Giải mã những thông điệp mà người Việt cổ để lại trong truyền thuyết.

Văn hóa Lương Chử và Thạch Gia Hà.

Décrypter les messages laissés par les Proto-Vietnamiens dans leurs légendes.

Cultures de Lianzhu et Shijahé.

Version française

English version

Tại sao dân tộc Việt có nhiều chuyện cổ tích và truyền thuyết hơn mọi dân tộc khác trong vùng Đông Nam Á? Đôi khi làm người đọc tự hỏi các truyền thuyết nầy có thật hay không hay là được viết ra do sự tưởng tượng của con người, có phần kì ảo và không có thật. Thật sự nguồn gốc của người Việt rất mơ hồ trong lịch sử bởi vì chỉ dựa trên các truyền thuyết đôi khi còn làm ta khó tin và phi lý như truyền thuyết «Lạc Long Quân-Âu Cơ » với cái bọc nở ra một trăm trứng.

Đối với nhà nghiên cứu Paul Pozner [1], thuật chép sử Việt Nam đều dựa trên truyền thống lịch sử lâu dài và vĩnh cửu và được thể hiện bởi cách truyền miệng kéo dài từ nhiều thế kỷ của thiên niên kỷ đâu tiên trước công nguyên dưới hình thức các truyền thuyết lịch sử được phổ biến ở trong các đền thờ cúng tổ tiên. Tại sao dân tộc ta không có được sử sách như người Trung Hoa tuy có sự hiện diện lâu đời ở Đông Nam Á. Nơi nầy còn được xem là cái nôi của nền văn minh nhân loại qua sự nhận xét của nhà vật lý người Anh Stephen Oppenheimer trong tác phẩm «Địa đàng ở phương Đông» [2]. Chính cũng ở đất nước ta với các cuộc khai quật ở đầu thế kỷ 20 mà nhà khảo cổ Pháp Madeleine Colani khám phá được văn hoá Hòa Bình (18000-10000 TCN) vào năm 1922. Đây cũng là một nền văn hoá khởi nguồn cho nền văn minh của người Việt cổ, một nền văn minh trồng lúa nước. Sở dĩ dân ta không có sử sách mà còn bị người Hoa thống trị có gần một ngàn năm. Lúc nào họ cũng cố tình xóa bỏ nguồn gốc của dân tộc ta từ thời nhà Hán với Hán Vũ Đế.

Sử ký của Tư Mã Thiên [3] đều viết có ý đồ chính trị và tham vọng của kẻ xâm lăng nhầm Hán hoá các dân tộc bị thống trị và tăng cường quyền lực và uy tín con của Trời (thiên tử) trong một quốc gia đa dạng về mặt dân tộc học và để phù hợp sau cùng với ý nghĩa hai chữ Trung Quốc ((zhōngguó) (中華)(centre de l’univers). Bởi vậy trong lịch sử Trung Hoa có nhiều chuyện hoang đường khó tin nổi lấy râu thằng A cắm qua thằng B nhất là thời tam hoàng ngủ đế. Tất cả điều này một phần lớn là do sự vay mượn các truyền thống, phong tục và các nhân vật thần thoại hoặc động vật từ các dân tộc mà họ đã thành công trong việc hán hóa. Các nhà nho giáo người Việt đôi khi cũng nhầm lẫn dựa trên sách vở của người Hán như trong Đại Việt Sử Ký Ngoại Kỷ Toàn Thư mà nói người Giao Chỉ (Việt cổ) (Jiaozhi) không biết cày cấy cần nhờ thái thú Cửu Chân thời nhà Tây Hán Nhâm Diên (Ren Yan) dạy dân khai khẩn ruộng đất, hàng năm cày trồng để cho trăm họ no đủ. Luôn cả các nhà khảo cổ phương Tây thì cũng vậy, cho rằng người Việt Cổ chỉ là những người sống bằng nghề đánh cá, săn bắn và hái lượm dựa trên sách vở của Trung Hoa.

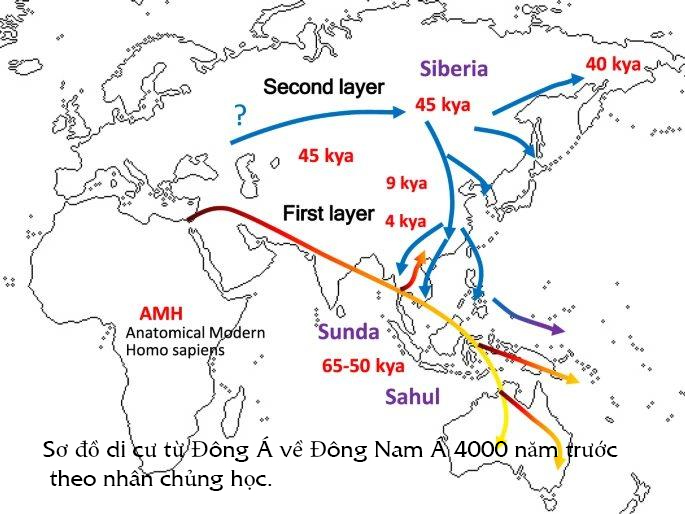

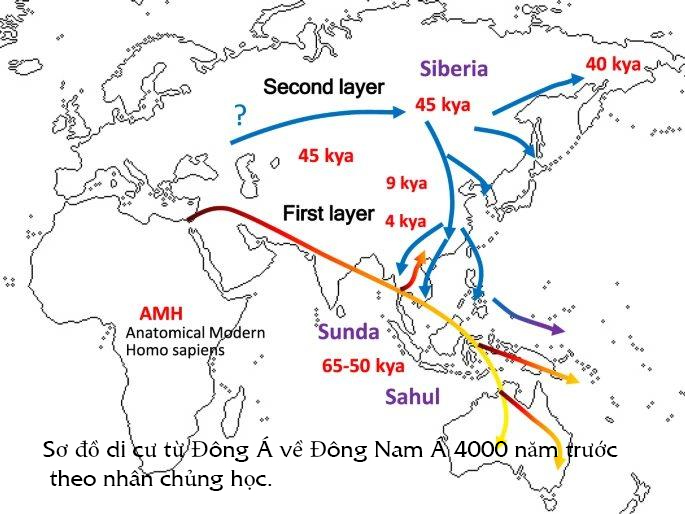

May thay nhờ các tài liệu nghiên cứu di truyền của Hugh McColl cùng nhóm đồng nghiệp [4] và các cuộc khai quật khảo cổ trong thời gian qua thì biết rõ ngày nay cư dân Hoà Bình là những người đầu tiên biết rõ về kỷ thuật trồng lúa nước và nông nghiệp khác như ngũ cốc vân vân…(Hang Ma chẳng hạn). Sau đó có một trận lụt lớn đã xảy ở thời điểm 12000 năm trước khiến làm một phần lớn đất đai mà các nhóm cư dân tiền sử sinh sống như lưu vực sông Hồng đã chìm xuống dưới biển khiến buộc lòng họ phải mạo hiểm di tản khắp mọi nơi phía nam ở Châu Đại Dương, phía đông ở Thái Bình Dương hoặc phía tây ở Ấn Độ hay phía bắc ở vùng sông Dương Tử mang theo đặc trưng văn hóa Hòa Bình với di chỉ Tiên Nhân động (Xian Ren Dong) chẳng hạn ở Giang Tây (Jiangxi). Họ có dừng chân ở lưu vực sông Dương Tử vì nơi nầy thuận lợi ở thời điểm đó cho việc phát triển trồng lúa nước. Rồi có một nhóm người vẫn tiếp tục hành trình đi lên vùng Đông Á, đem theo lúa đã được họ thuần hóa (di chỉ Thường Sơn, Shangshan) qua ngã Chiết Giang (Zhejiang) và kê để rồi định cư không những ở đồng bằng sông Hoàng Hà mà còn lên đến tận vùng sông Liêu (Nội Mông). Chính họ hợp nhất ở nơi nầy vớí cư dân cổ Bắc Á, những người du mục có dấu tích ở hang Devil’s Gate thuộc vùng lãnh thổ Nga giáp ranh giới với Triều Tiên (Tây Bá Lợi Á) mà tạo ra người Mongoloid phương Bắc điển hình và văn hoá Hồng Sơn được tìm thấy từ khu Nội Mông đến Liêu Ninh (Hoa Bắc).

Những người Mông Cổ phương Bắc còn tiến xuống vùng sông Hoàng Hà, nơi có người Miêu tộc cư trú và gỉỏi về làm ruộng. Họ được gọi là bộ tộc « Yi » Bởi vậy chữ tượng hình Yi 夷 được có nguồn gốc từ hình chữ người 人 có mang một cây cung 弓 Họ được nổi bật trong việc cởi ngựa bắn cung và họ rất thiện chiến. Bởi vậy họ dành thắng lợi với Hoàng Đế (Yandi) trong cuộc chiến tranh với người Miêu tộc do Xi Vưu (Chiyou) cầm đầu tại Trác Lộc (Zhuolu) ở Hà Bắc (Hebei) vào năm 2704 TCN, dẫn đến sự thành hình nền văn minh Hoa Hạ (Ngưỡng Thiều (Yangshao) và Đại Vấn Khẩu (Dawenkou)) và tạo ra chủng Mongoloïd phương Nam với cư dân cổ Đông Nam Á. Người Mongoloïd phương Nam càng ngày càng tăng số lượng và trở thành chủ nhân của lưu vực Hoàng Hà từ đó. Họ cũng là tổ tiên của người Hán (Trung Hoa) hiện đại. Ở lưu vực sông Dương Tử có sự thành hình cộng đồng tộc Việt Tai-Kadai từ sự gần gũi của các cư dân bản địa thuộc hệ ngữ Nam Á và cư dân tiền Nam Đảo, Tai-Kadai đến sau. Từ các yếu tố di truyền do sự hoà huyết giữa các cư dân bản địa và di cư mới đến với các làn sóng di cư từ Bắc Á xuống Nam Á và ngược lại qua cả nghìn năm khiến có sự thay đổi ở trong cấu trúc của gen nhất là có sự ảnh hưởng của môi trường sinh sống khiến có sự thay đổi dĩ nhiên về dáng vóc cũng như màu da và dẫn đến sự thành hình người Hoa Bắc, Hoa Nam cùng người Việt thuộc chủng Nam Á.

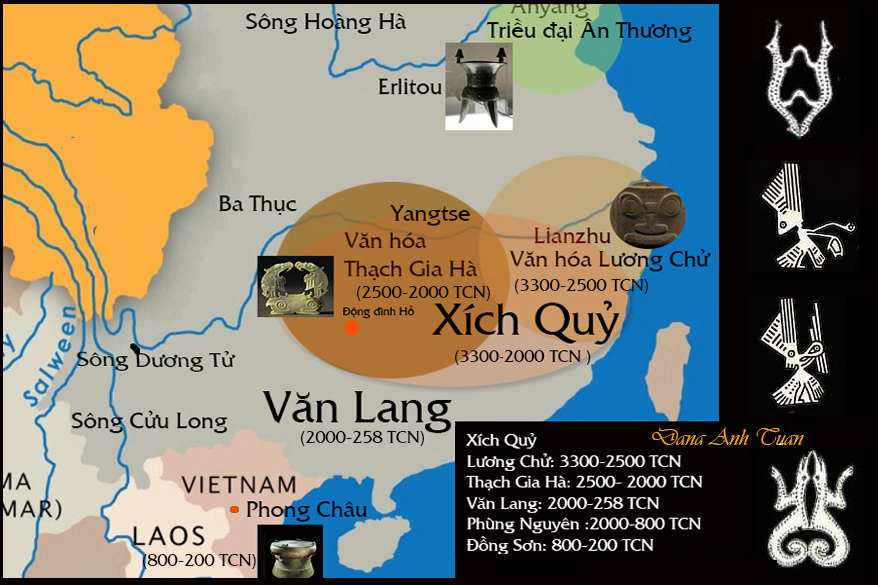

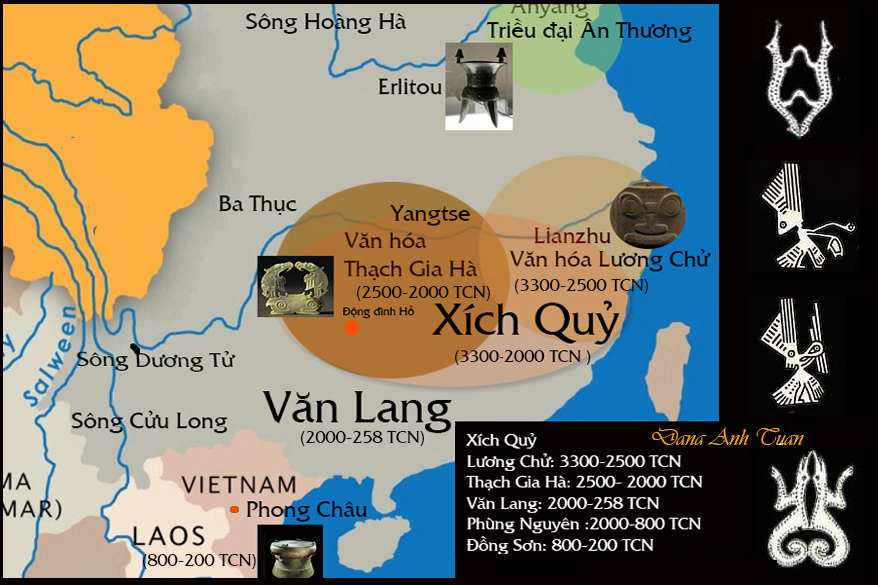

Chủng nầy là chủng tộc hợp nhiều sắc tộc ở Đông Á. Chính cũng ở nơi nầy mà tộc Việt nhận thức họ khác biệt rõ ràng với các tộc du mục ở khu vực sông Hoàng Hà. Họ tự xưng họ là Yue. Chữ « Việt (Yue 越 (rìu)) » mà họ dùng để tự xưng họ là cư dân sống ở khu vực sông Dương Tử hay có thói quen dùng chiếc rìu để canh tác trồng trọt và tự vệ khi có sự xâm lựợc của người Hoa Hạ chớ những người nầy lúc nào vẫn xem họ là Man Di. Chính họ dẫn đến sự thành hình các nền văn hóa lớn như Lương Chử (Liangzhu) và Thạch Gia Hà (Shijiahé) ở sông Dương Tử. Chính nhờ những cuộc khai quật khảo cổ ở phía hạ lưu sông Dương Tử vào thập kỷ 1970 mà chúng ta được biết đến văn hóa Lương Chử. Văn hoá nầy còn tiến bộ hơn nhiều lần so với văn hoá Ngưỡng Thiều (Yangshao) vì nó có từ 3.300 đến 2500 TCN với sự khám phá chữ tượng hình được khắc trên đá, yếm rùa, xương thú trong bói toán và cúng tế. Chữ nầy có sớm hơn Giáp cốt văn Ân Khư 2.000 năm.

Được biết người cư dân Lương Chử có một lối sống định cư ổn định cùng một hệ thống tưới tiêu bằng nguồn nước lưu giữ qua các kênh mương và một tổ chức xã hội cần nhiều nhân lực cho việc sản xuất và phân phối. Theo tài liệu khảo cổ và truyền thuyết nói về Thần Nông (sống khoảng 3320-3080) thì có sự trùng hợp hoàn toàn với nền văn hóa nầy.

Vua Thần Nông là vị vua đầu tiên ở phương nam còn phương bắc thì các tộc du mục được vua Hoàng Đế (người Hoa Hạ) cai trị. Theo học giả Hà Văn Thùy thì khoa học xác nhận, từ vật chứng ADN lấy trực tiếp trên di cốt Lương Chử thì dân cư xứ nầy gồm có hai dạng có mã di truyền M122 (chủng Indonesian) và M119 (chủng Melanesian). Hai chủng người nầy đa số đều người từ Đông Nam Á di cư lên Hoa lục cách đây 12000 năm trước. Hai chủng người nầy làm nên dân cư người Lương Chử. Các đồ tạo tác đặc trưng nhất của nền văn hóa Lương Chử là các đĩa bi có lỗ ở giữa và các tông mà tông lớn nhất được khai quật nặng 3,5 kg hay là những vật bằng ngọc thạch mang tính lễ nghi được làm một cách tinh xảo và thường được chạm khắc theo mô dạng thao thiết (taotie) hay là rìu. Những lưỡi cày bằng đá đạt đến kích thước lớn hơn nhiều, trong một số trường hợp dài tới 60 cm. Những chiếc máy cày thì chắc chắn do gia súc kéo (có thể là trâu).

Liềm, dụng cụ dùng để thu hoạch, cũng được trọng dụng đáng kể. Nền văn hóa nầy có hệ thống phân cấp xã hội thể hiện ở sự khác biệt về chôn cất trong các mộ đất của những người có quyền lực và qúi phái và những người nghèo.Trong các mộ của giới qúi phái thì các đồ vật dùng bằng ngọc bích, ngà, lụa hay sơn mài trong khi đó ở giới hạ lưu thì chỉ có đồ gốm. Các đĩa bi được sử dụng trong bối cảnh nghi lễ và thường có nhiệm vụ bảo vệ người về thế giới bên kia. Bi thường được kết nối với trời và màu xanh, trong khi tông, với hình dạng hình ống vuông ở bên ngoài và hình tròn bên trong, được liên kết với đất và màu vàng. Quan niệm nầy làm chúng ta nhớ đến hình dáng bánh chưng bánh dày của tộc Việt nhân dịp Tết nguyên đán.

Ngoài ra trên những hình thao thiết hay thường thấy «Thần nhân thú diện» tức là biểu hiệu của thần Xi Vưu thể hiện lòng can đảm theo học giả Hà Văn Thùy [5]. Còn theo nhà khảo cổ người Pháp Alain Thote thì đây là một biểu tượng nhận dạng mang tính cách ma lực tôn giáo và có ý tưởng liên quan đến cái chết khi ông nghiên cứu các thanh gươm của người Việt cổ (Ngô -Việt) ở thời Đông Châu Liệt Quốc [6]. Tuy thời gian quá cách xa từ văn hoá Lương Chử đến thời nhà Đông Châu có cả nhiều thế kỷ, việc chạm khắc trang trí «Thần nhân thú diện» trên các gươm không phải ngẫu nhiên nhất là chỉ trang trí một mặt và theo chiều hướng từ cán ra đến đầu lưởi gươm chắc chắn có ngụ ý cần đến sự che chở của thần nhân tức là thần Xi Vưu. Sau khi bị giết, ông được trở thành một vị thần chiến tranh nhầm bảo hộ các tộc người Việt trên đất Trung Hoa ở phương nam cùng chung một gốc trong đó có người Lương Chử được các học giả Trung Hoa xác nhận là Vũ Nhân (羽 人) hay Vũ dân, những người thờ vật Chim và Thú tức là Tiên Rồng (truyền thuyết Con Rồng Cháu Tiên).

Theo tự điển Hán nôm, chữ Vũ (羽) chỉ chung một loại chim. Tại sao Tiên Rồng? Từ thưở xưa, chim là loại vật có thể bay cao vượt núi đến bồng lai tiên cảnh, nơi cư ngụ của các tiên nữ. Còn rồng chắc chắn là thủy quái mà trong sử nước ta gọi là con thuồng luồng (giao long). Thời đó ở sông Dương Tử có một loại cá sấu nay đang ở trong tình trạng bị đe dọa tuyệt chủng. Để tránh sự tấn công của thủy quái, tộc Việt hay có tục lệ xâm mình. Bởi vậy tộc Việt ghép cho vật tổ của họ là Chim và Rồng với quan niệm song trùng lưỡng hợp (hai thành một). Còn tên thị tộc Hồng Bàng cũng từ vật tổ Chim Rồng mà ra. Văn hóa Lương Chử nằm ở hạ lưu sông Dương Tử trong khi đó nước Xích Quỷ của Kinh Dương Vương thì tới bắc Hồ Động Đình, đông thì Biển Đông, tây giáp với Ba Thục, nam tới nước Hồ Tôn (Chiêm Thành). Theo học giả Hà Văn Thùy thì ta thừa biết ranh giới quốc gia và ranh giới văn hóa chỉ tương đối mà thôi vì hay thường có sự chồng lấn lên nhau.

Lý do gì mà văn hoá Lương Chử lại biến mất và được thay sau đó bởi văn hóa Thạch Gia Hà (Shijiahé). Văn hóa nầy được xem thừa kế của văn hoá Khuất Gia Lĩnh (Qujialing (3400-2500 TCN) phát triển ở mức độ cao hơn qua các đồ bằng ngọc hình tròn tượng trưng cho trời như rồng hay chim phượng hoàng và được tập trung chung quanh khu vực Động Đình Hồ. Như vậy ta thấy rõ hơn nước Xích Quỷ của tộc Việt bao gồm các khu vực của hai nền văn hóa Lương Chử và Thạch Gia Hà. Tại sao gọi nước ta là Xích Quỷ? Thuật ngữ Xích 赤 được dùng để chỉ màu đỏ và ngụ ý chỉ phương nam. Còn Quỷ thì nói đến ngôi sao đỏ Yugui Qui, một chòm sao rực rỡ trong Nhị thập bát tú theo cách chia trong thiên văn học phương Đông.

Sự sụp đổ của nền văn hóa Lương Chử đã gây ra rất nhiều tranh cãi trong cộng đồng khảo cổ học. Một giả thuyết được phổ biến mạnh mẽ là thiên tai lũ lụt khiến tàn phá nhà cửa ở vùng đất nầy suốt một thời gian dài và buộc lòng cư dân ở đây phải di cư ẩn trốn ơ ở nơi khác. Họ đem đi với họ ngọc bích, nghề trồng lúa, nuôi tầm và sơn mài. Cũng có thể là đúng vì theo truyền thuyết Tam Hoàng Ngũ Đế của Trung Hoa thì Đại Vũ (vua đầu tiên của nhà Hạ) có công trị thủy để ổn định cuộc sống và phát triển việc cày cấy nên được vua Thuấn truyền ngôi lập ra nhà Hạ (2255 TCN – 2207 TCN) lúc mà văn hoá Lương Chử biến mất. Nhưng cũng khó tin nỗi vì đây là truyền thuyết được ghi chú lại trong sử ký của Tư Mã Thiên ở thời Tây Hán và cũng chưa có gì chứng minh xác thực nhà Hạ có thật hay không? Nhưng gần đây, giả thuyết nầy được nhà địa chất học người Áo, Christophe Spötl [7] của đại học Innsbruck cùng các đồng nghiệp xác nhận trong tạp chí Science Advances qua một nghiên cứu ngày 24 tháng 11 2021. Sự sụp đổ của văn hoá Lương Chử và các nền văn hóa ở thời kỳ đồ đá mới khác ở vùng hạ lưu sông Dương Tử là do sự biến đổi khí hậu, mưa lũ không ngừng khiến cư dân ở đây phải bỏ trốn ra đi.

Nhưng theo nhà nghiên cứu Nhật Bản Shin’ichi Nakamura [8] của đại học Kanazawa thì văn hóa Lương Chử biến mất vì sự cạn kiệt tài nguyên ngọc bích. Đối với văn hóa Lương Chử, toàn bộ nguồn sức mạnh chính trị đều dựa trên ngọc bích. Chỉ có những người sở hữu những thứ này mới có thể nắm giữ được quyền lực và tính hợp pháp của nó. Bởi vậy ở giai đoạn cuối cùng của nền văn hóa Lương Chử thì thấy các hiện vật như cong ngọc không còn được xuyên suốt nửa. Ngược lại ở trung lưu sông Dương Tử thì văn hóa Thạch Gia Hà (Shijiahe) được có kỷ thuật điêu khắc ngọc ở mức độ hoàn hảo và vượt trội hơn hai nền văn hoá Lương Chử và Hồng sơn qua 250 di chỉ bằng ngọc bích được các nhà khảo cổ tìm thấy ở địa điểm Tanjialing (Hồ Bắc) vào năm 2015. Văn hóa nầy trở thành một nơi trung tâm có tầm quan trọng hơn với sự thành hình của đại tộc Bách Việt (百越).

Tương tự thành phố Lương Chử, thành phố Thạch Gia Hà có một hệ thống kênh mương được đào xung quanh các khu đô thị và kết nối với các con sông gần đó. Trong số các hiện vật được tìm thấy ở văn hóa nầy ngoài đĩa bi, ngọc tông và rìu còn có một hiện vật cần có sự chú ý của mọi người đó là chiếc bình gốm lại có hình một thủ lỉnh mà trên đầu có cái gù trang sức với lông chim rất phù hợp với hình người nhảy múa mặc bộ đồ bằng lông chim trên các trống đồng (Ngọc Lũ chẳng hạn) của nền văn hoá Đồng Sơn. Cũng chính là biểu tượng của tộc Việt. Trong văn hóa Thạch Gia Hà còn thấy các hiện vật hình tròn bằng ngọc thể hiện chim phượng hoàng hay rồng được tạo tác một cách tinh vi. Theo nhà khoa học chính trị người Mỹ Charles E. Merriam của đại học Chicago thì đây là một phương pháp thực nghiệm quyền lực và đóng giữ vai trò «miranda» để buộc dân chúng phải kính trọng hai loại vật linh thiêng nầy [9]. Bởi vậy cư dân ở đây thích xâm hình rồng trên người và đội mũ lông chim để thể hiện điều nầy. Tâp tục xâm mình nầy dân tộc ta chỉ bỏ đi dưới thời vua Trần Anh Tôn. Văn hóa Thạch Gia Hà nằm ở trong địa bàn của nước Văn Lang tộc Việt. Qua sự mô tả địa lý trong truyền thuyết thì được biết nước Văn Lang thời đó đóng đô ở Phong Châu, có đất đai rộng lớn giáp ranh bắc đến hồ Động Đình, nam giáp nước Hồ Tôn (Chiêm Thành), đông giáp biển Nam Hải, tây đến Ba Thục (Tứ Xuyên). Tên Văn Lang có nguồn gốc từ tiếng Việt cổ là Blang hay Klang mà các dân tộc miền núi thường dùng để ám chỉ vật tổ, có thể đây là một loài chim nước thuộc họ chim Diệc. Có thể xem thời đó nước Văn Lang như một liên bang của các cộng đồng tộc Việt. Đây cũng là nhà nước đầu tiên của tộc Việt theo truyền thuyết trong lịch sử Việt Nam.

(miranda: danh từ dùng nói đến những biểu tượng gắn liền với cảm xúc của một dân tộc nhằm thể hiện sự tôn trọng và ngạc nhiên đối với họ.)

Bình rượu bằng đồng

Bình rượu bằng đồng

Theo truyền thuyết Phù Đổng Thiên Vương (hay Thánh Gióng) thì có một cuộc xung đột xảy ra giữa nước Văn Lang và nhà Thương dưới thời vua Hùng vương thứ VI. Trong Kinh Dịch được dịch bởi giáo sư Bùi Văn Nguyên thì tác giả có nói đến một cuộc viễn chinh quân sự được thực hiện trong vòng ba năm bởi vua hiếu chiến của nhà Thương tên là Wuding (Vũ Định) ở lãnh thổ của Ðộng Ðình Hồ (Kinh Châu) chống lại các dân du mục, thường gọi là « Quỷ ». Bởi vậy nước Văn Lang không có thiết lập bất kỳ mối quan hệ thương mại nào với nhà Thương cả. Những khám phá về các đồ vật bằng đồng ở Ninh Hương (Hồ Nam) vào những năm 1960 đã dẫn chứng cho ta thấy trong các chiến lợi phẩm được mang về trong cuộc viễn chinh ở phía nam Trung Quốc nầy thì có sự hiện diện một chiếc bình rượu bằng đồng được trang trí với khuôn mặt hình người Melanesian mà không có sự giải thích nào cả. Còn ở những nơi khác cùng thời thì có sự thành hình các nền văn hóa Nhị Lý Đầu của nhà Hạ ở Hà nam (Erlitou, Henan) hay của nhà Ân-Thương ở thung lũng sông Hoàng Hà thì thấy được có sự ảnh hưởng của các nền văn hoá Lương Chử và Thạch Gia Hà nầy ít nhiều qua các mẫu hình thao thiết tượng trưng cho khuôn mặt động vật (Taotie) hay phượng rồng.

Theo truyền thuyết Phù Đổng Thiên Vương (hay Thánh Gióng) thì có một cuộc xung đột xảy ra giữa nước Văn Lang và nhà Thương dưới thời vua Hùng vương thứ VI. Trong Kinh Dịch được dịch bởi giáo sư Bùi Văn Nguyên thì tác giả có nói đến một cuộc viễn chinh quân sự được thực hiện trong vòng ba năm bởi vua hiếu chiến của nhà Thương tên là Wuding (Vũ Định) ở lãnh thổ của Ðộng Ðình Hồ (Kinh Châu) chống lại các dân du mục, thường gọi là « Quỷ ». Bởi vậy nước Văn Lang không có thiết lập bất kỳ mối quan hệ thương mại nào với nhà Thương cả. Những khám phá về các đồ vật bằng đồng ở Ninh Hương (Hồ Nam) vào những năm 1960 đã dẫn chứng cho ta thấy trong các chiến lợi phẩm được mang về trong cuộc viễn chinh ở phía nam Trung Quốc nầy thì có sự hiện diện một chiếc bình rượu bằng đồng được trang trí với khuôn mặt hình người Melanesian mà không có sự giải thích nào cả. Còn ở những nơi khác cùng thời thì có sự thành hình các nền văn hóa Nhị Lý Đầu của nhà Hạ ở Hà nam (Erlitou, Henan) hay của nhà Ân-Thương ở thung lũng sông Hoàng Hà thì thấy được có sự ảnh hưởng của các nền văn hoá Lương Chử và Thạch Gia Hà nầy ít nhiều qua các mẫu hình thao thiết tượng trưng cho khuôn mặt động vật (Taotie) hay phượng rồng.

Đến thời điểm 2000 TCN thì có hạn hán ở vùng trung lưu của sông Dương Tử qua các cuộc nghiên cứu khảo cổ và khí tượng khiến làm cư dân ở Thạch Gia Hà cũng noi gót cư dân Lương Chử phải di tản vì không còn tiếp tục hoạt động trồng lúa được nửa. Dựa trên các nghiên cứu gen của Hugh McColl và các đồng nghiệp thì cư dân nông nghiệp ngữ hệ Nam Á nầy lại quay trở về lại Đông Nam Á cách đây 2000 năm TCN và hoà hợp một số ít với dân cư bản xứ sống nghề hái lượm và săn bắn. Liên bang của các tộc Việt ở sông Dương Tử cũng bị tan rã [10]. Sự việc nầy làm biến mất đi hai nền văn hóa Lương Chử và Thạch Gia Hà. Có thể xem sự tan rã nầy nó rất phù hợp với truyền thuyết Lạc Long Quân Âu Cơ lúc chia tay: 50 đứa con theo cha đi xuống đồng bằng (Lạc Việt), 50 đứa con theo mẹ Âu Cơ lên núi (Âu Việt hay Tây Âu). Được cai trị bởi các Hùng Vương, nước Văn Lang cũng bị thu hẹp lại sau đó với 15 bộ lạc từ 1879 TCN.

Có một điều đáng làm ta chú ý đến là ở văn hoá Thạch Gia Hà nầy có một hiện vật được gọi là nha chương mà nó có ý nghĩa là cái răng bằng ngọc dùng để tế núi sông và được phát hiện sớm nhất từ văn hóa Đại Vấn Khẩu (4100 -2600 TCN)(Dawenkou) ở khu vực tỉnh Sơn Đông (Shandong) mà được các nhà khảo cổ công nhận hiện nay. Nha chương (lame de jade) nầy được tìm thấy ở các ngôi mộ của các người có quyền lực và cấp bậc cao ở trong xã hội. Riêng ở Việt Nam hiện nay tìm được 8 nha chương ở Phùng Nguyên và Xóm Rền (tỉnh Phú Thọ, Việt Nam) có niên đại vào khoảng 1700-1400 TCN tức là thuộc về văn hóa Phùng Nguyên của dân tộc ta mà giáo sư Hà văn Tấn chứng minh chính xác luôn có sự liên tục không bị phá vở với các nền văn hóa Đồng Đậu-Gò Mun[11] trước văn hóa Đồng Sơn qua các niên đại carbon phóng xạ và tương ứng với thời kỳ của các vua Hùng (Hồng Bàng). Như vậy các nha chương nầy nó có phải đến từ văn hóa Thạch Gia Hà ở sông Dương Tử, trên dòng di cư của tộc Việt quay về lại Đông Nam Á (Vietnam) cách đây 4000 năm trước qua cuộc nghiên cứu nhân chủng học của nhà nghiên cứu Hirofumi Matsumura cùng các đồng nghiệp vào năm 2019 hay không [12] hay các hiện vật nầy là đến từ văn hoá Tam Tinh Đôi ở Tứ Xuyên (Sichuan)?

Chắc chắn là không đến từ văn hoá Tam Tinh Đôi ở Tứ Xuyên vì văn hoá nầy chỉ có niên đại vào khoảng 1200 TCN tức là sau văn hoá Phùng Nguyên có đến khoảng 500 năm. Như vậy nha chương Phùng Nguyên phải có nguồn gốc từ vùng Dương Tử với văn hóa Thạch Gia Hà. Nha chương được sử dụng như một dụng cụ lễ khí trong các dịp tế lễ được tìm thấy ở văn hoá Tam Tinh Đôi (Tứ Xuyên) hay dùng với chức năng đại diện quyền lực ở giai đọan đầu của thời Hùng Vương? Một câu hỏi chưa có phần giải đáp chính xác. Nhưng dù sao đi nửa chúng ta cũng tự hào là con Rồng cháu Tiên vì chính nhờ các truyền thuyết mà ông cha ta khéo léo dựng ra để ta tìm lại được chính xác cội nguồn qua các cuộc nghiên cứu di truyền và các cuộc khai quât khảo cổ trong thời gian qua.

Version française

Pourquoi le peuple vietnamien a-t-il plus de contes et de légendes que tout autre peuple d’Asie du Sud-Est ? Parfois, le lecteur se demande si ces légendes sont vraies ou non ou bien écrites par l’imagination humaine, quelque peu « magique » et irréelle. En fait, l’origine du peuple vietnamien est volontairement vague dans l’histoire car elle ne repose que sur ces légendes qui la rendent parfois difficile à croire et absurde comme la légende du « Lạc Long Quân- Âu Cơ » avec un sac qui a fait éclore une centaine d’œufs.

Pour le chercheur Paul Pozner [1], l’historiographie vietnamienne s’appuie sur une tradition historique longue et éternelle et s’exprime par une tradition orale se répétant sur plusieurs siècles du premier millénaire avant J.-C. sous la forme de légendes historiques qui se sont diffusées dans les temples ancestraux. Pourquoi notre nation n’a-t-elle pas de recueils d’histoire comme les Hans (les Chinois) malgré notre longue présence en Asie du Sud-Est ? Ce lieu est également considéré comme le berceau de la civilisation humaine à travers les commentaires du physicien britannique Stephen Oppenheimer dans l’ouvrage « Paradis à l’Est » [2]. C’est aussi dans notre pays que l’archéologue française Madeleine Colani a découvert, lors des fouilles archéologiques au début du 20ème siècle, la culture de Hoà Bình (18000-10000 avant JC) en 1922. C’est aussi la culture donnant naissance à la civilisation des Proto-Vietnamiens, une civilisation du riz inondé. La raison pour laquelle notre peuple n’a pas de recueil d’histoires est due à la domination chinoise durant presque mille ans. Ils ont toujours délibérément effacé l’origine de notre peuple à partir de la dynastie des Han de l’Ouest avec l’empereur Wudi.

Les mémoires historiques de Si Ma Qian [3] ont été toutes écrites avec l’intention politique et les ambitions de l’agresseur de siniser les peuples gouvernés et de renforcer le pouvoir et le prestige du fils du Ciel (empereur) dans un pays multi-ethnies et se conformer enfin à la signification de deux caractères chinois ((zhōngguó) (中華)(centre de l’univers). C’est pour cela que dans l’histoire de la Chine qu’il y a une incohérence visible dans de nombreux mythes. On est habitué à prendre l’habit de A pour recouvrir B en particulier à l’époque des Trois Augustes et Cinq Empereurs. Tout cela est dû en grande partie à l’emprunt de traditions, de coutumes et de figures mythologiques ou animales aux autres peuples que les Han ont réussi à siniser durant leur conquête. Les lettrés vietnamiens ont eu tort de s’appuyer sur les recueils d’histoire chinois comme le cas du livre intitulé « Đại Việt Sử Ký Toàn Thư » où les Giao Chỉ (les Proto-Vietnamiens) avaient besoin de l’aide du préfet chinois Ren Yan (Nhâm Diên) de Cửu Chân à l’époque des Han de l’Ouest pour savoir labourer la terre et cultiver le riz.

Il en va de même pour les archéologues occidentaux. En s’appuyant sur les livres chinois, ces derniers pensaient également que les Giao Chỉ (Jiaozhi) n’étaient que des gens vivant de la pêche, de la chasse et de la cueillette. Heureusement, grâce aux documents de recherche génétique de Hugh McColl et ses collègues [4] et aux fouilles archéologiques dans le passé, on sait maintenant que les habitants de Hoà Bình étaient les premiers à connaître la culture du riz irrigué et d’autres techniques agricoles comme la culture des céréales etc. (La cave des esprits par exemple). Puis il y a une grande inondation (un déluge) ayant eu lieu il y a 12.000 ans. Cela a fait s’enfoncer dans la mer une grande partie des terres habitées par des populations préhistoriques comme le bassin du Fleuve Rouge. Ces dernières étaient obligées de le quitter et de s’enfuir en se réfugiant partout dans le monde: à l’est dans l’océan Pacifique, à l’ouest en Inde ou au nord dans la région du fleuve Yang Tsé en emmenant avec elles les objets caractéristiques de la culture Hoà Binh trouvés dans le site Xian Ren Dong (Tiên Nhân động) de la province Jiangxi (Giang Tây) par exemple.

D’après les travaux de recherche génétique, il s’agit bien d’anciens habitants de l’Asie du Sud-Est (ou les gens de Hoà Bình) faisant leur arrêt dans le bassin du fleuve Yangtze car cet endroit était propice à l’époque au développement de la riziculture irriguée. Mais il y a encore un autre groupe de personnes qui aimaient à continuer leur migration vers l’Asie de l’Est en emmenant leur riz domestiqué (site de Shangshan, Thượng Sơn) et leur millet et en empruntant le passage à Zhejiang (Chiết Giang) pour s’installer non seulement dans le delta du Fleuve Jaune mais aussi jusqu’à la région du Fleuve Liao dans la Mongolie intérieure de la Chine d’aujourd’hui (Liêu Hà, Nội Mông Trung Hoa). C’est dans cette dernière qu’ils s’étaient unis aux autochtones nomades de l’Asie du Nord dont les vestiges étaient trouvés dans la grotte de la Porte du Diable sur le territoire russe limitrophe de la Corée (Sibérie occidentale) pour donner naissance à une race mongoloïde du Nord typique et une culture nommée « Hong Shan (Hồng Sơn) » découverte de la région de la Mongolie intérieure jusqu’à Liaoning. Ces Mongoloïdes du Nord étaient descendus dans la région du fleuve Jaune où vivaient les Hmongs qui étaient très doués en agriculture. Ils faisaient partie de la tribu Yi.

Étant à l’origine le dessin d’un homme 人 portant un arc 弓, ce caractère « Yi » 夷 nous donne une idée précise sur la particularité de ces gens du Nord. Ils se distinguaient par le tir à l’arc et ils étaient très habiles au combat. C’est pourquoi ils réussirent à gagner les victoires contre les Hmong dirigés par leur leader Chiyou (Xi Vưu) à Zhuolu (Trác Lộc) en l’an 2704 B.C. dans la province Hebei (Hà Bắc) et Shennong (Thần Nông) trois fois de suite, ce qui donna naissance ensuite à la civilisation chinoise (Yangshao (Ngưỡng Thiều) et Dawenkou (Đại Vấn Khẩu) et à la nouvelle race mongoloïde du Sud avec les anciens habitants de l’Asie du Sud Est. Étant de plus en plus nombreux, ces nouveaux mongoloïdes du Sud devenaient ainsi les sujets du bassin du fleuve Jaune et les ancêtres des Chinois d’aujourd’hui.

Dans le bassin du fleuve Yang Tsé, la formation de la communauté ethnique Yue-Tai-Kadai avait lieu du fait de la proximité des habitants autochtones de la famille linguistique austro-asiatique et des Pré-Austronésiens -Tai-Kadai venus plus tard. Compte-tenu des facteurs génétiques dus à la fusion des autochtones et des nouveaux venus issus des vagues de migration de l’Asie du Nord vers l’Asie du Sud et vice versa sur des milliers d’années, il y a eu des modifications dans la structure des gènes, notamment sous l’influence de l’environnement, cela a provoqué une changement naturel de la taille et de la couleur de la peau et a conduit à la formation des Mongoloïdes du Nord et du Sud et des Yue de la famille austro-asiatique. Celle-ci est constituée de plusieurs ethnies dans l’Asie de l’Est. C’est ici que les Yue se rendaient compte qu’ils étaient clairement différents des tribus nomades de la région du fleuve Jaune. Ils se disaient Yue (越). Le mot « Yue (hache) » qu’ils utilisaient pour se désigner eux-mêmes en tant que les gens vivant dans la région du fleuve Yang Tsé ou ayant l’habitude d’utiliser la hache pour cultiver les céréales et se défendre lorsqu’il y avait l’invasion des gens du Nord (les Chinois).

Ceux-ci les considéraient toujours comme des Man Di (des Sauvages). Pourtant ce sont eux qui ont conduit à la formation des grandes civilisations comme Liangzhu et Shijìahé. C’est grâce aux fouilles archéologiques entamées dans le cours inférieur du fleuve Yangtsé dans les années 1970 que l’on connaît la culture de Liangzhu. Celle-ci était bien plus avancée que la culture de Yang Shao puisqu’elle remonta à 3300 ans avant J.C. avec la découverte des pictogrammes sculptés sur la pierre, les plastrons de tortue, les os des animaux dans les séances de divination et des offices religieux. Ces dessins figuratifs étaient antérieurs de plus de 2 000 ans aux inscriptions oraculaires des Shang. On sait que les habitants de Liangzhu avaient un mode de vie sédentaire stable avec un système d’irrigation avec de l’eau emmagasinée par des canaux et une organisation sociale nécessitant beaucoup de main-d’œuvre pour la production et la distribution. Selon les documents archéologiques et la légende du roi Shennong (ayant eu vécu vers 3320-3080), il y a une coïncidence parfaite avec la culture de Liangzhu).

Le roi Shennong était le premier roi du Sud tandis que dans le Nord les tribus nomades étaient gouvernées par l’empereur jaune des Chinois Huang Di. Selon l’érudit vietnamien Hà Văn Thùy, les travaux scientifiques ont confirmé, à partir des preuves ADN effectuées directement sur les restes des habitants de Liangzhu, la présence de deux halo-groupes génétiques M122 (souche indonésienne) et M119 (souche mélanésienne). Ces deux races sont principalement des personnes originaires d’Asie du Sud-Est qui ont émigré en Chine il y a 12 000 ans. Ces deux races constituent la population de Liangzhu. Les artefacts les plus caractéristiques de la culture Lianzhu sont les disques en jade avec un trou circulaire au centre, les Cong dont le plus grand excavé pèse jusqu’à 3,5 kg et des objets de jade finement sculptés portant le caractère cérémoniel et présentés sous la forme d’un taotie ou d’une hache. Les socs en pierre ont des tailles beaucoup plus grandes, jusqu’à 60 cm de long dans certains cas. Les charrues sont certainement tirées par des animaux domestiques (éventuellement des buffles). La faucille, l’outil utilisé pour la récolte, est également d’une utilité considérable.

Cette culture a une hiérarchie sociale qui se reflète par les différences d’inhumation dans les tombes des gens détenant le pouvoir, des aristocrates et des pauvres. Dans les tombes des aristocrates, les objets utilitaires sont en jade, ivoire, soie ou laque tandis que dans le milieu pauvre, on ne trouve que des objets en céramique. Les disques bi sont employés dans le cadre d’un rituel et ont le rôle de protéger les trépassés dans le monde des morts. Le disque bi est souvent associé au Ciel et a la couleur verte tandis que le Cong dont la forme est tubulaire à l’extérieur et cylindrique à l’intérieur, est assimilé à la Terre et a la couleur jaune. Ce concept nous fait penser à la forme du gâteau de riz gluant à l’occasion de notre nouvel an (Tết). De plus, sur les objets de masque taotie on voit souvent l’emblème du dieu Chiyou faisant preuve de courage à travers son visage animalier d’après l’érudit Hà Văn Thùy [5].

Mais selon l’archéologue français Alain Thote, il s’agit bien d’un symbole ayant une valeur magico-religieuse liée à la mort lorsqu’il étudie les épées des anciens Yue (Wu-Yue) à l’époque des Zhou orientaux [6]. Bien que la distance dans le temps soit trop éloignée entre la culture de Liangzhu et la dynastie des Zhou orientaux au fil de nombreux siècles, la décoration du masque taotie sur les épées n’est pas fortuite. Elle est effectuée seulement sur une face tournée vers la lame. Cela implique certainement l’intercession et la protection d’une divinité, est ce le dieu Chiyou ? Après avoir été tué par Huang Di, Chiyou est devenu le dieu de la guerre et protège ainsi tous les groupes ethniques Yue vivant dans le sud de la Chine, y compris les gens de Liangzhu reconnus par les érudits chinois comme les adorateurs des oiseaux et des animaux Vũ Nhân ( 羽 人) ou Vũ Dân càd les Enfants du Dragon et les Grands Enfants de l’Immortelle (Con Rồng Cháu Tiên).

Selon le dictionnaire sino-vietnamien, le mot Vũ (羽) fait référence à un oiseau. Pourquoi Fée-Dragon ? Dans les temps anciens, les oiseaux sont des animaux pouvant voler au-dessus des montagnes jusqu’à l’endroit où vivent les Immortelles. Quant au dragon, il est certainement un monstre marin qui, dans l’histoire de notre pays, s’appelle le dragon d’eau (Giao Long). À cette époque, dans le fleuve Yang Tse, il y avait un type d’alligator qui est maintenant en danger d’extinction. Afin d’éviter l’attaque de ce monstre marin, les Proto-Vietnamiens avaient coutume de se tatouer. C’est pourquoi ils associaient à leur totem le couple (Oiseau /Dragon) avec la notion de dualité (deux en un). Le nom du clan Hồng Bàng provient également du couple (Oiseau/Dragon). La culture de Lianzhu est localisée dans le cours inférieur du fleuve Yang Tsé, tandis que le pays Xích Qủi de Kinh Dương Vương est délimité au nord par le lac Động Đình, à l’est par la mer de Hainan, à l’ouest par le royaume Ba Shu (Ba Thục) et au sud par le Champa (Hồ Tôn). Selon le chercheur Hà Văn Thùy, on sait bien que les frontières nationales et les frontières culturelles ne sont que relatives car elles se chevauchent souvent les unes sur les autres.

Pour quelle raison la culture de Liangzhu a-t-elle disparu pour être remplacée plus tard par la culture de Shijiahé ? Cette dernière a été considérée comme l’héritière de la culture de Qujialing (3400-2500 av. J.-C.). Elle s’est développée aussi à un niveau supérieur à travers des objets ronds en jade représentant le ciel comme les dragons ou les phénix et s’est concentrée communément autour du lac. On voit donc plus clairement que le pays de Xich Gui du peuple vietnamien englobe les zones de deux cultures de Liangzhu et de Shijiahé. Pourquoi notre pays s’appelle-t-il Xích Quỷ? Xích désigne la couleur rouge et fait allusion au sud, tandis que le terme Quỷ fait référence à l’étoile brillante de couleur rouge Yugui Qui parmi les 28 loges nocturnes stellaires organisées dans un système de subdivision du ciel utilisé dans l’astronomie orientale.

L’effondrement de la culture de Liangzhu a suscité de nombreuses controverses et de débats dans la communauté des archéologues. On retient la thèse la plus répandue selon laquelle les catastrophes naturelles ont provoqué des inondations dévastant ainsi les habitations de cette région pendant longtemps et forçant les habitants d’ici à migrer et à se cacher ailleurs. Ils ont emporté avec eux le jade, la riziculture, l’élevage des vers à soie et la laque. C’est peut-être vrai car selon la légende des Trois Augustes et des Cinq Empereurs de Chine, You le Grand (le premier monarque de la dynastie des Xia) avait le mérite d’inventer les techniques d’irrigation pour maîtriser les fleuves, stabiliser la vie de ses habitants et développer l’agriculture. C’est pour cela que l’empereur Shun (vua Thuấn) lui céda le trône pour fonder la dynastie des Xia (2255 avant JC – 2207 avant JC) lors de la disparition de la culture Liangzhu. Mais c’est difficile d’accepter aussi cette version car il s’agit bien d’une légende recopiée dans les mémoires historiques de Sima Qian sous la dynastie des Han occidentaux et rien n’apporte la preuve de l’existence de la dynastie des Xia. Mais récemment, cette hypothèse a été confirmée par le géologue autrichien Christophe Spötl [7] de l’université d’Innsbruck et ses collègues dans la revue « Science Advances» au travers d’une étude datée du 24 novembre 2021. L’effondrement de la culture Liangzhu et d’autres cultures néolithiques dans la région du cours inférieur du fleuve Yang Tsé ont été dues au changement climatique, aux pluies incessantes et aux inondations incitant les habitants à fuir.

Mais selon le chercheur japonais Shin’ichi Nakamura [8] de l’université de Kanazawa, la culture Liangzhu a disparu à cause de l’épuisement des ressources en jade. Pour la culture Liangzhu, toute la source du pouvoir politique était basée sur le jade. Seuls ceux qui possèdent ces ressources peuvent détenir leur pouvoir et leur légitimité. À la dernière étape de la culture de Liangzhu, des artefacts en jade comme les Cong ne sont plus translucides et contiennent des impuretés. En revanche, au milieu du fleuve Yang Tse, la culture Shijiahé possède une technique de sculpture de jade à un niveau de perfection supérieur à celui de deux cultures Liangzhu et Hongshan au travers de 250 objets en jade que les archéologues ont trouvés lors des fouilles sur le site de Tanjialing (Hubei) en 2015. Cette culture occupe désormais une grande place importante avec la formation des Cent Yue.

Dans la culture de Shijiahé, il y a également des artefacts ronds en jade (phénix, dragons) représentant le Ciel et fabriqués de manière tellement sophistiquée. Selon le politologue américain Charles E. Merriam de l’université de Chicago, il s’agit d’un moyen de légitimation empirique du pouvoir et de possession de la fonction «miranda» pour forcer les gens à respecter ces deux animaux sacrés.[9]. C’est pourquoi les gens d’ici aiment tatouer des dragons sur leur corps et porter des chapeaux de plumes pour les montrer. Cette coutume de tatouage n’a été abandonnée que sous le règne du roi Trần Anh Tôn.

un leader de Shijiahé

(miranda: se rapporte aux symboles liés à l’émotivité d’un peuple pour lui imposer le respect et l’émerveillement.)

La culture de Shijiahé est localisée dans l’aire du royaume des Proto-Vietnamiens Văn Lang. À travers la description géographique de la légende, on sait qu’à cette époque le royaume Văn Lang avait Phong Châu pour capitale. Il était délimité au nord par le lac Dongting (Hunan) (Động Đình, Hồ Nam), au sud par le Champa (Hồ Tôn), à l’est par la mer de Hainan et à l’ouest par le royaume Ba Shu (Sichuan). Le nom Văn Lang est dérivé de l’ancien mot Yue Blang ou Klang que les montagnards utilisent souvent pour désigner le totem, c’est peut-être un oiseau aquatique de la famille des hérons. Le royaume de Văn Lang peut être considéré à cette époque comme une fédération de communautés ethniques Yue. C’est aussi le premier état de l’ethnie Yue selon la légende de l’histoire vietnamienne.

Selon la légende du Seigneur Phù Đổng (ou Thánh Gióng), il y eut un conflit entre le royaume Văn Lang et la dynastie des Shang sous le roi Hùng Vương VI. Dans le Yi King traduit par le professeur Bùi Văn Nguyên, l’auteur mentionne une expédition militaire menée en trois ans par le roi guerrier de la dynastie des Shang nommé Wuding (Vũ Định) dans le territoire du lac Động Đình (Kinh Châu, Jīngzhōu ) contre les nomades souvent appelés « Diables ». Ce conflit pourrait expliquer la raison principale pour laquelle le royaume de Văn Lang n’a établi aucune relation commerciale avec les Shang. Les découvertes d’objets en bronze à Ningxiang (Hunan) dans les années 1960 ont montré que dans le butin ramené lors de cette expédition dans le sud de la Chine, il y avait la présence d’un vase à vin en bronze orné d’un visage humain mélanésien sans aucune explication.

un vase à vin en bronze

Dans d’autres endroits à la même époque, il y a la formation des cultures Erlitou de la dynastie des Xia dans le Henan ou de la dynastie des Shang dans la vallée du fleuve Jaune. L’influence de ces cultures Liangzhu et Shijiahé y est plus ou moins visible à travers les modèles ayant des visages d’animaux (Taotie) ou des animaux phénix et dragon. Au moyen des études archéologiques et météorologiques, on sait qu’en l’an 2000 avant J.C, il y avait une sécheresse dans la région moyenne du fleuve Yang Tsé, ce qui obligea les habitants de Shijiahé à suivre les traces des habitants de Liangzhu à évacuer la région car ils ne pouvaient plus continuer à faire la riziculture. Sur la base d’études génomiques de Hugh McColl et de ses collègues, cette population agraire austro-asiatique Yue était obligée de revenir en Asie du Sud-Est il y a 2 000 ans et d’effectuer la fusion en une infime partie avec la population indigène vivant sur place de la cueillette et de la chasse. L’union des tribus Yue du fleuve Yang Tsé a également été dissoute [10]. Cet incident a causé la disparition de deux cultures Liangzhu et Shijiahé. On voit que cette dissolution est très conforme à la légende du roi Lạc Long Quân et de la princesse Âu Cơ au moment de la séparation: 50 enfants ont suivi le père dans les plaines (Luo Yue) et 50 autres enfants ont accompagné la mère Âu Cơ dans les montagnes (Si Ngeou). Dirigé par les rois Hùng, le royaume Văn Lang se rétrécit plus tard avec ses 15 tribus à partir de 1879 av. J.C.

Une chose à laquelle il convient de prêter attention est que dans cette culture Shijiahé, il existe un artefact appelé nha chương (ou une dent de jade) utilisée pour faire des offrandes aux montagnes et aux rivières et reconnue et attribuée jusque-là à la culture Dawenkou (Đại Vấn Khẩu) dans la région de la province du Shandong (Shandong) par les archéologues. Cette lame de jade se trouve dans les tombes des personnes détentrices du pouvoir et de haut rang dans la société. Particulièrement au Vietnam, il y a actuellement 8 lames trouvées à Phùng Nguyên et Xóm Rèn (province de Phú Thọ, Vietnam) datant d’environ 1700-1400 avant J.C. Cela signifie qu’elles appartiennent à la culture Phùng Nguyên de notre peuple. Le professeur Hà Văn Tấn a prouvé avec précision qu’il existe toujours la continuité ininterrompue de cette culture avec celles de Đồng Dậu et Gò Mun[11] qui sont antérieures à la culture Đồng Sơn au moyen des datations au radiocarbone et qu’il correspond ainsi à la période des rois Hùng (Hồng Bàng). Ces lames de jade doivent donc provenir de la culture Shijiahé du fleuve Yang Tsé lors de la migration des Proto-Vietnamiens vers l’Asie du Sud-Est (Vietnam) il y a 4000 ans rapportée par l’étude anthropologique du chercheur Hirofumi Matsumura et ses collègues en 2019 [12] ou elles sont issues de la culture Sanxingdui de Sichuan ?

Certainement elles ne viennent pas de la culture Sanxingdui au Sichuan car cette dernière ne date que d’environ 1200 avant J.C., soit environ 500 ans de décalage avec la culture Phùng Nguyên. Ainsi, la lame de jade de Phùng Nguyên doit provenir de la région du Yang Tse avec la culture Shijiahé. La lame de jade est utilisée comme un outil rituel dans les occasions cérémonielles de la culture Sanxingdui (Sichuan) ou comme un objet du pouvoir au début de la période des rois Hùng? C’est une question dont on n’a pas encore la réponse juste. Mais quoi qu’il en soit, nous sommes toujours fiers d’être les descendants du Dragon et les Grands Enfants de l’Immortelle car grâce aux légendes que nos ancêtres ont savamment inventées et aux études génétiques et aux fouilles archéologiques dans un passé récent nous réussissons à retrouver notre origine avec exactitude.

(Miranda se rapporte aux symboles s’adressant à l’« émotivité » d’un peuple pour lui imposer le respect ou l’émerveillement).

Paris le 28/02/2023

English version

Why does the Vietnamese people have more tales and legends than any other people in Southeast Asia? Sometimes, the reader wonders whether these legends are true or not, or if they were written by human imagination, somewhat « magical » and unreal. In fact, the origin of the Vietnamese people is deliberately vague in history because it relies solely on these legends, which sometimes make it difficult to believe and absurd, like the legend of « Lạc Long Quân – Âu Cơ » with a sack that hatched a hundred eggs. For researcher Paul Pozner [1], Vietnamese historiography is based on a long and eternal historical tradition and is expressed through an oral tradition repeated over several centuries of the first millennium BC in the form of historical legends that have spread in ancestral temples.

Why does our nation not have historical records like the Hans (the Chinese) despite our long presence in Southeast Asia? This place is also considered the cradle of human civilization according to the comments of British physicist Stephen Oppenheimer in the book « Paradise in the East » [2]. It is also in our country that French archaeologist Madeleine Colani discovered, during archaeological excavations in the early 20th century, the Hoà Bình culture (18000-10000 BC) in 1922. This is also the culture that gave birth to the civilization of the Proto-Vietnamese, a civilization of wet rice cultivation. The reason why our people do not have historical records is due to Chinese domination for nearly a thousand years. They have always deliberately erased the origin of our people starting from the Western Han dynasty with Emperor Wudi.

The historical memoirs of Si Ma Qian [3] were all written with the political intention and ambitions of the aggressor to sinicize the governed peoples and to strengthen the power and prestige of the Son of Heaven (emperor) in a multi-ethnic country, ultimately conforming to the meaning of the two Chinese characters (zhōngguó) (中華) (center of the universe).

This is why in the history of China there is a visible inconsistency in many myths. We are accustomed to taking the garment of A to cover B, particularly in the era of the Three August Ones and Five Emperors. All this is largely due to the borrowing of traditions, customs, and mythological or animal figures from other peoples whom the Han succeeded in sinicizing during their conquest. Vietnamese scholars were wrong to rely on Chinese historical collections such as the book titled « Đại Việt Sử Ký Toàn Thư, » where the Giao Chỉ (the Proto-Vietnamese) needed the help of the Chinese prefect Ren Yan (Nhâm Diên) of Cửu Chân during the Western Han period to learn how to plow the land and cultivate rice.

The same goes for Western archaeologists. Relying on Chinese books, they also thought that the Giao Chỉ were merely people living by fishing, hunting, and gathering. Fortunately, thanks to the genetic research documents by Hugh McColl and his colleagues [4] and past archaeological excavations, it is now known that the inhabitants of Hoà Bình were the first to be familiar with irrigated rice culture and other agricultural techniques such as cereal cultivation, etc. (The Spirit Cave, for example). Then there was a great flood (a deluge) that occurred 12,000 years ago. This caused a large part of the lands inhabited by prehistoric populations, such as the Red River basin, to sink into the sea. These populations were forced to leave and flee, seeking refuge all over the world: eastward into the Pacific Ocean, westward into India, or northward to the Yangtze River region, bringing with them characteristic objects of the Hoà Bình culture found at the Xian Ren Dong (Tiên Nhân Cave) site in Jiangxi province, for example.

According to genetic research, these are indeed ancient inhabitants of Southeast Asia (or the Hoà Bình people) who made a stop in the Yangtze River basin because this area was favorable at the time for the development of irrigated rice cultivation. But there is also another group of people who preferred to continue their migration towards East Asia, bringing their domesticated rice (Shangshan site, Thượng Sơn) and millet, and passing through Zhejiang to settle not only in the Yellow River delta but also in the Liao River region in today’s Inner Mongolia, China. It is in this latter area that they united with the indigenous nomads of Northern Asia, whose remains were found in the Devil’s Gate cave on Russian territory bordering Korea (Western Siberia), giving rise to a typical Northern Mongoloid race and a nomadic culture called « Hong Shan, » discovered from the Inner Mongolia region to Liaoning. These Northern Mongoloids had descended into the Yellow River region where the Hmongs, who were very skilled in agriculture, lived. They were part of the Yi tribe.

Originally being the drawing of a man 人 carrying a bow 弓, this character « Yi » 夷 gives us a clear idea about the particularity of these Northern people. They were distinguished by archery and were very skilled in combat. That is why they succeeded in winning victories against the Hmong led by their leader Chiyou (Xi Vưu) at Zhuolu (Trác Lộc) in the year 2704 B.C. in Hebei province (Hà Bắc) and Shennong (Thần Nông) three times in a row, which then gave birth to Chinese civilization (Yangshao (Ngưỡng Thiều) and Dawenkou (Đại Vấn Khẩu)) and to the new southern Mongoloid race together with the ancient inhabitants of Southeast Asia. Becoming increasingly numerous, these new southern Mongoloids thus became the subjects of the Yellow River basin and the ancestors of today’s Chinese.

In the Yangtze River basin, the formation of the Yue-Tai-Kadai ethnic community took place due to the proximity of the indigenous inhabitants of the Austro-Asiatic language family and the Pre-Austronesian Tai-Kadai who arrived later. Considering the genetic factors resulting from the fusion of the indigenous people and the newcomers from waves of migration from North Asia to South Asia and vice versa over thousands of years, there were changes in the gene structure, notably under the influence of the environment. This caused a natural change in size and skin color and led to the formation of the Northern and Southern Mongoloids and the Yue of the Austro-Asiatic family. This family consists of several ethnic groups in East Asia. It was here that the Yue realized they were clearly different from the nomadic tribes of the Yellow River region. They called themselves Yue. The word « Yue (axe) » they used to designate themselves referred to the people living in the Yangtze River region or those accustomed to using the axe to cultivate cereals and defend themselves when there was an invasion by people from the North (the Chinese).

They always considered them as Man Di (Savages). Yet it was they who led to the formation of great civilizations such as Liangzhu and Shijahe. It is thanks to the archaeological excavations started in the lower course of the Yangtze River in the 1970s that the Liangzhu culture became known. This culture was much more advanced than the Yangshao culture since it dates back to 3300 BC with the discovery of pictograms carved on stone, turtle plastrons, animal bones used in divination sessions and religious ceremonies. These figurative drawings were more than 2,000 years older than the oracle inscriptions of the Shang. It is known that the inhabitants of Liangzhu had a stable sedentary lifestyle with an irrigation system using water stored by canals and a social organization requiring a lot of labor for production and distribution. According to archaeological documents and the legend of Shennong (who is said to have lived around 3320-3080 BC), there is a coincidence with the Liangzhu culture.

King Shennong was the first king of the South, while in the North, nomadic tribes were governed by the Yellow Emperor of the Chinese, Huang Di. According to the Vietnamese scholar Hà Văn Thùy, scientific studies have confirmed, based on DNA evidence taken directly from the remains of the inhabitants of Lianzhu, the presence of two genetic haplogroups M122 (Indonesian strain) and M119 (Melanesian strain). These two races are mainly people originating from Southeast Asia who migrated to China 12,000 years ago. These two races make up the population of Lianzhu. The most characteristic artifacts of the Lianzhu culture are jade discs with a circular hole in the center, Cong (cylindrical tubes) with the largest excavated weighing up to 3.5 kg, and finely carved jade objects bearing ceremonial characters and present in the form of a taotie or an axe. The stone plowshares are much larger in size, up to 60 cm long in some cases. The plows were certainly pulled by domesticated animals (possibly buffalo). The sickle, the tool used for harvesting, was also of considerable use.

This culture has a social hierarchy that is reflected in the differences in burial practices in the graves of people holding power, aristocrats, and the poor. In the aristocrats’ graves, utilitarian objects are made of jade, ivory, silk, or lacquer, while in the poor environment, only ceramic objects are found. The bi discs are used as part of a ritual and serve to protect the deceased in the world of the dead. The bi disc is often associated with the Sky and is green in color, while the Cong, which is tubular on the outside and cylindrical on the inside, is associated with the Earth and is yellow in color. This concept reminds us of the shape of the sticky rice cake during our New Year (Tết). Moreover, on taotie mask objects, one often sees « the identity of a deity through its animal face, » which is the emblem of the god Chiyou, demonstrating courage according to the scholar Hà Văn Thùy [5].

But according to the French archaeologist Alain Thote, it is indeed a symbol with a magico-religious value related to death when he studies the swords of the ancient Yue (Wu-Yue) during the Eastern Zhou period [6]. Although the time gap is too great between the Lianzhu culture and the Eastern Zhou dynasty over many centuries, the decoration of the taotie mask on the swords is not accidental. It is made only on one side facing the blade. This certainly implies the intercession and protection of a deity, is it the god Chiyou? After being killed by Huang Di, Chiyou became the god of war and thus protects all Yue ethnic groups living in southern China, including the Liangzhu people recognized by Chinese scholars as the bird and animal worshippers Vũ Nhân (羽人) or Vũ Dân i.e. the Children of the Dragon and the Grandchildren of the Immortal (Con Rồng Cháu Tiên). According to the Sino-Vietnamese dictionary, the word Vũ (羽) refers to a bird. Why Fairy-Dragon? In ancient times, birds were animals capable of flying over mountains to the place where fairies live. As for the dragon, it is certainly a sea monster which, in the history of our country, is called the water dragon (Giao Long). At that time, in the Yangtze River, there was a type of alligator that is now endangered. To avoid attacks from this sea monster, the Proto-Vietnamese had the custom of tattooing themselves.

That is why they associated their totem with the couple (Bird/Dragon) and the notion of duality (two in one). The name of the Hồng Bàng clan also comes from the couple (Bird/Dragon). The culture of Lianzhou is located in the lower course of the Yangtze River, while the Xích Qủi country of Kinh Dương Vương is bounded to the north by Động Đình Lake, to the east by the East Sea, to the west by the Ba Thục kingdom, and to the south by Champa (Hồ Tôn). According to researcher Hà Văn Thùy, it is well known that national borders and cultural borders are only relative because they often overlap each other. For what reason did the culture of Lianzhou disappear to be later replaced by the culture of Shijiahé? The latter has been considered the heir of the Qujialing culture (3400-2500 B.C.). It also developed at a higher level through round jade objects (dragons, phoenixes) representing the sky and commonly concentrated around the lake. It is therefore clearer that the country of Xích Quỷ of the Vietnamese people encompasses the areas of two cultures: Lianzhou and Shijiahé.

Why is our country called Xích Quỷ? Xích denotes the color red and alludes to the south, while the term Quỷ refers to the bright red star Yugui Qui among the twenty-eight lunar mansions arranged in a system of sky subdivisions used in Eastern astronomy. The collapse of the Lianzhu culture has sparked numerous controversies and debates within the archaeological community. The most widely accepted theory holds that natural disasters caused floods that devastated the dwellings in this region for a long time, forcing the inhabitants to migrate and hide elsewhere. They took with them jade, rice cultivation, sericulture, and lacquer. This may be true because, according to the legend of the Three August Ones and Five Emperors of China, Yu the Great (the first monarch of the Xia dynasty) earned merit by inventing irrigation techniques to control the rivers, stabilize the lives of his people, and develop agriculture. For this reason, Emperor Shun (vua Thuấn) ceded the throne to him to found the Xia dynasty (2255 BC – 2207 BC) upon the disappearance of the Lianzhu culture.

On the other hand, in the middle of the Yangtze River, the Shijiahé culture possesses a jade carving technique at a level of perfection superior to that of the Liangzhu and Hongshan cultures, demonstrated through 250 jade objects that archaeologists found during excavations at the Tanjialing site (Hubei) in 2015. This culture now holds a significant place with the formation of the Hundred Yue.

Similar to the city of Liangzhu, the city of Shijiahé has a system of canals dug around urban areas and connected to nearby rivers. Among the artifacts found in this culture, besides the bi disks, jade Cong, and axes, there is one artifact that captures everyone’s attention. It is a ceramic vase with the image of a leader whose head is adorned with a headdress decorated with bird feathers, perfectly matching the dancing figure wearing a feather costume on the bronze drums of the Đông Sơn culture (Ngọc Lũ, for example). It is the symbol of the Yue people.

In the Shijiahe culture, there are also round jade artifacts (phoenix, dragons) representing the Sky and made in such a sophisticated manner. According to American political scientist Charles E. Merriam from the University of Chicago, this is an empirical means of legitimizing power and possessing the « miranda » function to force people to respect these two sacred animals.[9]. That is why the people here like to tattoo dragons on their bodies and wear feather hats to show it. This tattooing custom was only abandoned during the reign of King Trần Anh Tôn.

The Shijiahe culture is located in the area of the Proto-Vietnamese Văn Lang kingdom. Through the geographical description of the legend, it is known that at that time the Văn Lang kingdom had Phong Châu as its capital. It was bordered to the north by Dong Dinh Lake, to the south by Champa (Hồ Tôn), to the east by the sea of Hainan, and to the west by the Ba Shu kingdom (Sichuan).

The name Văn Lang is derived from the ancient word Yue Blang or Klang, which the mountaineers often use to designate the totem; it may be a water bird from the heron family. The kingdom of Văn Lang can be considered at that time as a federation of Yue ethnic communities. It is also the first state of the Yue ethnicity according to the legend of Vietnamese history. According to the legend of Lord Phù Đổng (or Thánh Gióng), there was a conflict between the Văn Lang kingdom and the Shang dynasty under King Hùng Vương VI. In the Yi King translated by Professor Bùi Văn Nguyên, the author mentions a military expedition carried out over three years by the warrior king of the Shang dynasty named Wuding (Vũ Định) in the territory of Động Đình Lake (Kinh Châu, Jīngzhōu) against the nomads often called « Devils« .

This conflict could explain the main reason why the kingdom of Văn Lang did not establish any commercial relations with the Shang. The discoveries of bronze objects in Ningxiang (Hunan) in the 1960s showed that among the loot brought back during this expedition to southern China, there was a bronze wine vessel adorned with a Melanesian human face without any explanation. In other places at the same time, there was the formation of the Erlitou culture of the Xia dynasty in Henan or the Shang dynasty in the Yellow River valley, the influence of these Liang Chu and Shijiahé cultures is more or less visible through patterns featuring animal faces (Taotie) or images of phoenixes and dragons.

Through archaeological and meteorological studies, it is known that in the year 2000 BC, there was a drought in the middle region of the Yangtze River, which forced the inhabitants of Shijiahe to follow in the footsteps of the inhabitants of Liangzhu and evacuate the area because they could no longer continue rice cultivation. Based on genomic studies by Hugh McColl and his colleagues, this Austro-Asian agrarian Yue population was forced to return to Southeast Asia 2,000 years ago and merge in a small part with the indigenous population living there who practiced gathering and hunting. The union of the Yue tribes of the Yangtze River was also dissolved [10]. This incident caused the disappearance of the Liangzhu and Shijiahe cultures. This dissolution closely aligns with the legend of King Lạc Long Quân and Princess Âu Cơ at the time of their separation: 50 children followed the father to the plains (Luo Yue) and 50 other children accompanied the mother Âu Cơ to the mountains (Si Ngeou).

Led by the Hung kings, the Văn Lang kingdom later shrank with its 15 tribes starting from 1879 BC. One thing to pay attention to is that in this Shijiahe culture, there is an artifact called nha chương (or a jade tooth) used to make offerings to mountains and rivers, which has so far been recognized and attributed by archaeologists to the Dawenkou culture in the Shandong province region. This jade blade is found in the tombs of people holding power and high rank in society. Particularly in Vietnam, there are currently 8 blades found at Phùng Nguyên and Xóm Rèn (Phú Thọ province, Vietnam) dating from around 1700-1400 BC. This means they belong to the Phùng Nguyên culture of our people. Professor Hà Văn Tân has accurately proven that there is still an uninterrupted continuity of this culture with those of Đồng Dậu and Gò Mun, which are earlier than the Đồng Sơn culture, through radiocarbon dating, and that it thus corresponds to the period of the Hùng kings (Hong Bang).

These jade blades must therefore come from the Shijiahe culture of the Yangtze River during the migration of the Proto-Vietnamese to Southeast Asia (Vietnam) 4000 years ago, as reported by the anthropological study of researcher Hirofumi Matsumura and his colleagues in 2019 [12], or do they originate from the Sangxindui culture of Sichuan? Certainly, they do not come from the Sanxingdui culture in Sichuan because the latter dates only to around 1200 BC, about 500 years later than the Phùng Nguyên culture. Thus, the jade blade of Phùng Nguyên must come from the Yangtze region with the Shijiahe culture. The jade blade is used as a ritual tool on ceremonial occasions in the Sangxindui culture (Sichuan) or as an object of power at the beginning of the Hùng kings’ period?

A question still does not have a correct answer. But in any case, we are always proud to be the « descendants of the Dragon and the Great Children of the Immortal » because, thanks to the legends that our ancestors skillfully invented and to genetic studies and archaeological excavations in the past, we manage to accurately trace our origin.

(miranda: refers to symbols related to the emotionality of a people to impose respect and wonder upon them.)

Bibliographie

[1] Paul Pozner: Le problème des chroniques vietnamiennes, origines et influences étrangères. BEFO, année 1980, vol 67, no 67, p275-302

[2] Stephen Oppenheimer: Địa đàng ở Phương Đông. Lịch sử huy hoàng của lục địa Đông Nam Á bị chìm ? NXB Lao Động; 2005.

[3] Edouard Chavannes: Mémoires historiques de Se-Ma Tsien de Chavannes, tome quatrième.

[4] Hugh McColl, Fernando Racimo, Lasse Vinner, et al. (2018). The prehistoric peopling of Southeast Asia. Science;361(6397) 88-92.

[5] Hà Văn Thùy: Phát hiện di vật văn hóa Lương Chữ tại Viêt Nam. Nghiên cứu lịch sử.

[6] Alain Thote: Note sur la postérité du masque de Liangzhu à l’époque des Zhou orientaux, Arts asiatiques. Tome 51, 1996. pp. 60-72.

[7] Christoph Spotl, Haiwei Zhang, and all (2021) Collapse of the Liangzhu and other Neolitic cultures in the lower Yantze region in response to climate change. Science Advances Vol 7, Issue 48.

[8] Shin’ichi Nakamura: Le riz, le jade et la ville. Évolution des sociétés néolithiques du Yangzi. Éditions de l’EHESS « Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales. 2005/5 60e année | pages 1009 à 1034.

[9] Charles E. Merriam, Political power : Its composition and incidence, New York-Londres, Whittlesey House/McGraw-Hil, 1934.

[10] Lang Linh: Lịch sử hình thành và tan rã của cộng đồng tộc Viêt. Lược sử tộc Việt.

[11] Hà văn Tấn: Theo dấu các văn hóa cổ. Nhà Xuất Bản Khoa Học Xã Hội. Hànội 1998.

[12] Hirofuma Matsumura, Hsiao-chun Hung, Charles Higham et al. (2019). Craniometrics reveal « Two Layers » of Prehistoric Human Dispersal in Eastern Eurasia. Scientifics reports; 9(1): 1451.

Dominique Lelièvre: La grande époque de Wudi. Editions You Feng. 2001

Bai Shouyi: Précis d’histoire de Chine. Editions en langues étrangères. Beijing, 1988

René Grousset: Histoire de la Chine. Des origines à la seconde guerre mondiale. France-Loisirs, Paris 1997

Norman Jerry- Mei tsulin 1976 The Austro asiatic in south China : some lexical evidence, Monumenta Serica 32 :274-301

Sun, Jin & Li, Yingxiang & Ma, Pengcheng & Yan, Shi & Cheng, Hui-Zhen & Fan, Zhi-Quan & Deng, Xiao-Hua & Ru, Kai & Wang, Chuan-Chao & Chen, Gang & Wei, Ryan. (2021). Shared paternal ancestry of Han, Tai-Kadai-speaking, and Austronesian-speaking populations as revealed by the high resolution phylogeny of O1a-M119 and distribution of its sub-lineages within China. American journal of physical anthropology. 174. 10.1002/ajpa.24240.

Corinne Debaine-Francfort : La redécouverte de la Chine ancienne. Editions Gallimard 1998.

Léonard Aurousseau: La première conquête chinoise des pays annamites (IIIe siècle avant notre ère). BEFO, année 1923, Vol 23, no 1.

Bình Nguyên Lộc: Lột trần Việt ngữ. Talawas.