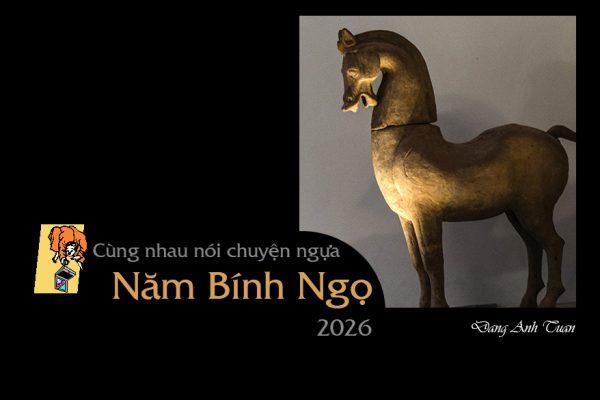

Parlons ensemble de Cheval

en cette année du Cheval de feu

Version française

Version anglaise

Galerie des photos

Ngựa là loại động vật mà không biết từ lúc nào bị loài người chinh phục được, nuôi dưởng và thuần hóa nó khiến nó trở thành từ đó một gia súc có lợi trong mọi cộng tác xê dịch, vận tải và chiến chinh. Nó là con vật không chỉ có sức mạnh phi thường, dẻo dai mà còn lại rất trung thành với chủ khiến nó đựợc xem một vũ khí lợi hại trong binh mã. Những chiến công hiển hách ở đất nước ta đều có sự tham gia của ngựa. Bởi vậy vua chúa ta hay thường tri ân ngày xưa bằng cách tạc hình ngựa voi bằng đồng bằng đá cùng các quan văn quan võ với quân sĩ để minh chứng những thời oanh liệt của dân tộc ta chống ngọai xâm. Người với ngựa như hình với bóng trong thời chinh chíến, chia sẻ gian truân cùng chung số phận. Không chỉ nữ sĩ Đoàn Thị Điểm đã nhắc lại sự việc nầy trong « Chinh Phụ Ngâm»:

Hơi gió lạnh người rầu mặt dạn

Dòng nước sâu ngựa nản chân bon

Ôm yên gối trống đã chồn

Nằm vùng cát trắng, ngủ cồn rêu xanh

Còn Thái Thượng Hoàng Trần Thánh Tông bùi ngùi khi trở về kinh thành sau chiến thắng giặc Nguyên Mông và thấy những con ngựa đá, chân còn dính bùn ở trước ngọ môn, phải thốt lên trong lễ hiến phu hai câu thơ như sau:

Xã tắc hai phen bon ngựa đá

Non sông thiên cổ vững âu vàng.

Trong truyền thuyết nước ta có hai lần nhắc đến con ngựa. Lần đầu ở trong truyền thánh Gióng tức là Phù Đổng Thiên Vương. Dưới thời ngự trị của vua Hùng Vương thứ VI thì có giặc Ân-Thương ở bên Tàu rất hùng mạnh xâm chiếm nước ta. Vua buộc lòng sai người đi rao khắp nơi để kiếm người tài năng ra giúp nước diệt giặc. Lúc bấy giờ ở làng Phù Đổng tỉnh Bắc Ninh có một đứa trẻ còn nằm nôi, nghe sứ giả đi mộ khắp dân gian xem có ai phá được giặc thì ban cho tước lộc. Bé dậy hỏi mẹ, mẹ mới bảo rõ ràng như vậy. Thánh Gióng mới nói: « Thế thì mẹ đem nhiều cơm đến đây cho con ăn » theo lời kể trong Việt Điện U Linh. Ngài mới ăn vài chén cơm.

Mấy tháng sau ngài cao lớn lên, rồi tự ra ứng mộ. Sứ giả thấy lạ mới đem ngài về kinh sư. Theo lời thỉnh cầu của ngài, vua mới cho người đúc một con ngựa sắt và một chiếc roi dài cũng bằng sắt. Sau khi ăn mấy nong cơm mới thổi xong, ngài mới vươn vai một cái thì ngài cao lớn hơn 10 thước rồi ngài nhảy lên lưng ngựa, cầm côn sắt mà hét lớn « Ta là thiên tướng đấy » rồi phi thẳng ra chiến trường. Ở nơi nầy, ngài thì hoa côn, ngựa thì phun lửa, giết vô số quân địch khiến nỗi làm côn gãy và buộc lòng nhổ tre mà đánh tiếp khiến quân Ân tẩu tán khắp nơi. Sau đó ngài phóng ngựa lên núi Sốc Sơn rồi biến mất. Vua Hùng nhớ ơn mới truyền lập đền thờ ở làng Phù Đổng thuộc huyện Gia Lâm ngoài thành Hà Nội. Năm nào cũng có lễ hội để tưởng nhớ ngài cả vào ngày mùng 8 tháng 4.

Chúng ta nên nhớ lại nước ta rất rộng lớn lúc bấy giờ tên là Văn Lang được giáp tới Nam Hải (Quảng Đông) ở phiá đông, phía tây với Ba Thục (hay Tứ Xuyên), ở phía bắc thì tới Ðộng Ðình hồ (Hồ Nam) và phía nam với vương quốc Hồ Tôn tức là Chiêm Thành (Chămpa). Dân tộc ta là nhóm dân Bách Việt còn sống thời đó ở vùng sông Dương Tử bên Tàu.

Trong Kinh Dịch được dịch bởi giáo sư Bùi Văn Nguyên thì tác giả có nói đến một cuộc viễn chinh quân sự được thực hiện trong vòng ba năm bởi vua hiếu chiến của nhà Ân-Thương tên là Vũ Định (Wu Ding) ở vùng Ðộng Ðình Hồ (Kinh Châu) chống lại các dân du mục, thường được gọi là « Qủi ». Dù biết là truyền thuyết nhưng với các cuộc khai quật gần đây, các cuộc thí nghiệm ADN, thì truyền thuyết nầy không phải chuyện hoang đường mà nó nói lên có sự xung đột giữa dân tộc ta với nhà Ân. Bởi vậy nước Văn Lang không có thiết lập bất kỳ mối quan hệ thương mại nào ở thời đó với nhà Ân-Thương cả.

Lần thứ nhì, ngựa được nhắc đến trong truyên Sơn Tinh Thủy Tinh. Trong truyền thuyết nầy, vua Hùng vương thứ 18 có một người con gái là Mị Nương, sắc đẹp lạ thường. Khi đến tuổi lấy chồng, tiếng tăm của nàng lại càng vang lên ở khắp bốn phương. Nhà vua quyết định chọn cho nàng một người chồng tài giỏi. Lúc đó có hai chàng trai, thông minh và tuấn tú, tình cờ đến cùng một lúc và xin cầu hôn Mị Nương. Một người được gọi là Sơn Tinh, chúa của các vùng núi non cao và các rừng sâu, còn người kia là Thủy Tinh, chúa các của các sông nòi và biển cả thăm thẳm.

Băn khoăn, vua cha không biết phải chọn người nào vì cả hai đều có tài năng vô song và quyền lực vô hạn nên mới bày ra thữ thách như sau: một trăm đĩa xôi, một con voi chín ngà, một con gà trống chín cựa, một con ngựa chín hồng mao. Người nào đem đến trước với sính lễ nầy được làm chồng của Mị Nương.

Ngày hôm sau, lúc rạng đông, Sơn Tinh đến trước với đầy đủ lễ vật và đưa người đẹp lên núi. Vừa hoang mang vừa tức giận, Thủy Tinh lao tới, dâng cao lên mực nước, quyết định vào núi bắt cóc Mị Nương. Sơn Tinh nâng núi cao hơn nữa. Thủy Tinh trổ tài năng của mình, đánh đuổi gió bão, sấm chớp làm rung chuyển cả núi rừng. Sơn Tinh giữ núi một cách vững vàng. Thủy Tinh nhờ đến thủy binh mà xông lên theo dòng nước, xông pha toàn lực. Sơn Tinh dùng các lưới sắt, cắt đường tiếp tế, lăn đá lấp hồn và đè bẹp các thủy quái trôi dạt vào bờ. Chuyện nầy được kể lại trong Lĩnh Nam Chích Quái của Trần Thế Pháp dưới tên là Truyện núi Tản Viên. Cứ hàng năm cở tháng bảy tháng tám dân ở vùng chân núi nầy hay thường bị gió to nước lớn làm ruộng đồng bị thiệt hại.

Trong sính lễ có một con ngựa chín hồng mao. Vậy nó phải là con ngựa phi thường, nó phải như thế nào mới được chọn trong sính lễ. Cho đến giờ thì người xưa có nhắc đến Ngựa Hạc (lông trắng toát), Ngựa Kim (lông trắng), Ngựa Hởi (lông trắng, bốn chân đen), Ngựa Hồng (lông màu nâu –hồng), Ngựa Tía (lông màu đỏ thắm) vân vân vậy con ngựa chín hồng mao tức là phải có chín cái lông màu hồng, nó phải có nên mới có ghi chú trong truyền thuyết nhưng chắc chắn nó phải hiếm hoi như ngựa hãn huyết ((mồ hôi đỏ như máu) (Hãn huyết bảo mã)) mà được mang về Trường An bởi Trương Kiên vào năm -114 trước Công nguyên. Kích thước, tốc độ và sức mạnh của các con ngựa nầy làm hài lòng vua Hán Vũ Đế vô cùng. Ngài không ngần ngại đặt cho những con ngựa này với cái tên là « thiên mã » (tianma) (thiên mã). (thiên mã= ngựa trời). Chính vì con ngựa nầy mà Hán Vũ Đế buộc lòng phải tổ chức cuộc thám hiểm quân sự tốn hao quá mức không chỉ về trang bị và ngựa mà còn nhân mạng nửa để có một kết quả không đáng với khoảng ba mươi con thiên mã và ba nghìn con ngựa giống và ngựa cái bình thường. Nói đúng ra Hán Vũ Đế cảm thấy bị sĩ nhục trước sự từ chối cung cấp các con ngựa nầy để đổi lấy quà tặng của nước Đại Uyên (Daiyuan), một tiểu vương quốc nằm ở trong thung lũng Ferghana. Con ngựa thiên mã nầy nó trở thành biểu tượng quyền lực của Hán Vũ Đế và cũng nhờ đó mới có sự ra đời của con đường tơ lụa.

Tuy là truyền thuyết nhưng chuyện Sơn Tinh Thủy Tinh cũng nói lên một phần nào lũ lụt triên miên mà dân tộc ta phải cam chịu lúc còn cư trú ở hạ lưu sông Dương Tử (văn hóa Lương Chử) và cho đến ngày nay ở đất nước ta.

Nói đến ngựa chúng ta cũng không quên nhắc đến « Trảm Mã Trà ». Đây là một loại trà đước chế biến từ búp trà lên men trong bao tử ngựa khiến nó có hương vị đặc biệt và làm giảm đi độ chát. Cách chế biến nầy được xuất phát từ núi Vu Sơn ở Tứ Xuyên. Để lấy được trà này, người ta phải bỏ đói ngựa vài ngày trước. Khi đến chân núi Vu Sơn thì ngựa được người thả ra. Bị bỏ đói gặp được rừng trà xanh non thì ngựa vội vã ăn cho tới khi no bụng. Sau đó, con ngựa bị lùa ra khe suối gần núi. Suối ở đây hay th ường có lá trà rụng xuống khiến lá bị nát mủn nên nước suối có màu đen và được gọi là suối Ô Long. Ngựa uống nước suối xong xuôi thì được đưa trở về nơi xuất phát. Lá trà trong bụng ngựa đã ngấm đều với nước suối Ô Long và lên men sau khoảng một ngày đường đi. Lúc nầy con ngựa mới bị giết để lấy trà trong bao tử mà làm thành một loại trà độc đáo dành bán cho giới qúi tộc. Cách chế biến nầy cũng không thua chi cách chế biến gan ngỗng ở Pháp quốc nhưng cách biến chế nầy có phần cầu kỳ và kinh dị đấy.

Ai có đến Hà Nội thì sẽ có dịp đến viếng thăm đền Bạch Mã. Nó tọa lạc ngày nay ở phố Hàng Buồm. Đây là một trong tứ trấn của thành Thăng Long xưa: Đền Quán Thánh (trấn giữ phía Bắc kinh thành), Đền Kim Liên (trấn giữ phía Nam kinh thành), Đền Voi Phục (trấn giữ phía Tây kinh thành) và Đền Bạch Mã ((trấn giữ phía Đông). Nó được xây dựng từ thế kỷ 9 để thờ thần Long Đỗ (Rốn Rồng). Khi vua Lý Thái Tổ dởi đô từ Hoa Lư về Thăng Long thì ngài có ý đắp thành cho vững chắc nhưng lúc nào thành cũng bị sụp nên vua sai người đi cầu khẩn thần Long Đỗ ở đền thì thấy một con ngựa trắng ở trong đền đi ra. Nhờ theo vết chân của ngựa, vua mới xây được thành vững chắc. Vua Lý Thái Tổ mới phong thần làm thành hoàng của kinh thành Thăng Long.

Trong sách chữ Hán lại có câu: « Hồ Mã tê Bắc phong; Việt điểu sào Nam chi » có nghĩa là: Ngựa đất Hồ vào miền Trung nguyên thấy gió bắc thổi thì hí lên còn chim đất Việt vào miền Trung nguyên vẫn làm tổ ở cành phía Nam. Theo truyền thuyết thì ngoài lễ sính vật như vàng ngọc châu báu, voi, tê giác, Hùng Vương còn biếu cho vua Tàu một con bạch trĩ. Con nầy đựợc nuôi trong vườn thượng uyển. Lúc nào nó cũng kiếm đậu ở các cành cây hướng về phía nam. Bởi vậy mới có thành ngữ « Chim Việt đậu cành Nam » để ám chỉ người Việt dù ở nơi nào đi nữa lúc nào cũng nhớ quê hương và nước non. Còn con ngựa Hồ, đây là một phẩm cống mà Hán Vũ Đế nhận được từ nước Hồ nằm phía bắc Trung Hoa. Nó cứ buồn rầu không ăn uống chi cả chỉ khi có gió bắc thì nó hí lên một cách thảm thiết.

Như ta được biết ngựa rất trung thành với chủ nhân cũng như chó. Bởi vậy ở Việt Nam nơi nào có chùa của người Hoa thì có thờ Quan Vũ, một vị tướng nổi tiếng thời Tam Quốc thì bên cạnh ông luôn luôn có một con ngựa đựợc tạc tượng tên lả Xích Thố. Con ngựa nầy theo ông lập nhiều chiến công. Đến khi Quan Vũ bị giết, con ngựa Xich Thố này bỏ ăn rồi chết theo. Từ nay ngựa Xích Thố trong văn hóa dân gian lại gắn liền với hình tượng nhân vật Quan Vũ (Quan Công).

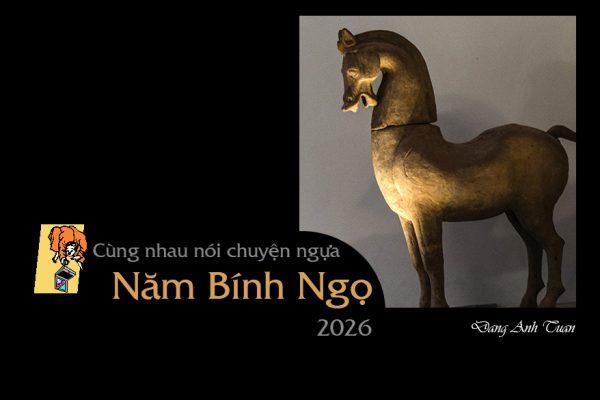

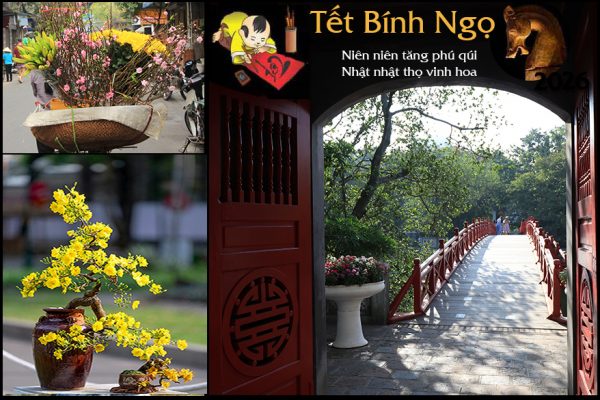

Mỗi năm được tượng trưng bởi một con vật trong Âm lịch nước ta. Như vây năm 2026 là năm con ngựa (hay Ngọ) được chọn trong 12 con vật. Theo thuật số thì có 4 con vật xung khắc với nhau trong các năm tuổi như đã quy đinh trong câu: « Tý Ngọ Mẹo Dậu tứ hành xung ». Như vậy ai mà tuổi ngọ năm nay là cái tuổi đang nhiều vận hạn mà còn xung khắc với các năm Mẹo, Dậu và Tý.

Ở Việt Nam nhất là ở trong Nam hay thường dung chữ «ngựa » để ám chỉ các phụ nữ hư thân mất nết hay dữ tợn, lúc nào cũng lồng lên như ngựa thượng tứ. Ngựa nầy xuất phát từ cửa Thượng Tứ ở Huế, nơi có cái trại nuôi ngựa của hoàng gia. Ngựa nuôi ở đây là loại ngựa chiến, rất dữ tợn, lúc nào rừng rực nhất là với mùa hứng tình lồng lộn ưa hí. Bởi vậy mới có sự kết hợp giữa từ đĩ của miền Bắc và từ ngựa Thượng Tứ ở miền Trung để rồi trở thành từ đó cái thói quen, lối chưởi của người miền Nam đế nói lên sự khinh miệt đối với các phụ nữ mất nết na thùy mị và đoan trang.

Version française

Le cheval est un animal dont on ne sait pas depuis quand il a été conquis, élevé et domestiqué par l’homme, ce qui en a fait depuis lors un bétail utile dans tous les types de déplacement, de transport et de guerre. C’est un animal non seulement fort et résistant, mais aussi très fidèle à son maître, ce qui en fait une arme redoutable dans la cavalerie. De nombreuses victoires glorieuses de notre pays ont été remportées grâce aux chevaux. C’est pourquoi nos rois ont souvent rendu hommage au passé en sculptant des chevaux et des éléphants en bronze ou en pierre ainsi que des mandarins et des soldats civils et militaires, pour commémorer les périodes glorieuses de la résistance de notre nation contre les envahisseurs étrangers.

L’homme et le cheval sont inséparables en temps de guerre, partageant les difficultés et le même destin. La poétesse Đoàn Thị Điểm a rappelé cet événement dans « Chinh Phụ Ngâm (La complainte de la femme d’un guerrier) » comme suit:

Le souffle du vent froid froisse le visage impassible

Dans l’eau profonde, le cheval découragé peine à s’avancer.

S’appuyant sur un coussin vide avec la selle posée dessus, il a été épuisé.

Couché sur les dunes de sable blanc, il dort au milieu de monticules verdoyants et moussus.

Étant de retour dans la capitale après sa victoire contre les envahisseurs mongols et voyant les chevaux de pierre aux sabots couverts de boue devant la porte Ngọ Môn, l’empereur émérite Trần Thánh Tông s’exclama dans les deux vers suivants lors de la cérémonie d’offrande :

La nation a été ballottée deux fois par des chevaux de pierre,

Les montagnes et les rivières resteront inébranlables pour l’éternité.

Dans les légendes vietnamiennes, les chevaux sont mentionnés à deux reprises. La première fois, c’est dans la légende de Saint Gióng, également connu sous le nom de Phù Đổng Thiên Vương. Sous le règne du roi Hùng Vương VI, les puissants envahisseurs Yin-Shang venus de Chine déferlèrent sur leterritoire vietnamien. Le roi fut contraint d’envoyer des messagers à travers le pays afin de recruter des personnes talentueuses capables d’aider la nation à repousser les envahisseurs. À cette époque, dans le village de Phù Đổng de la province de Bắc Ninh, un bébé, encore dans son berceau, entendit les messagers parcourir le pays, recrutant des hommes pour voir si quelqu’un pourrait vaincre les envahisseurs, et leur promettant titres et récompenses. Le bébé se réveilla et interrogea sa mère, qui lui expliqua la situation.

Selon le récit du Việt Điển U Linh, saint Gióng dit : « Mère, apporte-moi du riz en abondance. » Il n’en mangea que quelques bols. Quelques mois plus tard, il grandit et se porta volontaire pour la guerre. Surpris, le messager le conduisit à la capitale. À sa demande, le roi fit forger un cheval de fer et un long fouet. Après avoir mangé plusieurs paniers de riz fraîchement cuit, il s’étira et grandit jusqu’à atteindre plus de dix mètres. Puis il sauta alors sur le dos du cheval. En s’emparant du fouet, il cria : « Je suis un général céleste ! » et il galopa droit vers le champ de bataille.

Là, il brandit son fouet et il tua ainsi d’innombrables soldats ennemis avec son cheval crachant du feu,. Son bâton se brisa, ce qui l’obligea à déraciner des bambous pour poursuivre le combat et il dispersa l’armée Yin dans toutes les directions. Puis, il lança le cheval vers le mont Sóc Sơn et il disparut. En se souvenant de sa bravoure, le roi Hùng ordonna la construction d’un temple dans le village de Phù Đổng, district de Gia Lâm, près de Hanoï. Chaque année, un festival est organisé en son honneur le huitième jour du quatrième mois lunaire.

Nous devons nous rappeler que notre pays était très vaste à cette époque, appelé Văn Lang, bordé à l’est par la mer du Sud (Guangdong), à l’ouest par Ba Thục (ou Sichuan), au nord par le lac Dongting (Hunan) et au sud par le royaume de Hồ Tôn, c’est-à-dire Chiêm Thành (Chămpa). Notre peuple appartenait au groupe ethnique Bai Yue, encore vivant à cette époque dans la région du fleuve Yangtsé en Chine.

Dans le Livre des Mutations traduit par le professeur Bùi Văn Nguyên, l’auteur parle d’une expédition militaire menée pendant trois ans par le roi belliqueux de la dynastie Yin-Shang nommé Wu Ding dans la région du lac Dongting (Jingzhou) contre des peuples nomades, souvent appelés « Qủi ». Bien que ce soit une légende, grâce aux récentes fouilles archéologiques et aux tests ADN, cette légende n’est pas une fable mais témoigne d’un conflit entre notre peuple et la dynastie Yin. C’est pourquoi le royaume de Văn Lang n’a établi aucune relation commerciale avec la dynastie Yin-Shang à cette époque.

La deuxième fois, le cheval est mentionné dans la légende de Sơn Tinh et Thủy Tinh. Dans cette légende, le 18ème roi Hùng a une fille nommée Mị Nương, d’une beauté exceptionnelle. À l’âge de se marier, sa renommée s’étend dans toutes les directions. Le roi décide de lui choisir un mari talentueux. À ce moment-là, deux jeunes hommes, intelligents et beaux, arrivent par hasard en même temps et demandent la main de Mị Nương. L’un est appelé Sơn Tinh, seigneur des montagnes et des forêts profondes, et l’autre est Thủy Tinh, seigneur des rivières et des vastes océans.

Après trois jours et trois nuits, Thủy Tinh battu davantage chaque jour, fut obligé de retirer ses troupes et ramener les flots. Pour assurer sa tranquillité Sơn Tinh opéra le miracle d’élever les deux montagnes des époux au plus haut dans l’endroit des demeures des Dieux. Plus tard, le peuple les appellera Montagne du Monsieur et Montagne de la Dame, au pied desquelles un temple fut dédié à Sơn Tinh et à Mị Nương. Cette légende a été rapportée dans l’ouvrage intitulé » Lĩnh Nam Chích Quái (ou les contes étranges à Lĩnh Nam) » de Trần Thế Pháp sous le nom du titre « Histoire de la montagne Tản Viên ». Tous les ans vers le mois de juillet ou Août, les habitants vivant au pied de cette montagne ont l’habitude de subir le vent puissant et violent et la grande inondation provoquant ainsi des dégâts importants au niveau de la récolte.

Dans la dot, il y avait un cheval aux neuf crins roses. Il devait donc être un cheval exceptionnel, il fallait qu’il soit ainsi pour être choisi dans la dot. Jusqu’à présent, les anciens ont mentionné le Cheval Grue (robe et crinière toute blanche), le Cheval Or (robe blanche), le Cheval Hởi (robe blanche, quatre pattes noires), le Cheval Rose (robe de couleur brun-rose), le Cheval Pourpre (robe de couleur rouge vif), etc. Ainsi, le cheval aux neuf crins roses signifie qu’il doit posséder neuf crins de couleur rose. Il devait en avoir ainsi pour être signalé dans la légende, mais il est certain qu’il devait être rare comme le cheval suant du sang (Hãn huyết bảo mã) que Zhang Qian ramena à Chang An en l’an 114 avant J.-C. La taille, la vitesse et la force de ces chevaux contentèrent énormément l’empereur Han Wudi. Il n’hésita pas à donner à ces chevaux le nom de « tianma » (cheval céleste). (tianma = cheval du ciel). C’est à cause de ce cheval que l’empereur Han Wudi fut contraint d’organiser une expédition militaire extrêmement coûteuse, non seulement en équipement et en chevaux, mais aussi en vies humaines, pour un résultat qui ne valait pas la peine, avec environ trente chevaux célestes et trois mille chevaux reproducteurs et juments ordinaires. En réalité, l’empereur Han Wudi se sentit humilié par le refus de fournir ces chevaux en échange de cadeaux du royaume de Daiyuan, un petit royaume situé dans la vallée de Ferghana. Ce cheval céleste devint un symbole de pouvoir pour l’empereur Han Wudi et c’est grâce à lui que la route de la soie vit le jour.

En parlant des chevaux, nous ne pouvons pas oublier de mentionner le « Trảm Mã Trà (décapiter le cheval pour l’obtention du thé) ». C’est un type de thé fabriqué à partir de bourgeons de thé fermentés dans l’estomac d’un cheval, ce qui lui confère une saveur particulière réduisant ainsi l’astringence. Cette méthode de préparation provient de la montagne Wushan (Vũ Sơn) dans le Sichuan. Pour obtenir ce thé, on doit affamer le cheval durant quelques jours au préalable. Arrivés au pied de la montagne Wushan, le cheval est relâché par les hommes. Affamé, il se précipite pour manger les jeunes feuilles de thé vert jusqu’à ce qu’il soit rassasié. Ensuite, le cheval est conduit vers un ruisseau près de la montagne. Ce ruisseau contient souvent des feuilles de thé tombées qui se désagrègent et donnent à l’eau une couleur noire. Ce ruisseau est connu sous le nom » Ô Long« . Après avoir bu cette eau, le cheval est ramené à son point de départ. Les feuilles de thé dans l’estomac du cheval ont absorbé l’eau du ruisseau Ô Long et ont fermenté pendant environ une journée de voyage. C’est alors que le cheval est abattu pour récupérer le thé dans son estomac. Ce thé est transformé en un thé unique destiné à la vente aux nobles. Cette méthode de préparation n’est pas moins raffinée que celle du foie gras en France, mais elle est quelque peu complexe et macabre.

Quiconque visite Hanoï aura l’occasion de découvrir le temple Bạch Mã (Cheval Blanc), situé aujourd’hui à la rue Hàng Buồm (Rue des voiles). Il fait partie des quatre temples gardiens de l’ancienne citadelle de Thăng Long: le temple Quan Thánh (gardien du nord de la citadelle), le temple Kim Liên (gardien du sud), le temple Voi Phục (gardien de l’Ouest) et le temple Bạch Mã (gardien de l’Est). Il fut construit au IXème siècle en l’honneur du génie Long Đỗ (Nom du Dragon).

Lors du transfert de la capitale de Hoa Lư à Thăng Long, le roi Lý Thái Tổ souhaita y bâtir une citadelle imprenable mais celle-ci s’effondrait sans cesse. Il envoya alors des hommes d’aller prier le génie Long Đỗ au temple. Ils y virent l’apparition d’un cheval blanc. En suivant ses empreintes laissées par cet équidé dans sa marche, ils réussirent à édifier solidement la citadelle. Lý Thái Tổ conféra désormais à ce génie le titre de dieu tutélaire de Thăng Long.

Dans les livres en caractères chinois, il y a une phrase : « Hồ Mã tê Bắc phong ; Việt điểu sào Nam chi » qui signifie : Le cheval du pays des Hồ, arrivé dans la plaine centrale, hennit quand il sent le vent du nord tandis que l’oiseau du pays des Vietnamiens se trouvant dans la même plaine, fait toujours son nid sur la branche du sud. Selon la légende, en plus des offrandes comme l’or, les bijoux précieux, les éléphants et les rhinocéros, le roi Hùng a également offert au roi chinois un faisan blanc. Ce dernier était élevé dans un jardin impérial. Il cherchait toujours à se percher sur les branches orientées vers le sud. C’est ainsi qu’est née l’expression « L’oiseau des Vietnamiens se perche sur la branche du sud » faisant référence au fait que les Vietnamiens où qu’ils soient, n’oublient jamais leur pays natal et leur patrie. Quant au cheval des Hồ, il s’agit bien d’un tribut que l’empereur Han Wudi a reçu du royaume des Hồ, situé au nord de la Chine. Cet équidé triste, ne mangeait rien, et ne hennissait que d’une manière lamentable lorsqu’il y avait le souffle du vent venant du nord.

Comme chacun sait, le cheval est aussi fidèle à son propriétaire comme le chien. C’est pourquoi, au Vietnam, à proximité de chaque temple chinois, se dresse toujours une statue de Guan Yu, le célèbre général de l’époque des Trois Royaumes. Son cheval nommé Xích Thố, l’accompagna dans de nombreuses victoires. À la mort de Guan Yu, le cheval Xích Thố cessa de s’alimenter et mourut avec lui. Dès lors, dans le folklore, le cheval Xích Thố fut associé à l’image de Guan Yu (Guan Gong).

Dans le calendrier lunaire vietnamien, chaque année est symbolisée par un animal. Ainsi, 2026 est l’année du Cheval (ou Ngọ), choisie parmi les douze animaux. Selon la numérologie, quatre animaux sont en conflit au cours des années zodiacales, comme l’indique le proverbe : « Tý, Ngọ, Mẹo, Dậu sont les quatre animaux antagonistes (Rat, Cheval, Chat, Coq). » Par conséquent, les personnes nées sous l’année du Cheval connaissent de nombreux malheurs et sont également en conflit avec les années des animaux Mẹo (Chat), Dậu (Coq) et Tý (Rat).

Au Vietnam, surtout dans le sud, on utilise souvent le mot « cheval » pour désigner les femmes débauchées, sans morale ou méchantes, toujours en colère comme un cheval de Thượng Tứ. Ce cheval vient de la porte Thượng Tứ à Huế, où se trouvait un lieu d’élevage de chevaux de la royauté. Ceux-ci sont des chevaux de guerre, très féroces, toujours les plus excités surtout pendant la saison des amours où ils hennissent bruyamment. C’est pourquoi il y a une combinaison entre le mot « prostituée » du Nord et le mot « cheval de Thượng Tứ » du Centre, qui est devenue ainsi cette habitude, cette manière d’insulter des gens du Sud pour exprimer leur mépris envers les femmes sans morale.

Version anglaise

The horse is an animal whose conquest, breeding, and domestication by man are of unknown antiquity, which has since made it a useful beast for all kinds of travel, transport, and war. It is an animal not only strong and hardy, but also very loyal to its master, which makes it a formidable weapon in the cavalry. Many of our country’s glorious victories were won thanks to horses. That is why our kings often paid tribute to the past by sculpting horses and elephants in bronze or stone as well as mandarins and civil and military soldiers, to commemorate the glorious periods of our nation’s resistance against foreign invaders.

Man and horse are inseparable in wartime, sharing hardships and the same fate. The poet Đoàn Thị Điểm recalled this event in “Chinh Phụ Ngâm (The Lament of the Soldier’s Wife)” as follows:

The breath of the cold wind wrinkles the impassive face

In the deep water, the discouraged horse struggles to move forward.

Leaning on an empty cushion with the saddle placed on it, it is exhausted.

Lying on the white sand dunes, it sleeps amid verdant, mossy mounds.

Back in the capital after his victory against the Mongol invaders and seeing the stone horses with mud-covered hooves in front of the Ngọ Môn gate, the retired emperor Trần Thánh Tông exclaimed the following two lines during the offering ceremony:

The nation has been tossed twice by stone horses,

The mountains and rivers will remain unshakable for eternity.

In Vietnamese legends, horses are mentioned twice. The first time is in the legend of Saint Gióng, also known as Phù Đổng Thiên Vương. During the reign of King Hùng Vương VI, the powerful Yin-Shang invaders from China swept over Vietnamese territory. The king was forced to send messengers throughout the country to recruit talented people capable of helping the nation repel the invaders. At that time, in the village of Phù Đổng in Bắc Ninh province, a baby, still in his cradle, heard the messengers traveling the country, recruiting men to see if anyone could defeat the invaders, and promising them titles and rewards. The baby woke and questioned his mother, who explained the situation to him.

According to the account in Việt Điển U Linh, Saint Gióng said: « Mother, bring me abundant rice. » He ate only a few bowls. A few months later, he grew up and volunteered for the war. Surprised, the messenger took him to the capital. At his request, the king had an iron horse and a long whip forged. After eating several baskets of freshly cooked rice, he stretched and grew until he reached more than ten meters. Then he jumped onto the horse’s back. Seizing the whip, he cried, « I am a celestial general! » and he galloped straight toward the battlefield.

There, he brandished his whip and thus killed countless enemy soldiers with his horse spitting fire. His staff broke, which forced him to uproot bamboos to continue the fight and he scattered the Yin army in all directions. Then, he sent the horse toward Sóc Sơn Mountain and disappeared. In remembrance of his bravery, King Hùng ordered the construction of a temple in the village of Phù Đổng, Gia Lâm district, near Hanoi. Each year, a festival is held in his honor on the eighth day of the fourth lunar month.

We must remember that our country was very vast at that time, called Văn Lang, bordered on the east by the South Sea (Guangdong), on the west by Ba Thục (or Sichuan), to the north by Dongting Lake (Hunan) and to the south by the kingdom of Hồ Tôn, that is Chiêm Thành (Chămpa). Our people belonged to the Bai Yue ethnic group, still living at that time in the Yangtze River region of China.

In the Book of Changes translated by Professor Bùi Văn Nguyên, the author speaks of a military expedition lasting three years led by the warlike king of the Yin-Shang dynasty named Wu Ding in the Dongting Lake (Jingzhou) region against nomadic peoples, often called « Qủi« . Although it is a legend, thanks to recent archaeological excavations and DNA tests, this legend is not a fable but attests to a conflict between our people and the Yin dynasty. That is why the kingdom of Văn Lang established no commercial relations with the Yin-Shang dynasty at that time.

The second time, the horse is mentioned in the legend of Sơn Tinh and Thủy Tinh. In this legend, the 18th King Hùng has a daughter named Mị Nương, of exceptional beauty. At marriageable age, her renown spreads in all directions. The king decides to choose a talented husband for her. At that moment, two young men, intelligent and handsome, happen to arrive at the same time and ask for Mị Nương’s hand. One is called Sơn Tinh, lord of the mountains and deep forests, and the other is Thủy Tinh, lord of the rivers and vast oceans.

After three days and three nights, Thủy Tinh, beaten more each day, was forced to withdraw his troops and bring back the floods. To ensure his peace, Sơn Tinh performed the miracle of raising the two husband-and-wife mountains to the highest place among the abodes of the Gods. Later, the people would call them the Mister Mountain and the Miss Mountain, at the foot of which a temple was dedicated to Sơn Tinh and Mị Nương. This legend was recorded in the work entitled « Lĩnh Nam Chích Quái (or the strange tales of Lĩnh Nam) » by Trần Thế Pháp under the title « The Story of Tản Viên Mountain« . Every year around July or August, the inhabitants living at the foot of this mountain are accustomed to enduring powerful and violent winds and great flooding, thus causing significant damage to the crops.

In the dowry, there was a horse with nine pink manes. It therefore had to be an exceptional horse; it had to be like that to be chosen as part of the dowry. To this day, the elders have mentioned the Crane Horse (coat and mane all white), the Gold Horse (white coat), the Hởi Horse (white coat, four black legs), the Pink Horse (brown-pink colored coat), the Purple Horse (bright red colored coat), etc. Thus, the horse with nine pink manes means that it must have nine manes of pink color.

He must have been such to be noted in legend, but it is certain that he must have been rare like the blood-sweating horse (Hãn huyết bảo mã) that Zhang Qian brought back to Chang’an in 114 BC. The size, speed and strength of these horses greatly pleased Emperor Han Wudi. He did not hesitate to give these horses the name « tianma » (heavenly horse). (tianma = horse of the sky). It was because of this horse that Emperor Han Wudi was forced to organize an extremely costly military expedition, not only in equipment and horses, but also in human lives, for a result that was not worth it, with about thirty heavenly horses and three thousand breeding stallions and ordinary mares. In reality, Emperor Han Wudi felt humiliated by the refusal to provide these horses in exchange for gifts from the kingdom of Dayuan, a small kingdom located in the Ferghana valley. This heavenly horse became a symbol of power for Emperor Han Wudi and it is thanks to it that the Silk Road came into being.

Speaking of horses, we cannot forget to mention « Trảm Mã Trà (decapitate the horse to obtain the tea). » It is a type of tea made from tea buds fermented in the stomach of a horse, which gives it a particular flavor that reduces astringency. This preparation method comes from Wushan (Vũ Sơn) mountain in Sichuan. To obtain this tea, the horse must be starved for a few days beforehand. Upon reaching the foot of Wushan mountain, the horse is released by the men. Hungry, it rushes to eat the young green tea leaves until it is full. Then the horse is led to a stream near the mountain. This stream often contains fallen tea leaves that break down and give the water a black color. This stream is known as « Ô Long. » After drinking this water, the horse is returned to its starting point. The tea leaves in the horse’s stomach have absorbed the water from the Ô Long stream and fermented during about a day’s travel. It is then that the horse is slaughtered to retrieve the tea from its stomach. This tea is processed into a unique tea intended for sale to nobles. This preparation method is no less refined than foie gras in France, but it is somewhat complex and macabre.

Anyone who visits Hanoi will have the opportunity to discover the Bạch Mã (White Horse) Temple, now located on Hàng Buồm Street (Sail Street). It is one of the four guardian temples of the former citadel of Thăng Long: the Quan Thánh Temple (guardian of the north of the citadel), the Kim Liên Temple (guardian of the south), the Voi Phục Temple (guardian of the west) and the Bạch Mã Temple (guardian of the east). It was built in the 9th century in honor of the spirit Long Đỗ (Dragon’s Name).

When the capital was moved from Hoa Lư to Thăng Long, King Lý Thái Tổ wished to build an impregnable citadel but it kept collapsing. He then sent men to pray to the spirit Long Đỗ at the temple. They saw the appearance of a white horse. By following the footprints left by this animal as it walked, they succeeded in solidly erecting the citadel. Lý Thái Tổ thereafter conferred on this spirit the title of tutelary deity of Thăng Long.

In books written in Chinese characters, there is a sentence: « Hồ Mã tê Bắc phong; Việt điểu sào Nam chi » which means: The horse of the land of Hồ, arriving on the central plain, neighs when it feels the north wind, while the bird of the land of the Vietnamese, being on the same plain, always builds its nest on the southern branch. According to legend, in addition to offerings such as gold, precious jewels, elephants and rhinoceroses, King Hùng also gave the Chinese king a white pheasant. The latter was raised in an imperial garden. It always sought to perch on branches facing south. Thus was born the expression « The bird of the Vietnamese perches on the southern branch » referring to the fact that the Vietnamese, wherever they are, never forget their native land and homeland. As for the horse of the Hồ, it was indeed a tribute that Emperor Han Wudi received from the kingdom of Hồ, located north of China. This sorrowful steed ate nothing, and only neighed in a lamentable way when there was the breath of wind coming from the north.

As everyone knows, the horse is as loyal to its owner as the dog. That is why, in Vietnam, near every Chinese temple, there is always a statue of Guan Yu, the famous general from the Three Kingdoms era. His horse named Xích Thố accompanied him in many victories. At Guan Yu’s death, the horse Xích Thố stopped eating and died with him. Since then, in folklore, the horse Xích Thố has been associated with the image of Guan Yu (Guan Gong).

In the Vietnamese lunar calendar, each year is symbolized by an animal. Thus, 2026 is the Year of the Horse (or Ngọ), chosen among the twelve animals. According to numerology, four animals are in conflict during the zodiac years, as the proverb indicates: « Tý, Ngọ, Mẹo, Dậu are the four antagonistic animals (Rat, Horse, Cat, Rooster). » Therefore, people born in the Year of the Horse experience many misfortunes and are also in conflict with the years of the animals Mẹo (Cat), Dậu (Rooster) and Tý (Rat).

In Vietnam, especially in the South, the word « horse » is often used to refer to dissolute, immoral, or mean women, always angry like a Thượng Tứ horse. This horse comes from the Thượng Tứ gate in Huế, where there was a royal horse breeding farm. These are war horses, very fierce, always the most excited especially during the mating season when they neigh loudly. That is why there is a combination between the word « prostitute » from the North and the word « Thượng Tứ horse » from the Central region, which has thus become this habit, this way of insulting people from the South to express their contempt for immoral women.

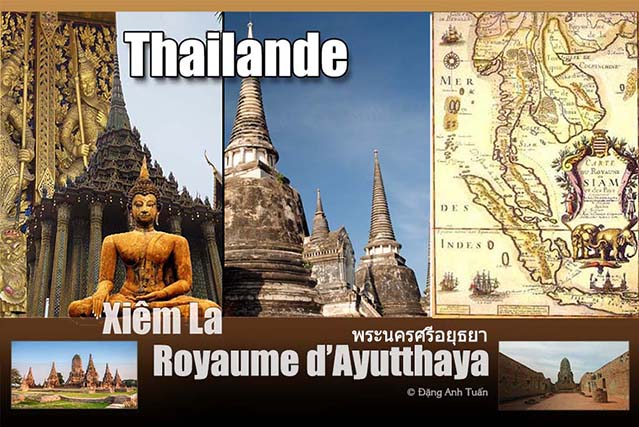

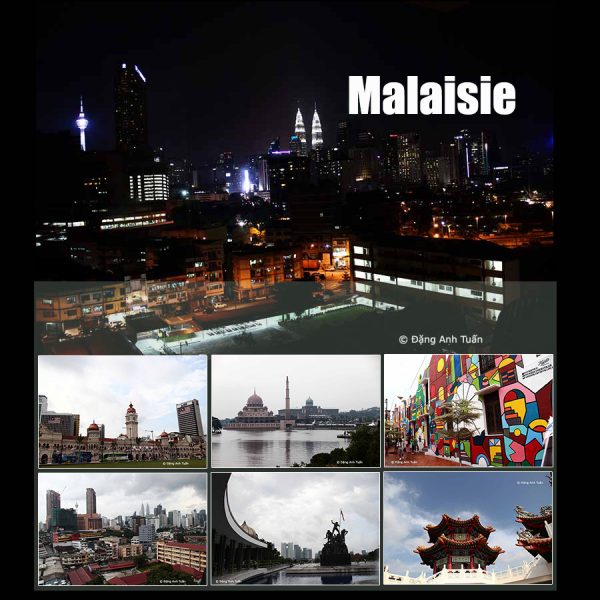

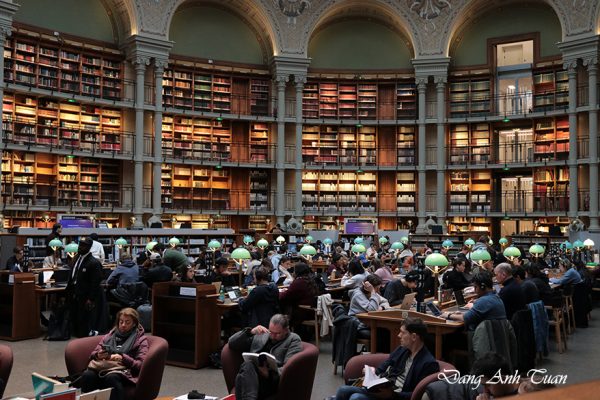

Galerie des photos

[Return TET BÍNH NGỌ]