Phó nhòm tí hon

Le jeune photographe

Traditions vietnamiennes ou mondiales.

Những chuyện bên lề ở giữa lòng chung cư

Version française

Version anglaise

Galerie des photos

Mỗi ngày, sáng hay chiều tối nào, tụi nầy cũng có thói quen từ khi đến Viêt Nam sau khi ăn cơm hay thường la cà ngồi quán cà phê. Ngày xưa, người Việt trò chuyện hay thường bắt đầu bằng cách têm trầu nay sự việc nầy không còn mà được thay thế bằng ly cà phê. Có thể nói, gặp nhau muốn nói chuyện gì cũng được, phải có ly cà phê. Giờ phút nầy cà phê nó không thể thiếu ở người Việt, không biết lúc nào nó lại nằm trong văn hóa của người Việt. Không thể thiếu nó nhất là các quán nó đua nhau mọc lên như nấm trong khu chung cư nầy. Không biết các quán bán được bao nhiêu ly cà phê mỗi ngày mà đi qua xem vựa, nơi mà họ lưu trử các khối nước đá trông thấy ở chung cư, thấy mà khiếp sợ. Mới đây mùng hai Tết trên đường về bằng xe grab, cháu tài xế hỏi mình như sau: Chú có phiền không, cho cháu ghé uống một ly cà phê có được không ? Mình mới nói: uống đi cháu, chú đơị cháu. Nhưng nghĩ sao, cháu tài xế không uống, đưa thẳng mình về khách sạn. Lúc trả tiền, mình mới nói với cháu tài xế: Chú biếu cháu 50.000 đồng tiền lì xì (2 euros) để cháu uống cà phê đi nha. Cháu tài xế cười toe toét. Mình muốn nói đây cái sung sướng mà mình nhận được trên khuôn mặt của cháu tài xế khi nhắc đến ly cà phê.

Không nhất thiết uống nhiều ly cà phê trong ngày mới có thể ngồi ở quán, chỉ cần một ly cà phê là đủ rồi, bạn có thể ngồi nguyên ngày. Ở quán cà phê trong chung cư, dù không có thức ăn đi nữa mình có thể kêu ở các quán bán thức ăn gần đó mang đến cho mình ăn. Đây là một dịch vụ miễn phí chỉ có ở Việt Nam. Ngồi quán cà phê, tụi nầy có thể thư thản đọc sách, xem điện thọai, người hay xe cộ đi qua lại mà cũng có thể quan sát cuộc sống hằng ngày của người dân sống ở trong chung cư.

Vừa ngồi xuống nghế chưa đầy 5 phút thì có các cháu bé hay các bà mẹ bế con bán giấy số đến lần lượt xin tụi nầy mua giấy số. Nhưng làm sao mua nổi, người nào cũng có cả trăm tờ, mỗi tờ 10.000 đồng họ chỉ được 1000 đồng nếu họ bán được một tờ. Nếu bán không hết trong ngày, chiều lại không được trả lại. Như vậy họ làm sao có lời, chắc chắn họ phải mất tiền. Phải có mẹo nào đó. Cách buôn bán giấy số nầy làm mình rất phân vân, có cái gì không ổn. Dĩ nhiên làm mình chạnh lòng nhưng mình chỉ cho tiền các em nhỏ bán giấy số mà thôi chớ không mua còn anh bạn mình thi chỉ mua giấy số của các người khuyến tật, mua rồi đem tặng các bạn già ở Việt Nam. Hai đứa nầy lúc nào cũng có ở trong đầu nhiều câu hỏi nhưng chả bao giờ có câu trả lời chính đáng. Ở chung cư vì cuộc sống rất chật vật, không gian thì eo hẹp, gia đình đông con hay thường thấy họ ngủ la liệt dưới đất nên việc nấu ăn trong nhà thường ít thấy. Thông thường thấy họ la cà các quán, ăn tại chỗ hay mua về ăn. Luôn cả cô em bà con của mình ở chung cư một mình hay thường mua đồ ăn ở chợ đem về nhà mà ăn. Đôi khi cũng ngon đáo để như món mắm chưng hột vịt mà cô em thết đãi tụi nầy một hôm, làm tụi nầy nhớ hoài. Mình hay thường nghe câu nói nầy từ ông bạn mình: Thế hệ ngày nay không phải là thế hệ của má tụi mình. Phụ nữ Việt Nam không còn biết nấu ăn, chỉ biết phê bút hay sống ảo mà thôi. Cái nhận xét nầy cũng không hoàn toàn sai. Phải cần có adrenaline để quên đi sự phiền muộn trong cuộc sống mong manh.

Ở giữa lòng chung cư, có nhiều nghề sống được lắm như biết may vá, nấu ăn giỏi như cô Mai, cô Lý. Cô Mai thì nổi tiếng các món xào nhất là bà biết làm sao khi mình ăn còn mùi khói chớ không có mùi cháy của chảo như cơm chiên gà, mì xào giòn còn cô Lý thì món tầm bì nước dừa, bánh bèo bì, chè chuối vân vân phải nói quá ngon làm mình vẫn còn thèm đấy. Muốn ăn các món nầy thì phải chịu khó đợi lúc nào cũng đông khách cả. Quá giờ thì không còn nữa đấy. Họ trù liệu bao nhiêu phần để bán chớ hết thì thôi ngày hôm sau trở lại chớ không như ở Paris nhiều tiệm đỗ nước thêm để bán phở tiếp. Có một lần anh bạn mình muốn ăn thịt heo quay thôi chớ không muốn ăn bánh hỏi vì thích ăn với bánh mì nhưng họ không bán vì họ trù liệu trước bao nhiêu bánh hỏi để bán với thịt quay rồi.

Chính ở chung cư nầy mình có duyên được gặp một hôm ở quán cà phê môt họa sỹ nhỏ tuổi đang ngồi chăm chỉ vẽ cảnh vật ở chung cư với bút mực. Cháu nầy có bản năng vẽ không sữa không làm lem bức tranh với mực. Mình thích qu á chừng nên muốn mua bức tranh nhưng cháu rất dễ thương mới thốt lên như sau: Chú muốn, cháu tặng chú. Mình cũng không ngờ. Đây là duyên cháu có với chú đấy thôi. Sau đó anh bạn của mình ngỏ ý mua một tấm tranh khác để mang về Paris tặng bạn. Vui cũng có với cháu họa sỹ nầy mà buồn cũng có với em bé tạc chừng 12 tuổi ngậm xăng phun lửa thường thấy ở chung cư. Bé nầy thường biểu diễn trước đám đông ngậm xăng phun lửa. Tình cờ mình thấy vậy mới kêu em bé lại hỏi chuyện. Tại sao con làm vậy, con có biết xăng nó độc nay mai con sẽ bi ung thư cuống họng không? Con nhớ chú dặn con không nên làm nghề nầy nữa. Mình chỉ khuyên nó, thấy thương nó nên cho nó một trăm ngàn đồng, chả là bao nhiêu cả. Mình cảm thấy bất lực vì mình biết mình không thể làm gì hơn.

Ở chung cư nầy biết bao nhiêu người nghèo, mình có làm được gì không?. Cháu nhờ nghề nầy mỗi ngày cháu kiếm được vài trăm ngàn để nuôi em và sống, ba má cháu ly dị? Câu nói nầy nó vẫn còn ở trong tâm trí của mình khi mình viết về chung cư. Một con chim én đâu có đem lại mùa xuân. Nhưng không vì thế mà mình quên đi những trẻ em nghèo nầy. Chúng nó là tương lai của đất nước nầy.

Depuis notre arrivée au Vietnam, nous avons pris l’habitude de nous attarder dans un café après les repas, matin et soir. Autrefois, les Vietnamiens entamaient les conversations en commençant par la chique du bétel. Mais ce n’est plus le cas d’aujourd’hui. Elle est remplacée par une tasse de café. On peut dire sans se tromper que, quel que soit le sujet de conversation, une tasse de café s’avère indispensable. De nos jours, le café est devenu incontournable pour les Vietnamiens. Il est difficile de dire quand il est entré dans la culture vietnamienne. Il l’est d’autant plus depuis lors avec la poussée des cafés comme celle des champignons dans ce complexe d’appartements. Je me demande combien de tasses de café ces établissements vendent chaque jour, car le stockage des tonnes de glace dans le complexe est assez effarant. Récemment, le deuxième jour du Têt (Nouvel An lunaire), alors que je rentrais chez moi en taxi grab, le chauffeur m’a demandé : « Monsieur, cela vous dérangerait-il si je m’arrêtais pour prendre un café ? » J’ai répondu sans hésitation: « Allez-y, je vous attends. » Mais pour une raison inconnue, le jeune chauffeur n’en a pas bu et m’a ramené directement à l’hôtel. Au moment du paiement, j’ai dit au jeune chauffeur : « Voici 50 000 dongs ( à peu près 2 euros) en cadeau de notre Nouvel An pour vous offrir un café. » Il m’a montré un large sourire. Je voulais souligner la joie que j’avais vue sur son visage à l’évocation du café.

Il n’est pas nécessaire de boire plusieurs tasses de café par jour pour s’attabler dans un café; une seule suffit, et on peut y rester toute la journée. Au café de ce complexe d’appartements, même s’il n’y a pas de nourriture, on peut la commander auprès des vendeurs ambulants du quartier et on est servi sur place. C’est un service gratuit, typiquement vietnamien. Installés au café, nous pouvons nous détendre, lire, consulter nos téléphones, regarder le va et vient des passants et des voitures, et observer le quotidien des habitants. À peine cinq minutes après notre installation, des enfants ou des mères avec des bébés se mettaient à la queue leu leu pour nous vendre des billets de loterie. Mais comment pouvons-nous tout acheter? Chacun en avait une centaine, à 10 000 dongs le billet, et ils ne gagnaient que 1 000 dongs par billet vendu. S’ils n’arrivaient pas à tout vendre dans la journée, ils ne pouvaient pas rendre les billets à l’endroit où ils les avaient pris. Comment pouvaient-ils faire des bénéfices ? Ils allaient forcément perdre de l’argent. Il devait y avoir une astuce.

Cette façon de vendre des billets de loterie me perturbe beaucoup ; j’ai un mauvais pressentiment. Bien sûr, cela me rend un peu triste. Je donne uniquement de l’argent aux enfants qui vendent les billets mais je n’en achète pas. En revanche, mon ami n’achète des billets qu’à des personnes handicapées et les offre ensuite à ses amis âgés au Vietnam. Nous nous posons toujours des questions, mais nous n’obtenons jamais des réponses satisfaisantes. « Vivre dans le complexe d’appartements » est très difficile: l’espace est limité et les familles nombreuses sont obligées de dormir souvent par terre, si bien que « cuisiner à la maison » est une rareté. On les voit généralement traîner au bistrot, y manger ou acheter des plats à emporter. Même ma cousine vivant seule dans son appartement, préfère d’acheter souvent de quoi manger au marché.

Parfois, la bouffe achetée est incroyablement délicieuse, comme cette pâte de poisson à la vapeur avec des œufs de canard que ma cousine a achetée et agrémentée avec des légumes, ce qui nous donne un plat insatiable. J’entends souvent mon ami dire : « La génération d’aujourd’hui n’est pas celle de nos mères. Les Vietnamiennes ne savent plus cuisiner ; elles ne connaissent que Facebook ou vivre dans le monde virtuel. » Ce constat n’est pas totalement faux. Il faut bien une dose d’adrénaline pour oublier les tracas de cette vie fragile.

Au cœur de ce complexe d’appartements, on trouve de nombreux emplois lucratifs comme la couture et la cuisine, à l’instar de ceux de Mmes Mai et Lý. Mme Mai est réputée pour ses plats sautés, notamment pour son talent à leur conserver un léger goût fumé, sans les brûler, comme le riz frit au poulet et les nouilles frites croustillantes. Les plats de Mme Ly, tels que le plat de nouilles de riz agrémentées de la couenne de porc au lait de coco, le gâteau de riz à la couenne, la soupe sucrée à la banane etc. sont si délicieux que j’en ai encore l’eau à la bouche

Pour déguster ces plats, il faut s’armer de patience ; les stands de ces dames sont toujours bondés. Si on rate l’heure de fermeture, il n’y en aura plus. Ils ne proposent qu’un nombre limité de portions et, si elles sont épuisées, il faut revenir le lendemain, contrairement à Paris où de nombreux restaurants continuent à remplir leur soupe de nouilles avec de l’eau pour maintenir leur activité. Un jour, mon ami a voulu manger uniquement le porc laqué, sans les nouilles de riz, car il préférait les déguster avec du pain. Mais on a refusé de lui en vendre, car le restaurant avait déjà prévu la quantité de nouilles à vendre avec celle du porc laqué.

C’est dans ce complexe que j’ai la chance de rencontrer un jour, un jeune artiste dans un café. Il était en train de dessiner à l’encre la scène du complexe avec soin. Ce jeune artiste avait un don inné pour le dessin ; l’encre ne bavait pas. J’aimais tellement son tableau que j’aurais voulu l’acheter, mais l’artiste, si gentil, m’a dit sans hésitation: « Si tu le veux, je te le donne. » J’étais surpris. C’était le destin qui avait fait que nous nous rencontrions. Ensuite mon ami a manifesté aussi son intérêt pour l’achat d’un autre tableau pour le ramener à Paris comme cadeau offert à son ami. Je suis heureux de connaître ce jeune artiste, mais je suis aussi triste de voir souvent le petit garçon d’une douzaine d’années, qui est habitué à faire du spectacle devant la foule en crachant du feu avec de l’essence. Par hasard je l’ai interpellé un jour : « Pourquoi fais-tu ça ? Sais-tu que l’essence est toxique et que tu risques d’avoir un cancer de la gorge ? Je te conseille d’arrêter ce métier. Pris de pitié, je lui ai donné 100 000 đồng, une somme vraiment dérisoire. Je me sens impuissant car je sais que je ne peux plus rien faire pour lui.

Il y a tant de gens pauvres dans ce complexe, que puis-je faire ? Grâce à ce travail, je gagne quelques centaines de milliers de dongs par jour pour subvenir aux besoins de mon petit frère ou de ma petite sœur et vivre dignement car mes parents sont divorcés. Sa parole me hante encore lorsque j’écris encore tout ce qui est en rapport avec ce complexe d’appartements. Une seule hirondelle n’apporte pas le printemps. Mais malgré cela, je ne peux pas oublier ces enfants défavorisés. Ils sont l’avenir de notre pays.

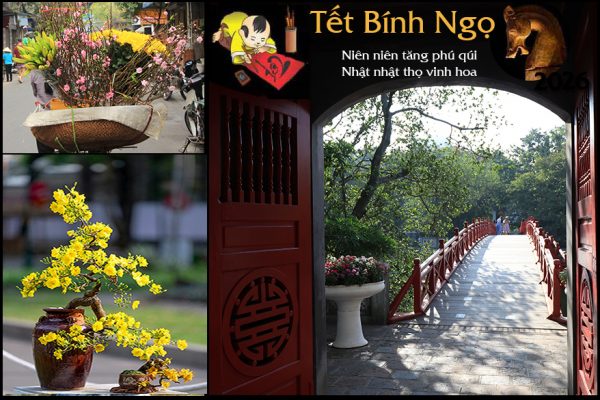

Nouvel an Bính Ngọ (17 février 2026)

Le mot «Tết» est issu du mot « tiết » qui signifie dans le dictionnaire sino-vietnamien le tronçon de bambou (ou đốt tre) au sens strict ou au sens large la période ou un espace de temps déterminé en fonction du climat dans l’année.

Au Vietnam, il existe de nombreux Tết tels que Tết Trung Thu (ou fête de la mi -automne), Tết Thanh Minh (fête des morts), Tết Đoan Ngọ (ou fête de purge) etc. mais le Tết le plus important est Tết Nguyên Đán ( 節元旦) ou Tết Cả dans la culture vietnamienne.

C’est aussi la période où les paysans laissent reposer leurs champs tout en espérant avoir de meilleures récoltes l’année prochaine grâce au renouveau de la nature nourricière. C’est pourquoi dans l’une des chansons populaires vietnamiennes on trouve les vers suivants:

Một năm là mười hai kỳ

Em ngồi em tính có gi` chẳng ra

Tháng giêng ăn Tết ở nhà

Tháng hai rỗi rãi quay ra nuôi tầm

Une année comporte douze mois

Assis, je peux les compter sans difficultés

Au premier mois je reste à la maison pour fêter le Têt

Au deuxième mois je peux commencer avec mon temps disponible, l’élevage des vers à soie.

C’est aussi la fête de l’amitié mais surtout celle du culte des ancêtres et des génies. D’après les historiens, la célébration de cette fête remonte à l’époque de la domination chinoise des Han (au premier siècle de l’ère chrétienne). La préparation de cette fête est très minutieuse et nécessite de longs jours à l’avance. Sept jours avant le Têt, il y a la cérémonie d’adieu au génie du Foyer (Ông Táo). Celui-ci revient sur terre dans la nuit du Têt au trentième jour du douzième mois lunaire. Dans le village, devant chaque maison est dressée une perche de bambou (ou Cây Nêu) pouvant atteindre plusieurs mètres.

On trouve sur cette perche des offrandes, des papiers votifs et des tablettes en argile cuite vibrant avec sonorité au gré du vent pour éloigner les esprits. C’est une vieille tradition bouddhique permettant d’interdire l’accès aux démons et aux fantômes. C’est aussi dans le village qu’on retrouve l’ambiance de fête avec les préparatifs du Têt.

Selon l’écrivain Phạm Huỳnh, le Tết est la sanctification, la glorification, l’exaltation de la religion familiale et du culte des ancêtres. C’est aussi à cette occasion que toute la famille s’est réunie du plus jeune jusqu’au plus âgé autour de la marmite pour faire cuire le gâteau de riz à la vapeur. Elle se retrouve ce jour-là au grand complet sous l’œil des ancêtres dont les tablettes sont découvertes sur l’autel nettoyé avec soin et richement décoré. La veille du nouvel an (ou đêm giao thừa), le chef de famille allume les bâtonnets d’encens sur l’autel pour inviter les âmes des ancêtres à venir passer le Têt avec les vivants.

C’est une occasion pour le chef de famille de transmettre à ses enfants la tradition du culte des ancêtres et de leur apprendre les rites du culte. Tout le monde, du plus jeune jusqu’au plus âgé se relaie pour se prosterner devant l’autel, en ayant chacun une pensée émue pour les défunts et en implorant leur aide pour la réalisation de vœux profonds. On trouve non seulement durant les jours du Têt, sur l’autel, tous les plats raffinés, des fruits triés sur le volet, des gâteaux, en particulier le gâteau de riz gluant et des tasses de thé ou d’eau mais aussi les branches de pêchers (au nord Vietnam) ou de cerisiers (au sud Vietnam) en fleurs. Celles-ci sont choisies de manière que les fleurs éclosent durant les fêtes du Têt. Des présents apportés par les enfants aux mânes des ancêtres sont aussi visibles sur l’autel pour faciliter leurs besoins dans l’autre vie. Le Têt n’est pas seulement la fête des vivants mais il est aussi la fête des morts. C’est aussi durant les trois premiers jours du Tết que ces derniers participent activement à la vie de leur famille et de leurs descendants. On les invoque aux deux principaux repas deux fois par jour. La fin du troisième jour, les mânes sont censés retourner dans l’autre monde et continuent à étendre sur les descendants les bienfaits de leur protection.

Le Tết est aussi le moment de faire revivre une vieille tradition culturelle. On voit apparaître dans des endroits publics un grand nombre de lettrés des temps modernes (ou des maîtres calligraphes). Ils sont prêts à faire des traits artistiques dans l’écriture comme le vol du dragon et la danse de phénix à l’encre de Chine sur les papiers d’un rouge vermillon étalés sur les trottoirs avec leur tour de main. Cela permet à ceux qui les leur demandent parmi les passants de pouvoir les exposer devant leur maison et de rendre cette dernière encore plus belle. De telles sentences ne manquent pas d’être visibles autour des portes des maisons ou sur les colonnes d’une pagode ou d’un temple:

Thịt mỡ dưa hành câu đối đỏ

Cây nêu tràng pháo bánh chưng xanh

Viande grasse, légumes salés, sentences parallèles rouges

Mâts du Tết, chapelets de pétards, gâteaux de riz du nouvel an.

Ou

Thiên tăng tuế nguyệt nhân tăng thọ

Xuân mãn càn khôn, phúc mãn đường

Du moment que le ciel a encore des mois et des années, vous vivez encore plus longtemps

Du moment que le printemps arrive de nouveau sur terre, votre maisonnée est inondée de nouveau de bonheur.

Ou

Niên niên tăng phú qúi

Nhật nhật thọ vinh hoa.

Que les richesses s’accumulent au fil des années

Que la gloire et le bonheur vous comblent au fil des jours.

Le Têt est aussi la fête des enfants. Ceux-ci sont parés de leurs plus beaux habits et s’amusent ensemble aux pétards dans les rues. Ils reçoivent des adultes une enveloppe rouge contenant un billet ou une pièce de monnaie qui leur porte chance durant toute l’année. Quand aux adultes, ils se rendent en procession dans les pagodes et essaient de connaître leur avenir en tirant chacun une baguette divinatoire. C’est aussi l’occasion de respecter certaines règles élémentaires que tout Vietnamien doit savoir: bannir les gros mots, mettre en sourdine toutes les querelles, ne pas toucher au balai, éviter de se présenter chez quelqu’un le premier jour de l’année etc… durant toute l’année. C’est aussi l’occasion de voir la danse de la licorne (Múa Lân) ou la danse du Dragon. Cet animal dont la tête est décorée magnifiquement et dont le corps est porté par plusieurs danseurs ondule au rythme des sons des tambourins. Il est toujours accompagné par un autre danseur hilare et ventru agitant son éventail et portant une robe de couleur safran (Ông Ðịa). C’est la danse-combat entre l’homme et l’animal, entre le Bien et le Mal qui se termine toujours par le triomphe de l’homme sur l’animal.

Les festivités du Têt se prolongent durant une semaine voire un mois dans certains villages. Mais à cause des difficultés de la vie, il est coutume de cesser de travailler seulement aujourd’hui durant les trois premiers jours de l’année.

Dans l’horoscope vietnamien, les signes astrologiques sont au nombre de douze et ils sont symbolisés par les douze animaux suivants: Rat, Buffle, Tigre, Chat, Dragon, Serpent, Cheval, Chèvre, Singe, Coq, Chien et Cochon qui se succèdent dans un ordre très précis. Contrairement à l’astrologie occidentale, le signe astrologique n’est pas déterminé en fonction du mois de naissance mais plutôt selon l’année de naissance. Chaque individu possède un signe astrologique qui est symbolisé par l’association de l’un de ces animaux trouvés dans les douze branches terrestres et l’un des cinq éléments célestes (Wu Xing)(ou Ngũ Hành en vietnamien): Thủy, Hỏa, Mộc, Kim, Thổ

Eau, Feu, Bois, Métal et Terre. Par exemple cette année est l’année du Cheval de feu (Bính Ngọ)

Le mot Bính est choisi parmi les noms des 10 troncs célestes (ou thập thiên can en vietnamien) groupés 2 par 2 à partir du Yin et Yang et de la théorie des 5 éléments (Wuxing): Giáp, Ất, Bính, Đinh, Mậu, Kĩ, Canh, Tân, Nhâm, Qúi): [Giáp, Ất] =Bois (Mộc), [Bính, Đinh]=Feu (Hỏa), [Mậu,Kĩ]=Terre (Thổ), [Canh, Tân]=Métal (Kim),[Nhâm,Quý]=Eau (Thủy)). Ce mot Bính appartient ainsi à l’élément Feu.

C’est pourquoi cette année est l’année Tết Bính Ngọ (Année du Cheval de Feu ). On ne la retrouve que tous les soixante ans (càd 1906, 1966, 2026, 2086 etc.). Dans les Annales de notre histoire, il y a eu deux Tết dont les Vietnamiens se souviennent longtemps: c’est le Têt qui permit à l’empereur Quang Trung de reconquérir notre capitale Hanoï en 1788 contre les Qing et le Tết Mậu Thân en 1968 au Sud-Vietnam.

Le Tết est pour chacun des Vietnamiens une période infiniment heureuse qui a l’avantage de se renouveler tous les ans et qui lui permet de vivre durant quelques jours dans une sorte d’allégresse et d’avoir une satisfaction malgré les aléas de la vie. Même pauvre, on a envie d’avoir une vie radieuse pour un nouvel Tết comme le célèbre poète Trần Tế Xương dans son poème intitulé: Le nouvel an (*)

Ami, ne croyez pas qu’en ce Tết je sois pauvre!

Je n’ai pas encore retiré l’argent de mon coffre

Mon vin de chrysanthème, on tarde à l’apporter;

Et le thé au lotus, le prix à débattre,

Pour les gâteaux sucrés, j’ai craint qu’ils ne coulent

À la chaleur, de même que les pâtés de porc.

Allons, tant pis, attendons l’an prochain

Amis, ne croyez pas qu’en ce Têt je sois pauvre!

Traditions entretenues à l’occasion du nouvel an vietnamien:

(*) Trích ra trong quyển sách có tựa đề : Các con cò trên cánh đồng lúa. Lê Thành Khôi. Nhà Xuất Bản Gallimard.

Extrait du livre intitulé « Aigrettes sur la rizière ». Auteur Lê Thành Khôi. Connaissances de l’Orient. Gallimard.

Vietnamese version

French version

Before talking about the Japanese tea ceremony (or chanoyu), it is desirable to mention the origin of tea. Was tea discovered by the Chinese? Probably not, because no wild tea trees are found in China. However, this primitive plant of the same family as the Chinese one (Camellia Sinensis) was found in the northeastern region of India (Assam). Then it was later detected in the wild in the border regions of China such as Tibet, Burma, Sichuan, Yunnan, Vietnam, etc. It is interesting to recall that Sichuan was the kingdom of Shu and Yunnan that of Dian, having a very intimate link with the Lo Yue tribe (the ancestors of today’s Vietnamese). Later, these regions Sichuan and Yunnan as well as Vietnam were conquered and annexed by the Chinese during the Qin and Han dynasties. One is led to conclude that the tea tree is not a product of the Chinese, but they had the merit of domesticating this tea tree so that it would have its full delicious aroma. At first, tea was used by the Chinese as a medicine but it was not adopted in any case as a beverage. Its spread to a large number of users took place during the Tang dynasty (starting from 618).

Tea later became a classic beverage widespread in Chinese society with the appearance of the book titled « The Classic of Tea » by Lu Yu (733-804), intended to teach the Chinese how to prepare tea. It is Lu Yu himself who specified in his book: « The tea plant is a precious plant found in southern China. »

The sage Confucius had the opportunity to speak about the Bai Yue people in the « Analects » to his disciples: The Bai Yue people living south of the Yangtze River have a lifestyle, language, traditions, customs, and specific food. They dedicate themselves to rice cultivation and differ from us who are accustomed to cultivating millet and wheat. They drink water from a kind of plant gathered in the forest known as « tea. » It is interesting to recall that from the Qin-Han era onwards, there existed an imperial institution composed of local scholars (the fanshi) considered magicians specialized in star rites and government recipes. Their role was to collect, each within their own territory, ritual procedures, beliefs, local medicines, systems of representations, cosmologies, myths, legends as well as local products and submit them to political authority.

It could either retain them or not and incorporate them in the form of regulations with the aim of increasing imperial power within an ethnologically very diverse nation and providing the emperor with the means for his divine vocation. This is why there were baseless Chinese legends about the tea plant, one involving Bodhidharma, the legendary founder of Chinese Zen religion, and the other involving Shen Nong, the divine Chinese farmer. To resist sleepiness during his meditation, the former cut off his eyelids and threw them to the ground. From this piece of flesh, the very first tea plant of humanity immediately sprang forth. It is certain that Zen monks were the first to use tea to resist sleep and maintain a relaxed and serene mind during their meditation. As for Shen Nong, it was by chance that while resting under the shade of a shrub (tea plant), some of its leaves fell into his bowl of hot water. From that day, he knew how to prepare tea (around 3000 BCE) in his very ancient work « Bencao Jing » dedicated to Chinese medicine. However, this book was written during the Han dynasty (25 – 225 CE). Moreover, it is known that he was buried in Changsha in the Bai Yue region. Was he really of Chinese origin? It would have been impossible for him to travel at that time if he were.

He was obviously part of the Bai Yue because his name, although written in Chinese characters, still retains a structure coming from the Yue (normally, Nong Shen should be written in Chinese characters). The Chinese place great importance on the quality of tea.

Tencha

They consider tea preparation as an art. That is why they are interested not only in selecting the highest quality teas but also in the accessories necessary for preparation (teapots, spring water, filtered or potable water, etc.) in order to achieve a specific, delicious, and light taste. As for the Japanese, tea preparation is considered a ritual because they learned about tea and its preparation from Zen monks. They elevate tea preparation as « an art of Zen living » while more or less maintaining Shinto influence. With the four fundamental principles of the way of tea: Harmony (wa), Respect (Kei), Purity (Sei), Tranquility (Jaku), the guest has the opportunity to fully free themselves while maintaining a harmonious sharing not only with nature, the accessories used in tea preparation, the place of the ceremony but also with the host and other guests. Upon crossing the threshold of the ceremony room measuring 4 tatami mats, the guest can speak more easily to anyone (who could be a monk, a noble, or even a deity) without distinguishing social class, in an egalitarian spirit.

The guest recognizes the quiddity of life, in particular the truth of their own person through respect towards everyone and everything (such as the instruments of chanoyu). Their self-love is no longer present within them, but only a kind of feeling of consideration or respect towards others remains. Their state of mind will be serene when their five senses are no longer sullied. This is the case when they contemplate a painting (kakemono) in the alcove of the room (tokonoma) or flowers in a pot (ikebana) with their eyes. They smell the pleasant aromatic scent through their nose. They hear the sound caused by water heated on a charcoal brazier. They handle the chanoyu instruments (tea scoop, chasen, tea bowl (chawan), etc.) in an orderly manner and moisten their mouth with sips of tea. Thus, all their five senses become pure. Tranquility (jaku) is the result that the tea drinker finds at the end of these three fundamental principles mentioned above, once their state of mind has found complete refuge in serenity now, whether they live amidst the crowd or not. Tranquility is interpreted as a virtue that transcends the cycle of life. It allows them to live and contemplate life in an ordinary world where their presence is no longer necessary.

The guest realizes that the way of tea is not so simple because it involves many rules to be able to drink good tea or not, but it is also an effective means of bringing tranquility to the mind to allow one to reach inner illumination in meditation.

Sen no Rikyu

For the tea master Sen no Rikyu, who had the merit of establishing the protocols for preparing tea, the way of drinking tea is very simple: boil water, then make the tea and drink it in the correct manner.

The way of tea is a sequence of events organized in a scrupulous and careful manner. This ceremony has a maximum of 4 guests and one host. They must walk through the garden of the place where the ceremony takes place. They must perform purification (wash their hands, rinse their mouth) before entering a modest cubic room usually located at the corner of the garden through a very low door. All guests must lower their heads to enter with respect and humility. In the past, to cross the threshold of this door, the samurai had to leave his sword outside the door before meeting the host. It is here that all guests can admire the interior of the room as well as the instruments for tea preparation. They can follow the protocol phases of tea preparation.

Each event carries such a particular significance that the guest recognizes at every important moment of the ceremony. It can be said that the way of tea brings harmony between the host and their guests and shortens not only the distance separating man from the sky but also that between the guests. This is why in the world of samurai, there is the following proverb: « Once, a meeting » (Ichigo, ichie) because no encounter is the same. This allows us to be like the samurai of old, in the present moment to savor and slow down each instant with our loved ones and friends.

Version française

Version vietnamienne

Galerie des photos

Before becoming the Mekong Delta of Vietnam, this territory belonged to the kingdom of Funan for seven centuries at the beginning of the Christian era. Then it was taken back and included in the Angkorian empire at the beginning of the 8th century before being ceded to the lord of the Nguyễn at the beginning of the 17th century by the Khmer kings. It is a region irrigated by a network of canals and rivers that fertilize its plains through alluvial deposits over the centuries, thus promoting orchard cultivation. The Mekong perpetually pits the native of its delta against it, much like the Nile does with its fellah in Egypt. It has succeeded in building a « southern » identity for him and granting him a culture, the one the Vietnamese commonly call « Văn hóa miệt vườn (orchard culture). » Beyond his kindness, courtesy, and hospitality, the native of this delta shows a deep attachment to nature and the environment.

With simplicity and modesty in the way of life, he places great importance on wisdom and virtue in the education of his children. This is the particular character of this son of the Mekong, that of the people of South Vietnam who were born on land steeped in Theravada Buddhism at the beginning of the Christian era and who come from the mixing of several peoples—Vietnamese, Chinese, Khmer, and Cham—over the past two centuries. It is not surprising to hear strange expressions where there is a mixture of Chinese, Khmer, and Vietnamese words.

This is the case with the following expression:

Sáng say, Chiều xỉn, Tối xà quần

to say that one is drunk in the morning, in the afternoon, and in the evening. The Vietnamese, the Chinese, and the Cambodians respectively use say, xỉn, xà quần in their language to signify the same word « drunk. » The same glass of wine can be drunk at all times of the day and shared with pleasure and brotherhood by the three peoples.

The native of the Mekong Delta easily accepts all cultures and ideas with tolerance. Despite this, he must shape this delta over the centuries with sweat, transforming a land that was until then uncultivated and sparsely populated into a land rich in citrus orchards and fruits, and especially into a rice granary. This does not contradict what the French geographer Pierre Gourou, a specialist in the rural world of Indochina, wrote in his work on the peasants of the delta (1936):

It is the most important geographical fact of the delta. They manage to shape the land of their delta through their labor.

Before becoming the Mesopotamia of Vietnam, the Mekong Delta was a vast expanse of forests, swamps, and islets. It was an apparently inhospitable environment teeming with various forms of life and wild animals (crocodiles, snakes, tigers, etc.). This is the case in the far south of Cà Mau province, where today lies the world’s second-largest mangrove forest. That is why the difficulties faced by the first Vietnamese settlers are still recounted in popular songs.

Muỗi kêu như sáo thổi

Đỉa lội như bánh canh

Cỏ mọc thành tinh

Rắn đồng biết gáy.

The buzzing of mosquitoes resembles the sound of a flute,

leeches swim on the water’s surface like noodles floating in soup,

wild grasses grow like little elves,

field snakes know how to hiss.

or

Lên rừng xỉa răng cọp, xuống bãi hốt trứng sấu

Going up the forest to pick tiger teeth, going down to the shore to collect crocodile eggs

This describes the adventure of people daring to venture perilously into the forest to face tigers and descend into the river to gather crocodile egg clutches. Despite their bravery, danger continues to lurk and sometimes sends shivers down their spines, so much so that the song of a bird or the sound of water caused by the movement of a fish, amplified by the boat’s motion, startles them in an inhospitable environment full of dangers.

During the monsoon season, in some flooded corners of the delta, they do not have the opportunity to set foot on land and must bury their loved ones by hanging the coffins in the trees while waiting for the water to recede or even in the water itself, so that nature can take its course, as recounted in the moving stories reported by the famous novelist Sơn Nam in his bestseller « Hương Rừng Cà Mau. »

Here comes the strange land

Even the bird’s call is fearful, even the fish’s movement is scary.

It is here that, day and night, the swarm of hungry mosquitoes is visible in the sky. That is why it is customary to say in a popular song:

Tới đây xứ sở lạ lùng

Con chim kêu cũng sợ, con cá vùng cũng ghê.

Cà Mau is a rustic land,

mosquitoes as big as hens, tigers as big as buffaloes.

Cà Mau is a rural region. The mosquitoes are as large as hens and the tigers are comparable to buffaloes.

Courage and tenacity are among the qualities of these delta natives as they strive to find a better life in an ungrateful environment. The great Vĩnh Tế canal, more than 100 km long, dating back to the early 19th century, bears witness to a colossal project that the ancestors of these delta natives managed to accomplish over five years (1819-1824) to desalinate the land and connect the Bassac branch of the Mekong (Châu Ðốc) to the Hà Tiên estuary (Gulf of Siam) under the direction of Governor Thoại Ngọc Hầu. More than 70,000 Vietnamese, Cham, and Khmer subjects were mobilized and forcibly enlisted in this endeavor. Many people had to perish there.

On one of the 9 dynastic urns arranged in front of the temple for the worship of the kings of the Nguyễn dynasty (Thế Miếu) in Huế, there is an inscription recounting the excavation work of the Vĩnh Tế canal with gratitude from Emperor Minh Mạng to the ancestors of the natives of the Mekong. Vĩnh Tế is the name of Thoại Ngọc Hầu’s wife, whom Emperor Minh Mạng chose to recognize her merit for courageously helping her husband in the construction of this canal. She passed away two years before the completion of this work.

The delta was at one time the starting point for the exodus of boat people after the fall of the Saigon government (1975). Some perished on the journey without any knowledge of navigation. Others who failed to leave were captured by the communist authorities and sent to re-education camps. The harshness of life does not prevent the natives of the Mekong from being happy in their environment. They continue to maintain their hospitality and hope to one day find a better life. Over the centuries, they have forged an unparalleled determination and community spirit in search of fertile land and a space of freedom. Speaking of these people of the delta, one can recall the phrase of the writer Sơn Nam at the end of his book titled « Tiếp Cận với đồng bằng sông Cửu Long » (In Contact with the Mekong Delta): No one loves this delta more than we do. We accept paying the price for it.

It is in this delta that one finds today all the charming facets of the Mekong (the sun, the smile, the exoticism, the hospitality, the conical hat silhouettes, the sampans, the floating markets, the stilt houses, an abundant variety of tropical fruits, cage fish farming, floating rice, local specialties, etc.). This is reflected in the following proverb:

Ðất cũ đãi người mới

The old land welcomes the newcomers.

At the time of the country’s reunification in 1975, the Vietnamese government settled more than 500,000 farmers from the North and Central Vietnam in the labyrinth of this delta. Fed by rich alluvium, it is highly fertile. Today, it has become the economic lung of the country and a boon for the 18 million people in the region. It is said that it alone could feed all of Vietnam.

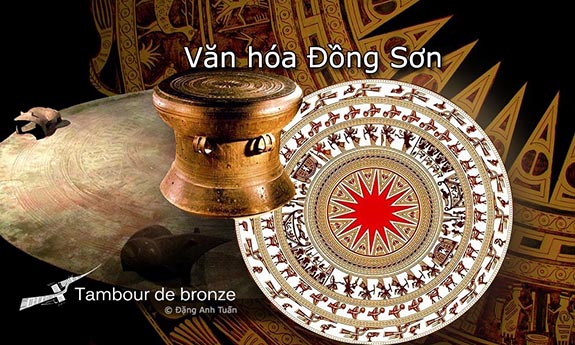

Who are the Dongsonians?

Version française

Version vietnamienne

It is very important to know them because we know they were the owners of these bronze drums. Are they the ancestors of the current Vietnamese? Very little is known about these people and their culture because the research started in the early 20th century by the French was interrupted during the long years of war that Vietnam experienced. However, it is certain that in the 1st century AD, the Dongsonian culture ended with the Chinese annexation.

It was only from 1980 that archaeological excavations resumed. We began to better understand their origin, way of life, and sphere of influence. Thanks to the exceptionally enriched archaeological documentation in recent years, the origin of the Dongsonian culture has been fairly clarified. This culture has its roots among the pre-Dongsonian cultures (those of Phùng Nguyên, Ðồng Dậu, and Gò Mun). There is no need to look so far north or west for the origin of this culture. The Dongsonian culture is actually the result of a succession of stages corresponding to these three cultures mentioned above in a continuous cultural development. The eminent Vietnamese archaeologist Hà Văn Tấn was right to solemnly say: To search for the origins of the Dongsonian culture in the North or West, as several researchers did in the past, is to put forward a hypothesis without scientific basis.

Thanks to the distribution maps of archaeological sites in the Red River basin, it is evident that the pre-Dongson Bronze Age cultures occupied exactly the same region where the sites of the Phùng Nguyên culture were located. It can be said without hesitation that the Đông Sơn culture extends from Hoàng Liên Sơn province in the north to Bình Trị Thiên province in the south.

The Dongsonians were above all skilled rice farmers. They cultivated rice using slash-and-burn methods and flooded fields. They raised buffaloes and pigs. But it was water that was both their wealth and their primary concern because it could be deadly, overflowing from the Red River to engulf crops. They were daring navigators, so close to rivers and coasts that they were accustomed to using dugout canoes for their movements. This custom was so deeply ingrained in their minds that they built their homes as wooden stilt houses with immense roofs curved at both ends, decorated with totemic birds and resembling a dugout canoe.

Even in their death, they designed coffins shaped like canoes. According to Trịnh Cao Tường, a specialist in the study of communal houses (đình) of Vietnamese villages, the architecture of the Vietnamese communal house elevated on stilts reflects the echo of the spirit of the Dongsonians still present in the daily life of the Vietnamese.

The Dongsonians used to tattoo their bodies, chew a preparation made from areca nuts, and blacken their teeth. Tattooing, often described as a « barbaric » practice in Chinese annals, was, according to Vietnamese texts, intended to protect people from attacks by water dragons (con thuồng luồng).

The habit of chewing betel is very ancient in Vietnam. It existed long before the Chinese conquest. When mentioning the blackening of teeth, one cannot forget the famous phrase spoken by Emperor Quang Trung before the liberation of the capital « Thăng Long, » occupied by the Qing: « Đánh để được giữ răng đen. » Fight the Chinese to liberate the city and to keep the teeth blackened. This clearly shows his political will to perpetuate Vietnamese culture, particularly that of the Dongsonians.

They wore their hair long in a bun and supported by a turban. According to some Vietnamese texts, they had short hair to facilitate their movement in the mountain forests. Their clothing was made from plant fibers. During recent excavations of the Làng Cả necropolis (Việt Trì) in 1977 and 1978, it was observed that differences in wealth were pronounced among the Dongsonians in the analysis of funerary furniture. Opulence is visible in certain individual tombs. Society began to structure itself in a way that revealed the gap between the rich and the poor through funerary furniture. There is no longer any doubt about the increasingly advanced hierarchy in Dongsonian society. It is also found in their military hierarchy: the wearing of metal armor was reserved for the great military chiefs. Lesser chiefs had to make do with leather cuirasses or tree bark coats of armor, similar to those of the Dayak in Borneo, Indonesia.

During recent archaeological excavations, Vietnamese archaeologists are confronted with the burial practices used by the Dongsonians. They employed various modes of burial: interments in pits (mộ huyện đất) with the deceased in a lying or crouching position (Thiệu Dương), burials in dugout coffin boats (mộ thuyền) (Việt Khê, Châu Can, Châu Sơn), burials in bronze jars or inverted drums (mộ vò). ( Đào Thịnh, Vạn Thắng) .

The burial mode in boat-shaped coffins has only been found in certain regions of Northern Vietnam (Hải Phòng, Hải Hưng, Thái Bình, Hà Nam Ninh, and Hà Sơn Bình). The area is very limited compared to the zone of influence of the Đồng Sơn culture. On the other hand, in famous Dong Son sites such as Làng Cả (Vĩnh Phú), Đồng Sơn, Thịệu Dương (Thanh Hoá), Làng Vạc (Nghệ Tĩnh), no burial mode involving boat-shaped coffins has been reported. Some Vietnamese archaeologists like Hà Văn Tấn believe that the coffins had the possibility of being preserved because they were located in a marshy area. This is not the case for other coffins, as they were situated in unfavorable places where water could erase everything over time.

According to Vietnamese archaeologist Hà Văn Tấn, the marsh area could have been, during the Dong Son period, a swampy region where people lived under conditions similar to those who habitually soaked their skin and skeleton in water throughout their lives and in death. (Sống ngâm da, chết ngâm xương). It is not surprising to find in these people their way of thinking and their method of burying the dead in boat-shaped coffins because for them, from birth to death, the means of transport was always the boat.

Other archaeologists question the disappearance of this custom among the Vietnamese. Why does this burial method continue to be practiced by the Mường, close cousins of today’s Vietnamese? Yet they share the same ancestors. The explanation that can be given is as follows: the diversity of burials clearly shows the « disparate » nature among the Dongsonians. Considered as Indonesians (or Austroasians (Nam Á in Vietnamese)), they are in fact populations of the same culture but remain physically heterogeneous. According to Russian researchers Levin and Cheboksarov, the Indonesians would be a mix of Australoids and Mongoloids. They originated from the fusion of the Luo Yue (Lac Việt), (Australo-Melanesian elements, ancient inhabitants of eastern Indochina who still remained on the continent) and Mongoloid elements probably coming via the Blue River from the borders of Tibet and Yunnan during the Spring and Autumn period (Xuân Thu). It does not appear that physical diversity is accompanied by cultural diversity. At each era, the same tools and customs seem common to all. If there is a difference in the burial method, this can be explained by the lack of resources and forced Sinicization among the Vietnamese. This is not the case for the Mường, who, taking refuge in the most remote corners of the mountains, can perpetuate this custom without any difficulty.

According to archaeologist Hà Văn Tấn, it is possible to find oneself in this hypothesis illustrated by the example of the burial method, which is carried out differently today among the Southern Vietnamese (descendants of a mixture of Vietnamese, Chinese, Chams, and Khmers) and those from the North, even though they come from the same people and the same culture.

It is through picturesque traits that we begin to better understand the Dongsonians during archaeological excavations. There is no longer any doubt about their origin. They belonged to the Hundred Yue or Bai Yue because in them we find everything related to the Bai Yue: tattooing, teeth lacquering, betel chewing, worship of totem animals, stilt houses, use of drums, etc., among the 25 characteristic elements found among the Yue and cited by the British sinologist Joseph Needham. They were designated in Chinese annals by different generic names: Man Di during the Spring and Autumn period, Hundred Yue (or Bai Yue) during the Warring States period (Tam Quôc), Kiao Tche (or Giao Chi in Vietnamese) during the Han (or Chinese) domination.

According to Vietnamese scholar Đào Duy Anh, the name Kiao Tche (Giao Chỉ) given to the Yue peoples in northern Vietnam originally designates the territories occupied by the Yue who worship the kiao long (giao long) (crocodile-dragon), kiao and tche meaning respectively dragon and territory.

This hypothesis was adopted and supported by Vietnamese archaeologists Hà Văn Tấn and Trần Quốc Vượng. This crocodile-dragon, a totemic animal of the Dongsonians, is found in funerary artifacts: axes, spears, armor plates, and thạp vases (for example, Đào Thịnh). It is from this multiple mixture of Dongsonians with other ethnic groups from Si Ngeou (Tây Âu), ancestors of the Tày, Nùng, Choang, and close relatives of the Thai in the mountainous regions of Kouang Si (Guangxi) and Northern Vietnam at the beginning of the Iron Age (3rd century BC, Âu Lạc period) that today’s Vietnamese originate.

The territory of the Hundred Yue is so vast that it forms an inverted triangle with the Yangtze River (Dương Tử Giang) as the base, Tonkin (Northern Vietnam) as the apex, the regions of Tcho-Kiang (Zhejiang), Fou Kien (Fujian), and Kouang-Tong (Guangdong) on its eastern side, and the regions of Sseu-tchouan (Sichuan), Yunnan (Vân Nam), Kouang Si (Guangxi) on its western side. (Paul Pozner).

Many chiefdoms were established there, and there were no borders hindering the spread and circulation of their traditions, particularly the making and use of bronze drums. This is why it is possible that bronze drums were made at the same time in distinct centers within the territories of the Yue (Vietnam, Yunnan, Guangxi) according to different casting techniques (lost-wax casting in Vietnam, mold sections in Yunnan) and according to the availability of local mining resources.

In the analyses of Ðồng Sơn bronzes, it is observed that the percentage of lead is higher than that of tin, which is an exceptional fact in the technology of Dong Son bronze. But it is surprising to find roughly the same lead and tin content in the analysis of the Kur drum bronze in Indonesia. It would have been impossible for the Indonesians of that time to chemically analyze this drum to know the content of each metal. They must have learned from the Dong Son people either directly or indirectly. This strongly supports the hypothesis of the diffusion of metallurgy from the Red River basin starting in Vietnam, unless Dong Son metallurgists were present on their territory at that time.

Moreover, the Dong Son people knew how to seek an appropriate alloy for each type of object they made. This is the case with the weapons found in the Dong Son burial sites, where the lead content is lower and the tin content quite significant, giving them a remarkable degree of hardness. Furthermore, the percentages of metals in the chemical composition of the bronzes from Jinning (Yunnan) are roughly the same as those of ancient Chinese bronzes. (Nguyễn Phước Long: 107). This is not the case with the Dong Son bronzes.

These were local and original products and belonged to the Red River civilization. Living on the edge of the East Sea or South China Sea (Biển Đông), the Dong Son people were close to major trade routes, which allowed for a wide dissemination of their culture and their bronze drums. It was about 2 km from the Vietnamese coast in the Vũng Áng region (Hà Tĩnh) that a Vietnamese fisherman accidentally caught two objects in his net in 2009 in the East Sea: a bronze axe and a spearhead dating from the Đồng Sơn period.

This proves that the Dongsonian people used maritime routes to establish a network of exchanges with all the states bordering the South China Sea (starting from the north, clockwise). In Zhejiang (Triết Giang), during an archaeological excavation at Thượng Mã Sơn (An Cát, Hồ Châu or Huzhou Shi), Chinese archaeologists found an object that was not native to this region and undoubtedly belonged to the Dongsonian civilization. It is a bronze drum similar to the one found in Lãng Ngâm in Bắc Ninh province in Northern Vietnam. (Trịnh Sinh 1997). Then in Canton, in the tomb of King Zhao Mei (Triệu Muội), identified as the second ruler of Nan Yue and known as Nam Việt Vương in Vietnamese, cylindrical situlas with geometric decoration (thạp) were discovered, frequently found in Dongsonian sites in Vietnam. Finally, along the Vietnamese coast (Champa, Chenla), in territories where the Sa Huỳnh culture was present at that time, bronze drums, daggers, and Dongsonian axes were also found in bronze jar burials (mộ vò).

Further inland, on the island (Hòn Rái) of Kiên Giang province, near Phú Quốc island, in the Gulf of Siam, a Đông Sơn bronze drum was discovered in 1984 during the exhumation of bodies, inside which were found axes, spearheads, as well as human bones. We must also not forget the bronze drums found in Thailand, characterized by the three elements copper, lead, and tin, with lead content reaching up to 20% (U. Gueler 1944), which testifies to one of the characteristics of Đông Sơn bronzes (Trinh Sinh: 1989: 43-50). The Đông Sơn civilization developed in a very open environment. In northern Vietnam, the flow of information and objects was facilitated by the Red River, which originates in Yunnan and was considered the river Silk Road between the Dian kingdom and that of the Đông Sơn people. Benefiting from the abundance of mineral deposits in their territory and the proximity to the coasts of the East Sea, they succeeded in developing a spectacular bronze art and imposing a very original and distinctive style through their bronze drums, situlas, and magnificent objects, which probably explains their leadership role in mastering lost-wax casting and facilitating exchanges not only within the Yue territories but also in territories as distant as those.

For the Dongsonians as for the Yue, the bronze drum was not only a common cult heritage that they were supposed to keep carefully but also an emblem of power and rallying beyond their village and ethnic community. The bronze drum, which guaranteed agrarian rites and social cohesion, was made by talented local metallurgists solely to perpetuate their ancestral tradition, never considering that their artistic work could become an object of dispute between the two peoples, Vietnamese and Chinese, one being considered the legitimate heir of the Hundred Yue and supposed to revive the civilization of its ancestors, that of the Bai Yue, and the other, conqueror of the territories of the Bai Yue and supposed to restore to the descendants of the Yue the place they deserve in today’s China. One cannot remain indifferent to the hypothesis defended by the sinologist Charles Higham in his work entitled « The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia« :

The search for origins and changes occurring in the second half of the 1st millennium BCE in the region leads to the overlooking of an important point. These changes taking place in what have become today the south of China and the Red River Delta basin were accomplished by groups exchanging their ideas and goods in response to strong pressure from the north, from powerful and expansionist states (Chu (Sỡ), the Qin (Tần), and the Han (Hán)) who ultimately managed to crush them.

From a historical and cultural perspective, all those descended from the Yue have the right to claim this heritage. But from a logical standpoint, only the Luo Yue (or the Dongsonians) among the Baiyue succeeded in forming a nation and having an autonomous and independent country (Vietnam). This is not the case for the other Yue, who were all sinicized over the centuries during the imperial expansion initiated by the Qin and the Han. No one has the right to contest the Yue character in present-day Vietnamese. This is also the observation made by the French ethnologist Georges Condominas:

Mentioning the Yue is to go back to the origins of Vietnamese identity. (G. Condominas). It is obvious that the paternity of the bronze drums belongs to the Vietnamese, especially since these sacred instruments could carry a message left to them by their ancestors (the Dongsonian people). The inscription engraved on the bronze column of General Ma Yuan is well known: Let this column fall and Giao Chỉ will disappear (Ðồng trụ triệt, Giao Chỉ diệt). Where is this bronze column when we know that Giao Chi (Vietnam) continues to exist today? By closely observing a bronze drum, one notices that it resembles a cut tree trunk. Its tympanum bearing several concentric circles is analogous to the cross-section of the trunk with rings added over the centuries.

Does the bronze drum evoke Ma Yuan’s bronze column? Some scientists believe that the bronze drum is the « tree of life. » This is the case for the Russian scientist N.J. Nikulin from the Moscow Institute of Culture. Relying on the discoveries and suggestions of Vietnamese researchers (such as Lê Văn Lan) about the idea of a « totality » represented by the bronze drum through its depictions, he arrives at the following conclusion: The bronze drum is a representation of the universe: the tympanum (or the plate), symbolizing the celestial and terrestrial world (thiên giới, trần giới), the trunk representing the marine world (thủy quốc), and the base representing the underground world (âm phủ). According to him, there is an intimate relationship between the bronze drum and the mythical narrative of the Mường, close relatives of the present-day Vietnamese.

In the Mường conception of the creation of the universe, the tree of life symbolizes the notion of universal order, as opposed to the chaotic state found at the moment of the world’s creation. The worship of the tree is a very ancient custom of the Vietnamese. The areca palm found in the betel quid (chuyện trầu cau) testifies to this worship. According to historian and archaeologist Bernet Kempers, the bronze drum illustrates a fundamentally monistic (Oneness) vision of the cosmos.

It is this bronze drum that the Han wanted to destroy to seal the fate of the Dongsonians because it was the tree of life symbolizing both their strength and their conception of life. Fortunately, over the centuries, the bronze drum did not disappear, but thanks to the picks and shovels of French and Vietnamese archaeologists, it reappeared splendid and radiant, allowing the descendants of the Dongsonians to rediscover their true history, their origin without being seen as cooked barbarians.

Being a sacred instrument, the bronze drum is more than ever involved in the restoration and testimony of the identity of the Vietnamese people, which was nearly erased many times by the Middle Kingdom throughout its history.

Until today, the bronze drums continue to sow discord between the Vietnamese and Chinese scientific communities. For the Vietnamese, the bronze drums are the prodigious and ingenious invention of peasant metallurgists during the time of the Hùng kings, the founding fathers of the Văn Lang kingdom. It was in the Red River delta that the French archaeologist Louis Pajot unearthed several of these drums at Ðồng Sơn (Thanh Hoá province) in 1924, along with other remarkable objects (figurines, ceremonial daggers, axes, ornaments, etc.), thus providing evidence of a highly sophisticated bronze metallurgy and a culture dating back at least 600 years before Christ. The Vietnamese find not only their origin in this re-excavated culture (or Đông Sơn culture) but also the pride of reconnecting with the thread of their history. For the French researcher Jacques Népote, these drums become the national reference of the Vietnamese people. For the Chinese, the bronze drums were invented by the Pu/Liao (Bộc Việt), a Yue ethnic minority from Yunnan (Vân Nam). It is evident that the authorship of this invention belongs to them, aiming to demonstrate the success of the process of mixing and cultural exchange among the ethnic groups of China and to give China the opportunity to create and showcase the fascinating multi-ethnic culture of the Chinese nation.

Despite this bone of contention, the Vietnamese and the Chinese unanimously acknowledge that the area where the first bronze drums were invented encompasses only southern China and northern present-day Vietnam, although a large number of bronze drums have been continuously discovered across a wide geographical area including Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Indonesia, and the eastern Sunda Islands. Despite their dispersion and distribution over a very vast territory, fundamental cultural affinities are noted among populations that at first glance appear very different, some protohistoric and others almost contemporary. Initially, in the Chinese province of Yunnan where the Red River originates, the bronze drum has been attested since the 6th century BCE and continued to be used until the 1st century, just before the annexation of the Dian kingdom (Điền Quốc) by the Han (or Chinese). The bronze chests intended to contain local currency (or cowries), discovered at Shizhaishan (Jinning) and bearing on their upper part a multitude of figures or animals in sacrificial scenes, clearly testify to the indisputable affinities between the Dian kingdom and the Dongsonian culture.

Then among the populations of the Highlands (the Joraï, the Bahnar, or the Hodrung) in Vietnam, the drum cult is found at a recent date. Kept in the communal house built on stilts, the drum is taken down only to call the men to the buffalo sacrifice and funeral ceremonies. The eminent French anthropologist Yves Goudineau described and reported the sacrificial ceremony during his multiple observations among the Kantou of the Annamite Trường Sơn mountain range, a ceremony involving bronze drums (or Lakham) believed to ensure the circularity and progression of the rounds necessary for a cosmogonic refoundation.

These sacred instruments are perceived by the Kantou villagers as the legacy of a transcendence. The presence of these drums is also visible among the Karen of Burma. Finally, further from Vietnam, on the island of Alor (Eastern Sunda), the drum is used as an emblem of power and rank, as currency, as a wedding gift, etc. Here, the drum is known as the « mokko. » Its role is close to that of the bronze drums of Ðồng Sơn. Its prototype remains the famous « Moon of Pedjeng » (Bali), whose geometric decoration is close to the Dong Son tradition. This one is gigantic and nearly 2 meters high.

More than 65 citadels spread across the territories of the Bai Yue responded favorably to the call of the uprising led by the Vietnamese heroines Trưng Trắc and Trưng Nhị. Perhaps this is why, under Chinese domination, the Yue (which included the proto-Vietnamese or the Giao Chi) hid and buried all the bronze drums in the ground for fear of them being confiscated and destroyed by the radical method of Ma Yuan. This could explain the reason for the burial and location of a large number of bronze drums in the territory of the Bai Yue (Bách Việt) (Guangxi (Quảng Tây), Guangdong (Quảng Đông), Hunan (Hồ Nam), Yunnan (Vân Nam), Northern Vietnam (Bắc Bộ Vietnam)) during the conquest of the Qin and Han dynasties. The issuance of the edict by Empress Kao (Lữ Hậu) in 179 BC, stipulating that it was forbidden to deliver plowing instruments to the Yue, is not unrelated to the Yue’s reluctance towards forced assimilation by the Chinese.

In Chinese annals, bronze drums were mentioned with contempt because they belonged to southern barbarians (the Man Di or the Bai Yue). It was only from the Ming dynasty that the Chinese began to speak of them in a less arrogant tone after the Chinese ambassador Trần Lương Trung of the Yuan dynasty (or Mongols (Nguyên triều)) mentioned the drum in his poem entitled « Cảm sự (Resentment) » during his visit to Vietnam under the reign of King Trần Nhân Tôn (1291).

Bóng lòe gươm sắc lòng thêm đắng

Tiếng rộn trống đồng tóc đốm hoa.

The shimmering shadow of the sharp sword makes us more bitter

The tumultuous sound of the bronze drum makes our hair speckled with white.

He was frightened when he thought about the war started by the Vietnamese against the Mongols to the sound of their drum.

On the other hand, in Chinese poems, it is never recognized that the bronze drums are part of the cultural heritage of the Han. It is considered perfectly normal that they are the product of the people of the South (the Yue or the Man). This fact is not doubted many times in Chinese poems, some lines of which are excerpted below:

Ngõa bôi lưu hải khách

Ðồng cổ trại giang thần

Chén sành lưu khách biển

Trống đồng tế thần sông

The earthenware bowl holds back the traveling sailor,

The bronze drum announces the offering to the river spirit.

in the poem « Tiễn khách về Nam (Accompanying the traveler to the South) » by Hứa Hồn.

Thử dạ khả liên giang thượng nguyệt

Di ca đồng cổ bất thăng sầu !

Ðêm nay trăng sáng trên sông

Trống đồng hát rơ cho lòng buồn thương

or

The moon of this night shimmers on the river

The barbarians’ song to the sound of the drum arouses painful regrets.

in the poem titled « Thành Hà văn dĩ ca » by the famous Chinese poet of the Tang dynasty, Trần Vũ.

In 1924, a villager from Ðồng Sơn (Thanh Hoá) recovered a large number of objects including bronze drums after the soil was eroded by the flow of the Mã river. He sold them to the archaeologist Louis Pajot, who did not hesitate to report this fact to the French School of the Far East (École Française d’Extrême-Orient). They later asked him to be responsible for all excavation work at the Ðồng Sơn site.

But it was in Phủ Lý that the first drum was discovered in 1902. Other identical drums were acquired in 1903 at the Long Ðội Sơn bonzerie and in the village of Ngọc Lữ (Hà Nam province) by the French School of the Far East. During these archaeological excavations begun in 1924 around the Ðồng Sơn hill, it was realized that a strange culture with canoe-tombs was being uncovered.

These are actually boats made from a single piece of wood, sometimes reaching up to 4.5 meters in length, each containing a deceased person surrounded by a whole set of funerary furniture: ornaments, halberds, parade daggers, axes, containers (situlas, vases, tripods), pottery, and musical instruments (bells, small bells). Moreover, in this funerary skiff are objects of quite large dimensions and recognizable: bronze drums, some measuring more than 90 cm in diameter and one meter in height. Their shape is generally very simple: a cylindrical box with a single slightly flared bottom forming the upper part of the drum. On this sounding surface, there is at its center a multi-pointed star which is struck with a mallet. Four double handles are attached to the body and the middle part of the drum to facilitate suspension or transport using metal chains or plant fiber ropes. These drums were cast using a clay mold, into which a bronze and lead alloy was poured.

The Austrian archaeologist Heine-Geldern was the first to propose the name of the Đồng Sơn site for this re-excavated culture. Since then, this culture has been known as « Dongsonian. » However, it is to the Austrian scholar Franz Heger that much credit is due for the classification of these drums. Based on 165 drums obtained through purchases, gifts, or accidental discoveries among bronze workers or ethnic minorities, he managed to accomplish a remarkable classification work that still has a significant influence in the global scientific community today, serving as an essential reference for the study of bronze drums. His work was compiled into two volumes (Alte Metaltrommeln aus Südostasien) published in Leipzig in 1902.

Version française

Version anglaise

Chúng ta tự gọi là « Thầy » vì chính tại đây, nhà sư Từ Đạo Hạnh đã sáng tạo và truyền dạy cho người dân địa phương một loại hình nghệ thuật độc đáo: múa rối nước. Ngoài ra còn có chùa Côn Sơn nằm trên ngọn núi cùng tên, cách Hànội 60km, thuộc tỉnh Hải Dương. Chùa gồm khoảng hai mươi tòa nhà, ẩn mình trong rừng thông, trên đỉnh một cầu thang dài vài trăm bậc. Chính tại đây, sau khi từ giã sự nghiệp chính trị, nhà nhân văn nổi tiếng Nguyễn Trãi đã để lại cho chúng ta một bài thơ khó quên mang tên « Côn Sơn Ca« , trong đó ông mô tả cảnh quan hùng vĩ của ngọn núi này và cố gắng tóm tắt cuộc đời của một người chỉ có thể sống tối đa một trăm năm và người mà mọi người đều tìm kiếm những gì mình mong muốn trước khi cuối cùng trở về với cỏ và bụi. Nhưng ngôi chùa được viếng thăm nhiều nhất vẫn là Chùa Hương. Trên thực tế, đây là một quần thể các công trình được xây dựng trên vách núi.

Nằm cách thủ đô 60 km về phía tây nam, đây là một trong những thánh địa quốc gia được hầu hết người Việt Nam lui tới, cùng với chùa Bà Chúa Xứ (Châu Đốc) gần biên giới Campuchia vào dịp Tết. Ở miền Trung Việt Nam, Chùa Thiên Mụ, nằm đối diện sông Hương, không hề kém phần quyến rũ, trong khi ở phía nam, tại tỉnh Tây Ninh, không xa Sài Gòn, nằm nép mình trên núi Bà Đen (núi Bà Đen), một ngôi chùa cùng tên.

Chỉ riêng tại thủ đô Hà Nội, đã có ít nhất 130 ngôi chùa ở khu vực lân cận. Số lượng chùa cũng nhiều như số làng. Thật khó để liệt kê hết. Tuy nhiên, do sự biến đổi của thời gian và sự tàn phá của chiến tranh, chỉ còn một số ít công trình vẫn giữ được nguyên vẹn phong cách kiến trúc và điêu khắc có từ thời Lý, Trần và Lê.

Đôi khi sự tàn phá của con người là nguyên nhân dẫn đến sự phá hủy một số ngôi chùa nổi tiếng. Đây là trường hợp của chùa Báo Thiên, nơi mà địa điểm đã được nhượng lại cho chính quyền thực dân Pháp để xây dựng nhà thờ Thánh Giuse theo phong cách tân Gothic mà ngày nay có thể được nhìn thấy ở trung tâm thủ đô, không xa Hồ Hoàn Kiếm nổi tiếng (Hà Nội). Nhìn chung, hầu hết các ngôi chùa ngày nay vẫn còn lưu giữ rõ ràng dấu vết của việc trùng tu và tôn tạo dưới thời nhà Nguyễn. Mặt khác, các đồ vật tôn giáo, tượng đá và đồng của họ ít bị thay đổi và vẫn giữ được trạng thái ban đầu qua nhiều thế kỷ. Hơn nữa, khi chúng ta di chuyển vào miền Trung và miền Nam Việt Nam, chúng ta nhận thấy rằng ảnh hưởng của Chăm và Khmer không vắng mặt trong kiến trúc của các ngôi chùa vì những lãnh thổ này trong quá khứ lần lượt thuộc về các vương quốc Champa và Funan.Mặc dù số lượng chùa chiền rất nhiều và quy mô đa dạng, nhưng cách sắp xếp các công trình kiến trúc của chúng vẫn không thay đổi. Điều này dễ dàng nhận ra qua 6 chữ Hán nổi tiếng sau: Nhất, Nhị, Tam, Đinh, Công và Quốc (hay 一, 二, 三, 丁, 工 và 国 trong tiếng Trung). Sự đơn giản thể hiện rõ qua mẫu hình được xác định bởi chữ đầu tiên Nhất, trong đó các công trình kiến trúc nối tiếp nhau thành một hàng ngang duy nhất hướng ra hiên nhà (Tam Quan).

Đây là hình ảnh thường thấy ở hầu hết các ngôi chùa ở các làng quê không có trợ cấp nhà nước hoặc ở Đồng bằng sông Cửu Long ở miền Nam Việt Nam. Chữ thứ hai Nhị có nghĩa là « hai » gợi nhớ đến cách sắp xếp hai hàng ngang song song hướng ra hiên nhà. Ngôi chùa này có ưu điểm là có ít nhất ba cửa phụ và dẫn vào một khoảng sân nơi thảm thực vật tươi tốt và hiện diện khắp nơi nhờ những bụi cây rậm rạp và hoa trồng trong chậu. Đôi khi chúng ta thấy mình đang ở giữa một ao sen và súng, không khỏi gợi nhớ đến sự thanh bình hòa hợp với thiên nhiên. Với chữ Tam thứ ba, có ba hàng ngang song song thường được nối với nhau ở giữa bằng những cây cầu nhỏ hoặc một hành lang. Đây là trường hợp của chùa Kim Liên (Hà Nội) và chùa Tây Phương (Hà Tây). Hàng đầu tiên tương ứng với một nhóm các tòa nhà, tòa nhà đầu tiên thường được gọi là « tiền đường ». Đôi khi được gọi bằng tên tiếng Việt là « bái đường », tòa nhà này được sử dụng để tiếp đón tất cả các tín đồ. Nó được bảo vệ tại lối vào bởi các vị thần hộ mệnh (hoặc dvàrapalàs hoặc hộ pháp), những người, với những nét mặt đe dọa, mặc áo giáp và trưng bày vũ khí của họ (giáo, mũ sắt, v.v.). Đôi khi, mười vị vua của địa ngục (Thập điện diêm vương hoặc Yamas) ngồi trên ngai vàng bên cạnh phòng trước này, hoặc 18 vị La Hán (Phật La Hán) trong các tư thế khác nhau của họ trong hành lang. Đây là trường hợp của chùa (Chùa Keo), nơi 18 vị La Hán hiện diện trong phòng trước. Đôi khi còn có thần đất hoặc thần bảo vệ tài sản của chùa (Đức Ông).

Một trong những đặc điểm của chùa Việt Nam là sự hiện diện của mẫu thần Mẫu Hạnh (Liễu Hạnh Công Chúa), một trong bốn vị thần được người Việt Nam thờ phụng. Sự tôn kính của bà có thể thấy rõ ở gian trước của chùa Mía (Chùa Mía, Hà Tây). Sau đó, trong một tòa nhà thứ hai cao hơn một chút so với tòa nhà thứ nhất, có những lư hương cũng như tấm bia đá kể lại câu chuyện về ngôi chùa. Đây là lý do tại sao nó được gọi là « nhà thiêu hương ». Cũng ở phía sau của tòa nhà này có một bàn thờ, phía trước có các nhà sư tụng kinh cùng các tín đồ bằng cách đánh một chiếc chuông gỗ (mõ) và một chiếc chuông đồng úp ngược (chông). Đôi khi có thể tìm thấy chuông trong nhóm các tòa nhà này nếu vị trí của tháp chuông (gác chuông) không được quy hoạch bên cạnh (hoặc trên sàn) hiên nhà. Bất kể kích thước của ngôi chùa, phải có ít nhất ba tòa nhà cho hàng đầu tiên này.Sau đó, chúng ta thấy hàng quan trọng nhất của ngôi chùa tương ứng với phòng của các bàn thờ chính (thượng điện). Đây là nơi chúng ta có đền thờ phong phú và có thứ bậc. Nó được phân bổ trên ba bệ. Trên bệ cao nhất dựa vào bức tường phía sau, chúng ta thấy bàn thờ của các vị Phật của Ba Thời Đại (Tam Thế). Trên bàn thờ này, trong khái niệm Phật giáo Màhayàna (Phật Giáo Đại Thừa), xuất hiện ba bức tượng đại diện cho Quá khứ (Quá Khứ), Hiện tại (Hiện tại) và Tương lai (Vị Lai), mỗi bức tượng ngồi trên một tòa sen.

Trên bệ thứ hai, được đặt thấp hơn bệ thứ nhất một chút, là ba bức tượng được gọi là ba hiện hữu, với Đức Phật A Di Đà (Phật A Di Đà) ở giữa, Bồ Tát Quán Thế Âm ở bên trái (Bồ Tát Quan Âm) và Bồ Tát Đại Thế Chí ở bên phải (Bồ Tát Đại Thế Chí). Nhìn chung, Đức Phật A Di Đà có vóc dáng uy nghi hơn hai vị kia. Sự hiện diện của Ngài chứng minh tầm quan trọng của người Việt đối với sự tồn tại của Tịnh Độ trong Phật giáo. Niềm tin này rất phổ biến trong người Việt Nam vì theo họ, có cõi Tây Phương Cực Lạc (Sukhàvati hay Tây Phương Cực Lạc) do Đức Phật Vô Lượng Quang (Amitabha) chủ trì và là nơi dẫn dắt linh hồn người chết. Bằng cách gọi tên ngài, tín đồ có thể đến được cõi này nhờ lời cầu xin ân sủng từ Bồ Tát Quán Thế Âm làm người cầu thay. Theo nhà nghiên cứu Việt Nam Nguyễn Thế Anh, chính nhà sư Thảo Đường được vua Lý Thánh Tôn đưa về nước trong chuyến viễn chinh sang Chiêm Thành (Đồng Dương), người đã đề xuất quá trình giác ngộ này bằng trực giác và làm tê liệt tâm trí bằng cách niệm danh hiệu Đức Phật. Đây cũng là lý do tại sao Phật tử Việt Nam thường nói A Di Đà (Amitabha) thay vì từ « xin chào » khi gặp nhau.

Sơ đồ bố trí nội thất của chùa chữ Công

Cuối cùng, trên bệ cuối cùng, thấp hơn và rộng hơn hai bệ kia, là tượng Phật Thích Ca Mâu Ni, Đức Phật của Hiện Tại, và hai vị đại đệ tử của ngài: Đại Ca Diếp (Kasyapa) và Tôn Giả A Nan (Ananda). Ở một số chùa, có bệ thứ tư mô tả Đức Phật của Tương Lai, Di Lặc, bên phải là Bồ Tát Phổ Hiền Bồ Tát, biểu tượng của sự thực hành, và bên trái là Bồ Tát Văn Thù Sư Lợi, biểu tượng của trí tuệ. Số lượng tượng được trưng bày trên các bệ thờ khác nhau tùy thuộc vào danh tiếng của ngôi chùa. Phần lớn là nhờ vào sự cúng dường của các tín đồ. Đó là trường hợp chùa Mía có 287 bức tượng, chùa Trăm Gian (Hà Tây) có 153 bức tượng, v.v.Hàng cuối cùng của chùa (hay hậu đường) tương ứng với gian sau và có tính chất đa chức năng. Một số chùa dành nơi này làm nơi ở của người tu hành (tăng đường). Một số chùa khác lại dùng làm nơi thờ cúng các bậc hiền tài, anh hùng như Mạc Đĩnh Chi (chùa Dâu) hay Đặng Tiến Đông (chùa Trăm Gian, Hà Tây). Chính vì vậy mà chúng ta thường nói: tiền Phật hậu Thần (trước Phật, sau Thần). Đây là mô hình ngược lại mà chúng ta thường thấy ở đình chùa: Tiền Thần, Hậu Phật. (trước Phật, sau Phật). Đôi khi có gác chuông hoặc lầu Manes dành cho người đã khuất.

Đôi khi, một căn phòng hoặc bàn thờ được dành riêng cho những người đã đầu tư nhiều tiền vào việc xây dựng hoặc bảo trì chùa. Hầu hết những người cúng dường là phụ nữ, những người có ảnh hưởng đáng kể đến các vấn đề của nhà nước. Đây là trường hợp của công chúa Mía, một trong những phi tần của Chúa Trịnh. Một bàn thờ gần với bàn thờ của Đức Phật đã được dành riêng cho bà tại chùa Mía. Trong chùa Bút Tháp, có một phòng dành riêng để tôn kính những người cúng dường nữ như hoàng hậu Trịnh Thị Ngọc Cúc, các công chúa Lê Thị Ngọc Duyên và Trịnh Thị Ngọc Cơ. Đây là những người đã đóng góp tài chính cho việc xây dựng ngôi chùa này vào thế kỷ 17.

Phía sau chùa, người ta có thể tìm thấy một khu vườn với các bảo tháp hoặc một ao súng. Đây là trường hợp của chùa Phát Tích, với sân sau có 32 bảo tháp với kích thước khác nhau trong vườn. Hình dạng của chữ Đinh (丁) đôi khi được tìm thấy trong bố cục bên trong của chùa Việt Nam. Đây là dấu hiệu thứ tư của chu kỳ thập phân được sử dụng trong lịch Trung Quốc. Đây là trường hợp của chùa Nhất Trụ do vua Việt Nam Lê Đại Hành xây dựng tại Hoa Lư (Ninh Bình), cố đô của Việt Nam, và chùa Phúc Lâm (Tuyên Quang) được xây dựng dưới thời nhà Trần (thế kỷ 13-14).

Chữ mà hầu hết các ngôi chùa Việt Nam thường sử dụng trong thiết kế nội thất là chữ Công (工). Bên cạnh các dãy chính được thiết kế tỉ mỉ bên trong chùa, còn có hai hành lang dài nối tiền đường với hậu đường. Điều này tạo thành một khung hình chữ nhật, bao quanh các dãy chính đã được đề cập trước đó trong chữ Tam. Cách sắp xếp này trông giống chữ Công bên trong chùa, nhưng nhìn từ bên ngoài lại giống chữ Quốc (国), với khung được hoàn thiện bởi hai hành lang dài.

The Nùng are part of the Tày-Thái group of the Austro-Asiatic ethnolinguistic family. According to foreign ethnologists, they are related to the Tày of Vietnam and the Zhuang or Choang (dân tộc Tráng) of China. Although the Tày and the Nùng speak their respective languages, they manage to understand each other perfectly. Their languages differ slightly in phonetics but are similar in vocabulary use and grammar. The Tày were present at the end of the first millennium BC.

This is not the case for the Nùng. Their settlement in Vietnam dates back to only about 300 years ago. However, their presence in southern China (Kouang Si (Quảng Tây), Kouang Tong (Quảng Ðông), Yunnan (Vân Nam), Guizhou (Qúi Châu), and Hunan (Hồ Nam)) is not very recent. They were also one of the ethnic groups of the Austro-Asiatic Bai Yue or Hundred Yue (Bách Việt) group. Also known under the name Tây Âu (Si Ngeou or Âu Việt) at a certain time, they played a major role in the founding of the second kingdom of Vietnam, the Âu Lạc kingdom of An Dương Vương, but they also engaged in relentless struggle against the Chinese expansion led by Emperor Qin Shi Huang Di (Tần Thủy Hoàng) with the Luo Yue (the Proto-Vietnamese). They also participated in the uprising of the two Vietnamese heroines Trưng Trắc and Trưng Nhị in the reconquest of independence under the Han dynasty.

They continue to preserve to this day many memories and legends about these two heroines in Kouang Si.

At a certain distant time, the Nùng were considered a branch of the Luo Yue living in the mountains before being definitively given the name « Choang » because they are closer to the Tày and the Thais than to the Vietnamese in terms of social organization and language. By calling themselves Cần Slửa Ðăm (people with black clothes) (người mặc áo đen), they claim to be different from the Tày, who are known as Cần Slửa Khao (people with white clothes) (người mặc áo trắng). Despite their clothes being the same indigo color, both peoples do not dress in the same way. This observation was noted by the Vietnamese writer Hữu Ngọc Hoàng Nam, author of the first monographic essay on the Nùng in Vietnam, who highlighted an important remark about the meaning of the words Đăm and Khao. For him, these allow the identification and distinction of subgroup membership within the Tày-Thai linguistic group through differences in clothing colors, dialects, and customs. Those belonging to Đăm (black or Đen in Vietnamese) include the Nùng, Black Thái, Thái, Black Hmongs, Black Lolo, etc., and those belonging to Khao (white or trắng in Vietnamese) include the Tày, White Thái, Lao (or Dao), White Lolo, White Hmongs, etc.