Vương triều chàm Indrapura

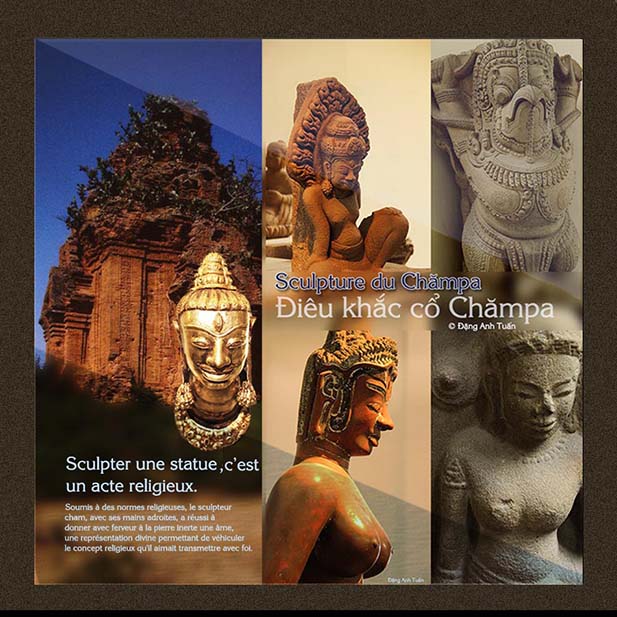

is compared to what we see today at the Champa Sculpture Museum in Da Nang.

French version

Vietnamnese version

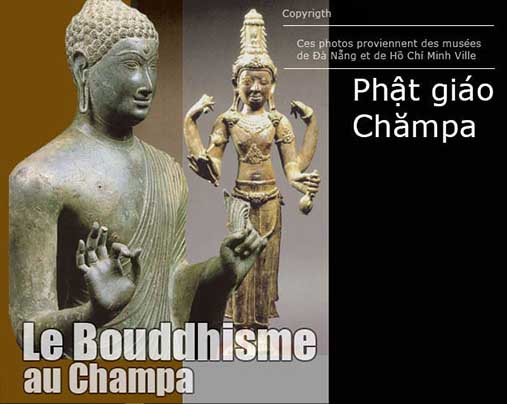

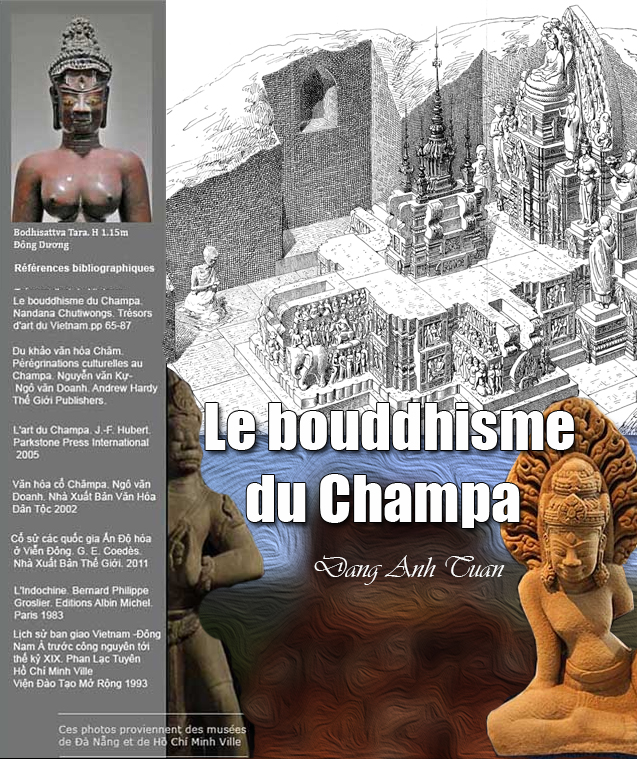

Unfortunately, for an unknown reason, its distinctive attributes were broken and confiscated by the office of the Bình Định People’s Committee, which currently oversees the Đồng Dương site. They have not been returned to the Cham Museum in Đà Nẵng to this day, despite the piece being exhibited to the public for a long time. This is why the bronze statue continues to be the subject of various iconographic interpretations. Based on the information provided (the photos) at the time he conducted an in-depth study in 1984, Jean Boisselier thought it represented Tara. For this, he tried to rely on the idols of Đại Hữu, the codification of the deity’s gestures (mudra), the rank in the Buddhist pantheon, the ornamentation of the adornments (nànàlankàravati), the importance of the gaze, and the existence of the third eye to successfully identify the deity.

Some Vietnamese researchers see in this statue the wife Lakshmi of Vishnu because one of its two distinctive attributes includes the conch (con ốc). For the Vietnamese researcher Ngô Văn Doanh, there is no doubt about the identity of this deity. It is indeed Laksmindra-Lokesvara because, for him, each distinctive attribute has a particular meaning. The lotus symbolizes beauty and purity. As for the conch, it symbolizes the propagation of Buddha’s teaching and awakening after the sleep of ignorance.

This is also the hypothesis long accepted by Vietnamese researchers. According to the Thai specialist Nanda Chutiwongs, this magnificent bronze is called Prajnàpàramità (Perfection of Wisdom). But this does not diminish the conviction of most specialists who, like Jean Boisselier, continue to see in this exceptional bronze the alluring goddess Tara, whose heavy breasts remain one of the prominent features found in her early youth. She is always the consort of the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara.

Recently, in the report on archaeology that took place in 2019 in Hanoi, researchers Trần Kỳ Phương and Nguyễn Thị Tú Anh had the opportunity to redefine the name of the bronze statue, Tara, based on the decorative image of the Buddha found in the statue’s hair, the distinctive attributes (the lotus and the conch) in her two hands, as well as the hand gesture. According to these Vietnamese researchers, Tara is the female incarnation of the meditation Buddha Amoghasiddhi, heir of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni in tantric Buddhism (Tibet).

He was often seated under the fan spread by the seven-headed cobra Mucalinda, known as « Effective Success. » In iconography, he often held a sword in his left hand and a significant gesture recognizable under the term « Abhayamudra (or absence of fear) » in his right hand during his meditation.

That is why the decorative image of the small Buddha, corresponding exactly to what is described, is found on the hair of the bronze statue. Moreover, this statue is green in color all over the body. This is also the identity of the dhyani Buddha Amoghasiddhi. If the lotus symbolizes purity, the conch and the gesture of his hand under the conch correspond well to the dharmacakra mudra, setting in motion the wheel of the Dharma law.

According to researchers Trần Kỳ Phương and Nguyễn Thị Tú Anh, the Yunnan region was once a relay zone intended to facilitate the spread of Tibetan religion and art throughout Southeast Asia via the route called the « Tea and Horse Road. » It was also the place where tantric Buddhism was revered by everyone, from the people to the king, and where the production of bronze bodhisattvas Lokesvara and Tara destined for Southeast Asia was extremely important from the 7th or 8th century onward.

That is why the veneration of the bodhisattvas Lokesvara or Tara was not unusual in Chămpa. Until now, no statue of Lokesvara has appeared or been discovered at Đồng Dương, particularly at the Buddhist monastery, because it was here that King Indravarman II erected a temple to venerate his protective Buddha Lokesvara. He even associated his own name with that of the bodhisattva Lokesvara to give this Buddhist site the name Laksmindra-Lokesvara.

That is why there is no doubt about the existence of the statue of Lokesvara. It is an enigma without explanation to this day. According to researcher Trần Kỳ Phương, it is possible that this statue was made of bronze and is the same size as that of Tara. It must have been placed on the altar at the same time as Tara’s when the honor was first given at that time. Perhaps after this glorification in its honor, it was moved elsewhere or buried in the ground because of the war.

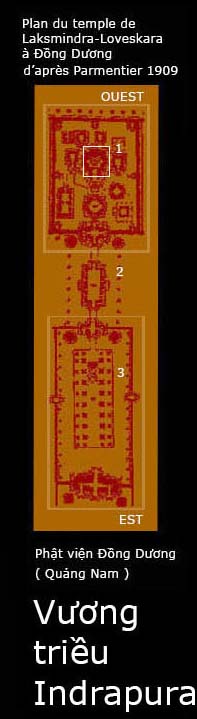

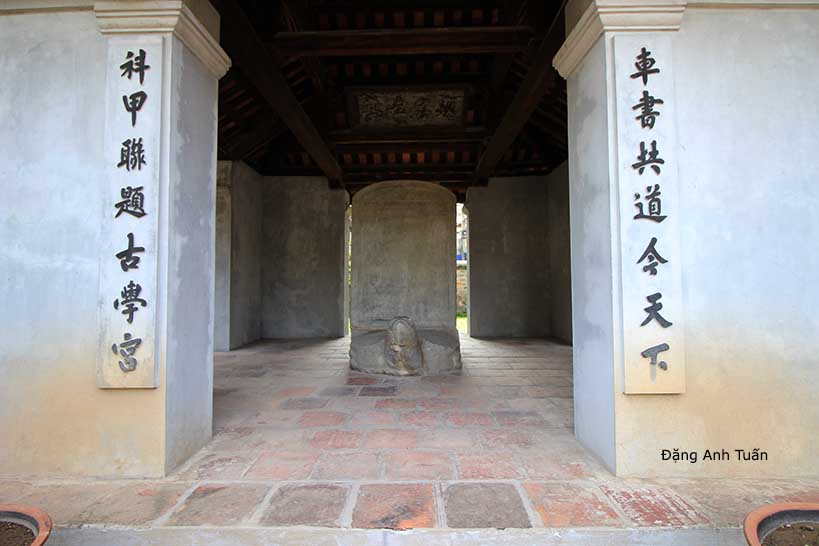

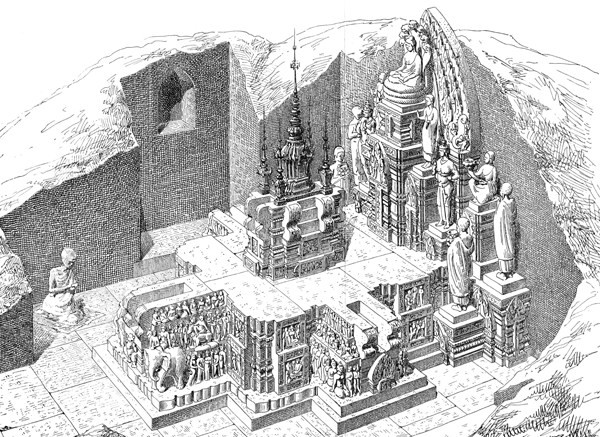

In the second enclosure, there is a long waiting hall (or mandapa) (2) that Henri Parmentier called « the hall with windows » in his description. Then, in the third enclosure (3), there is a large pillared hall, about thirty meters long. It is probably the prayer hall of the monks (vihara) where a majestic imposing statue of Buddha sits, to whom the second altar is dedicated, with a base decorated in relief and surrounded by two haloed attendants. This Buddhist site was recognized by the Vietnamese authorities as a national heritage of the country in May 2001. The blinding destruction caused by American bombing during the war years left only one intact gopura tower at this site, which the local population calls « Tháp sáng » (or tower of light) because it is open to the four directions, letting in the light. Despite this, this site continues to revive a glorious past with its great monastery, which was at one time one of the renowned religious intellectual centers in Southeast Asia. It was here that, after his brilliant victory over Champa in 985, the Vietnamese king Lê Đại Hành (or Lê Hoàn) brought back to Vietnam an Indian monk (Thiên Trúc) who was staying at this monastery. In 1069, the great Vietnamese king Lý Thánh Tôn managed to capture a famous Chinese monk, Thảo Đường, here during his victory over Champa. But it was also here in 1301 that the founding king of the Vietnamese Zen school (Phái Trúc Lâm Yên Tử), Trần Nhân Tôn, accompanied by the Vietnamese monk Đại Việt and received by the talented Cham king Jaya Simhavarman III (Chế Mân in Vietnamese), the future husband of Princess Huyền Trân, spent 9 months meditating in this religious center.

For the French researcher Jean Boisselier, Cham sculpture was always closely linked to history. Notable changes have been observed in the development of Cham sculpture, particularly statuary, in connection with historical events, changes of dynasties, or the relations that Champa had with its neighbors (Vietnam or Cambodia). That is why one cannot ignore that a change of dynasty encourages a creative momentum in the development of Cham sculpture, which is distinguished by a new particular style now known under the name « Đồng Dương. »

This one cannot go unnoticed due to its following facial features: prominent eyebrows connected in a continuous, sinuous line rising up to the hairline, thick lips with the corners turned up, a mustache sometimes mistaken for the upper lip, and a flat nose, wide from the front and aquiline in profile, a narrow forehead, and a short chin. The absence of a smile is noteworthy. This style continued to develop alongside Mahayana Buddhism in other regions of Champa under the reigns of the immediate successors of the Buddhist king Indravarman II. They continued to particularly venerate Avalokitesvara and to adopt Buddhism as the state religion. This is known from royal inscriptions. This is the case with the Ratna-Lokesvara sanctuary, which King Jaya Simhavarman I, the nephew of King Indravarman II, patronized. This sanctuary has been located at Đại Hữu in the Quảng Bình region. In this sacred place, a large number of Buddhist sculptures have been unearthed. Then around Mỹ Đức in the same province of Quảng Bình, a Buddhist complex was discovered with architectural and decorative similarities to those found at Đại Hữu and Đồng Dương.

Buddhist faith is not absent either in Phong Nha, where some caves used as places of worship still retain their imprint over the years. Finally, a temple dedicated to the deity Mahïndra-Lokesvarà was erected in 1914 in Kon Klor (Kontum) by a chief named Mahïndravarman. There were even two pilgrimages organized by a high dignitary on the orders of King Yàvadvipapura (Java) with the aim of deepening the siddhayatra (or mystical knowledge), as reported by the inscriptions of Nhan Biểu dating from 911 AD.

Cham dynasty of Indrapura

Bouddha statue, Thăng Bình, Quảng Nam

854-898 Indravarman II (Dịch-lợi Nhân-đà-la-bạt-ma)

898-903 Jaya Simharvarman I (Xà-da Tăng-gia-bạt-ma)

905-910 Bhadravarman III (Xà-da Ha-la-bạt-ma)

910-960 Indravarman III (Xà-da Nhân-đức-man)

960-971 Jaya Indravarman I (Dịch-lợi Nhân-di-bàn)

971-982 Paramesvara Varman I (Dịch-lợi Bế- Mĩ Thuế)

982-986 Indravarman IV (Dịch-lợi Nhân-đà-la-bạt-ma)

986-988 Lưu Kế Tông

989-997 Vijaya shri Harivarman II (Dịch-lợi Băng-vương-la)

997-1007 Yan Pu Ku Vijaya Shri (Thất-ly Bì-xà-da-bạt-ma)

1007-1010 Harivarman III (Dịch-lợi Ha-lê-bạt-ma)

1010-1018 Paramesvara Varman II (Thi Nặc Bài Ma Diệp)

1020-1030 Vikranta Varman II (Thi Nặc Bài Ma Diệp)

1030-1044 Jaya Simhavarman II (Sạ Đẩu)

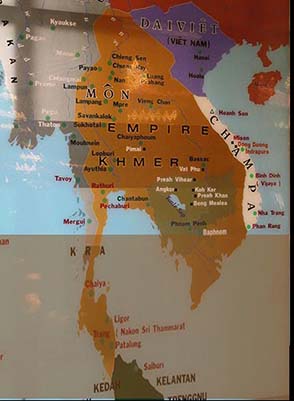

This Buddhist faith began to seriously falter in the face of the invasion of the people from the North (the Vietnamese) who had just been freed from Chinese oppression. These, led by the new king Lê Đại Hành, did not hesitate to sack the capital Indrapura in 982 after the Cham king Parameçvaravarman I (Ba Mĩ Thuế) had clumsily and for an unknown reason detained two Vietnamese emissaries Từ Mục and Ngô Tử Canh and openly supported Ngô Tiên, son of the liberator king of the Vietnamese nation, Ngô Quyền, in the power struggle.

Mahayana Buddhism did not allow the Cham kings to find everything they needed in their struggle against the Vietnamese enemies. They began to doubt the wisdom of this religion when it failed to attract the local population until then. It remained the personal religion of choice for the elites and their Cham kings. They preferred to seek their salvation in the worship of their destructive god Shiva in order to better protect their victories and to enable them to resist, more or less, the foreign invaders (Chinese, Mon, Khmer, and Vietnamese) in the creation, maintenance, and survival of their nation.

Their perpetual belligerence, probably inspired by Shaivism, became a strong argument and a legitimate justification first for the Chinese and then for the Vietnamese to carry out military interventions and gradually annex their territory in the march southward (Nam Tiến).

Bibliographic references

Avalokitesvara: name of a bodhisattva representing the infinite compassion of the Buddha.

Bodhisattva: being destined for enlightenment (Bồ tát)

Dharma: moral law (Đạo pháp)

Lokesvara: lord of the world. Designation of a Buddha or Avalokitesvara.

Mandapa: religious building with columns within the temple enclosure.

Tara: the one who saves. Female counterpart of Avalokitesvara. Highly revered in India and Tibet.

Vishnu: God who maintains the world between its creation by Brahma and its destruction by Shiva.