Version française

Version vietnamienne

Galerie des photos

The emergence of the Thai only became firmly established in the 14th century. Yet they are an ancient people of southern China. They are part of the Austro-Asiatic group (Chủng Nam Á) (or Baiyue or Bách Việt in Vietnamese). It is this group that the French archaeologist Bernard Groslier often referred to as the « Thai-Vietnamese group.

Repulsed by the Tsin of Shi Huang Di, the Thai tried to resist many times. For the Vietnamese writer Bình Nguyên Lôc, the subjects of the Shu and Ba kingdoms (Ba Thục) annexed very early by the Tsin in Sichuan (Tứ Xuyên)(1) were the proto-Thais (or Tay). According to this writer, they belonged to the Austro-Asiatic group of the Âu branch (or Ngu in Mường language or Ngê U in Mandarin Chinese (quan thoại)) to which the Thai and the Tày were attached.

For him, as for other Vietnamese researchers Trần Ngọc Thêm, Nguyễn Đình Khoa, Hà Văn Tấn etc., the Austro-Asiatic group includes 4 distinct subgroups: Môn-Khmer subgroup, Việt Mường subgroup (Lạc branch), Tày-Thái subgroup (Âu branch) and Mèo-Dao subgroup to which must be added the Austronesian subgroup (Chàm, Raglai, Êdê etc.) to define the Indonesian (or proto-Malay) race (2) (Chủng cổ Mã Lai).

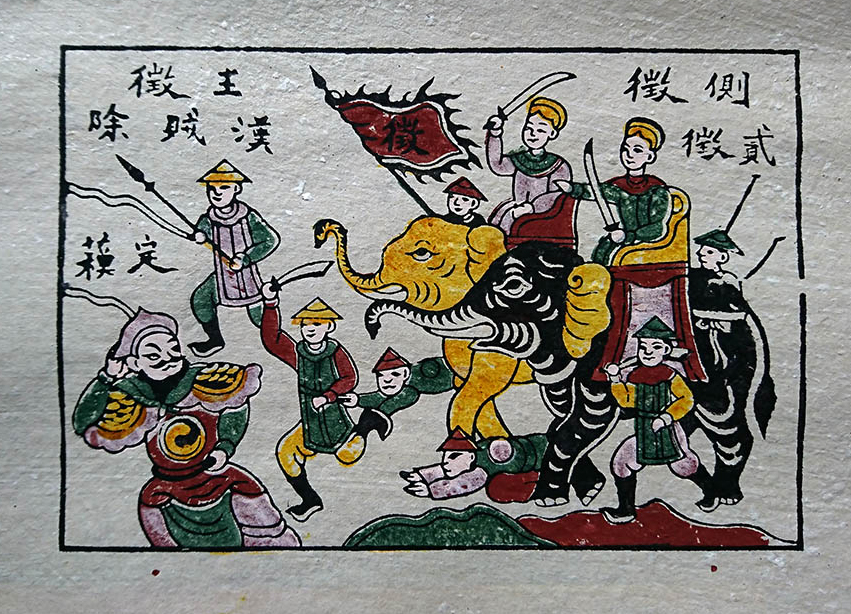

The Thai contribution to the founding of the Au Lac Kingdom of the Viet of Thục Phán (An Dương Vương) is no longer in doubt after the latter succeeded in eliminating the last Hùng king of the Văn Lang kingdom because the name « Au Lac » (or Ngeou Lo) obviously evokes the union of two Yue ethnic groups of the Au branch (Proto-Thai) and the Lac branch (Proto-Viet). Moreover, Thục Phán was a Yue of the Au branch, which shows to such an extent the union and the common historical mission of these two ethnic groups in the face of Chinese expansion. According to Đào Duy Anh, Thục Phán was a prince of the Shu kingdom.This is what was reported in Chinese historical writings (Kiao-tcheou wai-yu ki or Kouang-tcheou ki), but it was categorically refuted by some Vietnamese historians because the Shu kingdom was located too far at that time, from the Văn Lang kingdom. It was annexed very early (more than half a century before the foundation of the Âu Lạc kingdom) by the Tsin. But for the Vietnamese writer Bình Nguyên Lôc, Thục Phán having lost his homeland, had to take refuge very young in the company of his faithful at that time in a country having the same ethnic affinity (culture, language) as him, namely the Si Ngeou kingdom (Tây Âu) located next to the Văn Lang kingdom of the Vietnamese. Furthermore, the Chinese have no interest in falsifying history by reporting that it was a prince of Shu ruling the kingdom of Âu Lạc. The asylum of the latter and his followers in the kingdom of Si Ngeou must have taken some time, which explains at least half a century in this exodus before the foundation of his kingdom Âu Lạc. This hypothesis does not seem very convincing because there was a 3000 km walk. In addition, he was at the head of an army of 30,000 soldiers. It is impossible for him to ensure logistics and make his army invisible during the exodus by crossing mountainous areas of Yunnan administered by other ethnic groups who were enemies or loyal to the Chinese. It is likely that he had to find from the Si Ngeou (or the Proto-Thais) everything (armament and military personnel, provisions) that he needed before his conquest.

There is recently another hypothesis that seems more coherent. Thục Phán was the leader of a tribe allied to the Si Ngeou confederation and the son of Thục Chế, king of a Nam Cương kingdom located in the Cao Bằng region and not far from Kouang Si in today’s China. There is a total concordance between everything reported in the legend of the magic crossbow of the Vietnamese and the rites found in the tradition of the Tày (Proto-Thai). This is the case of the golden turtle or the white rooster, each having an important symbolic meaning. An Dương Vương (Ngan-yang wang) was a historical figure. The discovery of the remains of its capital (Cổ Loa, huyện Đông An, Hànội) no longer casts doubt on the existence of this kingdom established around three centuries BC. It was later annexed by Zhao To (Triệu Đà), founder of the kingdom of Nan Yue.

Lac Long Quan-Au Cơ myth cleverly insinuates the union and separation of two Yue ethnic groups: one of the Lac branch (the Proto-Vietnamese) descending into the fertile plains following the streams and rivers, and the other of the Au branch (the Proto-Thai) taking refuge in the mountainous regions. The Muong were among the members of this exodus. Linguistically close to the Vietnamese, the Muong managed to preserve their ancestral customs because they were pushed back and protected in the mountains. They had a social organization similar to that of the Tày and the Thai. Located in the provinces of Kouang Tong (Quãng Đông) and Kouang Si (Quãng Tây), the kingdom of Si Ngeou (Tây Âu) is none other than the country of the proto-Thais (the ancestors of the Thais). It is here that Thục Phán took refuge before the conquest of the Văn Lang kingdom. It should also be remembered that the Chinese emperor Shi Houang Di had to mobilize at that time more than 500,000 soldiers in the conquest of the kingdom of Si Ngeou after having succeeded in defeating the army of the kingdom of Chu (or Sỡ) with 600,000 men. We must think that in addition to the implacable resistance of its warriors, the kingdom of Si Ngeou would have to be of a significant size and populated enough for Shi Houang Di (Tần Thủy Hoàng) to engage a significant military force.

Despite the premature death of a Si Ngeou king named Yi-Hiu-Song (Dịch Hu Tống), the resistance led by the Thai or (Si Ngeou)(Tây Âu) branch of the Yue managed to achieve some expected successes in the southern Kouang Si region with the death of a general T’ou Tsiu (Uất Đồ Thu) at the head of a Chinese army of 500,000 men, which was recorded in the annals of Master Houa-nan (or Houai–nan–tseu in Chinese or Hoài Nam Tử in Vietnamese) written by Liu An (Lưu An), grandson of Emperor Kao-Tsou (or Liu Bang), founder of the Han Dynasty between 164 and 173 BCE.

Si Ngeou was known for the valor of his formidable warriors. This corresponds exactly to the temperament of the Thais of yesteryear described by the French writer and photographer Alfred Raquez:(3)

Being warlike and adventurous, the Siamese of yesteryear were almost continually at war with their neighbors and often saw their expeditions crowned with success. After each successful campaign, they took prisoners with them and settled them in a part of the territory of Siam, as far as possible from their country of origin.

After the disappearance of Si Ngeou and Âu Lạc, the proto-Thais who remained in Vietnam at that time under the rule of Zhao To (a former Chinese general of the Tsin who later became the first emperor of the kingdom of Nanyue) had their descendants forming today the Thai ethnic minority of Vietnam. The other proto-Thais fled to Yunnan where they united in the 8th century with the kingdom of Nanzhao (Nam Chiếu) and then with that of Dali (Đại Lý) where the Buddhism of the Great Vehicle (Phật Giáo Đại Thừa) began to take root. Unfortunately, their attempt was in vain. The Shu, Ba, Si Ngeou, Âu Lạc (5), Nan Zhao, Dali countries were part of the long list of countries annexed one after the other by the Chinese during their exodus. In these subjugated countries, the presence of the Proto-Thais was quite significant. Faced with this relentless Chinese pressure and the inexorable barrier of the Himalayas, the Proto-Thais were forced to descend into the Indochinese peninsula (4) by slowly infiltrating in a fan-like manner into Laos, the North-West of Vietnam (Tây Bắc), the north of Thailand and upper Burma.

According to historical Thai inscriptions found in Vietnam, there were three major waves of migration initiated by the Thais from Yunnan into Northwest Vietnam during the 9th to 11th centuries. This corresponds exactly to the period when the kingdom of Nanzhao was annexed by the kingdom of Dali, which in turn was destroyed three centuries later by the Mongols of Kublai Khan in China. During this infiltration, the proto-Thais divided into several groups: the Thais of Vietnam, the Thais in Burma (or Shans), the Thais in Laos (or Ai Lao), and the Thais in northern Thailand. Each of these groups began to adopt the religion of their host countries. The Thais of Vietnam did not have the same religion as those in other territories. They continued to maintain animism (vạn vật hữu linh) or totemism.

This is not the case for the Thais living in northern Thailand, Upper Burma, and Laos. These areas were occupied at that time by Indianized Mon-Khmer kingdoms and Theravada Buddhist kingdoms (Angkorian empire, Mon Dvaravati kingdoms, Haripunchai, Lavo, etc.) after the disintegration of the Indianized Founan (Phù Nam) kingdom. The Mons played an important role in transmitting Theravada Buddhism from the Sinhalese tradition to the newly arrived Thais.

It can be said that to the two main components of the Thai religion (worship of geniuses (Phra) and spirits (Phi) and Theravada Buddhism) is added Hinduism. The latter played a very important role in Southeast Asia before Theravada Buddhism succeeded in establishing itself and embracing Burma, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia.

There are as many geniuses as malevolent spirits in the Thai pantheon. This animist belief is not incompatible with Theravada Buddhism because the Thais place protective deities (the phra) at an intermediate level between humans and Hindu gods closely linked to Theravada Buddhism. They are, in a way, servants of the Buddha. Buddhism tolerates local rites. That is why one often finds a small temple carefully maintained and dedicated to Brahma with four faces (Thần Bốn Mặt) around important Thai buildings, in order to allow this deity to ward off malevolent spirits and protect these places. Other deities have not gone unnoticed in public places (pagodas, airports, royal palace, etc.).

Having arrived late in these host countries, the Thais initially had to take on all the « ungrateful » jobs. Because their skin was dark, the Khmers called them by the name Syàma (Xiêm La), a Sanskrit word meaning « tanned. » It is under this name that they were mentioned around 1050 in one of the Cham inscriptions of Po Nagar (Nha Trang) as prisoners of war during the confrontation between the Chams and the Khmers of the Angkorian empire. They also appeared as daring scouts, mercenaries of the Angkorian empire’s army, whose presence was reported in one of the bas-reliefs of Angkor Wat. According to the French archaeologist Bernard Groslier, they were merely unruly hill people, without writing or religion. They had no chance of even shaking the border posts of the Khmer empire and the Mon kingdoms of Dvaravati culture.

This is not the case for the Vietnamese who began to challenge Champa at the same time because, according to Bernard Groslier, the latter already constituted a nation remarkably equipped by Chinese civilization during the long domination, and could engage in the struggle on equal terms with the Chams. The Thais had to wait at least two centuries to assimilate the lessons of their masters before being able to replace and subsequently surpass them. Coming from the north and in frequent contact with the Dvaravati culture, they quickly converted to Theravāda Buddhism (or the Little Vehicle) or (Phật Giáo Nguyên Thủy in Vietnamese) but continued to maintain their social structure organized into powerful feudal chiefdoms (or mường).

For the Thais, Thailand is still considered the great and powerful chiefdom (Mueang of the free Thais or Mường của các người Thái tự do). Even paradise is organized into chiefdoms administered by deities (or the Devata). This is what has been reported by the Thais of Vietnam. This aligns with Alfred Raquez‘s observation on the common practice of the Siamese in grouping their prisoners into chiefdoms:

The Siamese did not scatter their prisoners throughout the kingdom. On the contrary, they kept them grouped together, forming khong at the head of which they placed chiefs of the same origin or naïkhong. These, supreme magistrates, handled all the affairs of the community and were almost the only ones in direct contact with the country’s authorities.

The chieftaincy is at the base of the social, religious, and political organization of the Thais. The chieftaincies are considered small (mường nhỏ) or large (mường lớn) depending on their size and importance. This corresponds respectively to what we have in France with the district or the province. But there is always a central chieftaincy (mường luông) towards which the other chieftaincies converge. This is what we observe in the organization of Thai chieftaincies in Vietnam. Each chieftaincy is led by a chief or a lord from the local aristocracy who also has an important religious role. He is responsible for maintaining the cult of the spirit of the land. That is why he has precedence over the villagers. They owe him not only armed service in case of war but also corvée labor. Each chieftaincy has its own customs. Its administrative and military organization resembles that of the Mongols, which allows distinguishing the nobles and warriors from the rest (the petty kings and serf peasants). Each has his rank or status in a system called sakdina (sakdi meaning power and na meaning rice field). Suppose each peasant owns 25 rai (an amount of land equivalent to 1600 m2 or rẫy in Vietnamese). A boss with a grade of 400 in sakdina can have 16 peasants under his command because 16 = 400/25. As for a noble or a lord, he can have 400 people under his command if his grade rises to 10,000 in the sakdina system. (400 = 10,000/25). In short, depending on his rank, he can have a certain number of people for the system of civil and military duties.

Each chiefdom is made up of several hamlets (or thôn in Vietnamese), each managed by a council of notables and having 40 or 50 houses except for some that can reach up to 100 houses. Similar to the Vietnamese, the Thais generally establish their hamlet and their chiefdom in alluvial plains (such as that of the Chao Praya) and in regions with significant waterways conducive to flooded rice cultivation, transportation, and the interconnection of roads to facilitate exchange with other Thai chiefdoms.

Galerie des photos

Taking advantage of the exhaustion of the Angkorian empire due to incessant wars against its neighbors (Champa, Vietnam) and the gigantic construction works of the temples (Bayon, Angkor Thom, Ta Prohm, Angkor Wat, etc.) of Jayavarman VII, the death of the latter, and the Mongol invasion against Indochina (the Khmer empire in 1283, Champa (1283-1285), Đại Việt (or Vietnam) of the Trần (1257-1288)) and against the kingdom of Pagan (Burma), the Thais began to establish their political power both in Thailand and in Burma.

In Thailand, on the northern edge of the Menam basin, two Thai princes named Po Khun Bangklanghao and Po Khun Phameung succeeded in freeing Sukhothai from the control of the Mon and the Khmers in 1239. Po Khun Bangklanghao thus became the first king of the independent Thai kingdom of Sukhothai, whose name means « the dawn of happiness. » But it was rather his son Rama Khamheng who had the great task of expanding the Thai kingdom by conquering not only northern Malaysia up to Ligor (or Nakhon Si Thammarat) but also Khmer possessions near Luang Prabang (Laos). At the same time, in northern Thailand, after the annexation of Haripunjaya in 1292, another allied Thai prince named Mengrai founded his kingdom Lannathai (kingdom of a million rice fields) by making Chiang Mai the capital. Rama Khamheng and Mengrai, two Thai princes, now shared dominion, one in the center and the other in the north of Thailand. Other small Thai kingdoms were created in Phayao and in Xiang Dong Xiang Thong (Luang Prabang) in Laos. In Burma, the kingdom of Pagan failed to resist the Mongol invasion. The Thais of Burma (or the Shan) took advantage of this opportunity to break the kingdom into several Shan states.

(1): Land of pandas. It is also here that the Ba-Shu culture was discovered, famous for its zoomorphic masks of Sanxingdui and for the mystery of the signs on the armor. It is also the Shu-Han kingdom (Thục Hán) of Liu Bei (Lưu Bị) during the Three Kingdoms period. (Tam Quốc)

(2): Race of prehistoric Southeast Asia.

(3): Comment s’est peuplé le Siam, ce qu’est aujourd’hui sa population. Alfred Raquez, (publié en 1903 dans le Bulletin du Comité de l’Asie Française). In: Aséanie 1, 1998. pp. 161-181.

(4): Indochina in the broad sense. It is not French Indochina.