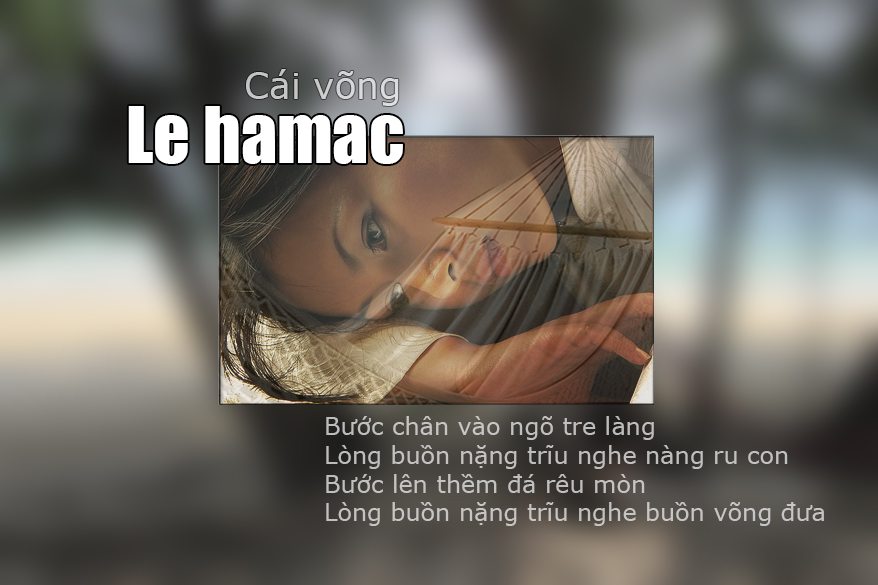

Trong cunq quế âm thầm chiếc bóng

Ðêm năm canh trông ngóng lần lần

Khoảnh làm chi bầy chúa xuân

Chơi hoa cho rữa nhị dần lại thôi.

In the royal genaeceum, I stay alone with my shadow,

All night long, I eagerly wait for his visit.

Instantly, many springs have gone by,

He ceased coming in as this flower is withering.

Ôn Như Hầu

Except Gia Long, the founder and Bảo Ðại, the last emperor of the Nguyen dynasty no emperors of this dynasty granted a title to their principal spouse during their reign. No historic documents found today show why there was that systematic refusal since the application of Minh Mang’s decree. On the contrary, only this spouse received her title after her disappearance.

First imperial concubine ( Nhất giai Phi ) ( 1st rank )

Second imperial concubine ( Nhị Giai Phi ) ( 2nd rank )

Superior concubines ( from 3rd to 4th rank ) (Tam Giai Tân và Tứ Giai Tân ), simples concubines ( from 5th to 9th rank ) ( Ngũ Giai Tiếp Dư , Lục Giai Tiếp Dư, Thất Giai Quí Nhân, Bát Giai Mỹ Nhân, Cữu Giai Tài Nhân ).

Then came the Ladies of the Court, next, the subordinate servants. It was estimated that those women along with the eunuchs, the queen mothers and the emperor made up a purple forbidden society of Huế. The status of those women (even that of the servants) no matter what it was, went up considerably when they gave birth to a son.

Speaking of those concubines, it is impossible not to evoke the love story of Nguyễn Phi, the future empress Thừa Thiên Cao Hoàng Hậu with prince Nguyễn Ánh, the future emperor Gia Long. This one, beaten by the Tây Sơn (or the peasants of the West) in the Fall of 1783, had to take refuge on the Phú Quốc Island. He had to send his son Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh, 4 years old, accompanied by archbishop Pigneau de Behaine to France to ask for military aid before king Louis XVI (Treaty of Versailles 1787), and took refuge in Bangkok ( Thailand) waiting for French reinforcement. Before the time of separation, he hastened to cut a gold bar into two halves and gave one to his spouse, Nguyễn Phi telling her:

Our son has already gone. I am about to leave you to resettle in Thailand. You stay here to take care of our queen mother. I do not know the date of my return nor the place of our reunion . I leave with you this half gold bar as the token of our love. We will have the chance to see each other later if God helps us to defeat the Tây Sơn.

During Nguyễn Anh’s years of exile and setback in his reconquest of power, Nguyên Phi continued to take care her mother-in-law, queen Hiếu Khương (spouse of Nguyễn Phúc Luân ) and to make uniforms for recruits. She arrived at overcoming all the difficulties destined to her family and showed her courage and bravery in escaping traps set up by their adversaries.

Thanks to his perseverance and stubbornness, Nguyễn Ánh succeeded in defeating the Tây Sơn in 1802 and became our emperor Gia Long. The day following their touching reunion, he asked her about the other half of the gold bar he had given her at the moment of their separation. She went looking for it and gave it back to him. Seeing the half of the bar in the state of shining, emperor Gia Long was so touched he told his spouse Nguyễn Phi:

This gold that you succeeded in keeping in its splendor during our difficult and eventful years shows well the blessings and grace of God for our reunion today. We should not forget that and should talk about it to our children.

Then he reassembled the two halves of the gold bar to make it whole again and gave it to Nguyễn Phi. This gold bar later became under the reign of Minh Mạng, not only the symbol of eternal love between Nguyễn Ánh and his spouse Nguyễn Phi but also an object of veneration found on the altar of emperor Gia Long and empress Thừa Thiên Cao Hoàng Hậu in the Ðiện Phụng Thiên temple in the purple city of Huê.

No one was surprised that thanks to his daughter Ngô Thị Chánh, former Tây Sơn general Ngô Vân Sở was spared from summary execution by emperor Gia Long during the victory over the Tay Son, because his daughter was the favorite concubine of his crown prince Nguyễn Phúc Ðảm, our future emperor Minh Mang. When this one acceded to power, he did not hesitate to grant her all the favors uniquely reserved up until then for his principal spouse. This concubine, when alive, often had the chance to tell the emperor:

Even you love me as such, the day I decease, I will be alone in my tomb empty-handed.

That was why when she died a few years later, the emperor followed her to the place of burial taking with him two ounces of gold. He then asked the eunuch to open the two hands of the concubine. The emperor himself put an ounces of gold in each hand saying with emotion:

I give you two ounces of gold so that you do not go empty-handed.

One found this love fifty years later in poet emperor Tự Ðức. At the funeral of his favorite concubine, he composed a poem entitled « Khóc Bằng Phi » whose two following verses immortalized love and affection emperor Tự Ðức reserved for his concubine Bằng Phi:

Ðập cổ- kính ra, tìm lấy bóng

Xếp tàn-y lại để dành hơi

I break the old mirror to find your shadow

I fold your fading clothes to keep your warmth.

Cung tần mỹ nữ

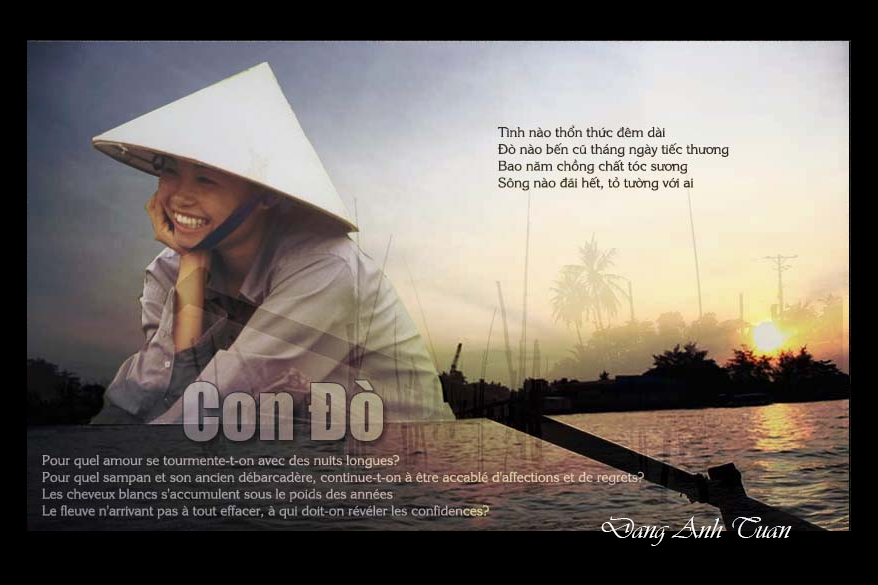

Under the Nguyen dysnasty, the genaeceum took an important dimension. To consolidate his authority and gain fidelity from his subordinates, emperor Gia Long himself did not hesitate to establish the politics of alliance in taking for concubines most of the daughter of the subordinates. This was revealed by his confidant, the French mandarin J.B. Chaigneau in his » Souvenirs of Huế 1864 « . But sometimes the concubine of the emperor may be issue of a different medium. It is the case of the concubine of emperor Thành Thái, the father of Duy Tân. This concubine was the rower of a ferry boat in the region of Kim Long known for the charm and grace of its inhabitants. That is why people did not hesitate to sing the following popular song to evoke the idyllic love that emperor Thanh Thai reserved for the charming rower of the ferry and his audacity to disguise himself as a common traveler to visit Kim Long.

Kim Long có gái mỹ miều

Trẩm yêu trẩm nhớ trẩm liều trẩm đi

Kim Long is known for its charming girls

I love, I miss, I dare and I go.

One beautiful morning of our new year, Thành Thái intrigued by the charm of the Kim Long region decided to go there alone. He disguise himself as a young traveler to visit that famous region. On his way back, he had to take the ferry the rower of which was a charming girl. Seeing her timid in gait with her red cheeks under the overwhelming sun, emperor Thành Thái began to flirt with her and tease her with this idea, saying:

Miss, do you like to marry the emperor?

Stunned by this hazardous proposal, the girl looked attentively at him and replied with sincerity: Don’t you talk nonsense, they are going to cut off you head.

Seeing her in a fearful state, the emperor was determined to bother her more: That’s right, what I have proposed with you. If you agree, I will be the intermediary in the matter! Caught by a sense of decency, she hid her face behind her arm. On the ferry, among the passengers, there was an older and well dressed person. This one, having heard their conversation, did not hesitate to push on by saying to the girl:

Miss, just say « Yes » and see what happens!

Encouraged by the daring advice, the ferry rower responded promptly: Yes Happy to know the consent of the rower, Thành Thái stood up, went toward the rower and said with tenderness:

My dear concubine, you may rest. Let me take care of rowing the ferry for you.

Everyone was surprised by that statement and finally knew that they were in front of young emperor Thành Thái, known for his anti-French activities, deposed and exiled later by the French authorities to the Reunion island because of his excess in « madness ». When the ferry reached the Nghinh Lương dock, Thành Thái ordered the passengers to pay for their tickets and led the young rower into the forbidden city.

Generally speaking, the concubines lived surrounded by Ladies of the Court, eunuchs and devoted their time in embroidering and weaving. Some died without ever having received the emperor’s favor, or having got out of the palace.

A famous poet of 18th century Nguyễn Gia Thiều known under the name of Ôn Như Hầu (because of his title), had denounced the injustice inflicted upon these women, their sadness and isolation, in his work » Cung Oán Ngâm Khúc » (or Sadness of the Palace ). Others enjoyed their status of a favorite but none was equal to Ỷ Lan, the favorite of Lý Thánh Tôn of the Lý dynasty, who had assumed brilliantly the regency of the kingdom during her husband’s campaign against Champa.