostilities. Additionally, a princess from the royal family was given in marriage to the shanyu (emperor of the Xiongnu).

It is a way for China to buy peace at a high price in the hope of not being attacked by the Xiongnu and to sinicize the barbarians because their emperor thus became the son-in-law of the Han court. Chinese poetry is not lacking in sneers and complaints, comparing the princess to a « Chinese partridge » given in marriage to the « wild bird of the North. » There is Chinese contempt in the designation of these barbarians by the word « Xiongnu, » which means « fierce slave. » The most famous case remains that of the concubine Wang Zhao Jun (Vương Chiêu Quân) during the reign of Emperor Yuandi (Hán nguyên Đế).

This reminds us of the same approach later used by the Vietnamese king Trần Nhân Tôn with Princess Huyền Trân Công Chúa to ally with Champa’s Jaya Sinhavarman III (Chế Mân) in the struggle against Kublai Khan’s Mongols and with the aim of obtaining in exchange the two territories of Châu Ô and Châu Rí. There is also irony about her fate, comparing her to a cinnamon tree growing in the middle of the forest and letting itself be climbed by a « Yao » or a « Mường. »

Beyond the heavy tribute, the Great Wall of China remains an essential barrier to mark the boundary between two worlds: the barbarian and the civilized, the steppe and culture. This tribute policy, which the Chinese called « gifts, » was not very profitable for the Han court but it showed how weak it was compared to the nomads because it always had to be on the defensive. Sometimes their provocation was unbearable and humiliating when the insatiable Modu set his mind on nothing less than marrying the Dowager Empress Lü Hu, the main wife of Emperor Gaozu, through his letter. However, under Chinese influence, the Xiongnu began to develop a taste for luxury in their way of dressing in silk imported from China, stylizing plaques, belt buckles in bronze or gold in their animal art similar to that of the Scythians, building fortified cities while preserving their traditional yurts, etc.

From the reign of Wendi, the Chinese contribution, to which monetary payments must be added, was always increasing significantly. Despite this, the insatiable Xiongnu continued to sporadically launch new raids. They soon had to face a worthy rival Chinese emperor. Wudi (Martial Emperor) is his reign name.

Nothing was initially planned for him to ascend to the highest position of the empire, but thanks to palace intrigues, he was enthroned at the age of 15 upon the death of his father, Emperor Jindi, in 141 BC.

Hán Vũ Đế

Emperor Wu Di (Hán Vũ Đế)

According to legend, when he was still young, he was tested by Emperor Jindi to determine if he was intelligent or not. His answer pleased him so much that Jindi undertook to educate him and changed his name to Che: the intelligent. At the beginning of his reign, he faced some difficulties with his reforms due to the laxity of his predecessors, advocated by the Daodejing (Đạo Đức Kinh), and the oversight of his relatives, particularly that of his mother Wang (who died in 126 BC) and his grandmother, the great Empress Dowager Dou (Đậu Thái hậu), supported by the court nobility. This nobility was mainly composed of supporters of huanglao (a movement favoring individual fulfillment and legalism in government) and Taoists. Her death in 135 BC allowed him to better consolidate his power and take the reins of government upon the death of his maternal uncle and prime minister Tian Fen (Điền Phần) in 131 BC. From then on, the slightest criticism of his policy was considered a crime of lèse-majesté. He thus became the absolute monarch of the empire.

This did not prevent him from listening to his advisers while respecting laws, rites, and customs. He called upon new men, scholars (or boshis), among whom was a scholar named Dong Zhongshu (Đổng Trọng Thư), a specialist in the Chronicle of Spring and Autumn (Chunqiu). On his advice, Wudi adopted Confucianism adapted to his time with various contributions, particularly borrowings from Legalism and the theory of Yin and Yang and the Five Elements. This was reflected in practice by a new, more coherent doctrine encompassing politics, the individual, and society. The rites were celebrated according to the prescriptions of the texts.

Morality, righteousness (yi), and perfect knowledge of the Classics were criteria for selecting officials in the administration through an examination. In 124 BC, Wudi founded near Chang An the great university (taixue), a kind of imperial academy dedicated to the study of Confucius’s texts. Confucianism began to spread to all layers of society. In 104 BC, Wudi abandoned the Qin calendar in favor of a calendar that took into account the first day of the first lunar month of spring instead of the first day of the tenth lunar month, often in February of the year. This is the calendar that the Chinese continue to use to this day. This did not prevent him from listening to his advisors while respecting laws, rites, and customs. He called upon new men, scholars (or boshis), among whom was the scholar Dong Zhongshu (Đổng Trọng Thư), a specialist in the Spring and Autumn Annals (Chunqiu). On the advice of the latter, Wudi adopted Confucianism adapted to his time with various contributions, particularly borrowings from Legalism and the theory of Yin and Yang and the Five Elements. This was reflected in practice by a new, more coherent doctrine that included politics, the individual, and society. The rites were celebrated in accordance with the prescriptions of the texts.

Morality, righteousness (yi), and perfect knowledge of the Classics were criteria for selecting officials in the administration through an examination. In 124 BC, Wudi founded near Chang An the great university (taixue), a kind of imperial academy dedicated to the study of Confucius’ texts. Confucianism began to permeate all layers of society. In 104 BC, Wudi abandoned the Qin calendar in favor of a calendar that took into account the first day of the first lunar month of spring instead of the first day of the tenth lunar month, often in February of the year. This is the calendar that the Chinese continue to use to this day.

Then, by finding the virtue of the earth from the fact that Liu Bang came from the common people, Wudi henceforth adopted the element « Earth » and chose the color yellow associated with it as the imperial color of the Han because this choice was established according to the teaching of the Five Elements (Wu Xing) (Ngũ Hành). By its color,

white (Metal) (Kim) for the Shang-Yin (Ân–Thương)

red (Fire) (Hỏa) for the Zhou (Châu)

black (Water) (Thủy) for the Qin (Tần)

yellow (Earth) (Thổ) for the Han (Hán),

each element has a particular meaning. Each dynasty established its power under the protection of this element. Wudi chose the element « Earth » to neutralize the « Water » of the Qin. Taking the example of the first emperor of China (Shi Huang Di) of the Qin dynasty, it is observed that he symbolically justified his right to rule because only water, represented by the color black, could destroy the power of the king of the Zhou who was under the sign of the fire element (red color). Similarly, the Zhou dynasty had succeeded in taking power from King Di Xin (in Vietnamese Trụ Vương or Đế Tân) of the Shang dynasty because the fire element of the Zhou dynasty could melt the metal, the protective element of the Shang dynasty. The Xia dynasty would probably be associated with the color green if its existence were confirmed. The succession of Chinese dynasties results in the following pattern corresponding to the cycle of destruction or domination in Wuxing:

Earth—> Water—> Fire —> Metal—> Wood

This new concept of the cosmic order of things now inspires the organization of China’s relations with other countries or the king’s relations with the people. Analogous to the purple North Star around which stars of different sizes revolve, Wudi’s China places itself at the center around which peoples of different importance revolve, each in its place. Being the Son of Heaven, the emperor placed at the center of his empire is the link between heaven and the people. He governs through justice and rites. His power is entrusted by Heaven. That is why when people obey him, they also comply with Heaven’s wishes. He is never accountable to the people but is judged only by Heaven through signs of good or bad omens on earth (natural disasters, earthquakes, good or bad harvests, floods, etc.). The three cardinal guides (the ruler guides the subject, the father guides the son, and the husband guides the wife) (Tam Cương) and the five permanent virtues (benevolence, righteousness, propriety, knowledge, and sincerity) (Ngũ Thường) become effective tools not only to consolidate the absolute power of the emperor but also to maintain order in feudal society.

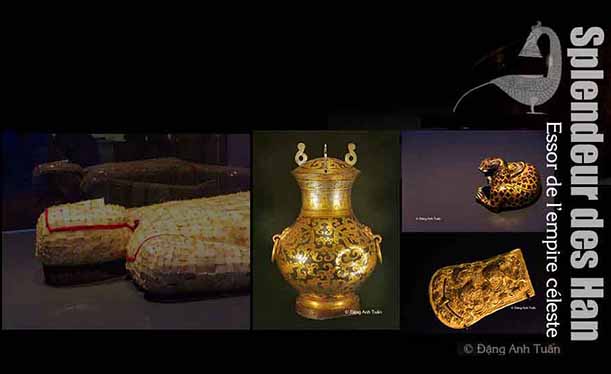

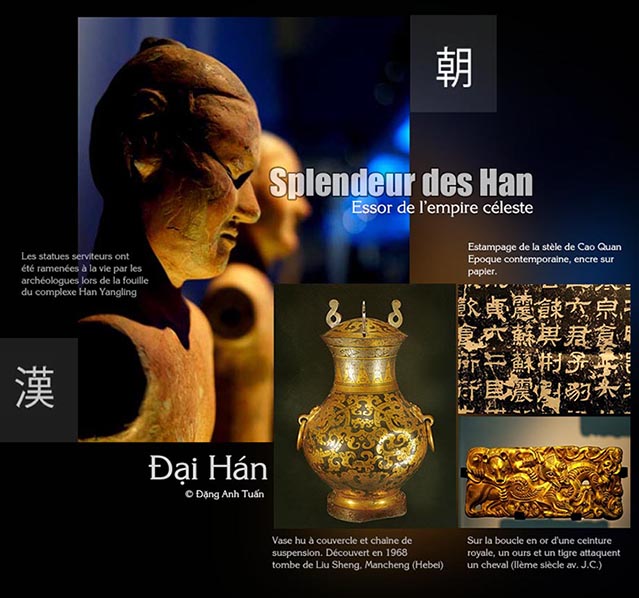

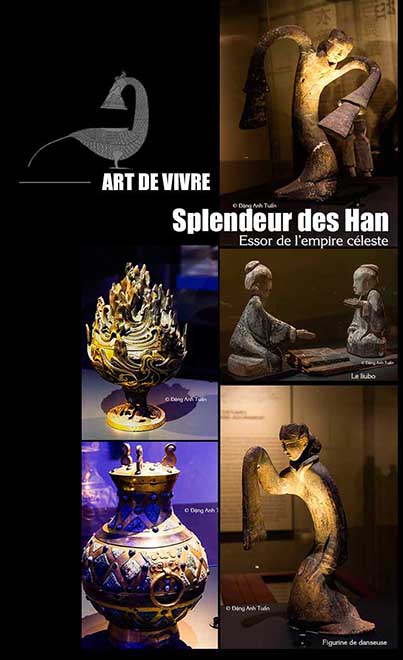

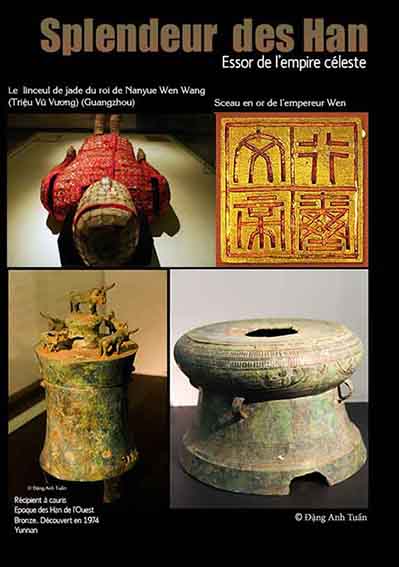

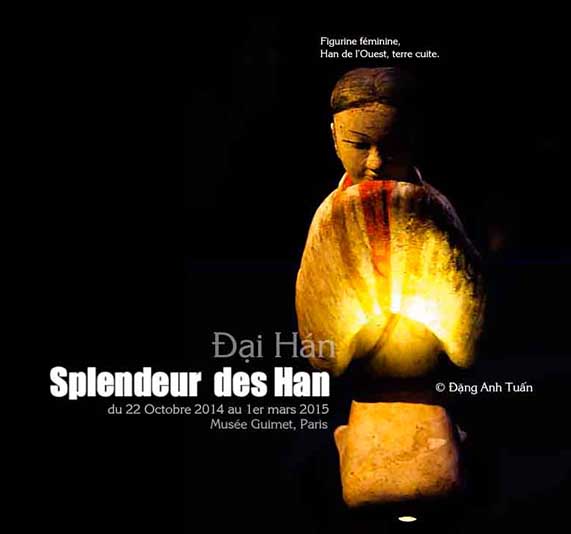

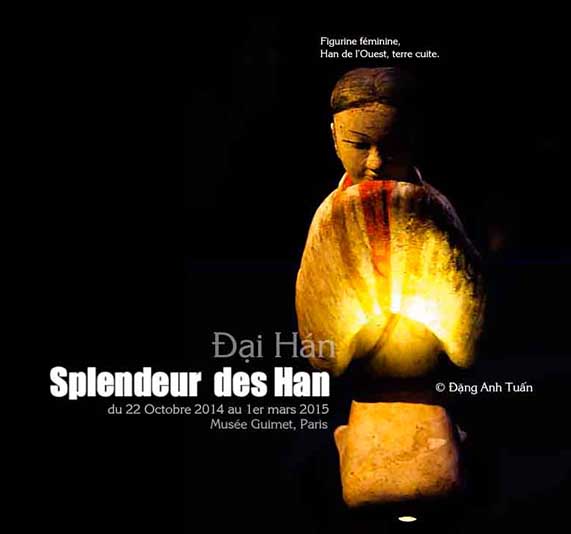

More than 200 works from 27 institutions and museums unveil Chinese society under the Han dynasty.

Guimet Museum of Asian Arts

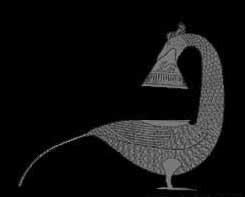

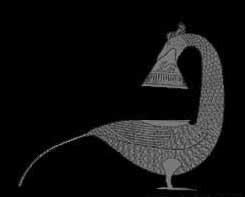

Phoenix-shaped lamp

Phoenix-shaped lamp

[Return CHINE, Empire du Milieu]