The hospitality that Rama I extended to Nguyễn Ánh later served as the basis for the development of the future relationship between the two countries. It is not unrelated to Nguyễn Ánh’s careful conduct in seeking an appropriate solution to manage the dual suzerainty over Laos and Cambodia with the Thais. According to the Vietnamese researcher Nguyễn Thế Anh, these countries were considered at that time as children raised together by Siam and Vietnam, the former arrogating the title of father and the latter the title of mother. This dual dependence is known in the Thai language as « song faifa. » According to Siamese sources, Nguyễn Ánh sent six times from Gia Định to Bangkok silver and gold trees, a sign of allegiance between 1788 and 1801. (2). In a letter addressed to Rama I before his return to Gia Định, Nguyễn Ánh agreed to be placed under the protectorate of Siam in case he succeeded in restoring his power. Did Đại Nam (the former name of Vietnam) accept being a mandala state?

There are several reasons to refute this hypothesis. First, Đại Nam was not under the influence of Theravada Buddhism and did not have the Indianized culture as was the case with Cambodia and Laos because the religious role plays an important part in the mandala defined by the researcher O. Wolter. Siam had so far tried to extend its influence and control in regions where the Thais were more or less established and where the Indianized culture was visible.

This is not the case for Vietnam. Chakri and his predecessor Taksin had already failed in this endeavor in Cochinchina, which was nevertheless a new land because there was a significant Vietnamese colony with a different culture. Vassalage seems unlikely. The truth is never known, but one can rely on the fact that to acknowledge the benefits of Ralma I, Nguyễn Ánh could adopt this understandable behavior which was never incompatible with his temperament and especially with his Confucian spirit, in which ingratitude was not a part.

One always finds in him the gratitude and kindness that cannot later be refuted with Pigneau de Béhaine, who devoted much effort to convincing him to convert to Catholicism. During his reign, there was no persecution of Catholics, which can be interpreted as a recognition of Pigneau de Béhaine. From this point of view, one can see in him the principle of humanity (đạo làm người) by honoring both the gratitude towards those who protected him during 25 years of hardships and the revenge against those who killed all his relatives and family. (debt must be repaid, vengeance must be taken)

At the time of his enthronement in 1803 in Huế, Nguyễn Ánh received a crown offered by King Rama I but immediately returned it because he did not accept being treated as a vassal king and receiving the title that the Siamese King Rama I was accustomed to granting to his vassals. This behavior disproves the accusation that has always been made against Nguyễn Ánh.

For some Vietnamese historians, Nguyễn Ánh is a traitor because he brought in foreigners and gave them the opportunity to occupy Vietnam. The Vietnamese expression « Đem rắn cắn gà nhà » (Introducing the snake to bite the home chicken) is often attached to Nguyễn Ánh. It is unfair to label him a traitor because, in the difficult context he was in, there was no reason not to act as he did as a human being when he was at the brink of despair. Probably the following expression « Tương kế tựu kế » (Combining a stratagem of circumstance) suits him better, although there is a risk of playing into the hands of foreigners. It should also be recalled that the Tây Sơn had the opportunity to send an emissary to Rama I in 1789 with the aim of neutralizing Nguyễn Ánh using the stratagem (Điệu hổ ly sơn (Luring the tiger away from the mountain)), but this attempt was in vain due to Rama I’s refusal. (3)

Being intelligent, courageous, and resigned like the king of the Yue Gou Jian (Cẫu Tiển) from the Spring and Autumn period (Xuân Thu), he should have known the consequences of his act. There is not only Gia Long but also thousands of people who accepted to follow him and bear the heavy responsibility of bringing foreigners into the country to counter the Tây Sơn. Are they all traitors? This is a thorny question to which it is difficult to give an affirmative answer and a hasty condemnation without first having a sense of fairness and without being swayed by partisan opinions when one knows that Nguyễn Huệ remains the most adored hero by the Vietnamese for his military genius.

Disappointed by Gia Long’s refusal, Rama I showed no sign of resentment but found justification in the cultural difference. In Rama I, we find not only wisdom but also understanding. He wanted to deal henceforth on an equal footing with him. This equal treatment can be interpreted as a « privileged » bilateral relationship between the elder and the younger in mutual respect. Each of them should know that they needed the other even if it was an alliance of circumstance. Their countries were respectively threatened by formidable enemies, Burma and China.

Their special relationship did not fade over time because Rama I fell in love in the meantime with Nguyễn Ánh’s sister. It is not known what became of her (his wife or his concubine). However, there was a love poem that Rama I dedicated to her and which continued to be sung even in the 1970s during the annual royal boat procession.

As for Nguyễn Ánh (or Gia Long), during his reign, he avoided military confrontation with Thailand over the thorny Cambodian and Laotian issues. Before his death, Gia Long repeatedly reminded his successor Minh Mạng to perpetuate the friendship he had managed to establish with Rama I and to consider Siam as a respectable ally in the Indochinese peninsula (4). This was later justified by Minh Mạng’s refusal to attack Siam at the request of the Burmese.

According to researcher Nguyễn Thế Anh, in continental Southeast Asia, out of about twenty important principalities around 1400, only three kingdoms remained that managed to establish themselves at the beginning of the 19th century as regional powers, among which were Siam and Đại Việt, one advancing eastward and the other southward at the expense of the Hinduized states (Laos, Cambodia, Champa). This conflict of interests intensified increasingly after the death of Rama I and Nguyễn Ánh.

Their successors (Minh Mạng, Thiệu Trị on the Vietnamese side and Rama III on the Siamese side) were entangled in the problem of succession of the Cambodian kings who kept fighting among themselves and seeking their help and protection. They were henceforth guided by a policy of colonialism and annexation which led them to confront each other militarily twice in 1833 and 1841 on Cambodian and Vietnamese territories and to find at the end of each confrontation a compromise agreement in their favor and to the detriment of their respective protégés.

The temporary alliance is no longer taken into account. The rivalry, which was becoming increasingly visible between the two competing countries Đại Nam and Siam, now rules out any rapprochement and any possible alliance. Even their policies are completely different, one aligning with the Chinese model to avoid any contact with Western colonialists and the other with the Japanese model to advocate the opening of borders.

The Khmer capital Phnom Penh was at one time occupied by the Vietnamese army of General Trương Minh Giảng while the regions of Western Cambodia (Siem Reap, Battambang, Sisophon) were in the hands of the Thais. According to the French historian Philippe Conrad, the king of Cambodia was considered a mere governor of the king of Siam. The royal insignia (golden sword, crown seal) were confiscated and held in Bangkok. The arrival of the French in Indochina put an end to their dual suzerainty over Cambodia and Laos. It allowed the Cambodian and Laotian protégés to recover part of their territory in the hands of the Vietnamese and the Thais. Đại Nam under Emperor Tự Đức had to face the French colonial authorities who had annexed the six provinces of Nam Bộ (Cochinchina).

Thanks to the foresight of their kings (particularly that of Chulalongkorn or Rama V), the Thais, relying on the rivalry policy between the English and the French, managed to maintain their independence at the cost of territorial concessions (the Burmese and Malay territories occupied were returned to the English and the Laotian and Khmer territories to the French). They chose a flexible foreign policy (chính sách cây sậy) like the reed that adapts to the wind. It is no coincidence to see the sacred union of the three Thai princes at the dawn of the Thai nation in 1287 and the submission to the Sino-Mongol troops of Kublai Khan.

It is this synthetic policy of adaptation that allows them to stay away from colonial wars, always side with the victors, and exist today as a flourishing nation despite their late emergence (dating from the early 14th century) in mainland Southeast Asia.

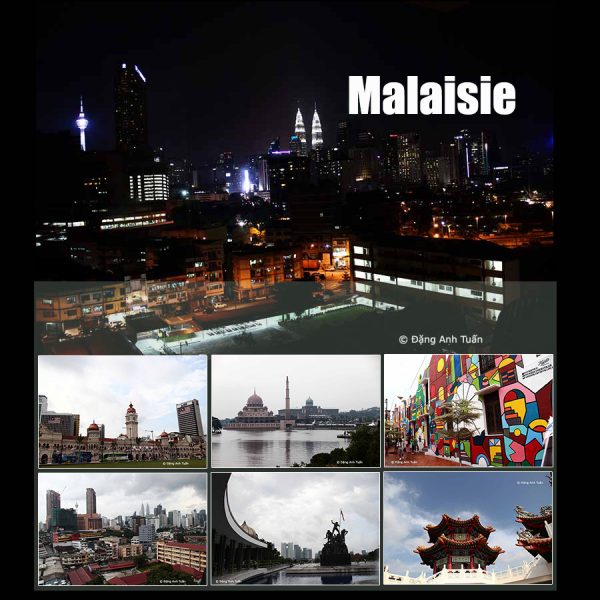

Pictures of Venice of the East (Vọng các)

(1) Bùi Quang Tùng: Professeur, membre scientifique de EFEO. Auteur de plusieurs ouvrages sur le Vietnam.

(2) P.R.R.I, p. 113.

(3) Pool, Peter A.: The Vietnamese in Thailand, p 32, note 3.